Jeff Garrison

Bluemont and Mayberry Churches

December 11, 2022

Isaiah 35

At the beginning of worship

There is a wonderful little book filled with wisdom titled, Jacob the Baker. When teaching his fellow bakers, Jacob holds up his fist and says:

The fist starves the hand… When our hand is made into a fist, we cannot receive the gifts of life from ourselves, our friends, or our God. When our hand is closed in a fist, we cannot hold anything but bitterness. When we do this, we starve our stomachs and our souls. Our anger brings a famine on ourselves.[1]

Think about it. Harboring bitterness only intensifies our despair. We need to make the best of all situations.

Advent, as the days grow shorter, is a time of darkness. We might wish this time to quickly pass, but I suggest instead we seek God in such times. For only when we stand with open hands to receive the Lord will we be ready to be shepherded into a better place.

Before reading the scripture:

We’re again exploring a hopeful passage from Isaiah. This book forms the centerpiece for the Old Testament’s concept of a redeemer God. This is the God we meet fully in Jesus Christ, but the theological foundations for Christ’s work is set forth in Isaiah. Today, we look at the 35thchapter, which contains a hopeful vision.

Many scholars suggest chapters 34 and 35 should be read together even though they seem to be contradictory.[2] Chapter 34 deals with God’s judgment on the nations, with Edom particularly selected for condemnation. The land becomes a wasteland inhabited by wild animals. This desolation is followed, in Chapter 35, with the promise of God’s restoration. By the way, blending judgment and hope is something Isaiah does well.[3]

Read Isaiah 35

Life in the Desert

Life in the desert is precious. Everything fights for its share of water. Savage animals live in the desert; they must be that way to survive. They’ve adapted to the climate. The sidewinder rattlesnake jumps sideways as it makes its way across hot ground while only exposing a limited portion of its underbelly to the baking rock. Other snake who slithers on the ground can be quickly fried. They only come out at night and quickly find shade when the sun blazes.

Cactus is another example of unique survival. It’s a plant that stores up water and then defends its stash with sharp points. Everything competes for moisture.[4]

Fear of the desert

Many people are apprehensive about the desert. Back in 1988, when I moved to Virginia City, Nevada, I worried about driving across the 40-mile desert. I had read horrible accounts of what wagon trains endured crossing this parched land.[5] And it didn’t help any that I picked up a nail in a tire in Elko. Was this an omen? Thankfully, I was able to get the tire repaired in Lovelock, Nevada and made the trip without any problems.

Without air conditioning, water purification systems and deep wells, life in the desert is precarious. Today, it’s a bit easier, but you still don’t want to run out gas or water or with a flat tire.

In the days of Isaiah, the desert was even more hostile. Yet that’s where Israel finds herself, in the desert. Before looking at the 35th chapter, let’s take quickly review the 34th Chapter. As I’ve said, the two appear to be one unit.

The Judgment of Chapter 34

In the 34th Chapter, judgment has descended upon the world. Everything is affected. In the first four verses, we read of those slain by God’s anger. In verse five, we learn that Edom, a neighbor of Israel’s, is especially singled out for the harshest treatment. God’s wrath continues till only wild beast, demons, buzzards and the like, inhabit the land. The world is now a desert; it’s an inhospitable wilderness. There is no hope on the horizon.

Metaphorical deserts

So far, I’ve spoken about literal deserts, something that not all of us will experience. Those of us who do experience a real desert, will probably do it on our own free will and prepared. So, let’s think about deserts metaphorically. Yet, sooner or later, all of us will find ourselves in such a place.

Life becomes a struggle. We question what purpose life serves. It could be the evaporation of a career that seemed so promising. Or the unraveling of a marriage upon which we’d placed our hopes and dreams. The death of a parent, a child, or a close friend can bring about such feelings. Or our health declines, and things just don’t seem to be getter better. At such times, we enter a desert. We question if it’s worthwhile to continue to search for something that will quench our thirst. There’s no joy and no hope, only despair. Been there yet? Most of us have at least tasted a part of what I described. We’ve been there at the situation Isaiah explains in the 34 chapter, where hope seems as distant as a shower of rain in the summer desert.

But then we open the 35th chapter, which begins in the wilderness, and something strange happens. The wilderness and dry land we’re told are glad, the desert rejoices, flowers bloom abundantly.

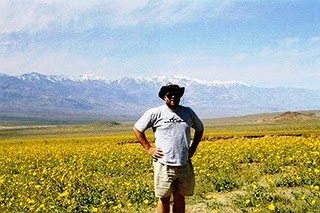

Death Valley in bloom

Occasionally, in late winter, Death Valley, one of the most inhospitable places in America, is transformed into a blanket of flowers. I once saw it in its full glory. This miracle last only for a week or two. It only occurs maybe once a decade, during a time where significant rain falls in December and January. Soon afterwards the flowers bloom, Death Valley resorts to its natural state. Everything dries up.

Isaiah and the desert blooming

I expect Isaiah experienced such wonder. He knew how things can change quickly. He knew how the desert can bloom and be transformed into a garden—how seeds lie in wait for a thirst-quenching rain. And Isaiah uses this vision to remind his readers that God does wonderful things. It’s not all judgment and despair. God works best in our wildernesses—transforming a barren landscape into one of life! Out of the crucible of judgment God leads his people.

Christ brings hope

This poem of Isaiah, which speaks of God’s people returning to Zion, foretells of Christ’s coming into a world without hope and reversing the fortunes of those with the least amount of confidence—the blind, the deaf, the lame. Water appears as springs bursting forth in the desert, again reminding us of the living water Jesus promises.[6]

A highway to paradise appears. A safe road with no nails waiting to puncture a tire. Those willing to leave their past behind move into God’s future are invited to journey upon it. Even fools, we’re told, won’t get lost on God’s Road. They’ll be no danger lurking at the edges. Lions won’t prowl. Remember, as I pointed out last week, the Assyrians were identified as a lion. But in this new Eden, ravenous beasts will stay away from those “ransomed” by the Lord.

No reason to despair in the desert

The message of this passage is that being in the desert is no reason for despair. It’s in the desert we experience the full joy of our God. If we have such an outlook on life, such expectations, desert places won’t seem so frightening. Instead, we can enter such landscapes with a hopeful anticipation on what God can do for us and through us.

God can speak in the desert

Terry Tempest Williams, a Utah author who writes about the land, says this about desert:

“If the desert is holy, it is because it is a forgotten place that allows us to remember the sacred. Perhaps that is why every pilgrimage to the desert is a pilgrimage to the self. There is no place to hide, and so we are found.”[7]

Williams is onto something. When we are in the desert, be they real or metaphorical, we are exposed. We find we must depend upon the other and upon God. It may be that the desert is the only place quiet enough for us to hear God speak. When things go well, we’re too busy to be bothered. But when things fall apart and there’s no place to turn, then we hear. These are the moments God might speak to us. The desert helps us define what’s important.

Keillor’s story of life after a desert experience

Garrison Keillor, in his book Wobegon Boy, tells John Tollefson’s story. A cheerful young man, he leaves Lake Wobegon for the glitter of New York. John rises to the top, managing a public radio station and, with a friend, opens a restaurant. He’s got it all, it seems. Then comes the desert. He’s fired. The restaurant fails. You’d think his cheerfulness would wane, but during this desert time he realizes what he wants. For the first time in his life, he makes a commitment to love. The book ends happily with his wedding. John’s desert clarified his understanding of himself. [8]

We can’t just depend on ourselves in the desert

Ultimately, the desert reminds us that we can’t just depend upon ourselves. We must depend upon something greater, upon God. In Sacred Thirst: Meeting God in the Desert of our Longings, Craig Barnes points out that if we try to take care of every situation we find in our deserts, we’ll quickly burn up. We learn in the desert that Jesus, not anything we can do, is the answer.[9]

When we’re in a desert, we find we must listen and accept help from God and others to find the way out.

While I don’t wish adversity on anyone, during such times if we choose, we might experience God. That’s the hope of Christmas. Don’t fear the deserts that may be before you, instead look at them as opportunities. Expect great things from our God. Amen.

[1] Noah BenShea, Jacob the Baker: Gentle Wisdom for a Complicated World (NY: Ballantine, 1989), 27-28.

[2] Christopher R. Seitz, Isaiah 1-39: Interpretation, A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1993), 236.

[3] I was reminded of this reading Fleming Rutledge’s sermon on Isaiah 64 and 65 titled, “Advent on the Brink of War” in The Once and Future Coming of Jesus Christ (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018), 307-309

[4] For a good understanding of water in the desert, see Craig Child’s The Secret Knowledge of Water (Sasquatch Books, 2000).

[5] The summer before moving to Nevada for a year as a student pastor, I worked at a camp in the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho. One of the books I read that summer, in preparation for going to Nevada, was Sessions S. Wheeler, The Nevada Desert (1971, Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1972). Chapter 2 is titled “The Dreaded 40 Mile Desert.” This is a section of land between Lovelock and Reno (the Humboldt Sink and the Truckee River) where there is no water to be found.

[6] John 4:10, 7:37-38.

[7] Terry Tempest Williams, Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place (New York: Vintage, 1992), 148.

[8] Garrison Keillor, Wobegon Boy (New York: Viking, 1997).

[9] M. Craig Barnes, Sacred Thirst: Meeting God in the Desert of our Longings (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001), see especially Chapter 5. Barnes draws heavily on the story of the Samaritan woman at the well found in John 4.

That’s me standing in Death Valley in early March of 2005.

The photo of Death Valley in bloom is wonderful, Jeff. It reminds me of a time in the early 1990s when Terry and I saw the desert in bloom around Palm Springs. It is astonishing to see all the gorgeous flowers. I have always loved the desert. You wrote, “It may be that the desert is the only place quiet enough for us to hear God speak.” There is so much truth in that statement. Our noisy busy lives drown out that voice of God. I, for one, need to get out into the silent wilderness to truly hear.

I find Death Valley fascinating and there is much to learn in deserts!

I’ve been to Death Valley a few times. We try not to go in the middle of the Summer though in case the car breaks down. Don’t want to be stuck out there in that heat.

I’ve only been to Death Valley once in the summer–124 degrees F–but I’ve been there in late February when the temperatures rose to 100. It’s not a place you’d want to have car trouble.

That quote from Jacob the Baker is wonderful. I’m going to have to share that…

it’s a delightful and very quick read