Two weeks ago, in a sermon, I told about the “duck parties” held at seminary. Today, I am posting a story about some nonsense that occurred during my first term at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Other recent posts include memories of Professor von Waldow and Dean Mauser and his secretary. Good memories.

My only experience in dorm-living was my first year in seminary. I boarded on the third floor of Fisher Hall. I stayed in the dorm to save expenses as I still had a house and mortgage payments when I left for seminary (I sold the house soon afterwards).

Across from my room was Ken, a student from Japan. A language whiz, Ken spoke several Slavic languages but needed work on his English. We did our best to help, but who among us will forget the day he asked a visiting professor from Prague a question. Unable to get his question across in English, he switched to Russia or Czech or something strange and the professor answered him in an equally strange tongue. The rest of us sat around witnessing a firsthand example of glossolalia.

Down the hall, to the north, was Keith. A United Methodist student, Keith also managed the school’s hockey rink. When not in use, the hockey rink served as the hallway for third floor Fisher. Being from the South, hockey was something new to me and I did my best to avoid the games.

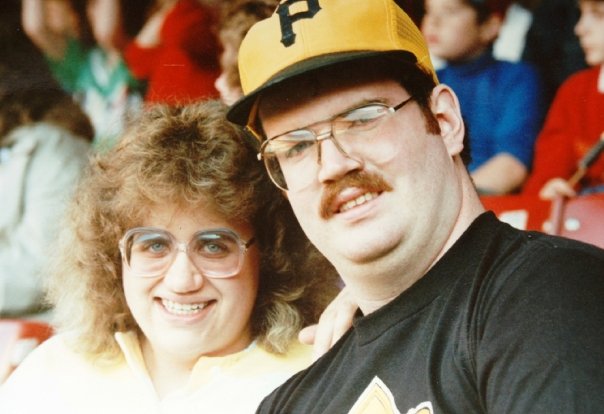

In the room next to mine, to the south, was Jim. Unfortunately, he dropped out before the two of us could finish what would have been a best seller: “A Theological Drinking Guide to Pittsburgh.” Having been used to living in a house, and with nightly hockey matches going on outside my door, getting out to the local bars around Pittsburgh (many within walking distance) was an escape and a way to maintain sanity.

There were many others on the floor, but the four of us played a prominent role in the “perfect storm” that just about got me booted back to the piney woods of North Carolina.

The room to my north, between mine and Keith’s, was empty. Keith read an article on Christian sexuality written by Rodney Clapp. Being a careful reader, what caught Keith’s attention was the author’s name. It seemed fitting a man whose last name was slang for a venereal disease would write on sexuality. Keith decided Clapp needed to be a classmate. He made up a nameplate for the empty room. “That’s Clapp’s room,” we’d tell people, he’s an esteemed alumnus from Pittsburgh and maintains a room here. A week or so later, Clapp’s pretend presence on campus took a strange twist.

Ken, who’d just arrived in American, became fascinated with a certain group of American newspapers generally found in the check-out lines at the supermarket. He read these papers religiously, trying to improve his English and learn about this strange country in which he was living. One day, at the local Giant Eagle Supermarket, he picked up a copy of the National Enquirer, or maybe one of the other tabloids. The lead article featured the story of an unnamed hell-fire preacher who spontaneously combusted in the pulpit. After his particularly fiery sermon, all that was left was ashes. It must be true. It was in print. Such an event should have certainly been studied in homiletics, but I don’t recall it being mentioned.

As no one had seen Clapp recently, it was logically assumed he was the unnamed preacher. Ken posted the article on Clapp’s door. Over the next week, letters from all around the world started appearing, in different languages, offering condolences to Rodney’s family and friends. Clapp’s deeds and misdeeds were recalled.

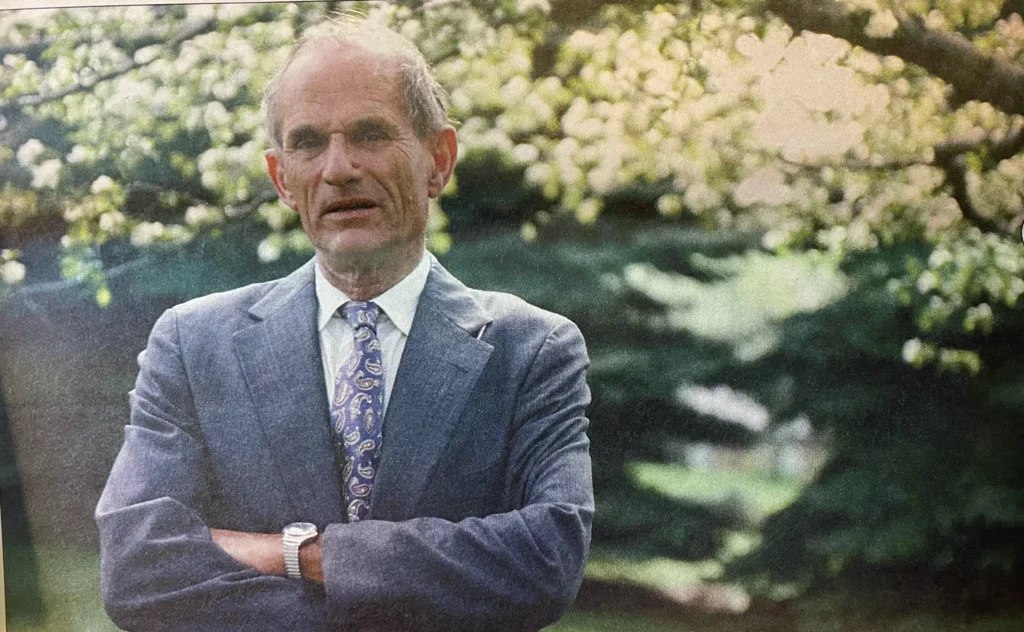

Around this time, for reasons I still don’t understand, had chapel duty. Normally first-year students were exempt, but for some reason I said I’d do it. I thought daily chapel would be the perfect setting for a “Rodney Clapp Memorial Service.” Somehow, word got out to the powers-that-be what was being planning. Dr. Oman, the homiletics professor, called me into his office and informed me there would be no faux funeral in chapel.

Disappointed at being unable to involve the entire community, we planned our own funeral. Although not a Protestant tradition, we included a wake. We could be ecumenical if it meant a good party. On December 2, 1986, after an evening of basketball (after all, we did have our priorities), a crowd of us gathered in the Fisher lounge for Clapp’s wake and funeral. In the center of the room, laid out like a casket, was the door from Clapp’s room. It was covered with letters of condolences and tokens of our love and adoration for him. Sitting on the top of the door was a plastic container holding some ashes someone obtained.

We gathered around Clapp’s remains and said our goodbyes. We read scripture. Chosen passages alluded to fire. Nonsensical tales about our experiences with Clapp were shared. Taking great liberty with the funeral liturgy, we replaced hymns with more appropriate music such as the Doors’ “Light My Fire” and Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water.” Afterwards, as Clapp’s ashes floated out the window and across the lawn, we had a final toast.

With the funeral out of my way, I still had to do my duty in chapel. A day or two later I stood before the crowd of students and professors and delivered one of those boring first year seminary student sermons. The best part of it were a few lines of poetry I quoted from John Beecher, whom I felt deserved an introduction.

The service was dreadfully serious until I was about halfway through my message. Before the service, Jim came into the chapel and took two fire extinguishers off the walls by the doors. Unbeknownst to everyone, he placed the extinguishers on the chancel, one on each side of the pulpit. As I was trying to make a serious point which I’m sure expressed some eternal consequence, someone in the row of students from Fisher Hall noticed the fire extinguishers. He began to laugh while pointing it out to the person next to him. Slowly, like a wave moving across the chapel, each student poked the guy next to him and pointed to the fire extinguishers. The laughter spread. Soon, among a crowd of somber Presbyterians, one pew laughed hysterically. I smirked, bit my tongue, and looked down at my notes. I knew if I looked out upon the gathered congregation, all would be lost.

I’m sure most of those in chapel that day, unaware of the joke that had been building for a month, felt those of us from Fisher Hall were downright rude. And they were right.