Ronald W. Hall, The Carroll County Courthouse Tragedy (2013 printing, Hillsville VA: Carroll County Historical Society,1998). 272 pages including sources and a few b&w photos.

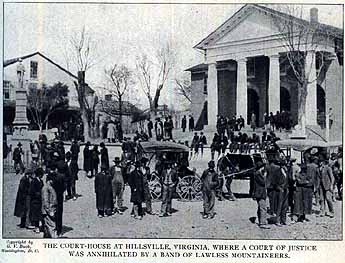

This is another book that I’ve read in order to learn about my new locale. In March 1912, there was a shooting at the Carroll County, Courthouse in Hillsville, Virginia. When all the smoke cleared, there were five dead, seven wounded. Two were executed and a number went to prison for their part in the tragedy. For a while, Hillsville was at the top of the nation’s newspaper. It would take another tragedy, the sinking of the Titanic, to remove the focus from Carroll County.

The shooting

The shooting began after the jury had found the defendant, Floyd Allen, guilty of forcefully releasing two prisoners (his sister’s sons) from law enforcement as they were bringing the prisoners back from Mt. Airy, North Carolina. The sentence would have had Floyd do time. Supposedly Floyd said, as the Sheriff and the Clerk of the Court approached to take him into custody, “I’m not going.” The shooting then started. There is still question as to what happened and who shot first. Was it Floyd’s son Claude? His brother, Sidna? Or the Clerk of Court Dexter Goad, who seems to have first pulled a gun? In the confusion there was a lot of shooting. Floyd, with a concealed pistol, began to shoot, but only after the mayhem began. When it was over the judge and the sheriff laid dead. Floyd had been seriously wounded. Those involved on the Allen side ran away. Some later turned themselves in. Others were captured. Two of whom, Sidna and his nephew Wesley, in Des Moines, Iowa where they were starting a new life.

What led up to the shooting

There are many questions as to what led up to this event, but it seems to have begun with Wesley Edwards getting a “red ear of corn” at a corn shucking. To find the “prized ear” meant he could kiss any girl there. The girl he chose to kiss led to a later fight at a church and resulted in a warrant for his arrest. The author also hints there were issues between the Democratic Allens and the Republicans who made up much of the “courthouse crowd.” If that’s the case, those against the Allens saw a way to get back at them. Family loyalty also played a role as the Allen/Edwards family stuck together to protect the Edward boys and later Floyd.

After the Edwards were charged with assault, they fled across the North Carolina border to Mt. Airy. The sheriff in Hillsville had the boys arrested there and handed over to his deputies at the state line. However, no extradition order was issued. As the deputies were taking the Edwards back to Hillsville, Floyd “released” the boys from custody. There are even questions as to what happened here. Did Floyd force their release or were they released into his custody? After all, he agreed he’d have the boys in court? Floyd even paid their bail.

The aftermath

The police of 1912 were not exactly professional. Officers often had a violent past. And forensic science was almost non-existent, at least in rural areas. No one secured the courthouse as a crime scene. Soon afterwards, folks dug bullets buried in the walls as souvenirs. Such tampering hindered the ability to link bullets to the guns fire or the direction from which they came.

With the death of the Sheriff and so many of the Allens on the loose, the state sent help. It also hired Baldwin-Felt hired detectives (a group like the Pinkertons). These mostly came from recent labor disputes in coal country and their mannerism didn’t endure them to anyone, it seems. Some of the detectives bragged about how many miners they’d killed. As if entitled, they took what they wanted or needed. In one case, after having ridden their horses to death, two of them took a man’s mules from his plow in the middle of the field.

After the shooting, because of the number of Allens in Carroll County, they housed the prisoners in Roanoke. Their trials took place in Wytheville. Convicted on capital murder, both Claude and Floyd were sentenced to death. Other members of the family received long sentences. There was a massive effort for the governor to commute the sentences of Claude and Floyd, including a petition with over 100,000 signatures. But the governor refused. The execution of father and soon occurred in 1913. The remaining prisoners received pardons (from a different governor) in the 1920s.

My recommendations

This is an interesting story of a time long past. There are still questions to be answered, but they probably never will be answered. The author is honest and at many times in the book admits we won’t know for sure what happened. Hall has done an outstanding job researching this subjectt.

I enjoyed the book even though it took me a while to get into it. The book begins with character sketches of the various parties involved. Not knowing all the details, I wasn’t sure what to do with this information. However, once the story began, it flowed better. This story could have been written in a Creative Non-Fiction genre. Doing so, the “opening details” could easily be incorporated into the larger narrative. Also, there were places where the author seemed to go out onto a tangent, such as explaining how electrocution became a means of capital punishment used on Floyd and Claude. This sideline didn’t add to the story. That said, I am glad to have read the book and I’ve learned more about this area.