The weather has often been cold and unpleasant, so I have been doing a lot of reading. These five books are all different, so maybe you’ll find something that is of interest. I often read something in February in honor of Black history. I have been reading His Truth is Marching ON: John Lewis and the Power of Hope by Jon Meacham. But, I won’t finish this book before the end of the month. Look for the review next month.

Stanley Hauerwas, Hannah’s Child: A Theologian’s Memoir

(Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 2010), 288 pages, no illustrations.

One of the first books I remember reading after my ordination was Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony by Stanley Hauerwas and William Willimon. The book came out during my last year in seminary, and I borrowed a copy for the presbytery office. I liked the book so much that I ordered a copy for myself and reread it. I often go back to that book, and it has informed my ministry over the past 35 years. Beside that one book, I have only read articles by Hauerwas. Learning that he had a memoir, I decided to read it. While this reads more like an autobiography than a memoir,[1] I’m still glad that I read it and recommend it to others.

Hauerwas was the son of a bricklayer. His parents were modest lower middle-class Methodists from Texas. Both parents were older when he was born and his mother, like Hannah the mother of Samuel in the Old Testament, promised to dedicate her son to the Lord. Hauerwas sensed this and even committed his life into that direction, which led him to college and on to Yale Divinity School. But instead of becoming a pastor (he was never ordained and wasn’t even sure, at first, he was Christian), Hauerwas went on to earn a PhD focusing on ethics. He spent his career teaching and writing.

Hauerwas began teaching at Augustana, a small Lutheran College. After two years, he moved to Notre Dame, where he taught for fourteen years, and then on to Duke Divinity School. Throughout this time, the nation dealt with Civil Rights and Vietnam. In his memoir, he is also honest about the political struggles in academia. This was especially true at Notre Dame, where he was a Protestant teaching in a Roman Catholic university.

Another intimate part of the book deals with his first wife, Anne, who had mental health issues that showed up early in their marriage and increased over time in severity. Bipolar by nature, Anne struggled with reality. She often thought she was in love with other men (who she fantasized as loving her) and much of this first marriage was without sexual intimacy. Along the way, they had one child, Adam, who was mostly raised by Hauerwas. After moving to Duke, Anne decided she wanted to go back to South Bend (where she was again in love). They divorced and her world unraveled. In her 50s, she died of a heart attack.

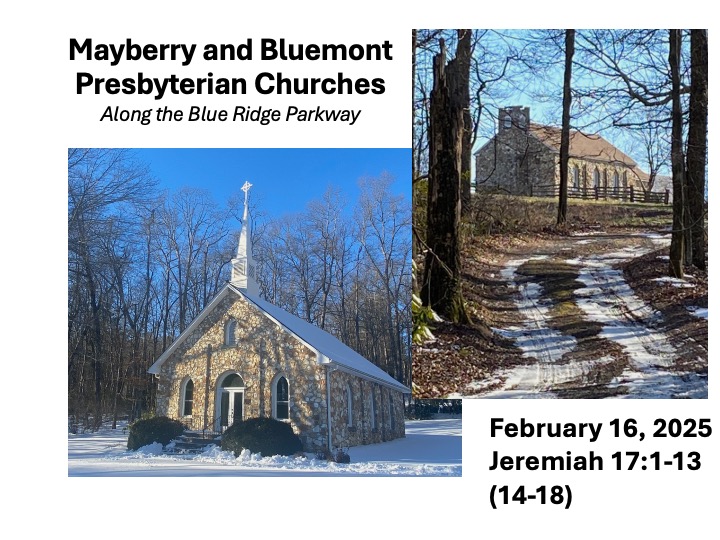

Hauerwas then married Paula, a woman who was working at Duke and an ordained Methodist pastor. According to his story, their relationship has been much steadier, and both have been able to thrive in their relationship with each other and others in the academic community. They also both love baseball and at one time (before I moved to the Blue Ridge) owned a house on Groundhog Mountain, which I pass every Sunday morning between Mayberry and Bluemont.

One of the things I appreciate about the book are details about who have influenced Hauerwas. Early on, it was Barth and the Niebuhr brothers. Later came Catholic theologians and a Mennonite, John Yoder, who helped Hauerwas move toward Christian pacifism. In addition to those Hauerwas personally knows, he also credits books which have helped shape his theology. There is much in this book for those who enjoy theology, philosophy, and how thought process is shaped.

[1] I think of a memoir as focusing narrowly on one aspect of a life. This book tends to focus on many aspects of the author’s life, from his birth to his sixties.

Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons for the Twentieth Century

(New York: Crown, 2017), 127 pages.

This is a valuable little book that shouldn’t take most readers more than an hour or two to read. I’ve heard it mentioned often lately as an antidote (or resistant manual) to a more authoritarian society which seems to be preferred by many in the western world. As for the desire for authoritarian desires, see Anne Applebaum, The Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism.

Snyder offers easy to understand lessons on how we might resist tyranny. The first one has become a rallying cry since the election, “Don’t Obey in Advance.” The lessons themselves are just a few words, making them easy to understand. Then, following each lesson is a bolded paragraph highlighting the importance of such action. This is then followed by several pages of examples from European fascist movements early in the 20thCentury and the collapse of Eastern Europe into the communist domain following World War 2. Snyder also highlights the troubling trend of many of these same countries, after having a short bit of freedom with the collapse of the Soviet Union, have slipped back into authoritarian control.

The Twenty Lessons:

- Do note obey in advance

- Defend institutions

- Beware of the one-party state

- Take responsibility for the face of the world

- Remember professional ethics

- Be wary of paramilitaries

- Be reflective if you must be armed

- Stand out

- Be kind to our language

- Believe in truth

- Investigate

- Make eye contact and small talk

- Practice corporeal politics

- Establish a private life

- Contribute to good causes

- Learn from peers in other countries

- Listen for dangerous words

- Be calm when the unthinkable arrives

- Be patriot

- Be as courageous as you can

I especially liked his lesson on being kind to our language. Here, he encourages us to read books (not just what’s on the internet). His reading list includes:

*Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 45

*George Orwell, *1984, *Animal Farm, and his wonderful essay, *“Politics and the English Language”

*Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

*Sinclair Lewis, It Can’t Happen Here

Philip Roth, The Plot Against America

Victor Klemperer, The Language of the Third Reich

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

Albert Camus, The Rebel

Czeslaw Milosz, The Captive Mind

Vaclav Havel, The Power of the Powerless

Timothy Garton Ash, The Use of Adversity

Tony Judt, The Burden of Responsibility

*Christopher Browning, Ordinary Men

Peter Pomerantsev, Nothing is True and Everything is Possible

J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

The * indicates books I’ve read (8 out of 18, so I have some catching up to do).

This is an important book. It might be a good one for a small group of people to read together and to discuss, over a period of time, each of the lessons.

Leo Damrosch, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age,

narrated by Simon Vance (2019, Audible, 15 hours and 1 minute.

In 1763, the English portrait painter Joshua Reynolds proposed to Samuel Johnson to start a club that would meet each Friday evening. Starting with nine members, the club voted on new members (and membership had to be approved by all members allowing one no vote to blackball a prospective member). While this book focuses only on the activity of club members in the 18thCentury, the club continues to this day as the London Literary Club. For most of the 18th Century, The Club met at the Turk’s Head Tavern, starting with dinner at 6 PM, and then drinks and conversation going on till midnight (or afterwards).

The membership of the Club in the early years were men (the membership was all male), who made their mark on history. In addition to social critic Samuel Johnson and biographer James Boswell, The Club had an impressive list of members. Reynolds made a fortune with commissioned portraits. The great political philosopher Edmund Burke, who is best known for his quote, “All that is required for the triumphant of evil is for good men to do nothing,” was a member. He still influences true conservative thinkers today. Sadly, most who consider themselves conservative probably don’t know him, the exceptions being George Will and Arthur Brooks. Another Scottish political philosopher, Adam Smith, gave us economics as a discipline. Edmund Gibbons wrote the multi-volume Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Other members included David Garrick, the great Shakespearean actor who changed the way actors performed, and playwright Oliver Goldsmith.

While each of the above members receive a short biography within the book, Damrosch focuses most on James Boswell (who joined The Club after its establishment) and Samuel Johnson. Johnson was English and Boswell was Scottish and would later become the Lord over a vast estate upon his father’s death. Boswell also wrote a major biography of Johnson. The two of them even took a Scottish holiday, traveling across the lowlands and to the Inner Hebrides. Both would published books on the journey.

Johnson valued the control of one’s passions while Boswell often drank to excess and sought out prostitutes. In Boswell’s journals he used codes, which have been broken, to indicate sexual activity. Boswell had a rough relationship with his father. Johnson who was 20 years older than Boswell, became a surrogate father for him while he was in London.

Damrosch dedicates some focus to what was going on in the larger world during this era, from the Seven Years War (known as the French and Indian War in America) to the American and French Revolutions. Club members discussed topics such as capital punishment, slavery, and religion.

While I have listened to this book, I have also ordered a copy because I want to go back and collect quotes. Also, the text often refers to paintings of the era which was printed within the book. I recommend it.

J. Murray, To Hunt a Sub

(Laguna Hills, CA: Structured Learning LLC, 2016), 370 pages.

I picked this book to read because it was about submarines. For some reason, my daughter has been fascinated with submarines and I partly to be able to keep up a conversation with her, I have read several books on submarines over the past several years. I also chose this book as I have followed Jacqui Murray’s blog for years and wanted to read one of her books.

However, if you’re looking for a book on submarines, this isn’t your book. Only a few pages of this story deal up what happens in a submarine. In this case, the sub has lost control due to a computer virus. The story is engaging. It reminds me of some of the action books I read in high school.

To Hunt a Sub centers on an Islamic terrorist group who figured out a way to incapacitate the American submarine fleet. To pull it off, they need the help of an Artificial Intelligence research of Kali Delamagente, a single parent PhD candidate at Columbia University. Her research blends AI, geography, and paleoethology. Her computer program named Otto allows her to go back in time to places where she follows “Lucy” around as she and her tribe made their way out of Africa tens of thousands of years ago. This story is very creative, blending life in the “pre-human world,” paleoethology, computer science, geo-positioning and terrorism.

Center to the story is Kali, who is running of out of funds and time to finish her research and complete her degree. Two shady men attempt to help her, but for their own benefit. One is a male professor who secretly kill off lovers and stole their research, which he published as his own. The other is a Muslim on a secret jihad. Kali’s research will help him in his goal to kill large numbers of “infidels.” He promises money for her research.

Helping Kali avoid the dangers she faces is Zeke Rowe, an ex-Navy Seal, whose last mission resulted in permanent disabilities. He is now a professor of paleoanthropology at Columbia but has been secretly recruited by the Navy to help them discover what’s going on with the submarine fleet. The two are romantically drawn to each other, but both put the importance of their work ahead of any relationship. In addition, Kali is not just concerned for her well-being but that of her son and her three-legged dog.

The book was a fast read as I was drawn into the story. There’s lots of action and plenty of violence, but in the end the good guys win, and the American fleet is safe. The number of characters (and how some of them used various names in different settings), was confusing until I got further into the story. Some of the encounters seemed far-fetched. But this is an action book and it keeps your attention.

Fred Chappell, River: A Poem

(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1975), 51 pages.

This is a delightful collection of poetry by the late Fred Chappell, who taught at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro for forty years and served four years as Poet Laurate for the state of North Carolina. Originally from Canton, North Carolina, these poems draw heavily on the image of the mountains. River was Chappell’s second book of poetry. In addition to poetry, Chappell has also published novels and short stories.

While the title suggests the book is “a poem,” it consists of 13 rather long poems. Some like “Susan Bathing,” are prose-like. This poem describes in detail but without slipping into pornography his wife’s body. Another, “Science Fiction Water Letter to Guy Lillian takes on the form of a poetic letter. Others are more traditional, often drawing on stories of his grandparents. One moving poem, “Dead Soldiers,” is about the floods in 1944 and the empty liquor bottles in a man’s basement which are washed down the river as he shoots at the bobbing bottles with a 22 rifle. Reading it brought the floods in the mountains after Hurricane Helene last year to mind. The poems capture the rough life many in the mountains endured.

Water, more than rivers, provides a unifying theme of the poems. While rivers often show up, but so does water such him as a child being lowered into a well to clean it. Other water themes include bathing and baptizing. The poems draw on Appalachian sayings and include clever phrases and metaphors. Humor is also inserted into the poems.

I found similarities in these poems and Wayne Caldwell’s Woodsmoke, which I read last year and Ron Nash’s, Among the Believers, which I read several years ago but didn’t review. I recommend this book especially for someone wanting to capture the sense of the mountains in the early 20th century.