I started this post two weeks ago, when I was in Detour Village in Michigan’s UP. Today, I am in Wilmington, NC, , as my father is recovering from four bowel surgeries… I know this is a long post. If you find what I say about one author boring, just skip to the next. In a way, this massive data dump is my way of summarizing what’s in my journal. I placed photos of the books which I came away with from the festival.

Pre-Conference Workshop on Wednesday

Northern Red Oak

“I am the vine, you are the branches,” Jesus said.

“Cut off from me you can do nothing.”

Yet, the heavy oak branch,

sheared from its life source,

fallen from the empyrean,

decomposes slowly on the forest floor

in a bed of rotten leaves

from which trout lilies sprout.

Wednesday at the Festival

I scratched out the above poem in a workshop by Paul Willis, a poet I first met at the festival nearly 20 years ago. He gathered us into groups of four and set us free in the nature preserve behind the Prince Conference Center at Calvin University. We were to quietly make our way through the preserve, taking turns leading and then pointing out something of interest. We would each make notes, and another person would lead the group. After 45 of so minutes of silence, we discussed what we saw. Then he gave us just a few minutes to take one of the things we’d written about and to create a poem. Hence, the poem I wrote about a large branch of an oak tree resting on the forest floor.

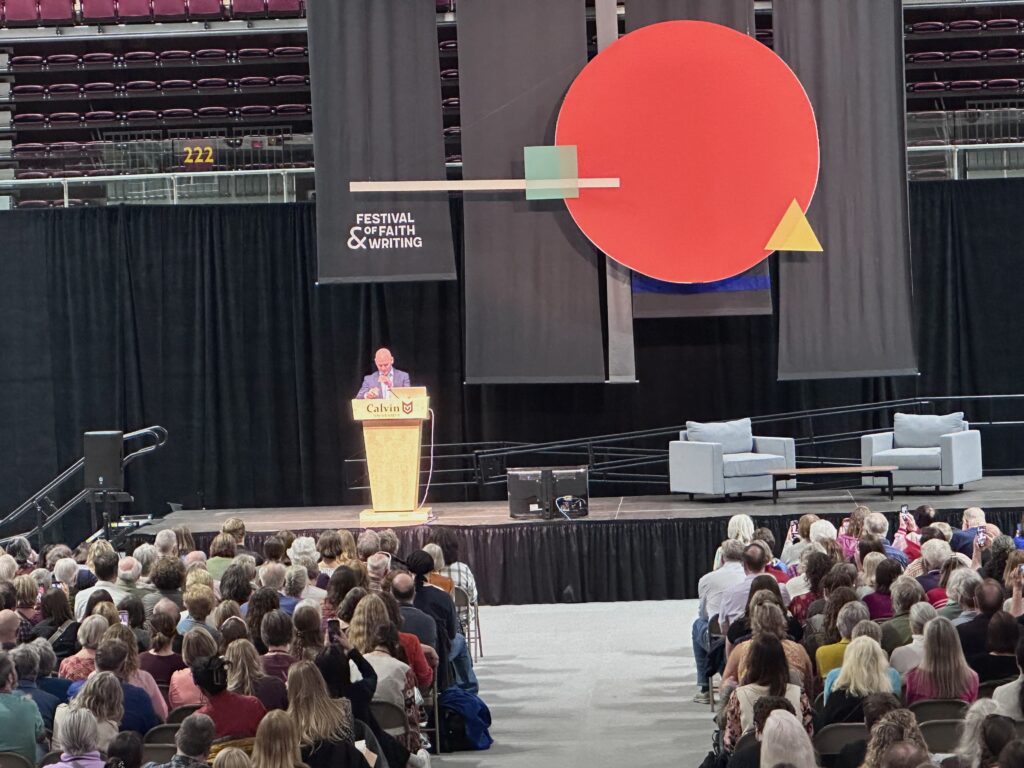

After seeing the eclipse in South Charleston, Ohio on April 8, I attended the Calvin Festival of Faith and Writing. This is my fifth time at this festival, which is held every other year. The last festival I attended was in 2012. And, because of COVID, this year’s festival is the first in-person gathering since 2018. Over the years I have heard a many great authors speak about writing and faith including Salman Rushdie, Wally Lamb, Scott Russell Sanders, Eugene Peterson, Kathleen Dean Moore, Thomas Lynch, Parker Palmer, Mary Karr, Debra Dean, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Craig Barnes, and Ann Lamott. Each year, the festival draws in around sixty authors and a couple thousand participants. While almost all the authors are Christians, the only requirement is that they write about faith. In addition to Christian authors, there have been Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and even atheists.

Here are the authors I heard. There’s no way one can hear all the authors in three days. I tried to capture a bit of what I learned from them. I have listed the authors in order that I first heard them at the conference (in some cases I heard them speak twice):

Thursday at the Festival

Margaret Feinberg is a podcaster (The Joycast) and author of Scouting the Divine: Fight Back with Joy, Taste, a See. Feinberg spoke on sustaining a writing life. She detailed two practices and drew from her own life and her book for examples:

- Cultivate a life of Adventure (or live a compelling life). She drew on her parents’ examples as well as on those who grow grapes.

- Cultivate a life of healing. Here, she drew on the work of olive growers.

Ruth Graham Born in an evangelical family, Graham now serves as a religious writer for the New York Times. Thankfully, she noted, the job of a religious reporter today isn’t focused on denominational meetings. She’s more interested in getting to the heartbeat of religious experiences. She told of a story she wrote for Slate, about a man from Dalton, Georgia, whose Bible leaked oil. She tried to tell the story, which she suggested was about a man who had a religious experience which got out of hand, in a way that is fair to all sides.

Sara Horwitz Born in a secular Jewish family, Horwitz rediscovered the faith of her ancestors in her mid-30s working in the Obama White House. She first was on a team of writers for the President, and later became the speech writer for Michelle Obama, the first lady. Horwitz spoke about how encouraging everyone in the White House was to her desire to practice her faith (including turning off her cell phone on the Sabbath). She gave up an opportunity to help Michelle Obama with her memoir to write a book on her journey into Judaism. Religion, she said, should draw us out from ourselves and into something larger. She found freedom in the Jewish law which she interprets as a system of maintaining dignity in others.

Marilyn McEntyre A popular podcaster and Bible teacher, Feinberg titled her talk, “Writing Through a Fog of Fear: Finding Life, Giving Words in an Alarming Time.” Acknowledging the challenges facing writers today, she spoke of our context while providing questions for discernment and strategies for publicly presenting our work. She began with two epitaphs: “Be not afraid,” -Jesus. And “Be afraid, very afraid.” -Mel Brooks.

Discerning questions:

From where does my energy or sense of urgency come?

- Who would I most like to read this? If only one reader, who?

- Who will take offense or be troubled? How can I address their concerns?

- In writing this, what does it mean to me to be as wise as serpents and innocent as doves?

- We bring our own association to every word. But the same works for others. What words of ours will be their triggers?

Strategies for speaking into fear:

- Study your favorite risk takers (suggest reading Gaza Writes Back)

- Have meta-conversations where you can. Talk about language behind our words to help people better connect.

- Listen to the call of the moment.

- What does it mean to be faithful? Do you put a name to what you are faithful to?

- You don’t have to go into anger. You can model debate, hope. Let your style be modelling.

- Be responsible to speak to the complication of the issue. What do we want people to hear? Honor complexity of beliefs.

- Don’t under-estimate the power of beauty.

- Be surprising. Change up our writings with exhortation, humor, lament in the same piece.

- Change genres. Try out new genres.

- Offer authentic antidotes. Try following Jesus’ example and speak into issues.

- Stories are important. Stories help disarm.

- Acknowledge the emotional weight (Susan Sontag writing on the pain of others)

- Play with paradox. Be a gentle alarmist, a light-hearted doomsayer.

- Be a prophetic trickster, a Riddler.

- When you have the privilege from writing with safety, remember those being killed for their speech. We can speak because they can’t.

- Write with others.

- Pray for clarity, for when and to whom to write, for obedience, courage, and passion.

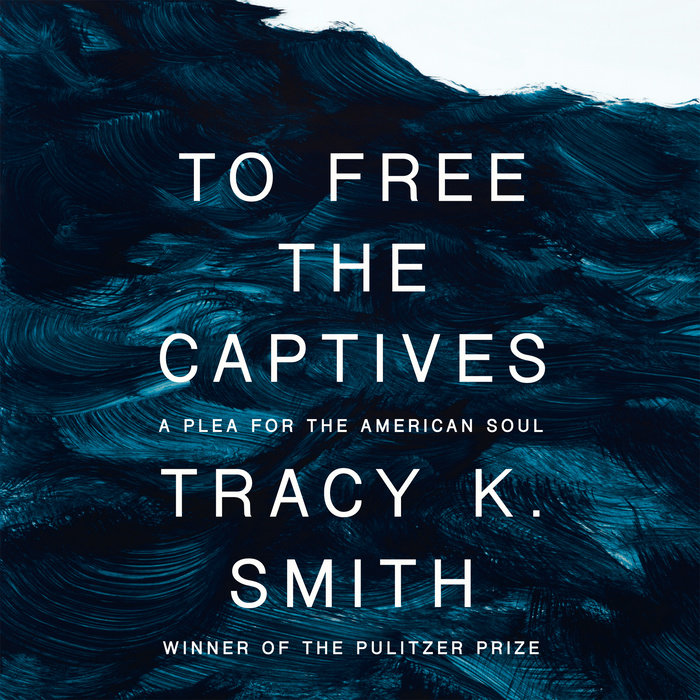

Tracy Smith (keynote). Smith provided the Thursday night keynote address. A graduate of Harvard and Columbia, she also was a Stenger Fellow at Stanford. She has served as nation’s poet laurate (2017-2019), has been awarded the Pulitzer-Prize and has published poetry, a memoir, and non-fiction. Currently, she teaches at Harvard, and has recently published To Free the Captives: A Plea for the American Soul.

Her speak focused on reading certain poems and reflecting on how they came about and how they might be interpreted. In her introduction, her work was described like “Jacob wrestling with God” and how our “paradoxical wounds can heal.” The poems she read and reflected on included: “Hill Country,” Weather in Space,” “We all Go Chasing All We Will Lose,” “Political Poem,” “The United States Welcomes You,” “The Fright of our Shared History,” and “Wade in the Water.”

Sadly, all her books of poetry had sold out, but I came away with a signed copy of To Free the Captives and look forward to exploring her vision of a better world.

Friday at the Festival:

Mary DeMuth spoke on “stories as healing.” Telling the truth, she proclaimed, is the key too both good writing and good living. She provided six things to consider if we fear sharing a story:

- Discern timing. “Don’t vomit on the reader.” A story never told can never heal, but we should remember that our call is to first write, not necessarily publish.

- Exactness is not the same as truth. We must remember that it is our story and no one else can tell the story in the same way as we can. Storytelling is an effective truth delivery vehicle.

- Expect opposition. While we should welcome helpful feedback, we also take a risk of putting our work out there. Sometimes, when you tell the truth, you engage is spiritual warfare. She finds having a prayer team helpful as they both pray against attacks but also help keep her humble.

- Name our fear.

- Expose evil but love your readers.

- See the benefits (God gives us glory in our weakness).

If we don’t tell the truth, we misrepresent people. Our job is not to enlarge villains but to enlarge Jesus.

Matthew Dickerson and Fred Bahnson titled their conversation, “Ecology Imagination and why stories matter.” Dickerson part of the conversation was often based on Tolkien. I haven’t read Tolkien since college. Bahnson (I’ve read his book Soil and Sacrament), drew more from Wendell Berry and Barry Lopez, two authors I continue to read. Bahnson described how the richest life is found where rivers meet oceans, and how writers need to put themselves in such uncomfortable and risky settings to best flourish.

Diane Mehtu spoke about Dante and Virgil (Dante’s guide through hell). This was a fascination lecture even though the presenter read from a paper. She uses powerful language. She presented the idea of the friendship of the two poets, who lived over a Millenia apart, and what she’s learned from repeatedly reading the Divine Comedy. What made the lecture even more interesting to me is that I had been listening to an unabridged reading of Augustine’s City of God and had just heard Augustine dealing with Virgil.

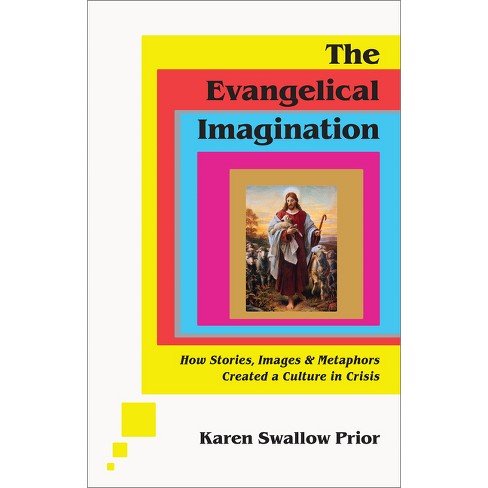

Karen Swallow Prior titled the lecture I attended, “Imagination: It’s not just Hobbits and Hobby Horses.” She questioned how we often consider imagination as something playful within our childhood and mostly individualist. This she challenged, suggesting that we often inherit language structures (language is based on imagination) without understanding how it came about. This she applied to evangelicalism, of which she was critiquing and suggests needs to embrace imagination to work its way out of its crisis. Another criticism of evangelism is that it tends to draw more on American ideals than the Christian faith and is a product of modernity and late-stage capitalism. She also critiqued evangelism’s emphasis on the end times, suggesting that we don’t need stories about the end but about how to get there. The early Christians, who called themselves “people of the way” understood this.

Yaa Gyasi (Friday evening keynote) This “conversation” between Gyasi and Jane Zwart focused on her two novels and how they deal with grief and loss. Gyasi was born in Ghana, but grew up in Huntsville, Alabama. Her experiences seem to provide her a unique perspective even though I haven’t read her books. Quote: “Prayer and writing comes from the same place. From your pen to God’s ear.”

Saturday at the Festival

Christian Wiman is a professor of communication arts at Yale Divinity School (and former editor of Poetry). I attended his lecture titled “The Art of Faith, The Faith of Art.” Wiman read several of his poems and reflected on the faith and art within them. Sadly, I was running late and missed part of this lecture.

Danielle Chapman I heard Chapman speak twice. The first session was a discussion with Jim Dahlman on Southern literature. While both have published books which I came away with, I questioned their representation as a Southern writer. But her poetry is engaging as is her memoir, which I have already started and will review.

I later heard her talk on memory in non-fiction and poetry.

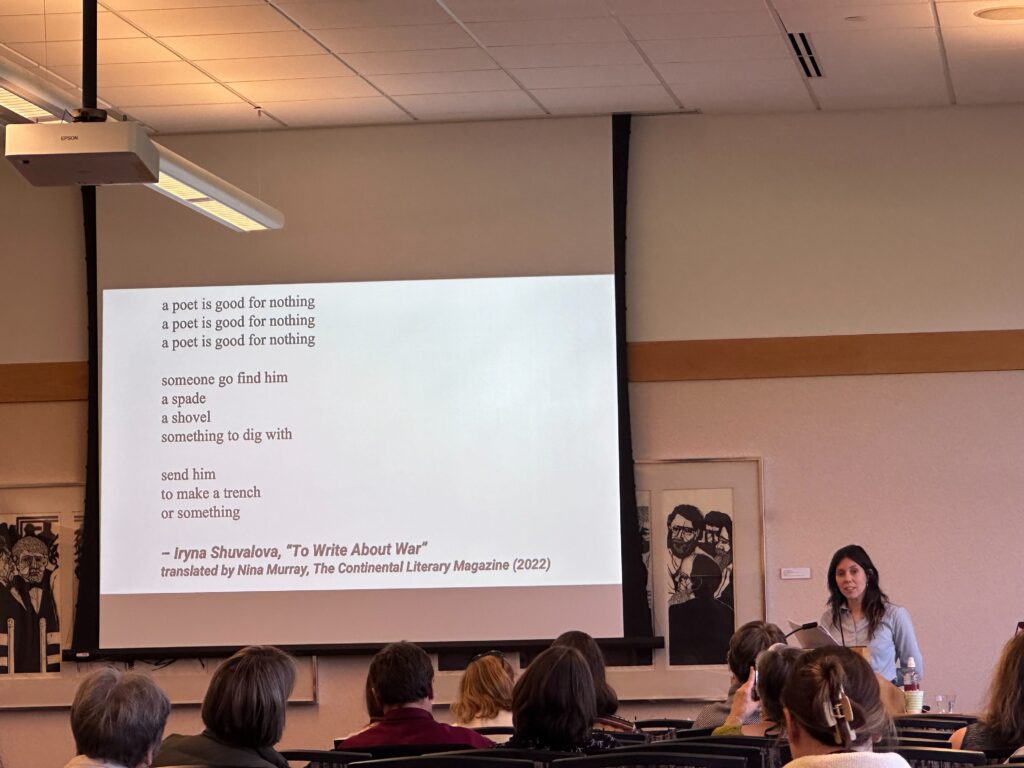

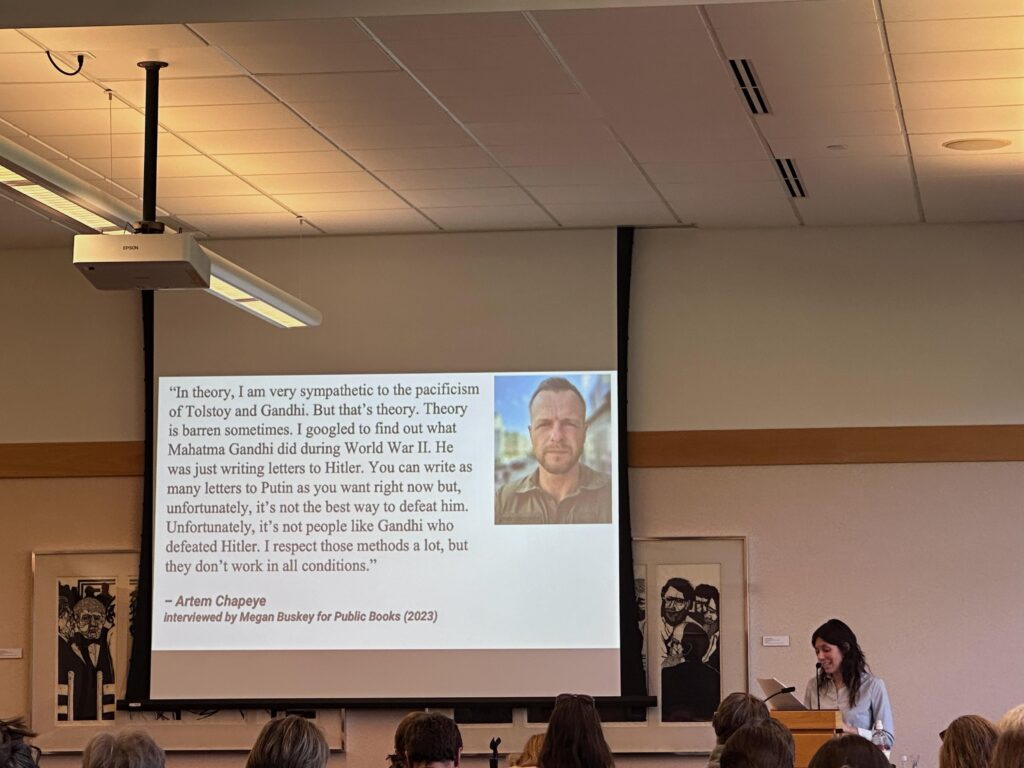

Sonya Bilocerkowyez gave the best lecture I attended outside of the keynotes. Sadly, it was also one of the least attended lectures. An American-Ukrainian, she’s the granddaughter of Ukrainians who were displaced during the Second World War. She happened to be teaching in Ukraine in 2014, when the Maidan Revolution kicked out the Russian puppet government and Russia invaded the Dobast and Crimea. Afterwards, she published a collection of essays titled, On Our Way Home from the Revolution: Reflections on Ukraine.

Her lecture was titled, “Whose Manuscripts to Burn? On the Role of the Writer during Wartime. Drawing on “cancel cultural” and “imperialistic language,” she spoke passionately about how Russia once again attempts to cancel Ukrainian identity. She credited her grandmother for teaching her an 1840 poem against Czarist imperialism.

She made four points on the role of the writer in war:

- The role begins before the war.

- The role is to document.

- The role is to save lives.

- The role is to free the land (Decolonization cannot be a metaphor).

Throughout her lecture, she drew on Ukrainian writers (such as Oksana Zabuzhko and Victoria Amelina, as well as those from Bosnia and Gaza.

Stacie Longwell Sadowski lead a lunch circle dealing with the use of social media for writers. As she and her husband maintain a site that encourages people to explore the outdoors, I joined her group and learned a bit more about what I am doing wrong . Actually, I did learn a lot from the luncheon circle. However, since I am not into monetizing my site, I’m not changing much. Check out her website, \Two Weeks in a hammock.

Anthony Doerr (closing keynote) Doerr was the reason I decided to make the trek to Grand Rapids for the conference this year. I am still amazed five years after reading his breakout novel, All the Light We Cannot See. He began the final keynote of the conference, before a packed house, speaking about similes. Doerr questioned if the age of similes is over. quoting polls and exposing outrageous similes he’d come across in his reading. He drew upon Homer and Superheroes and made fun of the mistakes he’d made in his slides.

Doerr was by far the funniest speaker I had heard at the festival. He was very free in his presentation which was given in Calvin’s fieldhouse. At one point, he pauses and looks up at the banners hanging around and says, “Calvin’s girls volleyball team must have really been good.” At another point, in this long diatribe on similes and metaphors, he pauses and looks around at the crowd and says what many were thinking, “You thought you were going to hear the bald guy talk about All the Light We Cannot See, didn’t you?”

Then Doerr made a serious turn. His talk about similes was to point to the interconnectedness of our violent and conflicted world. He suggested reading as a way for us to get beyond our self-centeredness and to make connections with the larger world. Next, he called for leaders who could make such connections. Then he encouraged writers, who have the advantage of metaphors, to bring these connections out in our writing. He advised us to tell stories, which are needed to bring our world together. It was a simple message that extended to 45 minutes through his humorous antidotes. When he was over, he received a standing ovation.

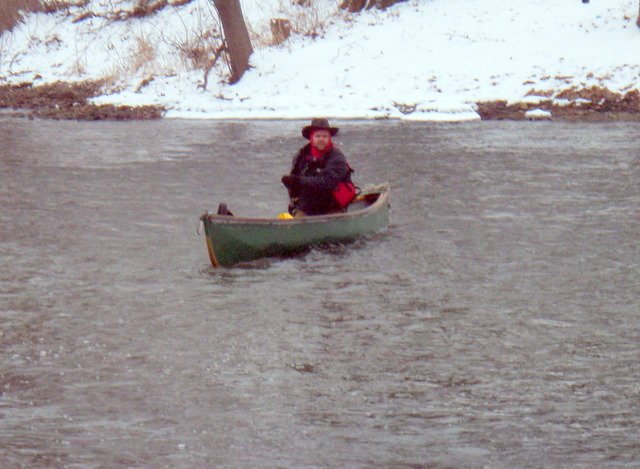

After the lecture was over, I met Bob, a friend of mine from Hastings, and the two of us drove up to Detour Village in the UP, arriving a little after midnight on April 14th. More about that later…

David Halberstam, Summer of ‘49, (1989, New York: HarperPerennial, 2002), 354 pages, with a bibliography, index, and some black and white photographs.

David Halberstam, Summer of ‘49, (1989, New York: HarperPerennial, 2002), 354 pages, with a bibliography, index, and some black and white photographs.