This is another “recycled blog post” from an old blog from my journey from Indonesia to Europe taken during a sabbatical in 2011. I am concentrating on my travel blogs (mostly by train) instead of the others where I was visiting tourist sights. Here I make my way from Malaysia to Thailand.

Question: What is the largest train station ever built that never had train tracks? (answer at the end of my story)

With mixed feelings, I leave Penang behind. I have enjoyed my time here. After a couple of weeks of constant movement around Indonesia and Malaysia, it was nice to slow down for several days. The Hutton Lodge provided excellent accommodations and having Mahen, a blogger friend who lives in Georgetown, Penang, as a guide was a special treat.

Before leaving Georgetown, I spend the morning at Mahen’s clinic where I was able to see first-hand the work they do with children and young adults with cerebral palsy. I got to play with the children and watch as they work to teach a trade to the older children.

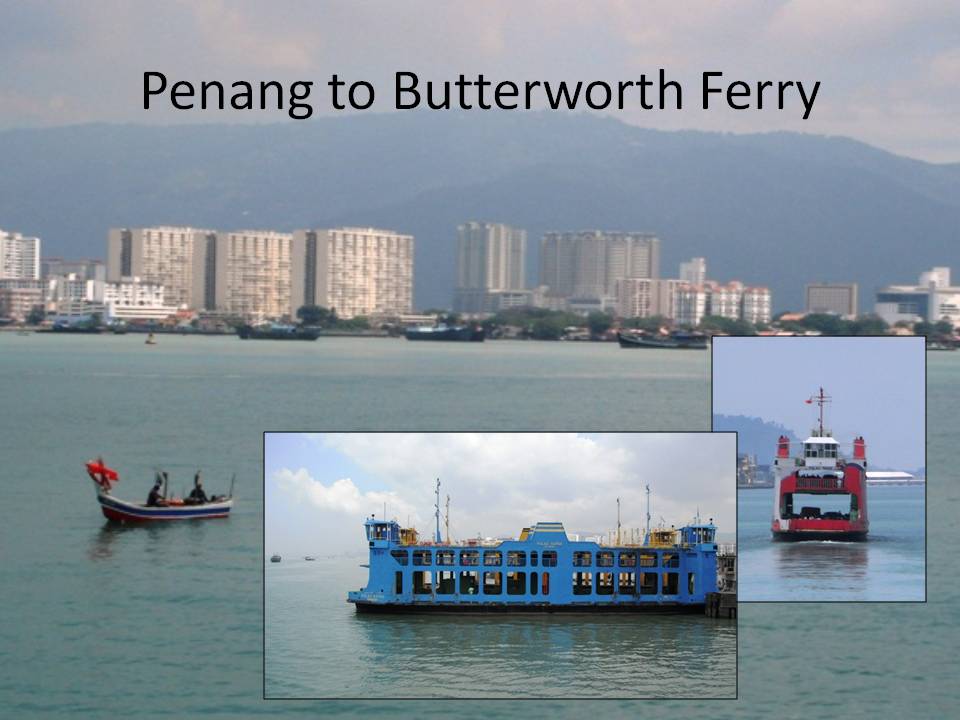

By late morning, it was time to head to the ferry. The train was scheduled for 2:20 PM, but the woman who sold me the ticket suggested I be on the ferry to cross the bay by noon. As it turned out, there was only a few minute wait for the ferry and then crossing took only 30 minutes. Once on the other side, I walked by the train station and made sure I knew where I needed to be at, then crossed the tracks and found a place for lunch. There, I talked to one of the few Americans I’d seen on the trip, a recent MBA graduate from Harvard who was traveling in Southeast Asia for a month. We chatted as we at, then we explored some old train equipment, including two old steam trains, in a park by the tracks. Coming back to the train station at 2 PM, a woman working for the Malaysian tourism asks me a bunch of questions about their tourist advertisements and what I liked about Malaysia.

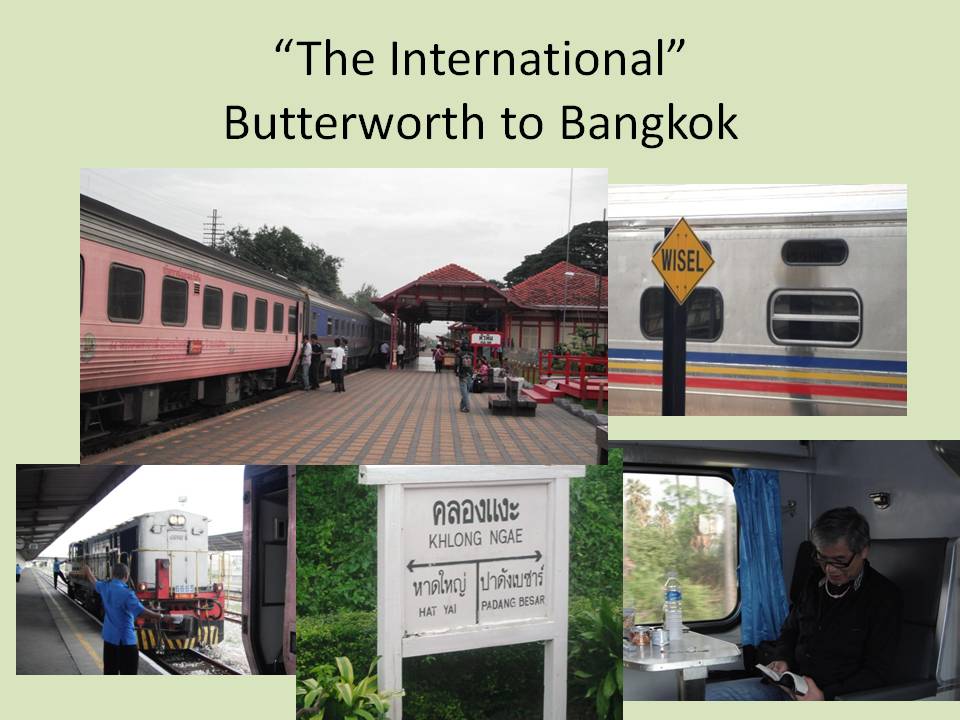

I’m shocked, when the “International” begins to load, that there are only had two cars, both second class sleepers. Even with just two cars, the train is less than half full. I’m alone in my seats, which turns into two single beds at night, with a canvas covering that provides some privacy. Sitting across the aisle as we wait to pull out of the station are two women, sisters, from Penang who were heading north for a wedding. One of them now lives in Hong Kong. We begin talking, but then the conductor informs them they are in the wrong seats and makes them move into the other car. Then, an older Indian couple boarded the train and sat in their compartment. In the seats behind me, an Australian man sits alone and we strike up a conversation.

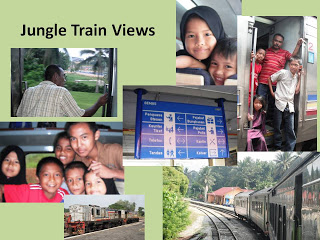

For much of the afternoon, as we head toward the Thai border, Malaysia work on upgrading their rail system (with plans that the north/south line to be fully double-tracked and electrified) is evident. New trestles are being built, tracks laid and electrical lines strung. These tracks are also a lot smoother than those tracks on Malaysia’s “Jungle Train.”

At the Thai border, we have to leave the train to clear customs. The cars continue on, but the rather plain looking Malaysian engine is replaced with a colorful Thai engine. The staff also changes. Instead of the Malay staff, we now have Thai attendants. All of them wear fancy uniforms with enough stars to create a small galaxy. A car to prepare food is also added. We check out of Malaysia, go through a gate and have our passports stamped for Thailand. The train moves forward a hundred feet or so, into Thailand, where we re-board. As we step into the car, a Thai attendant greets us with cart selling bottles of Singha beer. As a Muslim country, there had been no beer on trains in Malaysia. But now we’re in Thailand, beer is readily available.

After leaving the border, I join Allen, the man from Australia, and two Japanese men who are sitting across the aisle from Allen. We take turns buying large bottles of beer and pouring them into glasses, serving each other. The Japanese speak only broken English, but we are able to communicate. When they take orders for dinner, we all have pork, which was unavailable in Malaysia, it being a Muslim country. I have pork with noodles with oyster sauce, which was delicious.

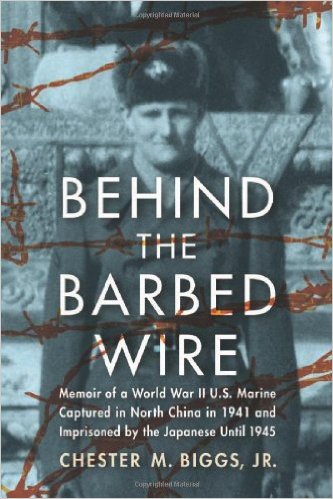

Allen and I talk through much of the evening. An Australian, he retired to Tasmania. Most of his life was spent in the military. He’d joined the British army as soon as he was eligible (his mother signed for him at 16). He was originally from Great Britain, just south of Scotland. After seeing action in Yemen and in Malaysia in the mid-1960s, he transferred to the Australian army where he spent most of his military career. He even spent a year in the United States, in the late 60s, training American Non-Commissioned Officers for jungle warfare. He served three tours in Vietnam as well as in Malaysia (there was an undeclared war between Malaysia and Indonesia on Borneo in the 60s and 70s). He’s well-read and we discussed books (we’d read many of the same), theology, government and health care, world politics, our families and the weather (it was a 23 hour train ride). Allen takes off for a few months every winter (remember, he lives in the southern hemisphere) and travels in Southeast Asia.

Allen has a lot to say about Vietnam and his experiences there. He’s critical of American forces (noting that our military is more disciplined now than then). Then, he confessed that most Australians in Vietnam didn’t like working with American units. The Australian units had jungle warfare experiences in Malaysia, and were more prepared for Vietnam. He told of once incident on his last tour in 1971. His squad had been in an ambush position for a day, waiting. He said that in the jungle it was hard to hear and to see very far and that his troops knew to wait till an enemy force was all in the killing zone (set up between two machine guns, before opening fire. If the enemy unit was too large (more than 18 men), they’d let it pass, but if smaller, they’d attack. A unit came into their trap, talking loudly. In the jungle, they couldn’t make out the words or even the language. It was assumed, because of where they were at, it was a Vietcong (VC) unit. He was also critical of the VC, saying they were no more disciplined than American soldiers. As the leader, it was his job to detonate the claymore mines as a signal for everyone to open fire. But seconds before he blew the mines, one of his machine gunners yelled, “Hold the fucking fire.” He was shocked, but the machine gunner was in position to have a good look of the last soldiers in the unit, a 6 ½ foot tall African-American. He could have been basketball player, as his head stuck up over the grass. The machine gunner realized this wasn’t a VC unit at all, and his yell saved 13 American lives.

As bad as Vietnam was, he said it didn’t compare to his short stint in Yemen with the British army early in his career. His time there makes him feel for the soldiers in Afghanistan, who are fighting a determined enemy who believes they’re on God’s side.

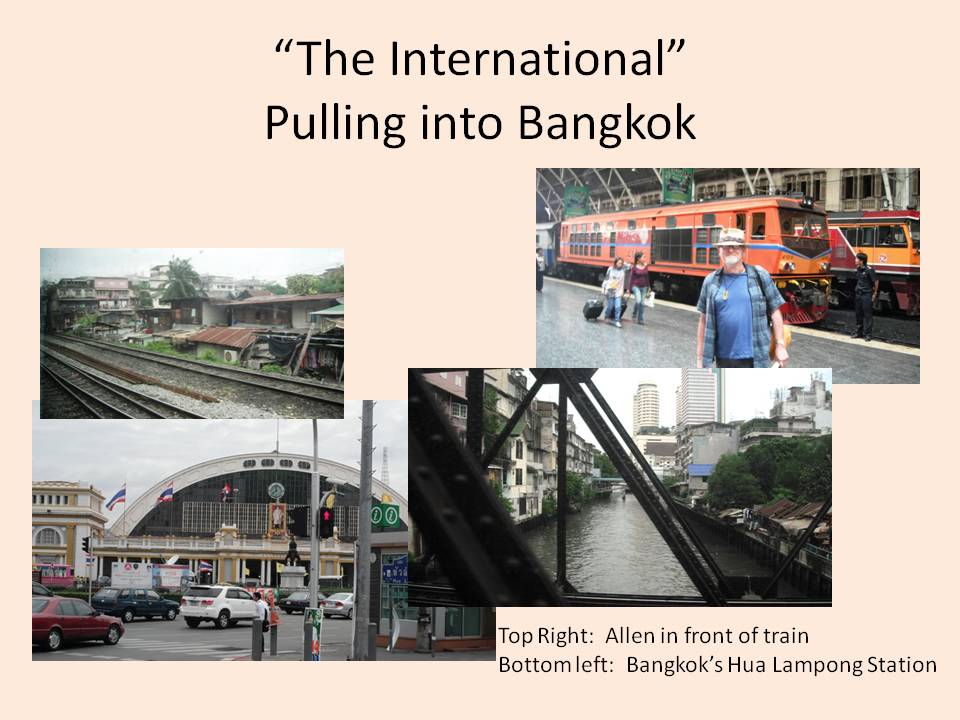

At about ten o’clock, the train attendant lowers our beds. We all head off to sleep. Across from me, the Indian couple who, especially for their age, are having a good time. The canvas covers over the sleeping areas don’t dampen the sound. Sometime in the night. after the Indian couple quiet down, , I feel the train bumping around and in the morning, there are no longer just two passenger cars, but a dozen or so. The morning also brings a different view as the mosques and minarets of Malaysia have been replaced with colorful Buddhist temples and chimneys for crematoriums of Thailand. The tracks are not as smooth as they were in Malaysia, showing their age as we pass over them.

I join Allen and the two Japanese for breakfast. For 100 baht, I get some fruit, coffee, juice and a ham sandwich. While we eat, we whisper about what must have been going on in the Indian couple’s compartment. Everyone heard them. No one is sure of their age, but we all are impressed. As we approach Bangkok, the stations become closer together and towns are larger. We pass over canal after canal, making our way on toward the city’s center, pulling into the station just a few minutes late.

At Hau Lampong, the Bangkok main train station, I say our goodbyes to my Japanese friends and Allen and I depart ways. Then I realize I am not sure where I’m going and can’t believe that I didn’t write down directions to Sam’s Lodge, where I have reservations. I find an internet café and log into my gmail account to get the directions—which are rather easy: just find the subway, go four stops and get off at Sukhumvit, leave the subway at exit three, walk to the corner and take a left… I stop to eat lunch and am at the hotel by 2 PM, where I drop my luggage off and set out to explore around Bangkok.

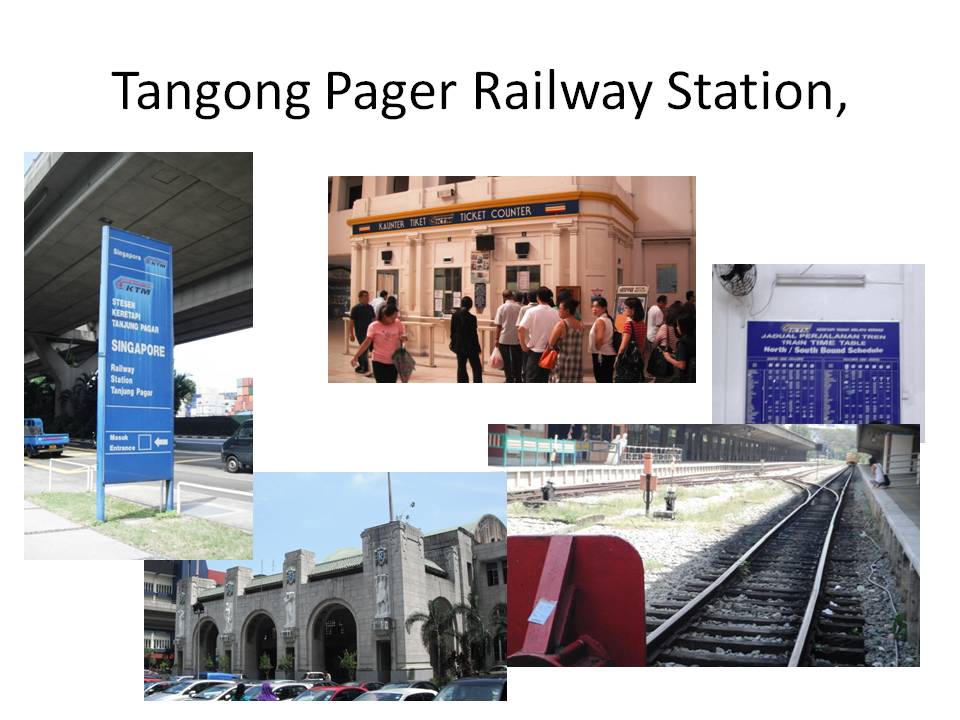

Answer: The majestic Georgetown train station on the island of Penang never had a train make it’s way to the station. The trains always ran through Butterworth, on the Malaysian mainland. But the British did a wonderful job in designing this building on the Georgetown waterfront:

Have you ever felt like you’re taking two steps forward and one step back? Sometimes life’s that way. It’s like climbing a cinder cone volcano. The ground is made of ash and is so unstable that you literally take two steps up and then slide back. You just hope to make progress. A 700-foot climb can take forever. But isn’t that how much of life is?

Have you ever felt like you’re taking two steps forward and one step back? Sometimes life’s that way. It’s like climbing a cinder cone volcano. The ground is made of ash and is so unstable that you literally take two steps up and then slide back. You just hope to make progress. A 700-foot climb can take forever. But isn’t that how much of life is?

Instead of letting the world shape our thoughts and actions, we’re to renew our minds by focusing on God. In John Ortberg’s book, the me I want to be (which I believe our Serendipity class studied a few years ago), we’re reminded of the power of a habit and how our thought patterns are as habitual as brushing our teeth.

Instead of letting the world shape our thoughts and actions, we’re to renew our minds by focusing on God. In John Ortberg’s book, the me I want to be (which I believe our Serendipity class studied a few years ago), we’re reminded of the power of a habit and how our thought patterns are as habitual as brushing our teeth. In Colossians, Paul encourages us to focus our minds on things above, not earthly things.

In Colossians, Paul encourages us to focus our minds on things above, not earthly things. Paul isn’t suggesting here that we have an instant change, that all of a sudden go from being Eeyore to Winnie the Pooh, from being a sourpuss to the life of the party, from being depressed to hopeful. We’re to “be transformed.” Transformation implies a process. We don’t create habits overnight, so we can’t recreate new and better habits overnight.

Paul isn’t suggesting here that we have an instant change, that all of a sudden go from being Eeyore to Winnie the Pooh, from being a sourpuss to the life of the party, from being depressed to hopeful. We’re to “be transformed.” Transformation implies a process. We don’t create habits overnight, so we can’t recreate new and better habits overnight. We need to embark on an effort to renew our minds. We need to drink deeply from the Scriptures as we read and study the Bible, individually and in groups. We need to ask God’s Spirit to guide, fill and help us learn to discern what God is doing in the world and how we can be a part of it. But we can’t just stop there. We’re not just to read the scriptures, we’re to “do something.” We practice living the life Jesus demonstrated. Unfortunately, as John Ortberg whom I quoted earlier, notes, we often debate doctrine and beliefs, tradition and interpretation, than do what Jesus said… “It’s easier to be smart than to be good.”

We need to embark on an effort to renew our minds. We need to drink deeply from the Scriptures as we read and study the Bible, individually and in groups. We need to ask God’s Spirit to guide, fill and help us learn to discern what God is doing in the world and how we can be a part of it. But we can’t just stop there. We’re not just to read the scriptures, we’re to “do something.” We practice living the life Jesus demonstrated. Unfortunately, as John Ortberg whom I quoted earlier, notes, we often debate doctrine and beliefs, tradition and interpretation, than do what Jesus said… “It’s easier to be smart than to be good.” We read God’s words, we learn God’s nature by discussing the Word with others, and we apply it to our lives… Read, Learn and Apply. Don’t be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds so that you may discern the will of God. Amen.

We read God’s words, we learn God’s nature by discussing the Word with others, and we apply it to our lives… Read, Learn and Apply. Don’t be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds so that you may discern the will of God. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison  In her book, Sailboat Church, Joan Gray writes: “the church’s divine nature is not always easy to see. Sometimes it takes great faith to believe that the church as we know it is the body of Christ. Sin is all too evident in our midst.” Sounds depression, doesn’t it? But Gray continues, assuring us it’s God’s way as she continues: “the church was never meant to be a group of holy people who are in themselves morally superior to everyone else.”

In her book, Sailboat Church, Joan Gray writes: “the church’s divine nature is not always easy to see. Sometimes it takes great faith to believe that the church as we know it is the body of Christ. Sin is all too evident in our midst.” Sounds depression, doesn’t it? But Gray continues, assuring us it’s God’s way as she continues: “the church was never meant to be a group of holy people who are in themselves morally superior to everyone else.” Let me say something that might be a bit controversial. Sin abounds within the church, within Christ’s body on earth. I used to think we should try to root it out, but I no longer do. Instead, maybe we should learn from the parable of the weeds and the wheat, and not risk rooting out the weeds less we also damage the wheat.

Let me say something that might be a bit controversial. Sin abounds within the church, within Christ’s body on earth. I used to think we should try to root it out, but I no longer do. Instead, maybe we should learn from the parable of the weeds and the wheat, and not risk rooting out the weeds less we also damage the wheat.

I wonder what our life of faith might look like if we, instead of referring to God as love, referred to God as compassionate. Both are correct. God is love, but in the English language, the word “love” has lost much of its power. As many of you, I’m sure, know, the Greeks had several words for love, erotic love, brotherly love, and compassionate love. We only have one word for love and apply that word too many things. We can love our spouse, our children, a sport team, a car, a sunset, good ice cream, a pair of shoes, a song on the radio… The list continues.

I wonder what our life of faith might look like if we, instead of referring to God as love, referred to God as compassionate. Both are correct. God is love, but in the English language, the word “love” has lost much of its power. As many of you, I’m sure, know, the Greeks had several words for love, erotic love, brotherly love, and compassionate love. We only have one word for love and apply that word too many things. We can love our spouse, our children, a sport team, a car, a sunset, good ice cream, a pair of shoes, a song on the radio… The list continues. It’s often pointed out that “love” should be a verb. It should lead us to action toward that for which we have affection. It’s not just a static or emotional feeling, but is something that manifested itself in action for the wellbeing of the other. In that way, it’s like compassion, being moved to work for the benefit of the other. God is compassionate as shown in sending us his Son, to offer the human race a chance to free itself from the muck which keep us stuck and bogged down in sin. Those of us who have experienced this compassion from God are to show such compassion to others.

It’s often pointed out that “love” should be a verb. It should lead us to action toward that for which we have affection. It’s not just a static or emotional feeling, but is something that manifested itself in action for the wellbeing of the other. In that way, it’s like compassion, being moved to work for the benefit of the other. God is compassionate as shown in sending us his Son, to offer the human race a chance to free itself from the muck which keep us stuck and bogged down in sin. Those of us who have experienced this compassion from God are to show such compassion to others. The word compassion, in English, implies an awareness of another’s distress, with a desire to help alleviate that distress in some manner. It has a deeper theological meaning, as it is linked to God’s actions. In the New Testament, the word compassion is used to describe Jesus or, used by Jesus to refer to God. Paul is the one who makes the link between the compassion of God, as we see in revelation of God in Jesus Christ, to our own call to be compassionate.

The word compassion, in English, implies an awareness of another’s distress, with a desire to help alleviate that distress in some manner. It has a deeper theological meaning, as it is linked to God’s actions. In the New Testament, the word compassion is used to describe Jesus or, used by Jesus to refer to God. Paul is the one who makes the link between the compassion of God, as we see in revelation of God in Jesus Christ, to our own call to be compassionate. A modern writer defines compassion as “the knowledge that there can never really be any peace and joy for me until there is peace and joy finally for you too.”

A modern writer defines compassion as “the knowledge that there can never really be any peace and joy for me until there is peace and joy finally for you too.” Paul begins this section of his letter to the Philippians with a series of “if” clauses. This repetitiveness is tricky to translate, for we often use “if” to imply a dream. “If only this was real.” “If only this had happened…” But Paul’s use of the conditional cause doesn’t demonstrate a lack of certainty. Paul uses this litany of clauses to drive home a point. “If you believe this and if it’s made a difference in your life as it has in mine, then do this!” “If you have gotten anything out of following Christ, being in his Spirit-filled community, if you have a heart or an ounce of care, then you should act in this way.” Verse one is the lead up to how we should live as disciples, which is covered in verses 2 – 5.

Paul begins this section of his letter to the Philippians with a series of “if” clauses. This repetitiveness is tricky to translate, for we often use “if” to imply a dream. “If only this was real.” “If only this had happened…” But Paul’s use of the conditional cause doesn’t demonstrate a lack of certainty. Paul uses this litany of clauses to drive home a point. “If you believe this and if it’s made a difference in your life as it has in mine, then do this!” “If you have gotten anything out of following Christ, being in his Spirit-filled community, if you have a heart or an ounce of care, then you should act in this way.” Verse one is the lead up to how we should live as disciples, which is covered in verses 2 – 5. I love (there’s that word again) how The Message translates verse four: “Forget yourself long enough to lend a helping hand.” Paul’s talking about compassion. And then he drives this home as he tells us to be like Christ, the compassionate one. Starting with verse sixth, Paul appears to be quoting an early church hymn about Christ and he encourages us to imitate Christ’s compassion and humility. Instead of pushing and shoving and demanding that we get our “fair-share,” we’re to be Christ-like which means we lower ourselves in order to help others. In difficult situations, humility helps de-escalate tension.

I love (there’s that word again) how The Message translates verse four: “Forget yourself long enough to lend a helping hand.” Paul’s talking about compassion. And then he drives this home as he tells us to be like Christ, the compassionate one. Starting with verse sixth, Paul appears to be quoting an early church hymn about Christ and he encourages us to imitate Christ’s compassion and humility. Instead of pushing and shoving and demanding that we get our “fair-share,” we’re to be Christ-like which means we lower ourselves in order to help others. In difficult situations, humility helps de-escalate tension. You know, our lives tell a story. Whether we like it or not, how we live, what we care for, how we treat others, where we invest our talents and money, all combine to tell our story. As followers of Christ, our story will either compel others to check out our faith or it will repel them. If we realize this, it’s important that we strive to live in a way that will honor Jesus and show our trust in the Almighty. And that means to live compassionately. As one writer commented on this, “It’s not wise to name yourself as a Christian unless you are actually embodying the way of Messiah Jesus.”

You know, our lives tell a story. Whether we like it or not, how we live, what we care for, how we treat others, where we invest our talents and money, all combine to tell our story. As followers of Christ, our story will either compel others to check out our faith or it will repel them. If we realize this, it’s important that we strive to live in a way that will honor Jesus and show our trust in the Almighty. And that means to live compassionately. As one writer commented on this, “It’s not wise to name yourself as a Christian unless you are actually embodying the way of Messiah Jesus.” How might we be compassionate? We can look at the life of Jesus and live as he did? Or we might think of some of our contemporaries. Since last Sunday, we have lost a good one, a compassionate man. Jim Fendig was humble and soft spoken and concerned for others. And there are others like him within our community.

How might we be compassionate? We can look at the life of Jesus and live as he did? Or we might think of some of our contemporaries. Since last Sunday, we have lost a good one, a compassionate man. Jim Fendig was humble and soft spoken and concerned for others. And there are others like him within our community.

Are we like that? Are we closed to the possibilities of what God might do through us? Are we resistant to the abilities of Almighty God, who can do more than can imagine? Perhaps, like the man in the story, we want to keep God hidden, focusing on ourselves, even though we don’t (by ourselves) have the ability to do miracles? But, you know, when we don’t care who gets the credit, great things can happen. And if it is happening with God, even greater things can happen.

Are we like that? Are we closed to the possibilities of what God might do through us? Are we resistant to the abilities of Almighty God, who can do more than can imagine? Perhaps, like the man in the story, we want to keep God hidden, focusing on ourselves, even though we don’t (by ourselves) have the ability to do miracles? But, you know, when we don’t care who gets the credit, great things can happen. And if it is happening with God, even greater things can happen.

Our reading from the Apostle Paul’s letter to the church in Ephesus is a prayer. Paul prays his brothers and sisters in Ephesus will find strength in God’s spirit and that Christ might dwell in their hearts through faith rooted and grounded in love.

Our reading from the Apostle Paul’s letter to the church in Ephesus is a prayer. Paul prays his brothers and sisters in Ephesus will find strength in God’s spirit and that Christ might dwell in their hearts through faith rooted and grounded in love. By the way, this isn’t the only place where Paul emphasizes the importance of love. Yesterday, in the Men’s Saturday morning Bible Study, we looked at 1 Corinthians 13, which is known as the love chapter. There, Paul is insisting that the various factions within the Corinthian Church love one another. God loves us, as shown in Jesus Christ, and we are to love one another. It’s as simple as that. Even Sigmund Freud, who isn’t known for his Christian sympathies, said that we must love in order that we will not fall, and if we can’t love, illness will take over us.

By the way, this isn’t the only place where Paul emphasizes the importance of love. Yesterday, in the Men’s Saturday morning Bible Study, we looked at 1 Corinthians 13, which is known as the love chapter. There, Paul is insisting that the various factions within the Corinthian Church love one another. God loves us, as shown in Jesus Christ, and we are to love one another. It’s as simple as that. Even Sigmund Freud, who isn’t known for his Christian sympathies, said that we must love in order that we will not fall, and if we can’t love, illness will take over us.

Maybe we, as Christians, need to do more daydreaming about what it means to be the people of God. That’s what this four week study is about. God has endowed in us an ability to image new worlds. But are we willing to join with God in creating them? Or do we limit God by our own lack of imagination. We need to free God to work miracles in our lives, within our congregation and community and within our world. If we trust God, and ground ourselves in agape love, which is the type of love that calls us to work for the best of others, there’s no limit to what might be accomplished. If we trust in God’s power and are willing to creatively join God in working for a better world, there is no telling what might come out of our efforts. But if we act like things depend on what we can do and have no imagination, we risk a dark dystopia future.

Maybe we, as Christians, need to do more daydreaming about what it means to be the people of God. That’s what this four week study is about. God has endowed in us an ability to image new worlds. But are we willing to join with God in creating them? Or do we limit God by our own lack of imagination. We need to free God to work miracles in our lives, within our congregation and community and within our world. If we trust God, and ground ourselves in agape love, which is the type of love that calls us to work for the best of others, there’s no limit to what might be accomplished. If we trust in God’s power and are willing to creatively join God in working for a better world, there is no telling what might come out of our efforts. But if we act like things depend on what we can do and have no imagination, we risk a dark dystopia future.

The Israelites in exile were told to seek the wellbeing of the community in which they were living and we’re to do the same.

The Israelites in exile were told to seek the wellbeing of the community in which they were living and we’re to do the same.

Few ponder freedom more than those in prison with long days and nothing to do. Although few succeed, some spend their time creatively, attempting to obtain freedom. There were these two dudes at the Texas Correction Facility in Huntsville, who planned and watched and finally figured out if they could just crawl into the back of a delivery truck, they could possibly make it out. From observations, they learned there was this one truck that wasn’t checked as thoroughly as others. They jumped in the back, hoping they weren’t seen. Soon, the truck was beyond the walls of the prison and rolling down the highway. They waited until the truck stopped and parked. They slipped out. To their horror, this discovered they were inside the walls of another Texas prison.

Few ponder freedom more than those in prison with long days and nothing to do. Although few succeed, some spend their time creatively, attempting to obtain freedom. There were these two dudes at the Texas Correction Facility in Huntsville, who planned and watched and finally figured out if they could just crawl into the back of a delivery truck, they could possibly make it out. From observations, they learned there was this one truck that wasn’t checked as thoroughly as others. They jumped in the back, hoping they weren’t seen. Soon, the truck was beyond the walls of the prison and rolling down the highway. They waited until the truck stopped and parked. They slipped out. To their horror, this discovered they were inside the walls of another Texas prison.

Our passage begins with Jesus in the presence of some folks who had believed in him.

Our passage begins with Jesus in the presence of some folks who had believed in him.

Of course, Jesus is not speaking of political or physical freedom. And those who are listening don’t understand this. He’s using the word metaphorically, to show the power of sin to control and enslave us. In order to redirect their focus, Jesus tells them that everyone who sins is a slave to sin!

Of course, Jesus is not speaking of political or physical freedom. And those who are listening don’t understand this. He’s using the word metaphorically, to show the power of sin to control and enslave us. In order to redirect their focus, Jesus tells them that everyone who sins is a slave to sin!

Jesus tries to get people to see beyond their own self-interest by shattering our reality. He represents the truth which is not bound by anything in our material world. Jesus represents a greater reality, but can we accept him? If we accept him and live as if he is the most important thing, those things that ensnare us and entrap us may still be a threat, but they no longer have any power. If we accept Jesus and hang with him, we know that whatever happens to us, in life and in death is going to be okay for we belong to Jesus Christ.

Jesus tries to get people to see beyond their own self-interest by shattering our reality. He represents the truth which is not bound by anything in our material world. Jesus represents a greater reality, but can we accept him? If we accept him and live as if he is the most important thing, those things that ensnare us and entrap us may still be a threat, but they no longer have any power. If we accept Jesus and hang with him, we know that whatever happens to us, in life and in death is going to be okay for we belong to Jesus Christ. You know, if we accept Jesus into our lives, we must still pay the bills, go to work, and take out the trash. After all, God created us for work. It’s important that we do what we can to earn our daily bread and to offer up our labors for God to bless. Doing so, we’re freed from thinking what really matters are those things we worry about day in and day out. In the grand scheme of things, they don’t matter. We’re freed from looking out upon the world and seeing it as something to be conquered or earned. That’s not Biblical. Instead, we’re free to look out upon the world and accept it as a gift from a gracious God. And most importantly, we’re free from the guilt and shame of our past. Sin no longer eats at us because we’ve been accepted by Jesus. And, unlike our freedom, Jesus’ offer is something no one can take away.

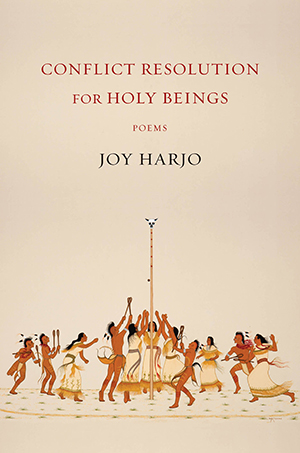

You know, if we accept Jesus into our lives, we must still pay the bills, go to work, and take out the trash. After all, God created us for work. It’s important that we do what we can to earn our daily bread and to offer up our labors for God to bless. Doing so, we’re freed from thinking what really matters are those things we worry about day in and day out. In the grand scheme of things, they don’t matter. We’re freed from looking out upon the world and seeing it as something to be conquered or earned. That’s not Biblical. Instead, we’re free to look out upon the world and accept it as a gift from a gracious God. And most importantly, we’re free from the guilt and shame of our past. Sin no longer eats at us because we’ve been accepted by Jesus. And, unlike our freedom, Jesus’ offer is something no one can take away. I picked up this book after learning that Joy Harjo has been appointed poet laureate for the United States. It’s exciting because she’s the first Native American to serve in this position. In addition to being a poet, Harjo is also a jazz musician. Her poetry blends music with longing for a home that seems evasive. In different poems, the reader is taken an “Indian school” in Oklahoma, to the hunting grounds of the Inuit people in northern Alaska, and through airports and other locals in between. She alternates between more free-form poetry to “prose poems.” Many of the poems draw the reader into the experience of modern Native Americans, who, having lost a homeland, are not sure where they belong. We also are reminded of the realities within Native communities of alcoholism and suicide. Yet, a thread of hope weaves through these poems, as we (as well as all creation) are encouraged to be blessing to others. I find her poems accessible and easy to understand. I’m sure I will reread many of them as I continue to ponder their messages. .

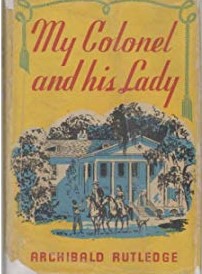

I picked up this book after learning that Joy Harjo has been appointed poet laureate for the United States. It’s exciting because she’s the first Native American to serve in this position. In addition to being a poet, Harjo is also a jazz musician. Her poetry blends music with longing for a home that seems evasive. In different poems, the reader is taken an “Indian school” in Oklahoma, to the hunting grounds of the Inuit people in northern Alaska, and through airports and other locals in between. She alternates between more free-form poetry to “prose poems.” Many of the poems draw the reader into the experience of modern Native Americans, who, having lost a homeland, are not sure where they belong. We also are reminded of the realities within Native communities of alcoholism and suicide. Yet, a thread of hope weaves through these poems, as we (as well as all creation) are encouraged to be blessing to others. I find her poems accessible and easy to understand. I’m sure I will reread many of them as I continue to ponder their messages. . In this short book, the former poet laureate of South Carolina, Archibald Rutledge, writes a memoir of his parents. His father had been the youngest colonel in the Confederate army. His father joined the war in North Carolina (the family kept a mountain home to escape to in the summer). He was wounded three times, involved in many engagements and served as best man for General Pickett, when he married. Archibald was the youngest child of the family (for which, his father often called him Benjamin, for Jacob’s last son). He was born in 1883, nearly twenty years after his father’s military experience had ended. Rutledge was in awe of his father, whom he saw as a kind, gentle, and loving man. His father shared with him the love of all things wild-hunting and fishing and just walking in the woods. He also shared his love of the creator whom he saw revealed in nature. His mother, the colonel’s lady, was also a kind but strong woman. As her husband was often away, she had to take control as she did directing the successful efforts at fighting a fire in the great house (when water had to be drawn from the river by buckets) and shooting to scare away intruders who were looking to steal from their rice barn. She also impressed the young Rutledge with her love of books and her care of others (she often served as a medical resource in a community that often had to go without physicians).

In this short book, the former poet laureate of South Carolina, Archibald Rutledge, writes a memoir of his parents. His father had been the youngest colonel in the Confederate army. His father joined the war in North Carolina (the family kept a mountain home to escape to in the summer). He was wounded three times, involved in many engagements and served as best man for General Pickett, when he married. Archibald was the youngest child of the family (for which, his father often called him Benjamin, for Jacob’s last son). He was born in 1883, nearly twenty years after his father’s military experience had ended. Rutledge was in awe of his father, whom he saw as a kind, gentle, and loving man. His father shared with him the love of all things wild-hunting and fishing and just walking in the woods. He also shared his love of the creator whom he saw revealed in nature. His mother, the colonel’s lady, was also a kind but strong woman. As her husband was often away, she had to take control as she did directing the successful efforts at fighting a fire in the great house (when water had to be drawn from the river by buckets) and shooting to scare away intruders who were looking to steal from their rice barn. She also impressed the young Rutledge with her love of books and her care of others (she often served as a medical resource in a community that often had to go without physicians).