I pulled into Virginia City early in the afternoon. It was a Tuesday, the day after Labor Day, 1988, twenty-four hours after leaving Camp Sawtooth in Idaho. The summer had been idyllic, running a camp with plenty of time to hike in the mountains. Now I was heading again into uncharted territory.

The Drive from the Sawtooth Mountains to Virginia City

The previous afternoon, I’d driven from the camp to Elko on Highway 93. As I crossed the border, I was needing a place to relieve myself. However, I wasn’t sure about going into the casinos at Jackpot. I continued on, finally stopped in Elko, checking into a Motel 6. After diner, in the waning evening hours, I walked around the town watching trains run through and the sun set across the desert.

Up early the next day, I grabbed breakfast at McDonalds and hit the road. I drove west on Interstate 80, which parallels the Humboldt River across northern Nevada. Stopping for gas in Winnemucca, I noticed a tire was low. I added air and continued, but with an uneasy feeling. Earlier in the summer, I had read a book about pioneers traveling across the 40-mile desert, from the Humboldt Sink to the Washoe River. This was not a place I wanted to have a flat tire. I pulled over in Lovelock and checked the tire again. It was low and leaking. I’d picked up a nail. Thankfully in the center of the tire, so it wasn’t ruined. I found a garage who patched it in about fifteen minutes while I had lunch. Without losing much time, I was on my way.

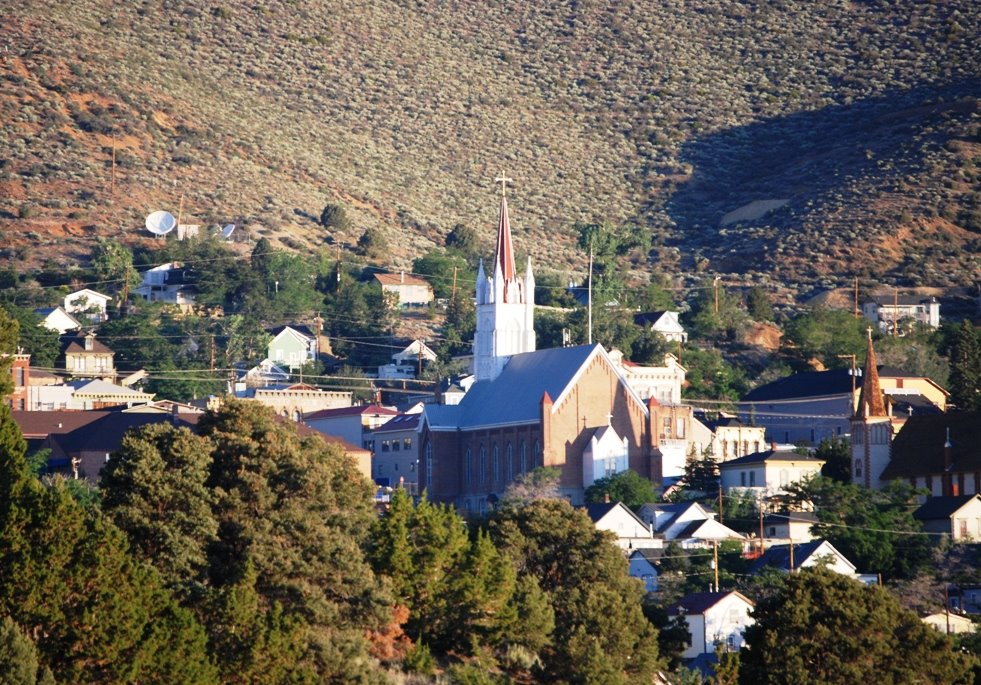

At Fernley, having crossed with 40-mile desert without realizing it, I left the interstate and took Alterative 95 south to Silver Springs. There, I turned left on Highway 50, heading toward the Sierras. The country was barren and I felt isolated. Shortly before reaching Dayton, I looked up a canyon to the northwest and glimpsed the white “V” high on Mount Davidson, my destination. At Moundhouse, where at night one could see several long red neon lights advertising legal brothels, I turned north on Nevada 341. From there, it’s a steep grade up the mountain to Virginia City.

I drove through the waning town of Silver City and squeezed through Devil’s Gate. This was a crack in a ridge barely large enough for a highway. On both sides of the strip of asphalt were relics of the past. Old headframes for mines, abandon trucks, wooden shacks, and rusty hardware. In an open pit mine, I noticed the old tunnels honeycombing the exposed side of the mountain.

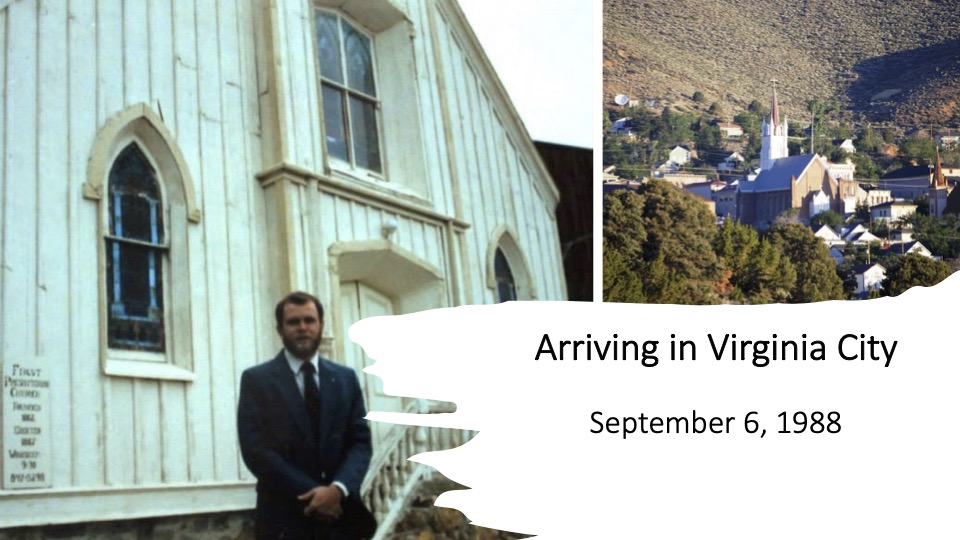

The next town was Gold Hill. From there, the road became extremely steep. I pushed the gas to the floor. My car creeped up the 13% grade that wound around a large open pit mind. Cresting at the Divide, the road dropped slightly. From here, it was known as “C Street, the main drag of Virginia City. After passing the old 4th Ward School, I pulled into a parking place in front of the old wooden church on the south end of town.

Arriving in town

The doors were locked. I was hoping someone would be there, as volunteers tried to keep it open for tourists during the summer season. I looked carefully over the 120-year-old whitewashed building, wondering what I was getting myself into. Slowly I walked around the building. The vacant lots on each side were barren, except for a few hardy weeds attempting to defy the Nevada desert. Broken bottles, bits of rusty iron, and weathered, sun-bleached, chunks of wood, all remnants of an age past where hidden under the weeds.

Afterwards, I stood for a few minutes on the front porch, leaning on the rail, looking east, down Six Mile Canyon. It would become a familiar sight with Sugarloaf, the core of an ancient volcano rising the middle of the canyon. In the distance, a couple thousand feet lower, was an alkali desert simmering under the afternoon sun which I’d just traveled through on Highway 50.

“Well, I better get on with it,” I thought, attempting to encourage myself to walk the boardwalk to the Bucket of Blood, a saloon where I had been told to pick up the keys. The sun was warm and although the peak of the tourist season was over, there were still quite a few sightseers on C Street, vying for the slot machines that stood just inside the doors of all the establishments adjacent to the boardwalk. The noise of the electronic bandits and the smell of the sausage dogs and spilt beer overwhelmed me. I lengthened my stride, sidestepping tourists, quickly covered the three blocks.

The Bucket, as it’s locally known, is a grand saloon. Except for slot machines, a 20th Century invention, it appeared little had changed since the last century when the mines produced broken men and millionaires. Chandeliers hung from the punched tin ceiling. The wooden bar was adorned with polished brass behind which hung a large mirror. Pictures of another era on the Comstock hung from the walls. I leaned against the bar and asked for Don McBride, the owner of the Bucket and husband of a member of the church.

“He’s not here,” the bartender said looking at me sideways as he washed glasses. “Are you Jeff?”

“Yeah, that’s me.”

“He told me to give you this,” as he handed me an envelope. I opened it. Onto the bar dropped a set of keys, one for the church, another for a house where I’d be staying, and a third for the post office box. There was a map, a church directory, and a sheet with names and phone numbers for people who might be of help. I returned to my car and drove to the house on B Street.

Settling in

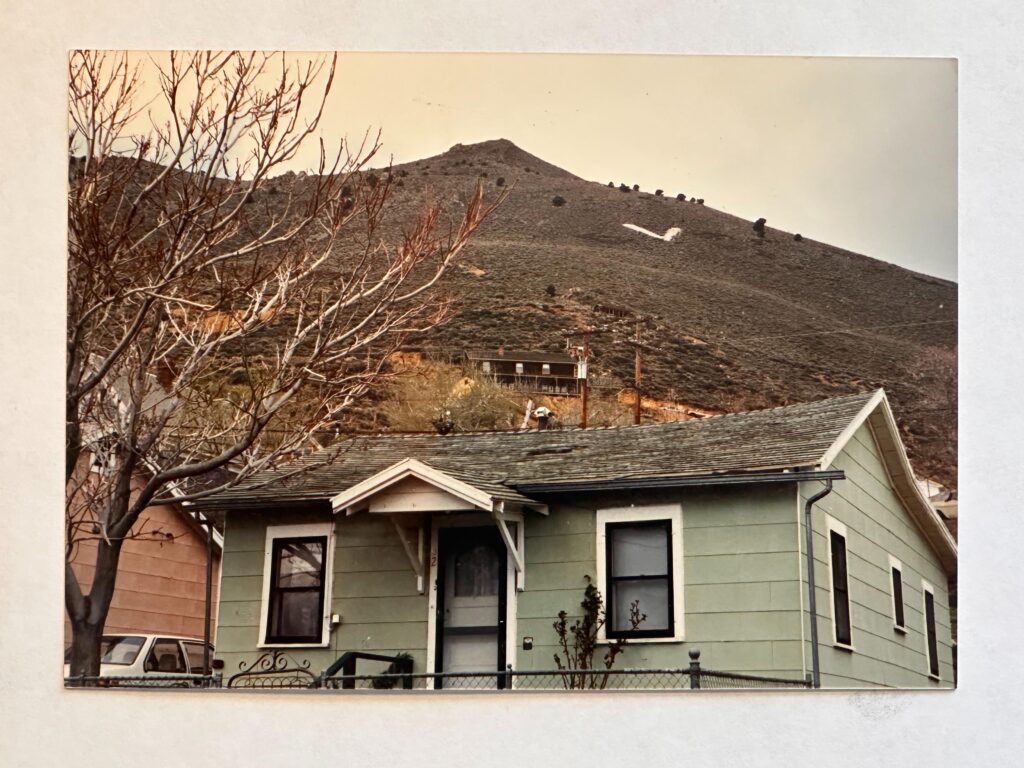

The little house the church rented for student pastors, my home for a year, was nothing to write home about. I’d been here in April, staying with Laura and David Stellman, the previous year’s student pastors. I’d flown out for the weekend to check out the position. The house had two small bedrooms, each barely large enough for a full-size bed, along with a living room, kitchen, and bathroom which sported an antique iron tub. None of the floors were level, but this is true for most of the buildings in Virginia City,. Mines held up with rotting timbers honeycomb the ground underneath the city. The earth constantly settles and occasionally sinkholes develop.

I later learned the house had an interesting history, but for now it was comfortably furnished. There was a chair, couch, coffee table, and bookcase in the living room. There was also a television, but since I never signed up for cable, it remained unused. Both bedrooms had beds. I decided to live in the front bedroom, which had a single bed and enough room for a small desk and a dresser. The bathroom was off this bedroom, and it also had a small closet. It was warm and stuffy inside. Opening the windows, the regular afternoon breezes began to blow and it was soon comfortable.

On the Formica kitchen table was a note from the women of the church, welcoming me. They also had left a few groceries. In a box was a loaf of bread, peanut butter, jelly, cooking oil, and a few cans of soup. I looked inside the refrigerator and sure enough, there was a dozen eggs, a carton of milk, some orange juice, along with a six pack of beer and a bottle of wine.

I walked out to my car and started shuttling the suitcases and boxes that I’d lived out of at camp that summer. When the car was empty, I drove back down to the church. There in a corner of the small narthex were four fruit boxes of books I’d shipped via mail on book rate, along with two larger boxes that I’d shipped via train. Howard, one of the church’s elders and a school principal in Reno had picked them up for me at the Reno station. I’d shipped these boxes in late May, which now seemed a lifetime ago. Curious as to what I’d packed, I hauled them into the house where I began to unpack.

The books quickly filled the shelves. The big boxes contained stuff for the kitchen: utensils, a wok, a coffee maker, all wrapped in dish and bath towels. There was also a light for my desk, a small fan, winter clothes, a couple of blankets, a two sets of sheets, and a few framed photos to make the house look like home.

By six o’clock, everything was unpacked. I’d even hung the pictures. As I fixed a peanut butter sandwich for dinner, I noticed the house had cooled. The sheer curtains blew in the late afternoon breeze. The sun had long set behind Mount Davison which shadowed the town to the west. The evening appeared pleasant. I ate out on the front steps. I’d been in town nearly four hours and had yet talked to anyone except the bartender. Eating my sandwich and swishing it down with a bottle of beer, I read The Peace Pilgrim.

About halfway through my meal, a man who was obviously drunk and carrying a tutu, stopped by to introduce himself. Virgil Bucchianeri said he was the district attorney. I wasn’t sure whether to believe this man holding a lacy tutu, but he was friendly and wanted to welcome me to the town. He knew I was to be the pastor at the Presbyterian Church. “I’m Catholic,” he said, “but we all get along here.” He had to run, saying he had a rehearsal of a mountain man ballet at the Piper Opera House, which was just down the street beyond the courthouse. Well, I thought to myself, if I was to wear a tutu, I’d probably be drunk, too. I finished my sandwich and picked up my book and continued to read.

Meeting Victor

A little later, another guy walked over. Victor introduced himself and said he had been attending church since moving to Virginia City from Reno a few months earlier. He invited me to go with him down to the Union Brewery. I put my book up and dropped my plate into the sink. We then walked to the bar on the north end of C Street. I learned that Victor was a relatively new attorney in Reno. Although older than me, he had left behind an academic career for law school. He had been in practice for a little over a year, choosing Nevada because it was a state without a law school. He hoped meant there would be less competition.

A few minutes later we arrived at the Union Brewery. The bar was housed in an old storefront building along C Street. It was long and narrow, rather dark, with wooden floors and plastered walls filled with photographs, bumper stickers. An artificial tree dangled from the punched tin ceiling, decorated with bras patrons had tossed up onto the branches. The bar was decidedly local, with even a sign behind the cash register that read, “Have you been rude to a tourist today?”

The Union Brewery

We entered and took our places on stools in front of the bar. The bartender brought Victor a non-alcoholic imported beer that they kept on stock for him. Victor introduced me to Julie, telling her that I was the new Presbyterian preacher. She gave me a quizzical look and asked him if I was one of his jokes. Then she asked me what I’d have. When I asked what was on tap, I learned that they made their own beer. This was long before the brewpub concept that taken off. The only homebrew beer I’d had up to this point had been bad, but I decided to try it. She nodded, twisted around, filled up a glass and plopped it in front of me. It was dark with a foamy head.

One sip, and I fell in love with the beer as I’d already fallen for the ballerina-like bartender, with her golden curves and beautiful smile. Julie wore tight fitting jeans and a half-opened shirt. In the low light she seemed angelic, dancing around, keeping everyone glass full, laughing at the jokes, and smiling at the compliments. But up close, the wrinkles around her eyes betrayed her carefree ways.

I later learned she was married to Rick, the bar owner, who made the beer in the basement. I’d have to keep my admiration to myself. As for the beer, I would later learn it was like being in a relationship with someone suffering with bipolar tendencies. Some days are great, others less so as the quality of the beer varied, depending on Rick’s temperament and sobriety. Word would get around town to avoid the latest batch and I would switch to Sierra Nevada or Anchor Steam for a week or two.

We didn’t stay very long in the bar that night. We both nursed down one drink as we got to know each other, then headed back to our places on B Street. Victor had to be in the officer early the next morning and I was exhausted from traveling and unpacking. We said our goodbyes as Victor climbed the steps up to his apartment across from the courthouse. I walked south the half block to my new home where I fell into bed.

The Next Morning

I don’t remember anything else until early the next morning when light flooded the room. Sitting on the eastern flank of Mount Davidson, Virginia City catches the first rays of the sun and they all seemed to gather in my room that morning. Having spent the summer in a narrow north-south running canyon surrounded by tall mountains, I wasn’t used to seeing the sun until late morning. Getting up, I went for a walk. It was time to check out my new home.

Other memoir pieces from this time in my life

Doug and Elvira: A Pastoral Tale

Easter Sunrise Services (a part of this article recalls Easter Sunrise Service in Virginia City in 1989)

The Revivals of A. B. Earle (an academic paper published in American Baptist Historical Society Quarterly, part of his revivals were in Virginia City in 1867)