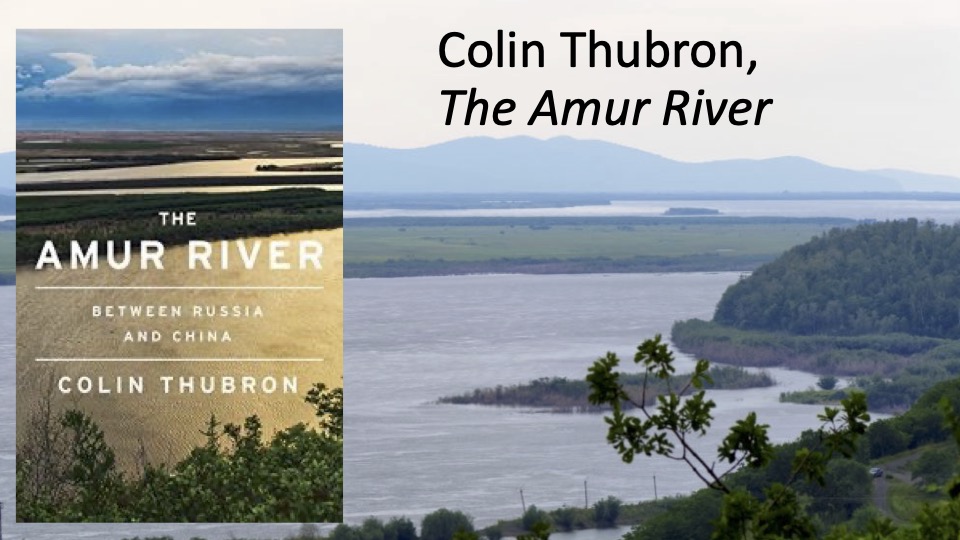

Colin Thubron, The Amur River: Between Russia and China (New York: HarpersCollins, 2021), 291 pages with an index and a map.

This is the second book I’ve recently consumed on the Amur River. I’m not sure of my renewed interest in Eastern Russia, but having once visited Siberia on the Trans-Mongolian Train from Beijing to Moscow, I had wanted to go back and take the train on to Vladivostok, and perhaps take a round trip, utilizing the BAM (Baikal-Amur Railroad). With the conditions of the world and Russia’s horrific war, such a trip may not be available during my lifetime. But maybe, if I can be as active as Thubron, who was nearly 80 when he made this trip, the world will settle down and I can make such a trip.

In July, I listened to the unabridged audible version of “Black Dragon River” which is the Chinese name for the river that runs between it and Russia. This is the 9th longest river in the world and the one few people have heard about, probably because much of it is off limits because of the fortified border. This is my third book by Colin Thubron. While traveling across Siberia in 2011, I read his book, In Siberia. I’ve also read Shadow of the Silk Road, which he describes a western trip along the old Silk Road, from China to the Mediterranean. Sadly, I didn’t review that book.

Thubron is a wonderful travel writer. In this book he describes his experiences as he attempted to follow the Amur and its tributaries from its source in Mongolia to the Pacific Ocean. Like Dominic Ziengler, in Black Dragon River, much of Thubron’s travels are mostly on land. But he says close to the river. He begins with an expedition in Mongolia, to find the headwaters of the Onon River, which requires special permission as they are entering a “strictly protected area”. While on this trip, he falls off his horse and breaks an ankle (but only thought it sprained) and cracks some ribs. But he continues to hobble along own despite his injury.

As he and his guides make their way through the northeast of Mongolia in a we learn about the Buryats of Russia, many who moved to Mongolia to escape Stalin, only to find themselves dealing with Khorloogiin Choibalsan, the leader of Mongolia after it became communist. Choibalsan was as cruel as Stalin, he just had fewer subjects to torment. It is estimated that between 1937 and 1938, when the purges in Mongolia were the worst, ½ of the nation’s intelligentsia and 17,000 monks were killed.

Tubron leaves Mongolia and picks up a Russian guide, following the Onon River. After the confluence with the Ingoda River, the Onon becomes the Shilka River. He stops in towns along the way which appear to have seen their better days. He’s asked about his purpose. When he says he’s following the Amur to the sea, he’s informed he’s on the wrong river, that the Amur is far away. It’s as if people don’t realize that the Shikla is the main tributary to the Amur. He also has run in with Russian security, who are suspicious of his travels. But after a few days, it works itself out. Part of the problem may have been he accidentally saw the maneuvers along the Amur with Russian and Chinese troops.

After the confluence of Argun and Shilka Rivers, which form the Amur, the river becomes the boundary between Russia and China. While it is a fortified, there is some trade across the river. But there is also much prejudice, with the Russians looking down on the more prosperous Chinese, who many see is only interested in making money. At the city of Blagoveshchensk, Thubron crosses the river into the much larger Chinese city of Heihe. From here, he begins to travel along the river’s southside, before crossing back into Russia where the Ussuri River meets the Amur. In the border city of Khabarovsk, he learns of archeologists who have discovered ancient Chinese artifacts being punished as the Russians doesn’t want the Chinese to have any claim to their territory. Russia claim on its eastern land is weak. It was only after the building of the trans-Siberian railway that the country was united, and much of its land in the east was squeezed by treaties from a weaken China.

While the border seems to be somewhat stabilized along the Amur, many Russians have xenophobic views about the Chinese. Eastern Siberia is a long way from Moscow. In some ways, both sides of the border are frontiers. But most of the Russians Thobron meets on his travels are Europeans and they feel China is destroying their forest and lands for their own development. By the time Thorbon reaches Khabarovsk, it’s October. He’s been traveling since August. The river is beginning to freeze, so he heads back to the United Kingdom for the winter.

The next June, Thubon returns to Siberia. After Khabarovsk, the river turns north. From here, the Ussuri River, which flows from the south, becomes the border with China. Thubon travels along both sides, stopping in remote places, traveling with a Russian outdoorsman who takes him fishing and discusses survival in the deep cold of winter. He gains a vision of another side of Siberia. Most of this area is remote, except for Komsomolsk-na-Amure, which is where the BAM (Baikal-Amur Railway) crosses the river. This was a site of Soviet weapon factories which has produced aircraft. Along the river, nuclear submarines were built. But Thubon is not able to secure a permit to visit these sites and continues to make his way by car and boat to the river’s mouth into the Pacific. made this trip, most of the capacity is limited.

I enjoyed reading this book. It reads like a travelogue, with the author providing just enough detail to give you a feel for the land and its history. While I also enjoyed Black Dragon River, it felt less like a travelogue as Ziengler goes much deeper into the history, not only of the Amur, but of the Mongolian and Chinese influence in the larger world. Both books are worth reading. My one complaint is that Thorbon tends to use obscure words, especially adjectives. But he writes some beautiful sentences. An example: “Perhaps it is the intimacy of the town, cradled in its hills and wrapped by the river, that sheds a gentle euphoria.”

Thubron had a number of colorful descriptions of these such as “mushroom caps”