Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

Easter Sunday, 2019

1 Corinthians 15:1-11

Resurrection Day! The most holy day in the Christian calendar as we celebrate the risen Christ! And what a glorious day we’re enjoying.

Today I begin a series on the resurrection, working through Paul’s final essay in 1st Corinthians? Some scholars divide 1st Corinthians into five essays.[1] Paul’s first essay, which consist of the first four chapters, focuses on the problem of divisions within the church. His answer is unity through the cross. So Paul begins this letter talking about the cross. His final essay is about the resurrection. Paul covers the bases in 1st Corinthians, from Good Friday to Easter Sunday.

The 15th chapter of 1st Corinthians provides the most detailed treatment of the resurrection found in scripture. In the gospels, we read first-hand accounts of Jesus’ resurrection. Here, Paul explores resurrection theology and its implication.

The focus of our faith is that Christ rose from the grave. Yes, it’s important that he paid the price for our sin on Friday. But if there is no resurrection, what difference would it make? The reason Friday can be called “Good Friday” and not “Black Friday” or “Sad Friday” or “We are Doomed Friday” is because Christ rose from the dead. And he promises the same to those who believe and follow him.

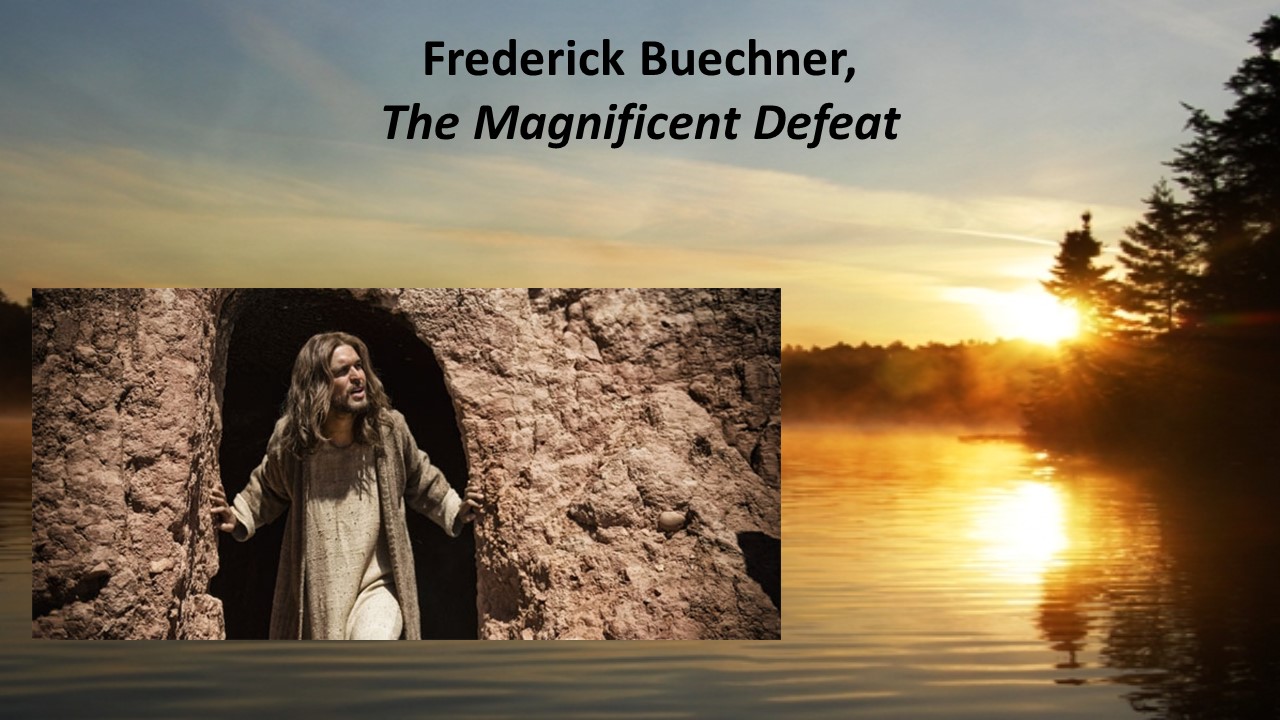

Fredrick Buechner visualizes the resurrection this way:

“Remember Jesus of Nazareth, staggering on broken feet out of the tomb toward the Resurrection, bearing on his body the proud insignia of the defeat which is victory, the magnificent defeat of the human soul at the hands of God.”[2]

The resurrection is victory over all that is evil and corrupt. It’s a victory over all that’s wrong with this world. It’s a victory over death! The cross is not the final word. We deserve death for our sin, but God cancels what is owed and through Jesus Christ, offers us life. Let’s hear what Paul has to say: Read 1st Corinthians 15:1-11)

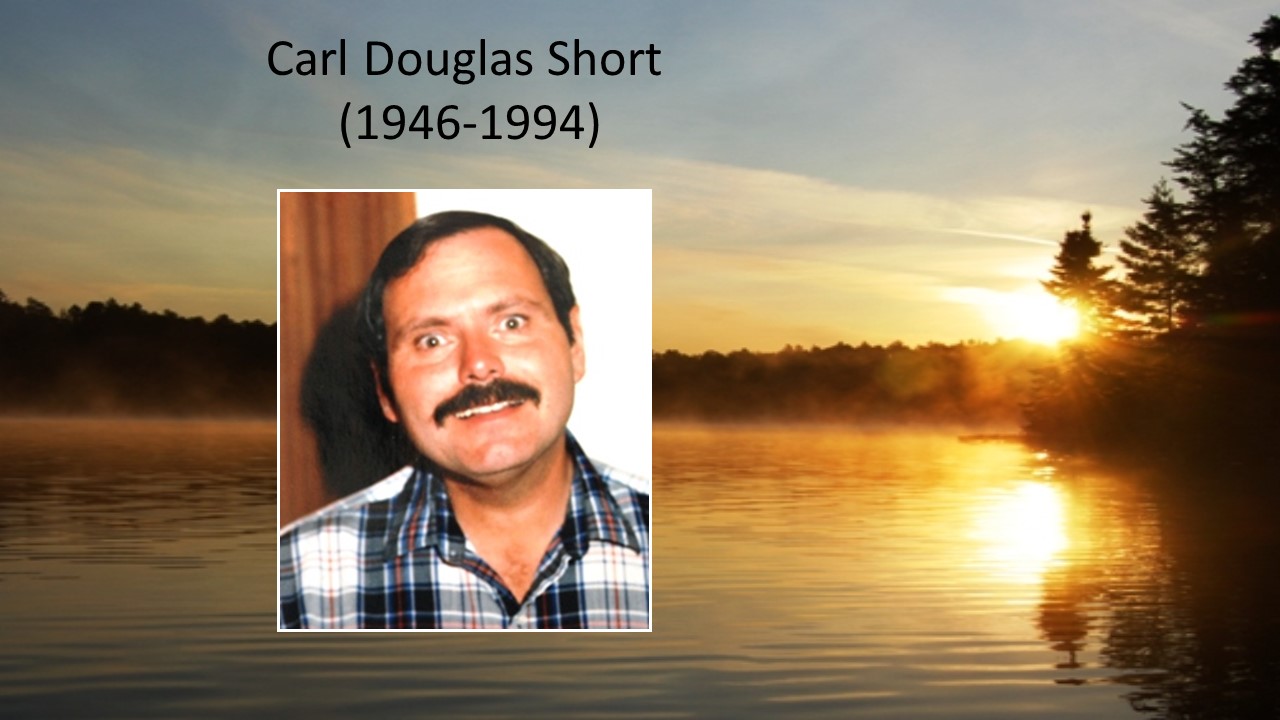

It was about this time of the year that Elvira showed up at church one Sunday morning. It was during my first year as a pastor in Cedar City, Utah. She was a frail woman and asked that we pray for her son, Carl, who was battling cancer. We did. Over the next few weeks she kept coming and I got to know her better. She was living in an adult foster home as her daughter, who’d moved her from Nebraska to the daughter’s home in Utah, couldn’t deal with her anymore. I also learned that she had not seen her son in years, even though he was now living in Las Vegas, just a three hour drive away.

A few months later, her daughter who lived in St. George, about fifty miles away, came to see me. “I need to explain my mother,” she said. I felt she was looking for me to relieve her of guilt for having placed her mother in this adult foster home. She got more than she’d bargained for that afternoon. When she left my office, she more troubled than when she had arrived, and I can only credit it to God. For you see, as she was telling me about her mother, she started to talk about her good-for-nothing brother, the one for whom we’d been praying. She couldn’t understand why he mattered so much to her mother. As she talked, things began to click in my mind.

“Wait just a minute,” I finally interrupted. “Your brother, Carl, does he also go by Doug.” There was a period of silence. She turned pale. I had my answer. It was awkward.

His name was Carl Douglas and he had lived in Virginia City when I was a student pastor there. In the five or so years in between, I’d lost track of Doug, but I had been with him when the doctor had given him the bad news that he had cancer. When I last talked to him, it was in remission, but had come back with a vengeance. I’d been praying for this friend, without knowing it, for months. And now I was sitting across from his estranged sister. Unlike her, I had only good memories of her brother. New Year’s Eve 1988 was one. It was a Saturday and we both had plans for the evening, but when I was in the church practicing my sermon I heard water running and after checking found there was a busted pipe in the heating system, underneath the organ. Doug came right down and we spent a couple of hours fixing the pipe so that we might have heat for Sunday. That was only one example. He was known of his kindness, for being quick to offer a hand to those in need.

His name was Carl Douglas and he had lived in Virginia City when I was a student pastor there. In the five or so years in between, I’d lost track of Doug, but I had been with him when the doctor had given him the bad news that he had cancer. When I last talked to him, it was in remission, but had come back with a vengeance. I’d been praying for this friend, without knowing it, for months. And now I was sitting across from his estranged sister. Unlike her, I had only good memories of her brother. New Year’s Eve 1988 was one. It was a Saturday and we both had plans for the evening, but when I was in the church practicing my sermon I heard water running and after checking found there was a busted pipe in the heating system, underneath the organ. Doug came right down and we spent a couple of hours fixing the pipe so that we might have heat for Sunday. That was only one example. He was known of his kindness, for being quick to offer a hand to those in need.

Soon after this meeting with his sister, I was in Las Vegas and was able to see Doug. He was pretty sick and knew he was going to die, but he was in good spirits and happy to see me and to hear about his mom. He asked me to officiate at his funeral. I agreed. A few weeks later, he rebounded a bit and some friends brought him up to Cedar City where he was reunited with his mother. We all had lunch together. It would be the last time Doug saw his mother. He died a few weeks later. His sister still didn’t want anything to do with him, even in death, so when I drove down to Vegas to officiate at his funeral, I took his mother along. Since Doug had lived there for less than a year, there were only a dozen or so people at the service—his mom, his son, and a few friends.

A few months after the funeral, Elvira arranged to move back to Nebraska. When I think about all this, I’m amazed. I see God’s hand at work. What was the probability Elvira would end up in a church in a distant city where the pastor knew her son? There was actually a good chance her son could have died and she’d never seen him or even been able to attend the funeral, or even know of his death. Thankfully, she was able to see him and attend his funeral. God enjoys working to bring about surprises and joy!

few months after the funeral, Elvira arranged to move back to Nebraska. When I think about all this, I’m amazed. I see God’s hand at work. What was the probability Elvira would end up in a church in a distant city where the pastor knew her son? There was actually a good chance her son could have died and she’d never seen him or even been able to attend the funeral, or even know of his death. Thankfully, she was able to see him and attend his funeral. God enjoys working to bring about surprises and joy!

This all happened 25 years ago. I doubt Elvira is still with us. She wasn’t in the best of health and in her late 70s at the time. But in a way, she got to experience a “resurrection” of her son and that’s something special. And the best of it. It was only an appetizer to the resurrection to come.

If you look at the first verse of this chapter, you’ll see that Paul begins this section of his letter by reminding the Corinthians of what he had proclaimed to them, what they had received, and upon which they’d taken a stand. One has to first hear the good news, then accept it, internalize it, believe it and share it. It’s all necessary to complete this process of being saved. But some in Corinthian must not have taken those last steps. They’d heard the gospel preached, they listened, but they never lived it, they never internalized it and now they are beginning to question the whole concept.

Imagine hearing this letter (there were only a few people back then who could read and furthermore, with only one copy of the letter, most people would be listening to it). Think about what it was like when it was being read. You listen. Some in the room maybe getting nervous for they’ve denied the resurrection. They’re feeling the point of Paul’s pen.

In the middle of verse three, Paul cites an early creed of the church. A creed is a summary of the faith. Sometimes we recite the Apostle’s Creed, but this creed is even shorter. It testifies to five things:

Christ died for our sins.

His death was accordance to scripture.

He was buried which indicates that he really was dead, not just passed out.

He then rose from the dead on the third day and finally,

He appeared to a whole bunch of people.

From the very beginning of the church, this creed testifies to the importance of the resurrection for understanding the faith. Without it, the church has no reason to exist.

The listing of those to whom Christ appears is interesting. Paul acknowledges that he’s a latecomer. Paul also doesn’t mention the women at the tomb, instead starts his list with Cephas or Peter. Some scholars have suggested this is because Paul is a chauvinist, but that’s probably not the case. Instead, if we went back to the beginning of the letter, you’ll see that one of the divisions in Corinth involved those who followed Peter instead of Paul. Most of these believers were Jewish, which is why Paul uses Cephas, Peter’s Jewish name. We also know that Paul and Peter had significant differences. By beginning with Peter, Paul may be trying to mend fences. Besides, the Corinthians know Peter, but they probably didn’t know the various Marys and others who were there at the grave.

In the spirit of mending fences, Paul tacks on Christ’s appearance to him at the end of his list. He humbles himself, acknowledges that before this appearance he didn’t believe. He had persecuted the church. When Christ appeared to him, he was most undeserving. But it’s that way with grace; we’re all undeserving (that includes you and me). Paul does mention that he has worked harder than anyone for Christ, yet even that he credits to the grace of God.

N. T. Wright, an insightful theologian from the British Anglican community says this:

N. T. Wright, an insightful theologian from the British Anglican community says this:

“Jesus’s resurrection is the beginning of God’s new project not to snatch people away from earth to heaven but to colonize earth with the life of heaven. That, after all, is what the Lord’s Prayer is about.” [3]

We pray, “Thy kingdom come,” and the kingdom begins as Christ is raised from the grave. The cross is important, my friends, but the resurrection is what makes our life of faith worth living. In it, we have hope, for we know that our God loves to surprise us with joy. In the same book, Wright also writes:

“The message of Easter is that God’s new world has been unveiled in Jesus Christ and that you’re now invited to belong to it.”

In other words, because of the resurrection, we’re now invited to live as God intends as we join God in his work of transforming the world—a transformation that begins with the open tomb on Easter morning. Everything will be changed. Jesus has defeated death and inaugurates the reclamation of the earth for God’s purpose.

In other words, because of the resurrection, we’re now invited to live as God intends as we join God in his work of transforming the world—a transformation that begins with the open tomb on Easter morning. Everything will be changed. Jesus has defeated death and inaugurates the reclamation of the earth for God’s purpose.

Will we believe? Will we allow ourselves to be transformed? God is working miracles in this world. I shared one such miracle at the beginning of the sermon. God wants to reconcile the world, not just to himself, but between mother and son, brothers and sisters, friends and enemies. Will we accept God’s invitation to proclaim the good news? Will we accept the invitation to hop up on the bandwagon and follow Jesus, out of the grave and into life? Let us pray:

Will we believe? Will we allow ourselves to be transformed? God is working miracles in this world. I shared one such miracle at the beginning of the sermon. God wants to reconcile the world, not just to himself, but between mother and son, brothers and sisters, friends and enemies. Will we accept God’s invitation to proclaim the good news? Will we accept the invitation to hop up on the bandwagon and follow Jesus, out of the grave and into life? Let us pray:

Almighty God, who gives life to the dead, we thank you for Jesus’ resurrection and pray that you will help all of us to be his faithful disciples, sharing his life and his hope to a confused and lost world. We ask this in Jesus’ name. Amen.

©2019

[1] See Kenneth E. Bailey, Paul Through Mediterranean Eyes: Cultural Studies in 1 Corinthians (Intervarsity Press, 2011).

[2] Frederick Buechner, The Magnificent Defeat

[3] N.T. Wright, Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison  Do you think the Pharisees might have been picking on Jesus for the wrong reason? They get all over him for harvesting grain on the Sabbath, but don’t say anything about the fact Jesus and his disciples are in someone else’s grain field? Think about this for a moment as I go off on a tangent.

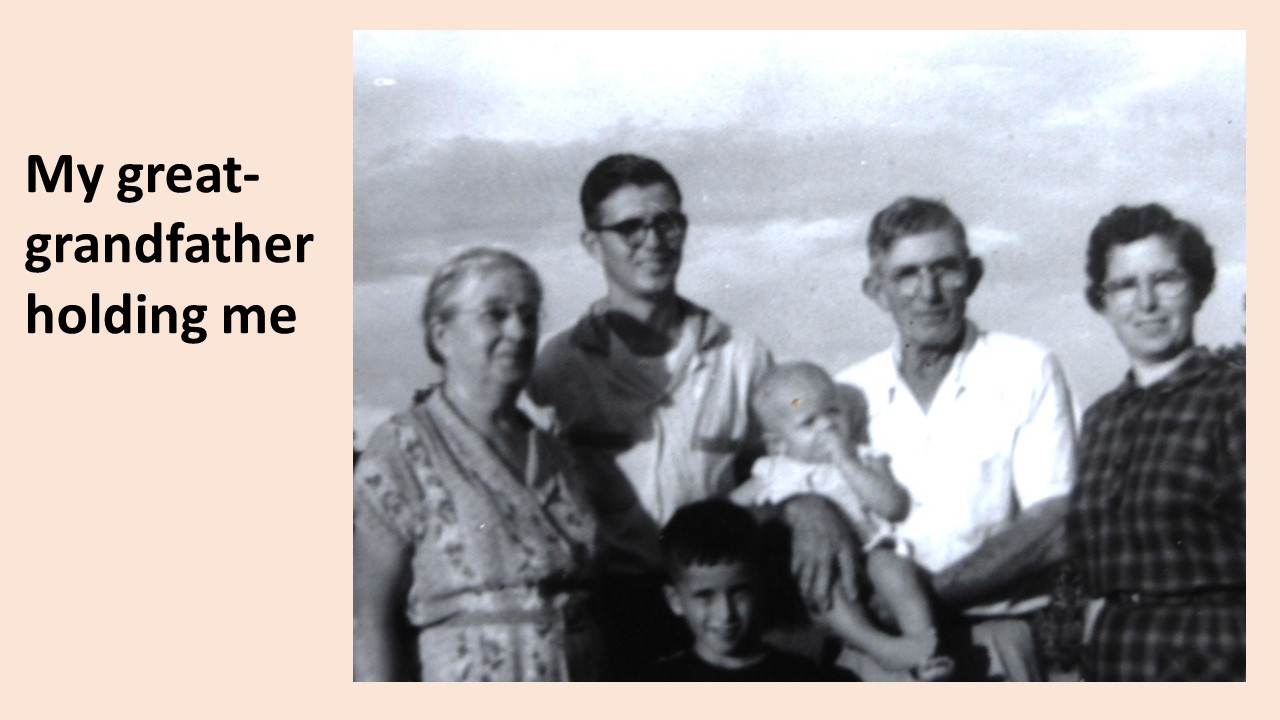

Do you think the Pharisees might have been picking on Jesus for the wrong reason? They get all over him for harvesting grain on the Sabbath, but don’t say anything about the fact Jesus and his disciples are in someone else’s grain field? Think about this for a moment as I go off on a tangent. I inherited my Presbyterianism from my great-granddaddy McKenzie. He was a strong church leader who served as an elder at Culdee Presbyterian Church for over 40 years. It was the church his father and grandfather help establish in those dark days following the War Between the States. Like most churches in the day, it emphasized the fear of God and the preacher regularly reminded the congregation about God’s judgment.

I inherited my Presbyterianism from my great-granddaddy McKenzie. He was a strong church leader who served as an elder at Culdee Presbyterian Church for over 40 years. It was the church his father and grandfather help establish in those dark days following the War Between the States. Like most churches in the day, it emphasized the fear of God and the preacher regularly reminded the congregation about God’s judgment. This brings me back to the subject of Jesus and the disciples munching in some farmer’s field on the Sabbath. The reason the Pharisees didn’t get on Jesus for his disciples harvesting food that didn’t belong to them was that Jewish law allowed one to pluck grain with their hands from their neighbor’s field. According to Deuteronomy, we’re told:

This brings me back to the subject of Jesus and the disciples munching in some farmer’s field on the Sabbath. The reason the Pharisees didn’t get on Jesus for his disciples harvesting food that didn’t belong to them was that Jewish law allowed one to pluck grain with their hands from their neighbor’s field. According to Deuteronomy, we’re told: Jesus is doing something knew. Our passage begins with an illustration about patching coats and wineskins. This is probably not something any of us have experienced for we either replace our coats or take them to the tailor on Montgomery Cross. And our wine is aged in barrels and tends to come to us in bottles. But back in the first century, you had to patch your coats, and skins were used to hold wine. So you made sure the cloth you used to patch something was preshrunk and that your wineskins were new so that it would stretch and not bust open during the fermenting process.

Jesus is doing something knew. Our passage begins with an illustration about patching coats and wineskins. This is probably not something any of us have experienced for we either replace our coats or take them to the tailor on Montgomery Cross. And our wine is aged in barrels and tends to come to us in bottles. But back in the first century, you had to patch your coats, and skins were used to hold wine. So you made sure the cloth you used to patch something was preshrunk and that your wineskins were new so that it would stretch and not bust open during the fermenting process. As the Sabbath is made for us, we should consider how it was understood in the early church. Paul tells the Romans that some think one day is better than another while others think all days are equal, and in Colossians he says we shouldn’t let ourselves be judged over the Sabbath.

As the Sabbath is made for us, we should consider how it was understood in the early church. Paul tells the Romans that some think one day is better than another while others think all days are equal, and in Colossians he says we shouldn’t let ourselves be judged over the Sabbath. The Sabbath Command is a reminder that we are not able to run ragged 24/7. We need rest, both daily (which is why night was created), and for an extended period at least once a week. The Sabbath is a day we can put our employment concerns aside, and just enjoy the creation God has given us. It’s a day we can enjoy the families that God has given us. It’s a day we can catch our breath and look around and give thanks.

The Sabbath Command is a reminder that we are not able to run ragged 24/7. We need rest, both daily (which is why night was created), and for an extended period at least once a week. The Sabbath is a day we can put our employment concerns aside, and just enjoy the creation God has given us. It’s a day we can enjoy the families that God has given us. It’s a day we can catch our breath and look around and give thanks. When I was a small child we lived on a parcel next to my great-grandparents farm. On occasion, we ate Sunday dinner with them. First thing my great-grandma did when she got home from church was make biscuits. Much of the dinner was already prepared but the biscuits had to be fresh. First, she’d take some kindling and light a fire in her wood burning stove. Don’t get the idea that we were hillbillies because my great-grandma had a perfectly good gas range sitting in her kitchen, it’s just that she preferred the wood burning stove for most of her cooking. After her death in the summer of ’64, the wood burning range was taken out, but before then I have good memories, as a five or six year old, gathering up chucks of stove wood my great-granddaddy had split. As the oven heated up, my great-grandma mixed up some flour, salt, and baking soda, cut in some lard, then added buttermilk. She’d knead the gluey glob till it was smooth, rolled it out, and cut out the biscuits. Soon a heavenly scent filled the room.

When I was a small child we lived on a parcel next to my great-grandparents farm. On occasion, we ate Sunday dinner with them. First thing my great-grandma did when she got home from church was make biscuits. Much of the dinner was already prepared but the biscuits had to be fresh. First, she’d take some kindling and light a fire in her wood burning stove. Don’t get the idea that we were hillbillies because my great-grandma had a perfectly good gas range sitting in her kitchen, it’s just that she preferred the wood burning stove for most of her cooking. After her death in the summer of ’64, the wood burning range was taken out, but before then I have good memories, as a five or six year old, gathering up chucks of stove wood my great-granddaddy had split. As the oven heated up, my great-grandma mixed up some flour, salt, and baking soda, cut in some lard, then added buttermilk. She’d knead the gluey glob till it was smooth, rolled it out, and cut out the biscuits. Soon a heavenly scent filled the room. When the meal was over, if it was meal without pie, my great-granddaddy would get up and go to the pantry and come back with a jar of molasses or honey. He’d drop a big plop of butter in his plate, pour on the sweetener, and mix it up real good with his folk. Then, throwing away all manners, he’d sop it up with the left-over biscuits. It was good. Afterwards, we kids would run out and play while the adults retired to either the back porch or, if in winter, the parlor. When we’d come back in an hour or so later, they’d all be napping.

When the meal was over, if it was meal without pie, my great-granddaddy would get up and go to the pantry and come back with a jar of molasses or honey. He’d drop a big plop of butter in his plate, pour on the sweetener, and mix it up real good with his folk. Then, throwing away all manners, he’d sop it up with the left-over biscuits. It was good. Afterwards, we kids would run out and play while the adults retired to either the back porch or, if in winter, the parlor. When we’d come back in an hour or so later, they’d all be napping. Jesus in this story doesn’t negate the Sabbath. He just encourages us to use it as it was created, for our benefit. Take a deep breath. Receive the Sabbath as a gift from a gracious God. Amen.

Jesus in this story doesn’t negate the Sabbath. He just encourages us to use it as it was created, for our benefit. Take a deep breath. Receive the Sabbath as a gift from a gracious God. Amen.

Our Lenten series encourages us to slow down, take a deep breath, and reconnect to an unhurried God. How might this passage encourage us to make such connections?

Our Lenten series encourages us to slow down, take a deep breath, and reconnect to an unhurried God. How might this passage encourage us to make such connections?

This list reminds us that, like the seasons, there is a cycle to our lives. If Solomon had lived by the ocean, he might have added the tides. The cycles of life are all around us, but some are experienced more frequently than others. If we accept God’s sovereignty, there is no need for us to constantly be distraught over life’s ebbing and waning. We are freed to enjoy what we can while trusting and having faith that things won’t always be bad.

This list reminds us that, like the seasons, there is a cycle to our lives. If Solomon had lived by the ocean, he might have added the tides. The cycles of life are all around us, but some are experienced more frequently than others. If we accept God’s sovereignty, there is no need for us to constantly be distraught over life’s ebbing and waning. We are freed to enjoy what we can while trusting and having faith that things won’t always be bad.

In his acknowledgements at the beginning of his book on aging which I read this past week, Parker Palmer, a spiritual author from the Quaker tradition, writes:

In his acknowledgements at the beginning of his book on aging which I read this past week, Parker Palmer, a spiritual author from the Quaker tradition, writes:

We can’t control when the cycles of life happen, but we can control how we respond to them. Receive them as a gift, as grace. Amen.

We can’t control when the cycles of life happen, but we can control how we respond to them. Receive them as a gift, as grace. Amen.

Arthur Brooks, one of this year’s Calvin January Series speakers, had a new book come out this month. I read the first half of it this past week. It’s titled, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America from the Culture of Contempt. I highly recommend it. Brooks’ points out that anger isn’t our problem. What he sees as a problem is contempt. When we are angry, we are generally wanting something better. When we hold someone in contempt, we are essentially wishing they didn’t exist. In a chapter titled “The Culture of Contempt,” he suggests that much of America, even though we hate it, are addicted—there’s that word again—to political contempt. We don’t like what this contempt does to us (not to mention those we disagree with), but we can’t seem to get enough of it. Like a junkie, we “indulge” in the habit. And the media, who has economic interest in our addiction, is more than happy to feed us.

Arthur Brooks, one of this year’s Calvin January Series speakers, had a new book come out this month. I read the first half of it this past week. It’s titled, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America from the Culture of Contempt. I highly recommend it. Brooks’ points out that anger isn’t our problem. What he sees as a problem is contempt. When we are angry, we are generally wanting something better. When we hold someone in contempt, we are essentially wishing they didn’t exist. In a chapter titled “The Culture of Contempt,” he suggests that much of America, even though we hate it, are addicted—there’s that word again—to political contempt. We don’t like what this contempt does to us (not to mention those we disagree with), but we can’t seem to get enough of it. Like a junkie, we “indulge” in the habit. And the media, who has economic interest in our addiction, is more than happy to feed us. Do any of you remember the old movie, City Slickers? It doesn’t seem to be old, but the movie was released in 1991. It starred Billy Crystal who, with a group of his friends from the city, decide to go out west for a few weeks to help round up cattle. In one scene, Crystal is riding on a horse beside Curly, an old fashion cowboy who could have been the Marlboro Man. When Crystals asks about his secret to being content in life, Curly points his index finger and says it’s this. Crystal is confused and asks, “You’re finger?” Curly shakes his head and replies it’s just one thing. Of course, Curly isn’t able to tell Crystal what’s his one thing is, that’s for him to find out. This “one thing” is now known as Curly’s law.

Do any of you remember the old movie, City Slickers? It doesn’t seem to be old, but the movie was released in 1991. It starred Billy Crystal who, with a group of his friends from the city, decide to go out west for a few weeks to help round up cattle. In one scene, Crystal is riding on a horse beside Curly, an old fashion cowboy who could have been the Marlboro Man. When Crystals asks about his secret to being content in life, Curly points his index finger and says it’s this. Crystal is confused and asks, “You’re finger?” Curly shakes his head and replies it’s just one thing. Of course, Curly isn’t able to tell Crystal what’s his one thing is, that’s for him to find out. This “one thing” is now known as Curly’s law. I suggest that the one thing Jesus points out to Martha was himself. Serving others is good, doing a good deed such as feeding visitors is commendable, but there is a deeper human need and if we don’t ground ourselves there, we burn out. As humans, we have a need to connect with others and as a Christian, our need includes a connection to Jesus. How do we go about this? Let’s see what our text says.

I suggest that the one thing Jesus points out to Martha was himself. Serving others is good, doing a good deed such as feeding visitors is commendable, but there is a deeper human need and if we don’t ground ourselves there, we burn out. As humans, we have a need to connect with others and as a Christian, our need includes a connection to Jesus. How do we go about this? Let’s see what our text says. Jesus isn’t telling Martha to be inhospitable. Hospitality is an important trait of Christians. We are told in the book of Hebrews: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for in doing so some have entertained angels without even knowing it.”

Jesus isn’t telling Martha to be inhospitable. Hospitality is an important trait of Christians. We are told in the book of Hebrews: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for in doing so some have entertained angels without even knowing it.” Finally, Martha has enough. Here, she is fixing a nice sit-down dinner, and while she’s working, her sister enjoys Jesus’ company. Perhaps, Martha’s a little envious… She tries to get Jesus on her side by appealing to his compassion. “Lord, doesn’t it bother you that I’ve had to do all the work?” she asks. Reading between the lines, we get the idea she really wants to say, “Tell Ms. Couch Potato to get in here and help…” Do you sense the contempt is rising in Martha?

Finally, Martha has enough. Here, she is fixing a nice sit-down dinner, and while she’s working, her sister enjoys Jesus’ company. Perhaps, Martha’s a little envious… She tries to get Jesus on her side by appealing to his compassion. “Lord, doesn’t it bother you that I’ve had to do all the work?” she asks. Reading between the lines, we get the idea she really wants to say, “Tell Ms. Couch Potato to get in here and help…” Do you sense the contempt is rising in Martha? Are we like Martha? Do we worry and become distracted over so many things that we are unable to see what’s truly important? Do we keep our lives so busy that we have no real quality time to spend with friends? (I’m guilty). If so, we just might be missing something important… After all, Martha missed a chance to spend time listening to our Lord’s teachings. Don’t forget about hospitality, but remember that it’s not the only thing.

Are we like Martha? Do we worry and become distracted over so many things that we are unable to see what’s truly important? Do we keep our lives so busy that we have no real quality time to spend with friends? (I’m guilty). If so, we just might be missing something important… After all, Martha missed a chance to spend time listening to our Lord’s teachings. Don’t forget about hospitality, but remember that it’s not the only thing. You know, this is a busy time here at Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church. The Session has begun working on a strategic plan for the future. A small group of Elders have spent a lot of time on this project. This week, the rest of the Elders will join in the process, and then we’ll be asking for your help and ideas. This is good and needed work, but I encourage us to not be distracted from that which we truly need… Jesus Christ. Without Jesus, what we do will mean nothing. He’s our reason for being, for he calls us together in communion with him. So remember the main thing. Make sure to take time to spend with Jesus, daily. If you do, the rest will fall into place. Amen.

You know, this is a busy time here at Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church. The Session has begun working on a strategic plan for the future. A small group of Elders have spent a lot of time on this project. This week, the rest of the Elders will join in the process, and then we’ll be asking for your help and ideas. This is good and needed work, but I encourage us to not be distracted from that which we truly need… Jesus Christ. Without Jesus, what we do will mean nothing. He’s our reason for being, for he calls us together in communion with him. So remember the main thing. Make sure to take time to spend with Jesus, daily. If you do, the rest will fall into place. Amen.

We’re looking at the 23rd Psalm today. It’s a prayer of faith not often heard on Sunday mornings; we save it for funerals. Wayne Muller in book, Sabbath, Restoring the Sacred Rhythm of Rest, points this out:

We’re looking at the 23rd Psalm today. It’s a prayer of faith not often heard on Sunday mornings; we save it for funerals. Wayne Muller in book, Sabbath, Restoring the Sacred Rhythm of Rest, points this out:

The Northeast Cape Fear River broadens and deepens as it flows through Holly Shelter Swamp. In this area, on a high bluff on the east bank of the river was my scout troop’s favorite camping site. The ridge was forested with tall long-leaf pines. Lining the banks along the river were dogwoods, tupelo and cypress, their branches adorned with Spanish moss. The leisurely pace of the river invited us boys to sit on its banks and throw sticks into the water, watching them slowly float away. It’s the type of life Mark Twain wrote about on the Mississippi, a life of ease beside peaceful waters that seem to hold some mysterious power to heal, to forget our troubles, and to be renewed.

The Northeast Cape Fear River broadens and deepens as it flows through Holly Shelter Swamp. In this area, on a high bluff on the east bank of the river was my scout troop’s favorite camping site. The ridge was forested with tall long-leaf pines. Lining the banks along the river were dogwoods, tupelo and cypress, their branches adorned with Spanish moss. The leisurely pace of the river invited us boys to sit on its banks and throw sticks into the water, watching them slowly float away. It’s the type of life Mark Twain wrote about on the Mississippi, a life of ease beside peaceful waters that seem to hold some mysterious power to heal, to forget our troubles, and to be renewed. In the late afternoon, things would change. As the sun dropped in the west behind trees, it created long shadows on the black waters. An eeriness descended. Spanish moss now appeared as the long beards of men whose mysterious and untimely death occurred in the backwaters of Holly Shelter Swamp. We had been warned.

In the late afternoon, things would change. As the sun dropped in the west behind trees, it created long shadows on the black waters. An eeriness descended. Spanish moss now appeared as the long beards of men whose mysterious and untimely death occurred in the backwaters of Holly Shelter Swamp. We had been warned. Yea through I walk through the valley of the shadow of death.” This most beloved psalm, as I pointed out, is ubiquitously used at funerals and mostly overlooked on Sunday mornings. This is unfortunate for the psalm tells us about a life lived well—a life lived in complete trust of God the Father.

Yea through I walk through the valley of the shadow of death.” This most beloved psalm, as I pointed out, is ubiquitously used at funerals and mostly overlooked on Sunday mornings. This is unfortunate for the psalm tells us about a life lived well—a life lived in complete trust of God the Father. Psalm 23 is attributed to King David and it certainly brings to mind key elements of his early life. As a young shepherd, he knew what it meant to lead sheep through dangerous mountainous terrain. As a mere boy, he was willing to face the giant Goliath on the battlefield. As a young man, he was being chased by the armies of King Saul, who knew he was God’s anointed. And even as an old man with many enemies, he knew the pain of having his own son attempting to take his throne. Of course, we know David had many short-comings, but he made up for them by putting his faith in God’s hands. David was a man, the scriptures tell us, after the very heart of God.

Psalm 23 is attributed to King David and it certainly brings to mind key elements of his early life. As a young shepherd, he knew what it meant to lead sheep through dangerous mountainous terrain. As a mere boy, he was willing to face the giant Goliath on the battlefield. As a young man, he was being chased by the armies of King Saul, who knew he was God’s anointed. And even as an old man with many enemies, he knew the pain of having his own son attempting to take his throne. Of course, we know David had many short-comings, but he made up for them by putting his faith in God’s hands. David was a man, the scriptures tell us, after the very heart of God. The opening verse captures the essence of the Psalm. “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.” The Psalm begins with a powerful metaphor of God as a shepherd. Of course, God is more than just a shepherd, which was a lowly occupation in ancient Israel. God is the Creator, the judge, the warrior, the righteous one, the ancient one. All these images remind us that God is greater than just a mere tender of sheep, but like a shepherd who is devoted to his sheep, God is devoted to his people, which makes the shepherd image the perfect depiction of our relationship with God the Creator.

The opening verse captures the essence of the Psalm. “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.” The Psalm begins with a powerful metaphor of God as a shepherd. Of course, God is more than just a shepherd, which was a lowly occupation in ancient Israel. God is the Creator, the judge, the warrior, the righteous one, the ancient one. All these images remind us that God is greater than just a mere tender of sheep, but like a shepherd who is devoted to his sheep, God is devoted to his people, which makes the shepherd image the perfect depiction of our relationship with God the Creator. There are two great images at the end of this Psalm. First, there is a table set in the presence of our enemies. Royal banquets are often used in scripture to point to an eschatological future, the promised heavenly banquet where Jesus is at the head of the table and serves us. Perhaps the presence of our enemies is an invitation for them, too, to come to the table. They, too, have been created by a God who delights in bringing about reconciliation and encourages us to seek out peace with our enemies.

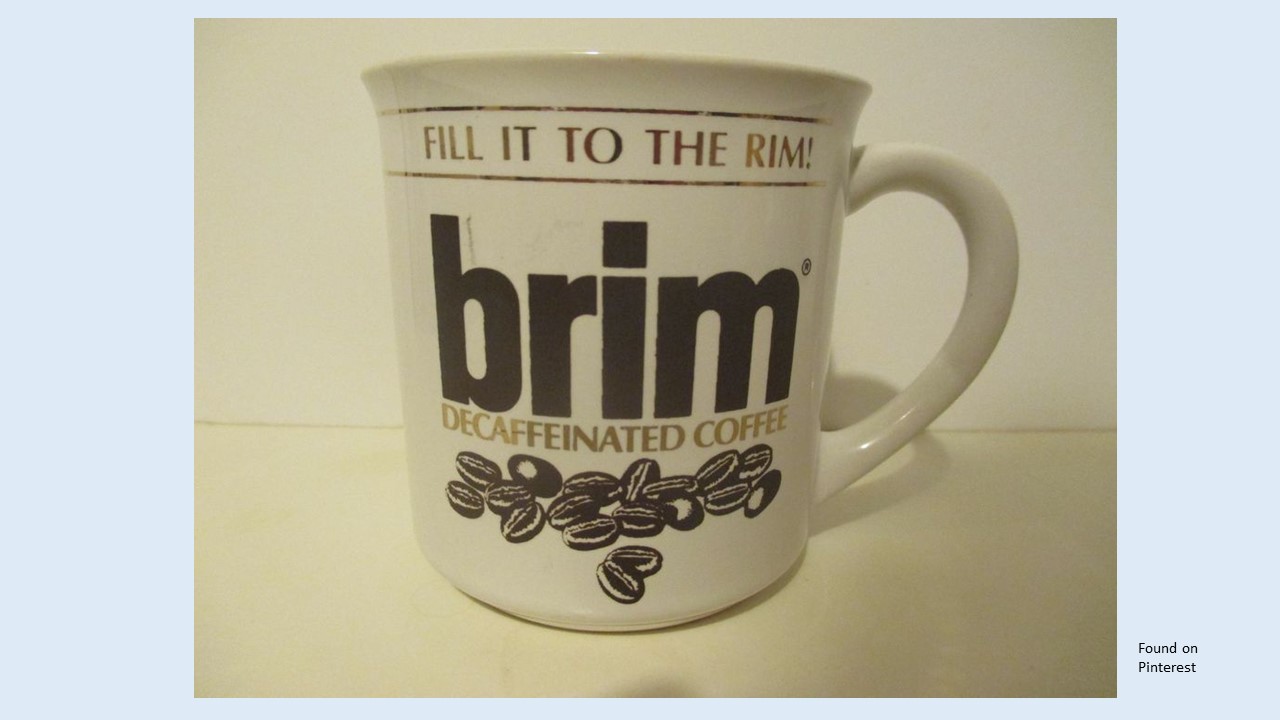

There are two great images at the end of this Psalm. First, there is a table set in the presence of our enemies. Royal banquets are often used in scripture to point to an eschatological future, the promised heavenly banquet where Jesus is at the head of the table and serves us. Perhaps the presence of our enemies is an invitation for them, too, to come to the table. They, too, have been created by a God who delights in bringing about reconciliation and encourages us to seek out peace with our enemies. The second image is the cup running over. Back in the 70s and 80s, Brim decaffeinated coffee had a series of advertisements about filling our coffee cups to the rim. We don’t serve Brim in the fellowship hall. The ad world is a perfect one and no one that I remember in those commercials spilled coffee on the rug, even when the cup couldn’t contain another drop. But here, in Psalm 23, we’re promised something even greater that being filled to the rim. Our cup overflows! This is a promise of abundance.

The second image is the cup running over. Back in the 70s and 80s, Brim decaffeinated coffee had a series of advertisements about filling our coffee cups to the rim. We don’t serve Brim in the fellowship hall. The ad world is a perfect one and no one that I remember in those commercials spilled coffee on the rug, even when the cup couldn’t contain another drop. But here, in Psalm 23, we’re promised something even greater that being filled to the rim. Our cup overflows! This is a promise of abundance. When things are looking down, when life is busy and we can’t seem to get a break, we can go to this Psalm and be reminded that we are not alone. God’s goodness abounds. God’s goodness will overflow in our hearts and lives, giving us a new perspective on the challenges we face. Amen.

When things are looking down, when life is busy and we can’t seem to get a break, we can go to this Psalm and be reminded that we are not alone. God’s goodness abounds. God’s goodness will overflow in our hearts and lives, giving us a new perspective on the challenges we face. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

You know, when it comes to religion, we often think it’s about being good, or good enough. We think we need to be like Jig in one of his purifying stages. We see religion as hard work which is why many people don’t want to be bothered with it. We forget about the joy of salvation.

You know, when it comes to religion, we often think it’s about being good, or good enough. We think we need to be like Jig in one of his purifying stages. We see religion as hard work which is why many people don’t want to be bothered with it. We forget about the joy of salvation.

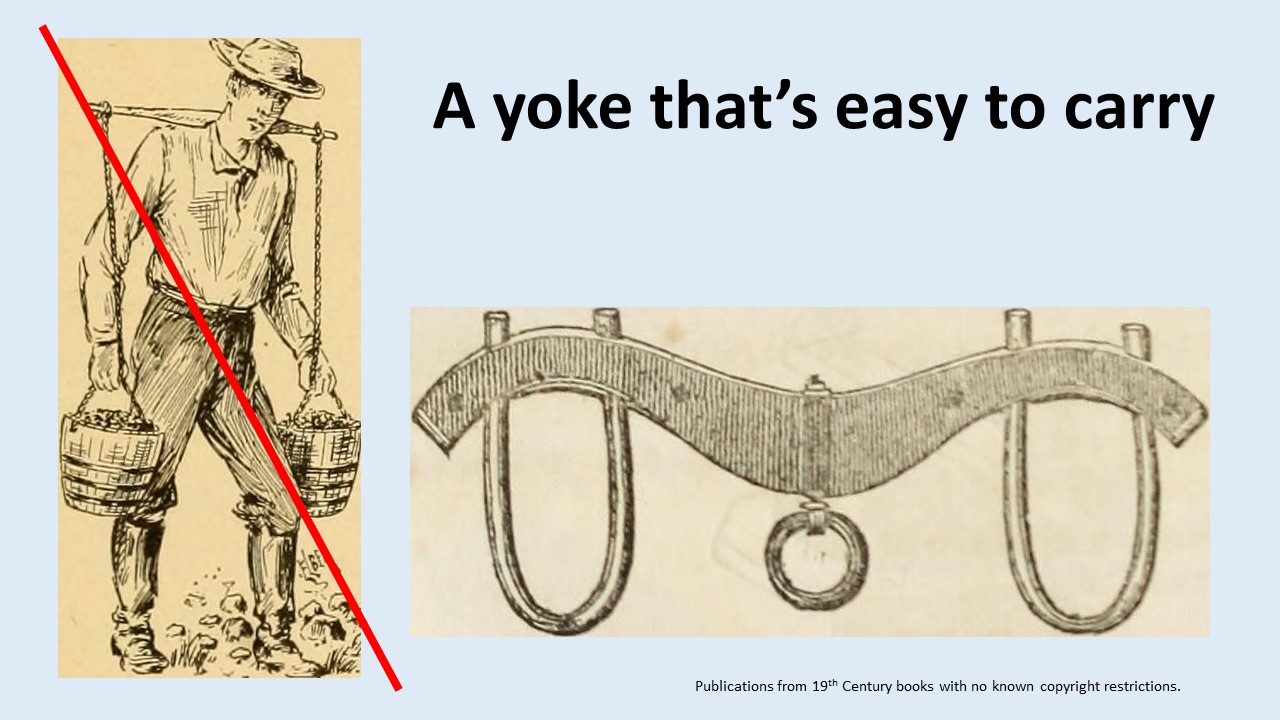

So Jesus invites us saying, “Come to me; take my yoke.” He’s not talking about a single yoke, one that he gives us and we wear around so that we might haul a heavy load. Instead, I think he offers a double yoke, one that he helps share the load. One in which we are able to watch him and learn how to live graciously, to appreciate beauty and to give thanks for the blessings of life. Our translation tells us Jesus’ yoke is easy, but it could also be translated as kind

So Jesus invites us saying, “Come to me; take my yoke.” He’s not talking about a single yoke, one that he gives us and we wear around so that we might haul a heavy load. Instead, I think he offers a double yoke, one that he helps share the load. One in which we are able to watch him and learn how to live graciously, to appreciate beauty and to give thanks for the blessings of life. Our translation tells us Jesus’ yoke is easy, but it could also be translated as kind

esus calls us to come and learn from him how to enjoy life. He calls us to relearn our priorities, to set the right tempo. Instead of having to work hard to earn God’s grace, we accept it and thereby joyously labor not for God’s grace but to praise God for having been so good to us. We don’t have to be so rushed, because we know God is in control. We don’t have to do it all, for we trust in God’s providence. We don’t have to pretend to be God. Let that burden go!

esus calls us to come and learn from him how to enjoy life. He calls us to relearn our priorities, to set the right tempo. Instead of having to work hard to earn God’s grace, we accept it and thereby joyously labor not for God’s grace but to praise God for having been so good to us. We don’t have to be so rushed, because we know God is in control. We don’t have to do it all, for we trust in God’s providence. We don’t have to pretend to be God. Let that burden go! Take care of yourself. Reorient your life to a new perspective, one with Jesus, as the face of God

Take care of yourself. Reorient your life to a new perspective, one with Jesus, as the face of God

We are coming to the end of our series on the “Land Between,” and our study from the 11th Chapter of the Book of Numbers. Next week, we’ll begin our Lent Journey, as we make our way toward Easter. Our theme for our Lenten series will be “Busy.” It’s a timely series; we all struggle with busyness. As a way of catching our breath, we’re going to be encouraged by scripture to reconnect to an unhurried God. As a warning, we’ll be doing a few different things in worship. It’ll be exciting, so come and invite others who feel hurried in life to join us for a refreshing break each week as we gather on Sunday.

We are coming to the end of our series on the “Land Between,” and our study from the 11th Chapter of the Book of Numbers. Next week, we’ll begin our Lent Journey, as we make our way toward Easter. Our theme for our Lenten series will be “Busy.” It’s a timely series; we all struggle with busyness. As a way of catching our breath, we’re going to be encouraged by scripture to reconnect to an unhurried God. As a warning, we’ll be doing a few different things in worship. It’ll be exciting, so come and invite others who feel hurried in life to join us for a refreshing break each week as we gather on Sunday.

Little Tommy was riding in the backseat as the family came home from church. “What did you learn in Sunday School today,” his father asked.

Little Tommy was riding in the backseat as the family came home from church. “What did you learn in Sunday School today,” his father asked. Now back to Moses. He’s the face people see. And because they still aren’t sure what’s up, he’s the one who receives all the complaints. He’s weary and needs help. But unlike the people who have questioned God’s goodness, thinking the Almighty led them into the desert to die, Moses trusts the Lord. After all, God has always comes through. When Israel’s back was up against the sea, it wasn’t Moses who parted the sea. He might have lifted his arms as we see in the movies, but it was God, the one who watches out for Israel, who saves the day.

Now back to Moses. He’s the face people see. And because they still aren’t sure what’s up, he’s the one who receives all the complaints. He’s weary and needs help. But unlike the people who have questioned God’s goodness, thinking the Almighty led them into the desert to die, Moses trusts the Lord. After all, God has always comes through. When Israel’s back was up against the sea, it wasn’t Moses who parted the sea. He might have lifted his arms as we see in the movies, but it was God, the one who watches out for Israel, who saves the day. Let’s look at the text. After the elders were commissioned, they received the spirit and prophesied. That was all well and good, and expected. But what happens next is that there were two men, who were not in the assembly, who showed signs of having the spirit placed upon them. They, too, prophesied. This was disturbing, for these were not ones who were supposed to be doing this. A runner (a 14th Century BC tattle-tale) was sent to Moses saying, Eldad and Medad are prophesying in camp. Joshua was ready to have them stopped but it didn’t bother Moses. “Let them be,” Moses responded. “Are you jealous for me? Wouldn’t it be nice if all God’s people were prophets?”

Let’s look at the text. After the elders were commissioned, they received the spirit and prophesied. That was all well and good, and expected. But what happens next is that there were two men, who were not in the assembly, who showed signs of having the spirit placed upon them. They, too, prophesied. This was disturbing, for these were not ones who were supposed to be doing this. A runner (a 14th Century BC tattle-tale) was sent to Moses saying, Eldad and Medad are prophesying in camp. Joshua was ready to have them stopped but it didn’t bother Moses. “Let them be,” Moses responded. “Are you jealous for me? Wouldn’t it be nice if all God’s people were prophets?” What can we take from this passage? How might it apply to our topic of growth? There are two things that come to mind. First of all, as we see in the story of the Exodus, we have to take the risk to follow and to trust God. It can be scary at times, but if we are willing to take that risk, God will protect and watch over us. Faith isn’t about certainty; if it was, it wouldn’t be faith. Faith is about trust. Do we trust God enough to take a risk that will allow God to show us that he’s with us? When God’s church grapples at what its future might be, those who are willing to take a risk are the ones rewarded. It’s easy to sit back and do nothing, but that’s not the type of followers Jesus calls. As the Session of this church works on our strategic plan for the future (and this is a process), I hope you will be open to new directions. God calls us to risk in faith, not for our glory, but for God’s. Are we up for taking risks? We can’t keep doing the same thing that might have worked for us 30 or 40 years ago. Times change and new strategies are required. We are called to be people of faith and we must live into our calling.

What can we take from this passage? How might it apply to our topic of growth? There are two things that come to mind. First of all, as we see in the story of the Exodus, we have to take the risk to follow and to trust God. It can be scary at times, but if we are willing to take that risk, God will protect and watch over us. Faith isn’t about certainty; if it was, it wouldn’t be faith. Faith is about trust. Do we trust God enough to take a risk that will allow God to show us that he’s with us? When God’s church grapples at what its future might be, those who are willing to take a risk are the ones rewarded. It’s easy to sit back and do nothing, but that’s not the type of followers Jesus calls. As the Session of this church works on our strategic plan for the future (and this is a process), I hope you will be open to new directions. God calls us to risk in faith, not for our glory, but for God’s. Are we up for taking risks? We can’t keep doing the same thing that might have worked for us 30 or 40 years ago. Times change and new strategies are required. We are called to be people of faith and we must live into our calling. Secondly, we learn in this passage that we’re not in control and we need to let God’s Spirit work. Those who were upset with Eldad and Medad show a human tendency to have preconceived ideas of what it looks like when God shows up. We have to be ready for surprises, for God’s ideas may be different from ours. God has this incredible love for all people, not just those who look, think and act like us. We might be surprised what God is doing in our midst and it might make us uncomfortable. Someone might come up with a new idea that we’ve never tried before, or that was half-heartedly tried years ago. Is our first reaction to immediately reject it? Or are we willing to see if God’s Spirit’s is leading us in a different direction? The truth of Jesus Christ never changes, but how we live out that truth within a changing culture will be different.

Secondly, we learn in this passage that we’re not in control and we need to let God’s Spirit work. Those who were upset with Eldad and Medad show a human tendency to have preconceived ideas of what it looks like when God shows up. We have to be ready for surprises, for God’s ideas may be different from ours. God has this incredible love for all people, not just those who look, think and act like us. We might be surprised what God is doing in our midst and it might make us uncomfortable. Someone might come up with a new idea that we’ve never tried before, or that was half-heartedly tried years ago. Is our first reaction to immediately reject it? Or are we willing to see if God’s Spirit’s is leading us in a different direction? The truth of Jesus Christ never changes, but how we live out that truth within a changing culture will be different. Remember, it’s not about us. We’re called to have faith, to trust, and to follow Jesus as we move through the “Land Between.” And if we have faith, we will experience growth in our own lives and within the community. We might not know what that growth really looks like until afterwards, but when we are there, we will know that God has been with us. Amen.

Remember, it’s not about us. We’re called to have faith, to trust, and to follow Jesus as we move through the “Land Between.” And if we have faith, we will experience growth in our own lives and within the community. We might not know what that growth really looks like until afterwards, but when we are there, we will know that God has been with us. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Robert Ruark began quail hunting with his granddad at the age of eight. The opening story in his wonderful book, The Old Man and the Boy, is about a quail hunt. To the chagrin of his mother and grandmother, his grandfather, “the Old Man,” brought him a 20 gauge shotgun. They headed out into a pea field with two dogs. Quickly, the dogs were pointing and the Old Man gave him a shell and told him to load up. He broke open the barrel, slipped the shell into the breech, and snapped it closed. Then as his pulled the gun up to hold at a forty-five degree angle across his chest, to be ready for when the birds flushed, he quietly slipped the safety off and stepped toward the dogs.

Robert Ruark began quail hunting with his granddad at the age of eight. The opening story in his wonderful book, The Old Man and the Boy, is about a quail hunt. To the chagrin of his mother and grandmother, his grandfather, “the Old Man,” brought him a 20 gauge shotgun. They headed out into a pea field with two dogs. Quickly, the dogs were pointing and the Old Man gave him a shell and told him to load up. He broke open the barrel, slipped the shell into the breech, and snapped it closed. Then as his pulled the gun up to hold at a forty-five degree angle across his chest, to be ready for when the birds flushed, he quietly slipped the safety off and stepped toward the dogs. Shocked and a bit hurt, the young Robert Ruark handed his gun to his granddad, who set the safety, then headed out to the dogs. As the covey flushed, he shot a bird. When he came back, the boy yelled, “Why’d you take the gun away from me? It’s my gun. It ain’t your gun.”

Shocked and a bit hurt, the young Robert Ruark handed his gun to his granddad, who set the safety, then headed out to the dogs. As the covey flushed, he shot a bird. When he came back, the boy yelled, “Why’d you take the gun away from me? It’s my gun. It ain’t your gun.” I wonder what the Old Man would have thought about the way the Israelites hunted quail. He probably wouldn’t care for it, but I expect he would understand God’s intention of teaching the Hebrew people some good habits such as placing their trust in the Lord. The land between is a good place to learn good habits.

I wonder what the Old Man would have thought about the way the Israelites hunted quail. He probably wouldn’t care for it, but I expect he would understand God’s intention of teaching the Hebrew people some good habits such as placing their trust in the Lord. The land between is a good place to learn good habits. It’s almost as if God decides to overwhelm the Hebrew people with quail as a way to show them his power. They should have been thankful that the birds were quail and not ravens. Had it been the later, Alfred Hitchcock’s movie, “The Birds,” would could have been Biblical. But instead of the birds attacking, they are easily caught by the Israelites.

It’s almost as if God decides to overwhelm the Hebrew people with quail as a way to show them his power. They should have been thankful that the birds were quail and not ravens. Had it been the later, Alfred Hitchcock’s movie, “The Birds,” would could have been Biblical. But instead of the birds attacking, they are easily caught by the Israelites. I’ve been reading Eugene Peterson’s collection of sermons on Jeremiah, a prophet at a time when Israel was again facing some discipline. We don’t like the idea of discipline or judgment, do we? But it’s a frequent topic in scripture, probably because we (as humans) are so hard headed. Listen to what Peterson says about the topic:

I’ve been reading Eugene Peterson’s collection of sermons on Jeremiah, a prophet at a time when Israel was again facing some discipline. We don’t like the idea of discipline or judgment, do we? But it’s a frequent topic in scripture, probably because we (as humans) are so hard headed. Listen to what Peterson says about the topic: Scripture discusses judgment and discipline a lot. Some of you may think there’s too much judgment and discipline in Bible, but as Jeff Manion reminds us in his book, The Land Between, we have an advantage. As Paul wrote to Timothy, “Scripture is useful in building us up,” and if we allow Scripture to work in such a manner, we can learn from the mistakes of others.

Scripture discusses judgment and discipline a lot. Some of you may think there’s too much judgment and discipline in Bible, but as Jeff Manion reminds us in his book, The Land Between, we have an advantage. As Paul wrote to Timothy, “Scripture is useful in building us up,” and if we allow Scripture to work in such a manner, we can learn from the mistakes of others. Yesterday afternoon I was sailing in a race. There was J-105, a much larger and faster boat than any of the rest of us. This boat set the mark. We were coming back up the river, against the tide, which is a time that you try to keep your boat out of the current as much as possible. One way to do this is to hug the side of the channel where the current is less. But there’s the risk of running aground. We watched that J-105, knowing that its keel was much deeper than ours. If it had problems with shoals and ran aground (which would have been the only way we could have caught it), we would know to steer clear. Scripture is like that, we get to see the mistakes of the Israelites and the early disciples, and can steer clear of them. We can learn from their discipline!

Yesterday afternoon I was sailing in a race. There was J-105, a much larger and faster boat than any of the rest of us. This boat set the mark. We were coming back up the river, against the tide, which is a time that you try to keep your boat out of the current as much as possible. One way to do this is to hug the side of the channel where the current is less. But there’s the risk of running aground. We watched that J-105, knowing that its keel was much deeper than ours. If it had problems with shoals and ran aground (which would have been the only way we could have caught it), we would know to steer clear. Scripture is like that, we get to see the mistakes of the Israelites and the early disciples, and can steer clear of them. We can learn from their discipline! There are many Proverbs that speak of the need for discipline.

There are many Proverbs that speak of the need for discipline.

In the land between, we see that God, our Heavenly Father, disciplines his people in order for them to grow into a nation. When we are disciplined by God, we need to remember that God is loving us. God is correcting our behavior so that we might grow in our love and trust of him. Sometimes discipline is hard. I don’t know why so many people had to get sick and some of them had to die. But the God who gives us the breath of life can also take it away. But as we see, God wants his people to trust him as they are led through the desert and into the Promised Land. It’s an important lesson, for if they don’t trust him, the people will be lost. And that goes for us, too. If we don’t trust God, we are lost. Trust God; accept his discipline as a sign of love. God wants something better from us and for us. Amen.

In the land between, we see that God, our Heavenly Father, disciplines his people in order for them to grow into a nation. When we are disciplined by God, we need to remember that God is loving us. God is correcting our behavior so that we might grow in our love and trust of him. Sometimes discipline is hard. I don’t know why so many people had to get sick and some of them had to die. But the God who gives us the breath of life can also take it away. But as we see, God wants his people to trust him as they are led through the desert and into the Promised Land. It’s an important lesson, for if they don’t trust him, the people will be lost. And that goes for us, too. If we don’t trust God, we are lost. Trust God; accept his discipline as a sign of love. God wants something better from us and for us. Amen.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison We are currently working our way through the 11th chapter of the book of Numbers. Some may wonder, “why Numbers?” After all, it’s an obscure book in the Old Testament, filled with whinny, self-centered people. What could Numbers have to do with us? Well, we’re not much different. We complain, we whine, we focus on our wants and desires, as we struggle trusting God…

We are currently working our way through the 11th chapter of the book of Numbers. Some may wonder, “why Numbers?” After all, it’s an obscure book in the Old Testament, filled with whinny, self-centered people. What could Numbers have to do with us? Well, we’re not much different. We complain, we whine, we focus on our wants and desires, as we struggle trusting God… In this chapter of Numbers, the Hebrew people are in a crisis. They are in the land between, a hostile place between their former lives as slaves in Egypt and their promised future in the land of milk and honey. But they haven’t yet arrived and, in this in-between land, God forges them into a nation. They learn about temptations. In the last two weeks, we saw how it’s easy to be greedy and to complain in this land. The people’s complaints demonstrate their lack of trust in God. Moses, caught in his own land between, is being pulled apart by a grumbling people who want him to do their bidding and a God who expects him to lead the people. Although Moses also complains, he takes his complaints to God. “Believers argue with God,” I quoted last week, “skeptics argue with one another.”

In this chapter of Numbers, the Hebrew people are in a crisis. They are in the land between, a hostile place between their former lives as slaves in Egypt and their promised future in the land of milk and honey. But they haven’t yet arrived and, in this in-between land, God forges them into a nation. They learn about temptations. In the last two weeks, we saw how it’s easy to be greedy and to complain in this land. The people’s complaints demonstrate their lack of trust in God. Moses, caught in his own land between, is being pulled apart by a grumbling people who want him to do their bidding and a God who expects him to lead the people. Although Moses also complains, he takes his complaints to God. “Believers argue with God,” I quoted last week, “skeptics argue with one another.”

My first patrol leader was Gerald. He always seemed so mature even though he was probably 14 when I was 11. It rained on our first camping trip. That night Gerald gave his tent to two boys whose tent was flooded. Gerald said he would sleep in their tent. “Wow, this guy cares about us,” we thought. Of course, he was partly guilty for he suggested our tents to be lined up in a straight line and equal distance from one another. This one tent happened to be in a low spot. The next morning, Gerald was up early, helping build a fire. He was full of energy for one who had slept in a wet tent. We later learned he slept in the scout trailer which was even drier the rest of the tents.

My first patrol leader was Gerald. He always seemed so mature even though he was probably 14 when I was 11. It rained on our first camping trip. That night Gerald gave his tent to two boys whose tent was flooded. Gerald said he would sleep in their tent. “Wow, this guy cares about us,” we thought. Of course, he was partly guilty for he suggested our tents to be lined up in a straight line and equal distance from one another. This one tent happened to be in a low spot. The next morning, Gerald was up early, helping build a fire. He was full of energy for one who had slept in a wet tent. We later learned he slept in the scout trailer which was even drier the rest of the tents. In our text today, we see God answering Moses’ pleas for help. God consecrates leading men of Israel. They’ll serve essentially as patrol leaders. Moses, with only his brother Aaron to help, has become weary by attempting to take care of everyone’s needs. Moses is like a scoutmaster without patrol leaders or an army general with no junior officers and no NCOs to implement the plan. To address Moses’ weariness, God has Moses pick seventy leaders from among the people and then takes some of the Spirit that was on Moses and gives it to those seventy. A new generation of leadership is established. This is the way the scouting program works. Those in leadership positions are constantly training new ones as younger scouts slowly take on the responsibility of the troop. And it’s the way the church is to work. As new leaders are elected, they are ordained by the church with the older leaders laying their hands on the new as a sign of ordination.

In our text today, we see God answering Moses’ pleas for help. God consecrates leading men of Israel. They’ll serve essentially as patrol leaders. Moses, with only his brother Aaron to help, has become weary by attempting to take care of everyone’s needs. Moses is like a scoutmaster without patrol leaders or an army general with no junior officers and no NCOs to implement the plan. To address Moses’ weariness, God has Moses pick seventy leaders from among the people and then takes some of the Spirit that was on Moses and gives it to those seventy. A new generation of leadership is established. This is the way the scouting program works. Those in leadership positions are constantly training new ones as younger scouts slowly take on the responsibility of the troop. And it’s the way the church is to work. As new leaders are elected, they are ordained by the church with the older leaders laying their hands on the new as a sign of ordination. The people who have been complaining will also experience God’s answer to their prayer. Moses is to have them to get ready. They’re going to be eating meat! Of course, because they haven’t trusted God, they’ll eat so much meat they will get sick of it. It’ll be coming out of their nostrils, which isn’t a very pleasing picture. They had thought God had brought them into the wilderness in order that they might die, but now they’ll once again experience God’s power. God is able to answer their prayers and, in this case, will answer it in a way that they’ll wish God hadn’t.

The people who have been complaining will also experience God’s answer to their prayer. Moses is to have them to get ready. They’re going to be eating meat! Of course, because they haven’t trusted God, they’ll eat so much meat they will get sick of it. It’ll be coming out of their nostrils, which isn’t a very pleasing picture. They had thought God had brought them into the wilderness in order that they might die, but now they’ll once again experience God’s power. God is able to answer their prayers and, in this case, will answer it in a way that they’ll wish God hadn’t. You know, it’s amazing I still love peanut butter. One day, when I was in the second or third grade, I was hungry after the academic rigors of the classroom. I came home from school and went into the kitchen in search of nourishment. I spotted a large jar of peanut butter, a three pounder. It’d just been open. It was full. Seeing no one around, I unscrewed the lid and dug out a finger-full. I licked it off my finger. It was so good! Then went for another scoop. I bet none of the Scouts have every done this, have you? About the point that I had dug out a second finger full of peanut butter, my mom walked into the kitchen and yelled a few chosen words that I had not known were in her vocabulary.

You know, it’s amazing I still love peanut butter. One day, when I was in the second or third grade, I was hungry after the academic rigors of the classroom. I came home from school and went into the kitchen in search of nourishment. I spotted a large jar of peanut butter, a three pounder. It’d just been open. It was full. Seeing no one around, I unscrewed the lid and dug out a finger-full. I licked it off my finger. It was so good! Then went for another scoop. I bet none of the Scouts have every done this, have you? About the point that I had dug out a second finger full of peanut butter, my mom walked into the kitchen and yelled a few chosen words that I had not known were in her vocabulary. When we are in the land between, there are plenty of opportunities to experience and learn from God’s graciousness. This is true for our scouts and all the rest of us, for we are in the land between, often, throughout our lives. We are all on a journey to a promised land, to the promised kingdom, to the heavenly banquet. And along the way, we should learn what we can. Amen.

When we are in the land between, there are plenty of opportunities to experience and learn from God’s graciousness. This is true for our scouts and all the rest of us, for we are in the land between, often, throughout our lives. We are all on a journey to a promised land, to the promised kingdom, to the heavenly banquet. And along the way, we should learn what we can. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison Last week, we saw how the “land between” was a dangerous place. Not only are there the obvious ones. For the Hebrews in the wilderness, such dangers included thirsting, starving, or dying by snake bite. For us, the dangers may be an illness, financial ruin, the loss of a relationship, the death of a loved one. These journeys are stressful. Israel had been called into this place by God, who is trying to teach her to trust him. But what if God doesn’t show up one day? What if God doesn’t provide? Of course, because God has called them into the wilderness, they should trust the Lord. So for two years, they have been trusting God for daily food and during this time, God has not failed them. This leads to the second danger, which we saw last week, which occurs in the land between: complaint. Instead of being grateful, the Israelites become greedy. They bicker and grumble about the quality of food. Such complaints fires up God’s anger, forcing Moses to intercede.

Last week, we saw how the “land between” was a dangerous place. Not only are there the obvious ones. For the Hebrews in the wilderness, such dangers included thirsting, starving, or dying by snake bite. For us, the dangers may be an illness, financial ruin, the loss of a relationship, the death of a loved one. These journeys are stressful. Israel had been called into this place by God, who is trying to teach her to trust him. But what if God doesn’t show up one day? What if God doesn’t provide? Of course, because God has called them into the wilderness, they should trust the Lord. So for two years, they have been trusting God for daily food and during this time, God has not failed them. This leads to the second danger, which we saw last week, which occurs in the land between: complaint. Instead of being grateful, the Israelites become greedy. They bicker and grumble about the quality of food. Such complaints fires up God’s anger, forcing Moses to intercede. This week, our text focuses on Moses. He’s the leader of these bickering people. Moses is in his own “land between.” He’s caught in the middle. God is on one side and an ungrateful people on the other. It’s a lonely place. All those complaints are getting to him. He can’t please the people. God wants him to be the leader and the people just want him to do their bidding. He’s God’s servant, but the people are looking at Moses as if he’s their errand boy. 1400 years later, Jesus will remind us that we can’t serve two masters.

This week, our text focuses on Moses. He’s the leader of these bickering people. Moses is in his own “land between.” He’s caught in the middle. God is on one side and an ungrateful people on the other. It’s a lonely place. All those complaints are getting to him. He can’t please the people. God wants him to be the leader and the people just want him to do their bidding. He’s God’s servant, but the people are looking at Moses as if he’s their errand boy. 1400 years later, Jesus will remind us that we can’t serve two masters. While we are not told that Moses contemplated suicide, we do witness in today’s text that he’s ready to die. He has certainly thought about death. It seems more desirable than continuing to live in the desert where life is hard enough, but is made unbearable by a bunch of whiners. Death seems better than to live in the middle and be pulled into two different directions at the same time. Moses has had enough. I like how The Message translation handles Moses’ complaint to God:

While we are not told that Moses contemplated suicide, we do witness in today’s text that he’s ready to die. He has certainly thought about death. It seems more desirable than continuing to live in the desert where life is hard enough, but is made unbearable by a bunch of whiners. Death seems better than to live in the middle and be pulled into two different directions at the same time. Moses has had enough. I like how The Message translation handles Moses’ complaint to God: In addition to leadership being hard, often leadership is thrust upon people. Moses never asked to lead Israel out of Egypt. If you remember, he begged God to find someone else. He came up with all kind of excuses. “Lord, they’re not going to believe me.”

In addition to leadership being hard, often leadership is thrust upon people. Moses never asked to lead Israel out of Egypt. If you remember, he begged God to find someone else. He came up with all kind of excuses. “Lord, they’re not going to believe me.”