I am heading to a conference at Ghost Ranch, a Presbyterian Conference Center in North New Mexico, so there will be no sermon this week. Instead, let me catch up by providing three short (for me) book reviews of works I recently read (or listened to the unabridged audio book).

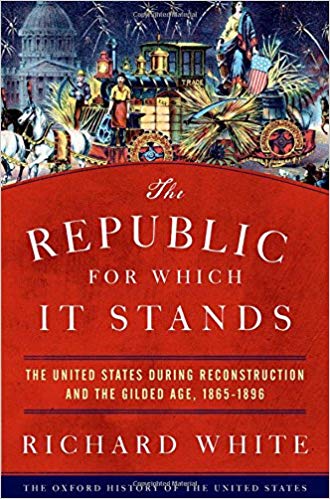

Richard White, The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896 (Oxford, 2017), 928 pages

This book is a part of the Oxford History of the United States collection. Richard White is a noted Western United States historian and author of It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own: A New History of the American West (Oklahoma, 1991). It’s a massive book that begins with the death of Abraham Lincoln and ends with the election of William McKinley.

White merges together two eras that are often separated by historians: reconstruction and the Gilded Age. He makes the case that the two should be connected. This was the age that America was rising to its world prominence. It was also an age where the country was growing rapidly, especially through immigration. As a uniting theme for this period, White choses the home. The home found itself under attack as the country shifted from the home being the basis of the economy dependent on small farms to a nation of industry where workers toiled for wages. Although politicians on both sides of the aisle would lift up the home as the ideal, the home (as the White Protestant ideal) was under attack and rapidly changing during this period. Economically, this was the period of the gold standard. White’s knowledge of the West, where mining had a vested interest in bimetallism (using both gold and silver for currency), helps him to navigate this debate. Another economic concept that was highly debated was the meaning of labor. As the economy changed from farming to industry, who free were corporations and workers to collectively bargain. This leads for long discussions about court decisions, especially around the 14th Amendment.

In the book’s forward, it was noted that a grammatical change occurred within America following the Civil War. Before the war, people would say, “The United States are…” After the war, people would say, “The United States is…” During this era, in which America filled in the vast territories of the West with states, the United States became the country we know. Only a handful of states were added after 1896.

I enjoyed this book, but then this is the period I have studied the most. My first college class, taken in the summer between high school and college, was a history class that focused on United States and Europe from the 1870s through the First World War. And I would later write a dissertation in this era, focusing on the church’s role in the Nevada mining camps. White covers a lot of material in this book (and his lists of sources at the end of the book could keep a historian busy for a lifetime). This is a wonderful addition to the Oxford History of the United States collection.

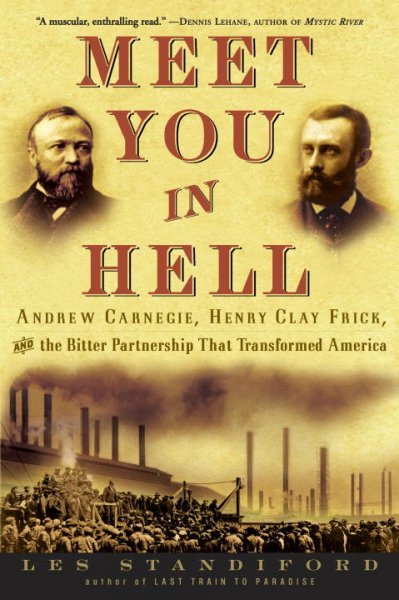

Les Standiford, Meet You in Hell: Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and the Bitter Partnership That Changed America (Broadway Books, 2006), 336 pages

I listened to an unabridged copy of this book.

This was my third book by Standiford and I have enjoyed them all. I have twice read Last Train to Paradise, which is about Henry Flagler and the building of the East Coast Florida Railway to Key West. I have also read The Man Who Invented Christmas which is about Charles Dickens and the publication of A Christmas Carol. As with his writings of Flagler, in Meet You in Hell, Standiford turns again to industrial titans of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, looking at the partnership between Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick. When Carnegie merged his steel empire with Frick’s coal and coke (a purified form of coal used in steel making), a mighty industry began that eventually led to the corporation known as United States Steel. But it wasn’t a smooth partnership. The two were willing to stab the other in the back, which led to bitter conflicts in both business and in politics (their last great rivalry was Frick opposition to what became the League of Nations, while Carnegie supported the effort to bring nations together in order to end war. Although a “peacemaker”, Carnegie made a lot of money supplying steel plates for the American navy.

The title comes from a request from Carnegie to meet with Frick shortly before his death. Frick’s responded back, “I’ll meet you in hell,” noting that he felt that was both of their destinations in the life to come.

The highlight of this story is the 1892 Homestead Strike. The strike occurred while Carnegie was summering in his native Scotland. Frick played hardball with the miners, bringing in Pinkerton’s which led to a bloody stand-off. Frick himself was even shot, but not by a striker. An anarchist attacked Frick following the strike. To the workers Frick became a hated man. Many thought it would have been different had Carnegie had been at the helm. In fairness to Frick, Standiford points out how Carnegie also undermined unions even while speaking positively about them.

In addition to providing insight into their business partnership, this book provides short biographies of both men and covers their life after they had made their fortunes. Carnegie went on to build libraries and establish foundations. Frick established a top-notch art gallery in New York and also a large park in Pittsburgh.

In the last chapter, Standiford attempts to link the early 21st century with the ending of the 19th century. While there are similarities (little wage growth for workers, few union members, expansive growth and income for corporations and management), I think he’s stretching it as we are in completely different economies. Still, as one who has read several books about Homestead, I enjoyed and learned much from this book.

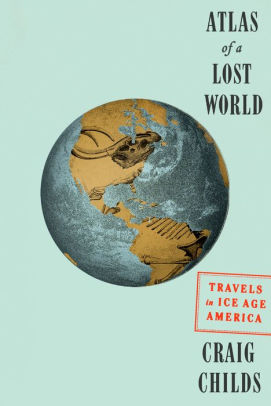

Craig Childs, Atlas of a Lost World: Travels in Ice Age America (Pantheon Books, 2018), 270 pages.

Like the above two books, this is also a history book, but it goes back a lot further and covers a time frame that extends from roughly 30,000 years ago to 12,000 years ago, at a time where North America big game hunters were going after mammoths animals that make the modern day bison appear puny, The book is also a travelogue in which the author spends time on the Bering land bridge and popular hunting areas from the Pacific Northwest to Mexico and east to the Florida panhandle. At each site, Child’s informs the reader about the tools used to hunt the animals and theories as to how they lived, while imaging what it the area would have been liked during the ice age. Childs and his companions suffered to cross Alaskan mountain ranges and to deal with a buggy and wet campsite in Florida. On another occasion, they play-act the last great hunt of the beasts who were gone from the Americas over 13,000 years before Europeans arrived. At another site in Northern Minnesota, Childs freezes his butt off camping in the winter.

Atlas of a Lost World was interesting. I learned a lot about tool making and Childs personal relationships (he and his wife split up somewhere between Alaska and Florida, I’m not sure where), but I felt the book lacked a purpose that could have strengthened it. Childs does attempt to link the dying off of the great mammals with climate change, but that seems a little stretched. Certainly, the reader comes away from the book understanding that change is constant on earth, as species die and others adapt.

Childs is an accomplished outdoorsman, but I question his knowledge of poisonous snakes in the Southeast. He seemed to be overly concerned with the deadly poisonous cottonmouths (water moccasins) dropping from trees into boats. These snakes aren’t known for climbing trees. There are several types of water snakes, some with similar markings to the cottonmouth, who do climb trees, but they are not poisonous. Of course, it’s more exciting to worry about a poisonous snake dropping in one’s boat. A cottonmouth might still fall into a boat, but not from a tree. They are known to sun on logs and if you bumped the wrong log with your canoe, the snake might slide off in an attempt to get away from you and end up where you don’t want him.

This is my third book by Childs, who is by training a water hydrologist. The first book I read of his is my favorite, The Secret Knowledge of Water. I later read The Soul of Nowhere In this work, he studies another long-gone group of people, the Anasazi, whose civilization flourished until around the year 1200, when they seemed to die out, although they are probably the ancestors of the Hopi, Navajo, and other Native American tribes in the American West.

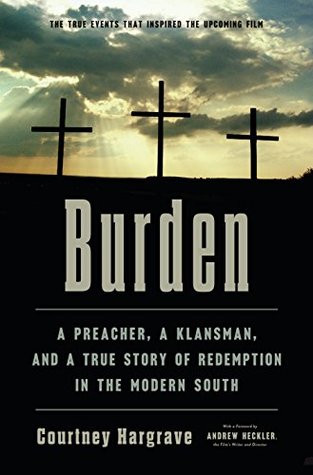

Arthur Brooks, one of this year’s Calvin January Series speakers, had a new book come out this month. I read the first half of it this past week. It’s titled, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America from the Culture of Contempt. I highly recommend it. Brooks’ points out that anger isn’t our problem. What he sees as a problem is contempt. When we are angry, we are generally wanting something better. When we hold someone in contempt, we are essentially wishing they didn’t exist. In a chapter titled “The Culture of Contempt,” he suggests that much of America, even though we hate it, are addicted—there’s that word again—to political contempt. We don’t like what this contempt does to us (not to mention those we disagree with), but we can’t seem to get enough of it. Like a junkie, we “indulge” in the habit. And the media, who has economic interest in our addiction, is more than happy to feed us.

Arthur Brooks, one of this year’s Calvin January Series speakers, had a new book come out this month. I read the first half of it this past week. It’s titled, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America from the Culture of Contempt. I highly recommend it. Brooks’ points out that anger isn’t our problem. What he sees as a problem is contempt. When we are angry, we are generally wanting something better. When we hold someone in contempt, we are essentially wishing they didn’t exist. In a chapter titled “The Culture of Contempt,” he suggests that much of America, even though we hate it, are addicted—there’s that word again—to political contempt. We don’t like what this contempt does to us (not to mention those we disagree with), but we can’t seem to get enough of it. Like a junkie, we “indulge” in the habit. And the media, who has economic interest in our addiction, is more than happy to feed us. Do any of you remember the old movie, City Slickers? It doesn’t seem to be old, but the movie was released in 1991. It starred Billy Crystal who, with a group of his friends from the city, decide to go out west for a few weeks to help round up cattle. In one scene, Crystal is riding on a horse beside Curly, an old fashion cowboy who could have been the Marlboro Man. When Crystals asks about his secret to being content in life, Curly points his index finger and says it’s this. Crystal is confused and asks, “You’re finger?” Curly shakes his head and replies it’s just one thing. Of course, Curly isn’t able to tell Crystal what’s his one thing is, that’s for him to find out. This “one thing” is now known as Curly’s law.

Do any of you remember the old movie, City Slickers? It doesn’t seem to be old, but the movie was released in 1991. It starred Billy Crystal who, with a group of his friends from the city, decide to go out west for a few weeks to help round up cattle. In one scene, Crystal is riding on a horse beside Curly, an old fashion cowboy who could have been the Marlboro Man. When Crystals asks about his secret to being content in life, Curly points his index finger and says it’s this. Crystal is confused and asks, “You’re finger?” Curly shakes his head and replies it’s just one thing. Of course, Curly isn’t able to tell Crystal what’s his one thing is, that’s for him to find out. This “one thing” is now known as Curly’s law. I suggest that the one thing Jesus points out to Martha was himself. Serving others is good, doing a good deed such as feeding visitors is commendable, but there is a deeper human need and if we don’t ground ourselves there, we burn out. As humans, we have a need to connect with others and as a Christian, our need includes a connection to Jesus. How do we go about this? Let’s see what our text says.

I suggest that the one thing Jesus points out to Martha was himself. Serving others is good, doing a good deed such as feeding visitors is commendable, but there is a deeper human need and if we don’t ground ourselves there, we burn out. As humans, we have a need to connect with others and as a Christian, our need includes a connection to Jesus. How do we go about this? Let’s see what our text says. Jesus isn’t telling Martha to be inhospitable. Hospitality is an important trait of Christians. We are told in the book of Hebrews: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for in doing so some have entertained angels without even knowing it.”

Jesus isn’t telling Martha to be inhospitable. Hospitality is an important trait of Christians. We are told in the book of Hebrews: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for in doing so some have entertained angels without even knowing it.” Finally, Martha has enough. Here, she is fixing a nice sit-down dinner, and while she’s working, her sister enjoys Jesus’ company. Perhaps, Martha’s a little envious… She tries to get Jesus on her side by appealing to his compassion. “Lord, doesn’t it bother you that I’ve had to do all the work?” she asks. Reading between the lines, we get the idea she really wants to say, “Tell Ms. Couch Potato to get in here and help…” Do you sense the contempt is rising in Martha?

Finally, Martha has enough. Here, she is fixing a nice sit-down dinner, and while she’s working, her sister enjoys Jesus’ company. Perhaps, Martha’s a little envious… She tries to get Jesus on her side by appealing to his compassion. “Lord, doesn’t it bother you that I’ve had to do all the work?” she asks. Reading between the lines, we get the idea she really wants to say, “Tell Ms. Couch Potato to get in here and help…” Do you sense the contempt is rising in Martha? Are we like Martha? Do we worry and become distracted over so many things that we are unable to see what’s truly important? Do we keep our lives so busy that we have no real quality time to spend with friends? (I’m guilty). If so, we just might be missing something important… After all, Martha missed a chance to spend time listening to our Lord’s teachings. Don’t forget about hospitality, but remember that it’s not the only thing.

Are we like Martha? Do we worry and become distracted over so many things that we are unable to see what’s truly important? Do we keep our lives so busy that we have no real quality time to spend with friends? (I’m guilty). If so, we just might be missing something important… After all, Martha missed a chance to spend time listening to our Lord’s teachings. Don’t forget about hospitality, but remember that it’s not the only thing. You know, this is a busy time here at Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church. The Session has begun working on a strategic plan for the future. A small group of Elders have spent a lot of time on this project. This week, the rest of the Elders will join in the process, and then we’ll be asking for your help and ideas. This is good and needed work, but I encourage us to not be distracted from that which we truly need… Jesus Christ. Without Jesus, what we do will mean nothing. He’s our reason for being, for he calls us together in communion with him. So remember the main thing. Make sure to take time to spend with Jesus, daily. If you do, the rest will fall into place. Amen.

You know, this is a busy time here at Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church. The Session has begun working on a strategic plan for the future. A small group of Elders have spent a lot of time on this project. This week, the rest of the Elders will join in the process, and then we’ll be asking for your help and ideas. This is good and needed work, but I encourage us to not be distracted from that which we truly need… Jesus Christ. Without Jesus, what we do will mean nothing. He’s our reason for being, for he calls us together in communion with him. So remember the main thing. Make sure to take time to spend with Jesus, daily. If you do, the rest will fall into place. Amen. Belden C. Lane, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Exploring Desert and Mountain Spirituality (Oxford University Press, 1988), 282 pages including notes, index, and some photos included within the text.

Belden C. Lane, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Exploring Desert and Mountain Spirituality (Oxford University Press, 1988), 282 pages including notes, index, and some photos included within the text.

We’re looking at the 23rd Psalm today. It’s a prayer of faith not often heard on Sunday mornings; we save it for funerals. Wayne Muller in book, Sabbath, Restoring the Sacred Rhythm of Rest, points this out:

We’re looking at the 23rd Psalm today. It’s a prayer of faith not often heard on Sunday mornings; we save it for funerals. Wayne Muller in book, Sabbath, Restoring the Sacred Rhythm of Rest, points this out:

The Northeast Cape Fear River broadens and deepens as it flows through Holly Shelter Swamp. In this area, on a high bluff on the east bank of the river was my scout troop’s favorite camping site. The ridge was forested with tall long-leaf pines. Lining the banks along the river were dogwoods, tupelo and cypress, their branches adorned with Spanish moss. The leisurely pace of the river invited us boys to sit on its banks and throw sticks into the water, watching them slowly float away. It’s the type of life Mark Twain wrote about on the Mississippi, a life of ease beside peaceful waters that seem to hold some mysterious power to heal, to forget our troubles, and to be renewed.

The Northeast Cape Fear River broadens and deepens as it flows through Holly Shelter Swamp. In this area, on a high bluff on the east bank of the river was my scout troop’s favorite camping site. The ridge was forested with tall long-leaf pines. Lining the banks along the river were dogwoods, tupelo and cypress, their branches adorned with Spanish moss. The leisurely pace of the river invited us boys to sit on its banks and throw sticks into the water, watching them slowly float away. It’s the type of life Mark Twain wrote about on the Mississippi, a life of ease beside peaceful waters that seem to hold some mysterious power to heal, to forget our troubles, and to be renewed. In the late afternoon, things would change. As the sun dropped in the west behind trees, it created long shadows on the black waters. An eeriness descended. Spanish moss now appeared as the long beards of men whose mysterious and untimely death occurred in the backwaters of Holly Shelter Swamp. We had been warned.

In the late afternoon, things would change. As the sun dropped in the west behind trees, it created long shadows on the black waters. An eeriness descended. Spanish moss now appeared as the long beards of men whose mysterious and untimely death occurred in the backwaters of Holly Shelter Swamp. We had been warned. Yea through I walk through the valley of the shadow of death.” This most beloved psalm, as I pointed out, is ubiquitously used at funerals and mostly overlooked on Sunday mornings. This is unfortunate for the psalm tells us about a life lived well—a life lived in complete trust of God the Father.

Yea through I walk through the valley of the shadow of death.” This most beloved psalm, as I pointed out, is ubiquitously used at funerals and mostly overlooked on Sunday mornings. This is unfortunate for the psalm tells us about a life lived well—a life lived in complete trust of God the Father. Psalm 23 is attributed to King David and it certainly brings to mind key elements of his early life. As a young shepherd, he knew what it meant to lead sheep through dangerous mountainous terrain. As a mere boy, he was willing to face the giant Goliath on the battlefield. As a young man, he was being chased by the armies of King Saul, who knew he was God’s anointed. And even as an old man with many enemies, he knew the pain of having his own son attempting to take his throne. Of course, we know David had many short-comings, but he made up for them by putting his faith in God’s hands. David was a man, the scriptures tell us, after the very heart of God.

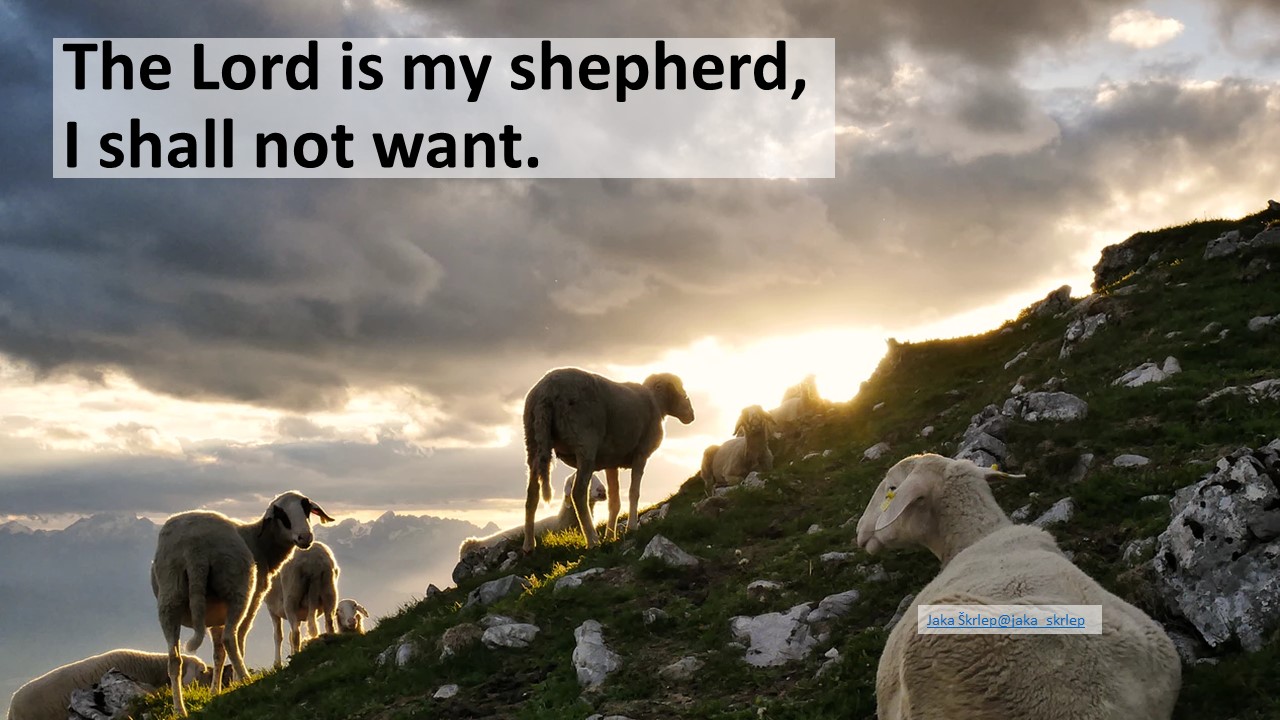

Psalm 23 is attributed to King David and it certainly brings to mind key elements of his early life. As a young shepherd, he knew what it meant to lead sheep through dangerous mountainous terrain. As a mere boy, he was willing to face the giant Goliath on the battlefield. As a young man, he was being chased by the armies of King Saul, who knew he was God’s anointed. And even as an old man with many enemies, he knew the pain of having his own son attempting to take his throne. Of course, we know David had many short-comings, but he made up for them by putting his faith in God’s hands. David was a man, the scriptures tell us, after the very heart of God. The opening verse captures the essence of the Psalm. “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.” The Psalm begins with a powerful metaphor of God as a shepherd. Of course, God is more than just a shepherd, which was a lowly occupation in ancient Israel. God is the Creator, the judge, the warrior, the righteous one, the ancient one. All these images remind us that God is greater than just a mere tender of sheep, but like a shepherd who is devoted to his sheep, God is devoted to his people, which makes the shepherd image the perfect depiction of our relationship with God the Creator.

The opening verse captures the essence of the Psalm. “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.” The Psalm begins with a powerful metaphor of God as a shepherd. Of course, God is more than just a shepherd, which was a lowly occupation in ancient Israel. God is the Creator, the judge, the warrior, the righteous one, the ancient one. All these images remind us that God is greater than just a mere tender of sheep, but like a shepherd who is devoted to his sheep, God is devoted to his people, which makes the shepherd image the perfect depiction of our relationship with God the Creator. There are two great images at the end of this Psalm. First, there is a table set in the presence of our enemies. Royal banquets are often used in scripture to point to an eschatological future, the promised heavenly banquet where Jesus is at the head of the table and serves us. Perhaps the presence of our enemies is an invitation for them, too, to come to the table. They, too, have been created by a God who delights in bringing about reconciliation and encourages us to seek out peace with our enemies.

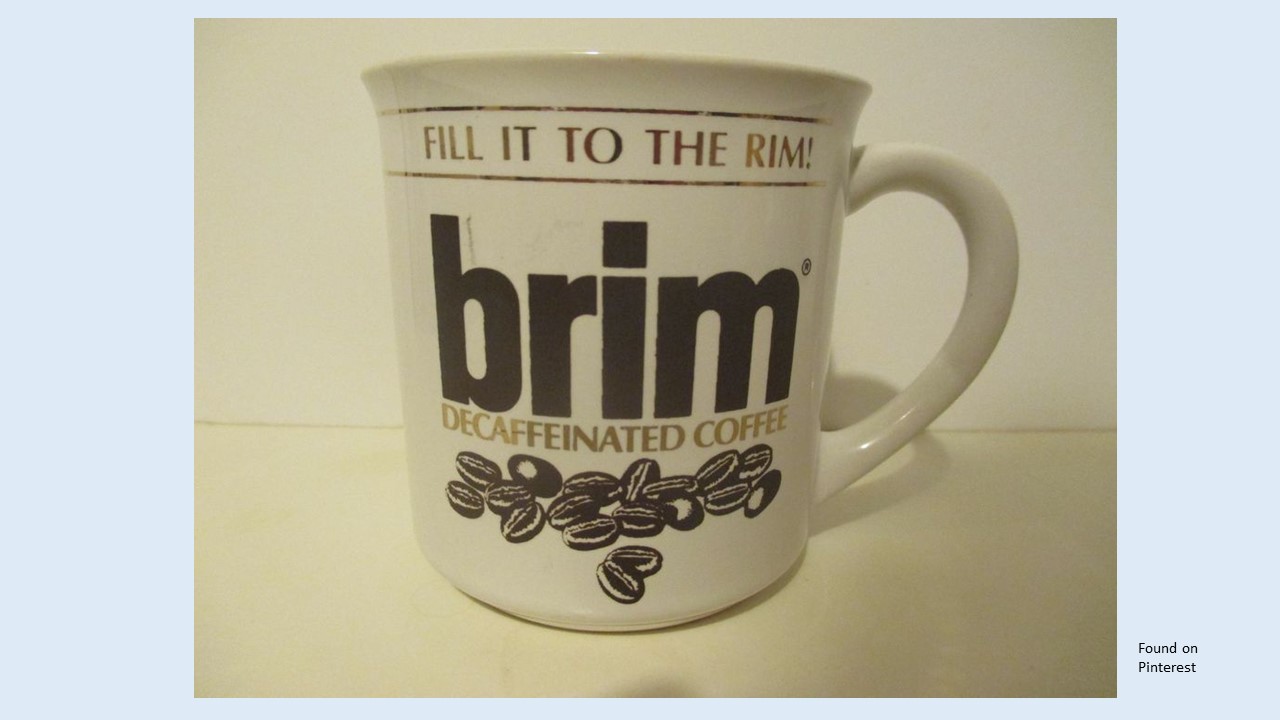

There are two great images at the end of this Psalm. First, there is a table set in the presence of our enemies. Royal banquets are often used in scripture to point to an eschatological future, the promised heavenly banquet where Jesus is at the head of the table and serves us. Perhaps the presence of our enemies is an invitation for them, too, to come to the table. They, too, have been created by a God who delights in bringing about reconciliation and encourages us to seek out peace with our enemies. The second image is the cup running over. Back in the 70s and 80s, Brim decaffeinated coffee had a series of advertisements about filling our coffee cups to the rim. We don’t serve Brim in the fellowship hall. The ad world is a perfect one and no one that I remember in those commercials spilled coffee on the rug, even when the cup couldn’t contain another drop. But here, in Psalm 23, we’re promised something even greater that being filled to the rim. Our cup overflows! This is a promise of abundance.

The second image is the cup running over. Back in the 70s and 80s, Brim decaffeinated coffee had a series of advertisements about filling our coffee cups to the rim. We don’t serve Brim in the fellowship hall. The ad world is a perfect one and no one that I remember in those commercials spilled coffee on the rug, even when the cup couldn’t contain another drop. But here, in Psalm 23, we’re promised something even greater that being filled to the rim. Our cup overflows! This is a promise of abundance. When things are looking down, when life is busy and we can’t seem to get a break, we can go to this Psalm and be reminded that we are not alone. God’s goodness abounds. God’s goodness will overflow in our hearts and lives, giving us a new perspective on the challenges we face. Amen.

When things are looking down, when life is busy and we can’t seem to get a break, we can go to this Psalm and be reminded that we are not alone. God’s goodness abounds. God’s goodness will overflow in our hearts and lives, giving us a new perspective on the challenges we face. Amen.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

You know, when it comes to religion, we often think it’s about being good, or good enough. We think we need to be like Jig in one of his purifying stages. We see religion as hard work which is why many people don’t want to be bothered with it. We forget about the joy of salvation.

You know, when it comes to religion, we often think it’s about being good, or good enough. We think we need to be like Jig in one of his purifying stages. We see religion as hard work which is why many people don’t want to be bothered with it. We forget about the joy of salvation.

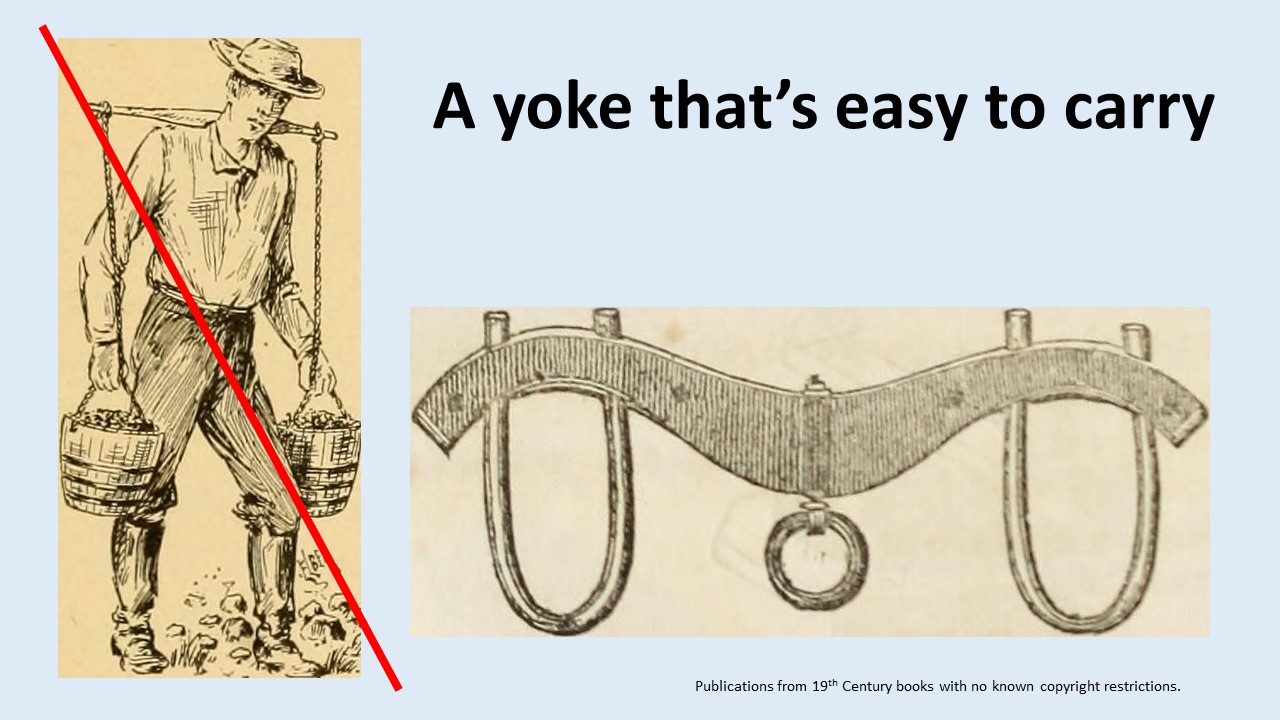

So Jesus invites us saying, “Come to me; take my yoke.” He’s not talking about a single yoke, one that he gives us and we wear around so that we might haul a heavy load. Instead, I think he offers a double yoke, one that he helps share the load. One in which we are able to watch him and learn how to live graciously, to appreciate beauty and to give thanks for the blessings of life. Our translation tells us Jesus’ yoke is easy, but it could also be translated as kind

So Jesus invites us saying, “Come to me; take my yoke.” He’s not talking about a single yoke, one that he gives us and we wear around so that we might haul a heavy load. Instead, I think he offers a double yoke, one that he helps share the load. One in which we are able to watch him and learn how to live graciously, to appreciate beauty and to give thanks for the blessings of life. Our translation tells us Jesus’ yoke is easy, but it could also be translated as kind

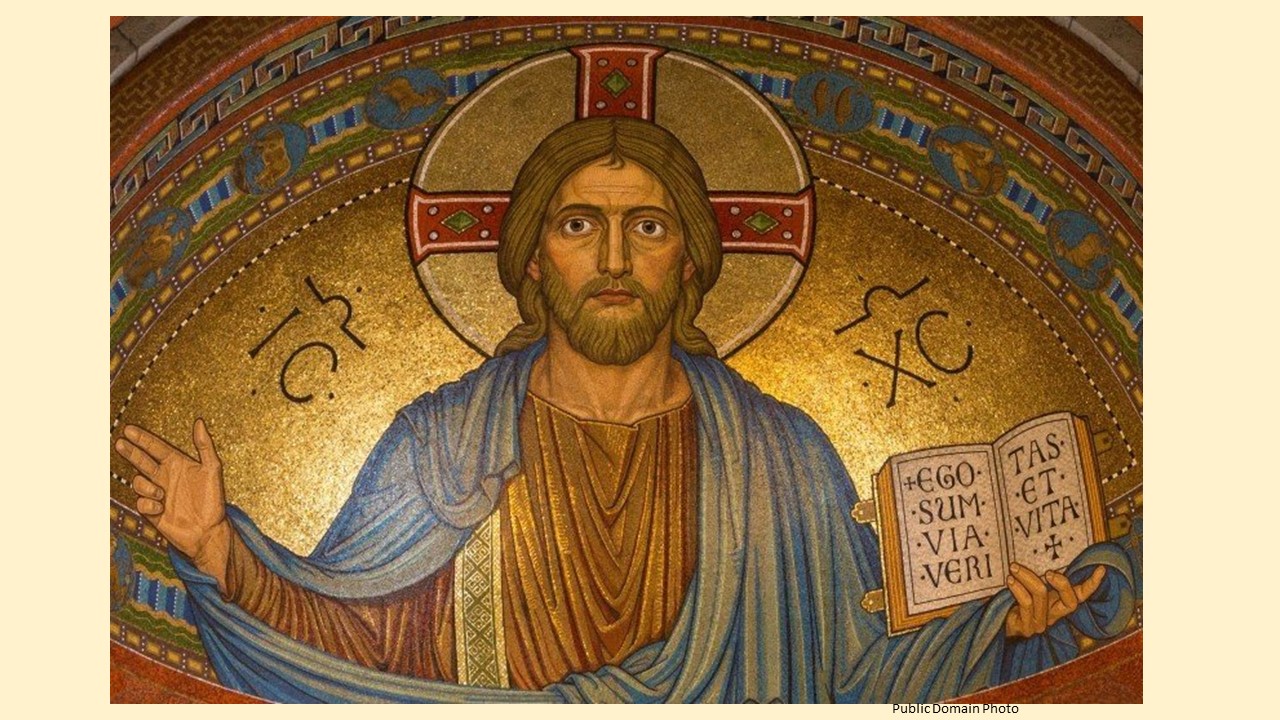

esus calls us to come and learn from him how to enjoy life. He calls us to relearn our priorities, to set the right tempo. Instead of having to work hard to earn God’s grace, we accept it and thereby joyously labor not for God’s grace but to praise God for having been so good to us. We don’t have to be so rushed, because we know God is in control. We don’t have to do it all, for we trust in God’s providence. We don’t have to pretend to be God. Let that burden go!

esus calls us to come and learn from him how to enjoy life. He calls us to relearn our priorities, to set the right tempo. Instead of having to work hard to earn God’s grace, we accept it and thereby joyously labor not for God’s grace but to praise God for having been so good to us. We don’t have to be so rushed, because we know God is in control. We don’t have to do it all, for we trust in God’s providence. We don’t have to pretend to be God. Let that burden go! Take care of yourself. Reorient your life to a new perspective, one with Jesus, as the face of God

Take care of yourself. Reorient your life to a new perspective, one with Jesus, as the face of God

We are coming to the end of our series on the “Land Between,” and our study from the 11th Chapter of the Book of Numbers. Next week, we’ll begin our Lent Journey, as we make our way toward Easter. Our theme for our Lenten series will be “Busy.” It’s a timely series; we all struggle with busyness. As a way of catching our breath, we’re going to be encouraged by scripture to reconnect to an unhurried God. As a warning, we’ll be doing a few different things in worship. It’ll be exciting, so come and invite others who feel hurried in life to join us for a refreshing break each week as we gather on Sunday.

We are coming to the end of our series on the “Land Between,” and our study from the 11th Chapter of the Book of Numbers. Next week, we’ll begin our Lent Journey, as we make our way toward Easter. Our theme for our Lenten series will be “Busy.” It’s a timely series; we all struggle with busyness. As a way of catching our breath, we’re going to be encouraged by scripture to reconnect to an unhurried God. As a warning, we’ll be doing a few different things in worship. It’ll be exciting, so come and invite others who feel hurried in life to join us for a refreshing break each week as we gather on Sunday.

Little Tommy was riding in the backseat as the family came home from church. “What did you learn in Sunday School today,” his father asked.

Little Tommy was riding in the backseat as the family came home from church. “What did you learn in Sunday School today,” his father asked. Now back to Moses. He’s the face people see. And because they still aren’t sure what’s up, he’s the one who receives all the complaints. He’s weary and needs help. But unlike the people who have questioned God’s goodness, thinking the Almighty led them into the desert to die, Moses trusts the Lord. After all, God has always comes through. When Israel’s back was up against the sea, it wasn’t Moses who parted the sea. He might have lifted his arms as we see in the movies, but it was God, the one who watches out for Israel, who saves the day.

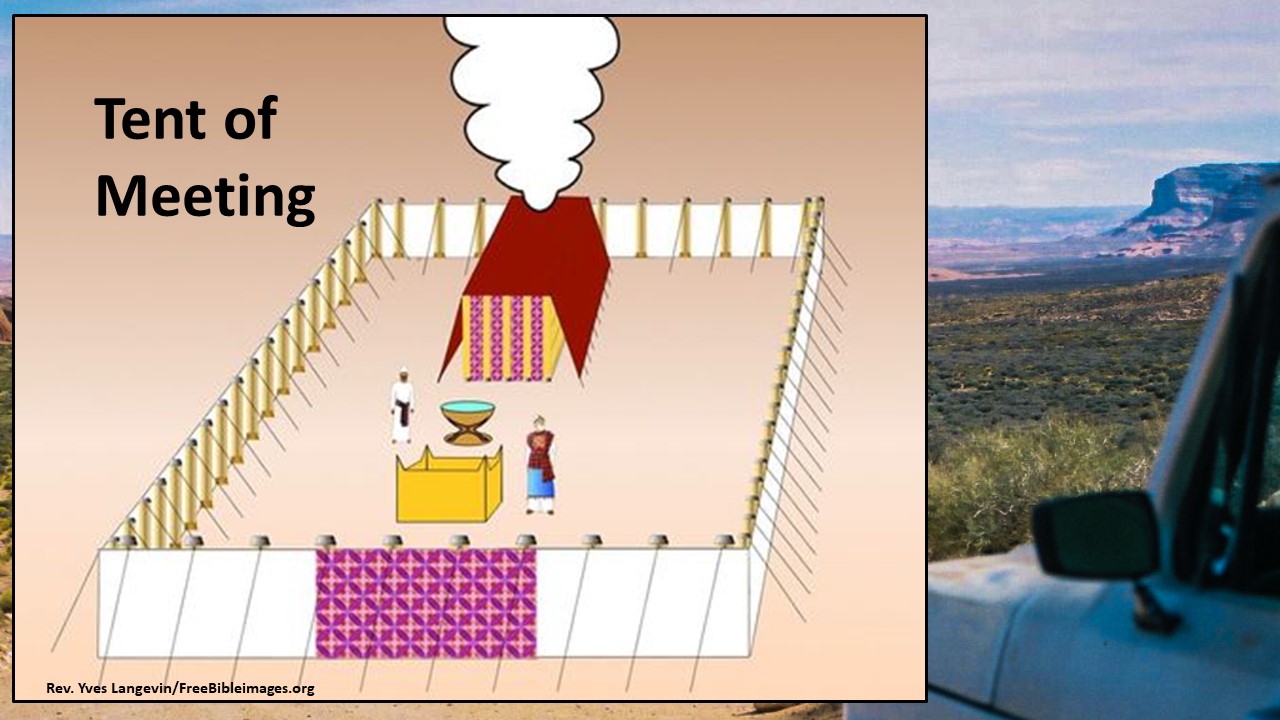

Now back to Moses. He’s the face people see. And because they still aren’t sure what’s up, he’s the one who receives all the complaints. He’s weary and needs help. But unlike the people who have questioned God’s goodness, thinking the Almighty led them into the desert to die, Moses trusts the Lord. After all, God has always comes through. When Israel’s back was up against the sea, it wasn’t Moses who parted the sea. He might have lifted his arms as we see in the movies, but it was God, the one who watches out for Israel, who saves the day. Let’s look at the text. After the elders were commissioned, they received the spirit and prophesied. That was all well and good, and expected. But what happens next is that there were two men, who were not in the assembly, who showed signs of having the spirit placed upon them. They, too, prophesied. This was disturbing, for these were not ones who were supposed to be doing this. A runner (a 14th Century BC tattle-tale) was sent to Moses saying, Eldad and Medad are prophesying in camp. Joshua was ready to have them stopped but it didn’t bother Moses. “Let them be,” Moses responded. “Are you jealous for me? Wouldn’t it be nice if all God’s people were prophets?”

Let’s look at the text. After the elders were commissioned, they received the spirit and prophesied. That was all well and good, and expected. But what happens next is that there were two men, who were not in the assembly, who showed signs of having the spirit placed upon them. They, too, prophesied. This was disturbing, for these were not ones who were supposed to be doing this. A runner (a 14th Century BC tattle-tale) was sent to Moses saying, Eldad and Medad are prophesying in camp. Joshua was ready to have them stopped but it didn’t bother Moses. “Let them be,” Moses responded. “Are you jealous for me? Wouldn’t it be nice if all God’s people were prophets?” What can we take from this passage? How might it apply to our topic of growth? There are two things that come to mind. First of all, as we see in the story of the Exodus, we have to take the risk to follow and to trust God. It can be scary at times, but if we are willing to take that risk, God will protect and watch over us. Faith isn’t about certainty; if it was, it wouldn’t be faith. Faith is about trust. Do we trust God enough to take a risk that will allow God to show us that he’s with us? When God’s church grapples at what its future might be, those who are willing to take a risk are the ones rewarded. It’s easy to sit back and do nothing, but that’s not the type of followers Jesus calls. As the Session of this church works on our strategic plan for the future (and this is a process), I hope you will be open to new directions. God calls us to risk in faith, not for our glory, but for God’s. Are we up for taking risks? We can’t keep doing the same thing that might have worked for us 30 or 40 years ago. Times change and new strategies are required. We are called to be people of faith and we must live into our calling.

What can we take from this passage? How might it apply to our topic of growth? There are two things that come to mind. First of all, as we see in the story of the Exodus, we have to take the risk to follow and to trust God. It can be scary at times, but if we are willing to take that risk, God will protect and watch over us. Faith isn’t about certainty; if it was, it wouldn’t be faith. Faith is about trust. Do we trust God enough to take a risk that will allow God to show us that he’s with us? When God’s church grapples at what its future might be, those who are willing to take a risk are the ones rewarded. It’s easy to sit back and do nothing, but that’s not the type of followers Jesus calls. As the Session of this church works on our strategic plan for the future (and this is a process), I hope you will be open to new directions. God calls us to risk in faith, not for our glory, but for God’s. Are we up for taking risks? We can’t keep doing the same thing that might have worked for us 30 or 40 years ago. Times change and new strategies are required. We are called to be people of faith and we must live into our calling. Secondly, we learn in this passage that we’re not in control and we need to let God’s Spirit work. Those who were upset with Eldad and Medad show a human tendency to have preconceived ideas of what it looks like when God shows up. We have to be ready for surprises, for God’s ideas may be different from ours. God has this incredible love for all people, not just those who look, think and act like us. We might be surprised what God is doing in our midst and it might make us uncomfortable. Someone might come up with a new idea that we’ve never tried before, or that was half-heartedly tried years ago. Is our first reaction to immediately reject it? Or are we willing to see if God’s Spirit’s is leading us in a different direction? The truth of Jesus Christ never changes, but how we live out that truth within a changing culture will be different.

Secondly, we learn in this passage that we’re not in control and we need to let God’s Spirit work. Those who were upset with Eldad and Medad show a human tendency to have preconceived ideas of what it looks like when God shows up. We have to be ready for surprises, for God’s ideas may be different from ours. God has this incredible love for all people, not just those who look, think and act like us. We might be surprised what God is doing in our midst and it might make us uncomfortable. Someone might come up with a new idea that we’ve never tried before, or that was half-heartedly tried years ago. Is our first reaction to immediately reject it? Or are we willing to see if God’s Spirit’s is leading us in a different direction? The truth of Jesus Christ never changes, but how we live out that truth within a changing culture will be different. Remember, it’s not about us. We’re called to have faith, to trust, and to follow Jesus as we move through the “Land Between.” And if we have faith, we will experience growth in our own lives and within the community. We might not know what that growth really looks like until afterwards, but when we are there, we will know that God has been with us. Amen.

Remember, it’s not about us. We’re called to have faith, to trust, and to follow Jesus as we move through the “Land Between.” And if we have faith, we will experience growth in our own lives and within the community. We might not know what that growth really looks like until afterwards, but when we are there, we will know that God has been with us. Amen.