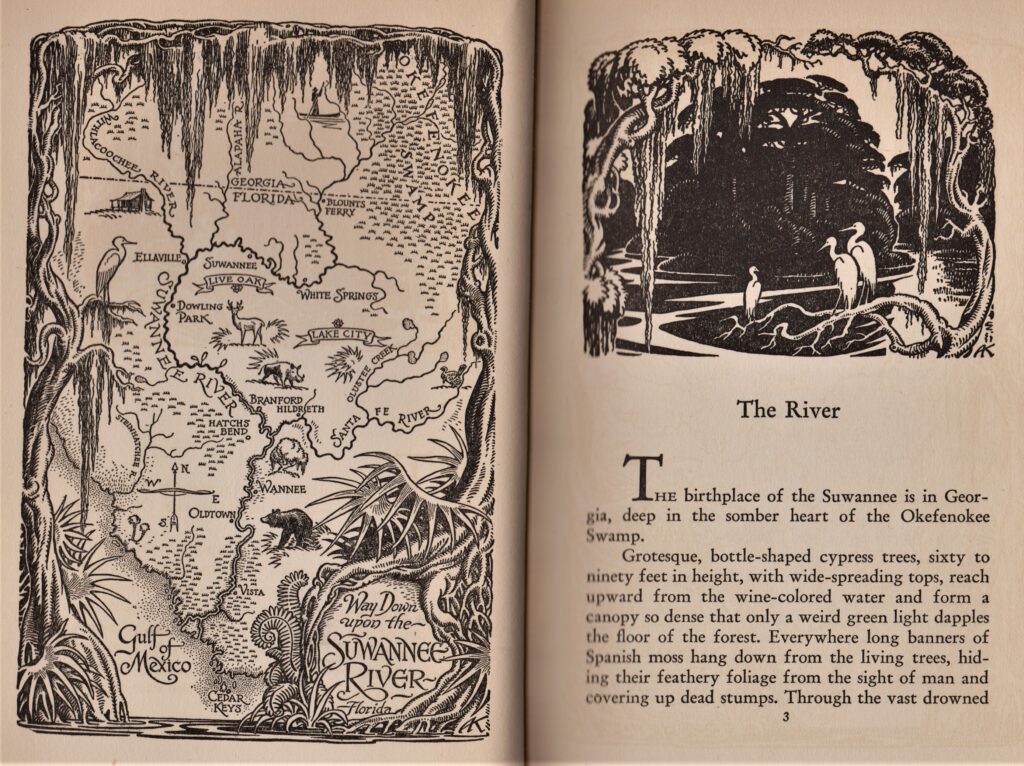

Cecile Hulse Matschat, Suwannee River: Strange Green Land, A Descriptive Joureny through the Enchanted Okefenokee (1938, 1966, Athens, GA: University Press, 1980), 296 pages including a bibliography, glossary, bird and flora list, an index. Black and white drawings illustrate each chapter.

I picked this book up at a used bookstore several years ago. It was the perfect book to pack along on my recent ramblings in and around the Okefenokee. Originally published in the late 1930s as a part of a “River in America” series, the University of Georgia Press republished it

I have read many books about rivers. I enjoy an author taking me down a steam, telling me about the river, its history, along with the flora and fauna and wildlife around its water. This book does that in a fresh and unique manner. The author, an “outlander” from New York. She, heads into the Okefenokee Swamp looking for the headwaters of the Suwanee River in the 1930s. Drawing on her interest and knowledge of plants, she becomes known as the “Plant Woman,” and gains the confidence of the people who live in the swamp. She then writes about the swamp and river through the eyes of the native residents of the swamp. Not only will the reader learn about the region’s natural history but also gains an appreciation of the stories of the swamp. These stories are told in the swamper’s own dialect.

The largest part of this book involves the Plant Woman’s stay with those living in the swamp. Here, we also learn the folk heritage of the swamp. Instead of a scientific understanding of the region, we learn of how the beavers and the native people had developed a truce, but when a new chief rose, he decided to make war on the beavers. In retaliation, the beavers flooded the land and abandoned it forever (there are no beavers in the swamp. We learn of tall tales of the ingenuity of who lived in the swamp. One “swamper” wedded bees and lightening bugs, doubling his production of honey because the insects could now work 24 hours a day.

Matschat asks to see a still. They blindfolded her and take her by boat to a remote landing. There, she sees a still in operation and learns about moonshine. She introduces us to the “snake woman” who has a pet kingsnake. Some of boys catch a large rattlesnake with 21 rattlers They set up a fight with the kingsnake. Everyone knew the kingsnake would win, but the betting was on how long the rattlesnake could last against its arch enemy. She’s present as they boil off cane squeezings into syrup and learns about “old Christmas.” She tells of people’s encounter with the wilds. This included wild hogs, bears, and sandhill cranes. We also learn how they cared for each other. We are provided with recipes for delights like sweet potato biscuits along with the words to songs sung to pass time. Her time in the swamp ends with a wedding.

After her time in the swamp, she takes boat down the Suwannee River. Here, she experiences a variety of orchids and meets those who live by the river. She spends some time on old cotton plantations, with African Americans left behind after the Civil War. There, they eke out a living from farming, hunting, and fishing. Some may find this section difficult as Matschat tells of older members speaking fondly of slave days. This doesn’t ring politically correct today, but she found the former slaves still living in their cabins as the old mansions of the masters were rotting away and considered haunted.

One of the stories an old man tells the children is about the rabbit. Supposedly, the rabbit used to have a beautiful long tail. Noah’s son, Ham, in the ark, spent his time during the rain playing the banjo. When his strings broke, Noah suggested he take the tail of the rabbits to create new strings. He did, which is why rabbits now have bobbed tails.

When she gets to the mouth of the Suwannee, she takes a boat down to Cedar Key. There, she meets a more international community of Cuban and Portuguese fishermen and hears more tales of pirates and hurricanes. She leaves her journey behind, taking an airplane from Cedar Key back north. For all her journey, you’d thought she was in the 19th or 18th centuries. Only here at the end we’re reminded that her experiences were in the 1930s. I found this a delightful book and highly recommend it if you can find a copy.

If one wants to learn more about the actual history of the Okefenokee, I suggest reading Trembling Earth. I first reviewed it in 2015 and have republished my review below. It’s academic and approaches the swamp’s folklore from a more objective perspective. She of how it was a refugee for runaway slaves, native Americans, deserters during the Civil War, and outlaws. She also tells of human efforts to drain the swamp, which became a folly.

Megan Kate Nelson, Trembling Earth: A Cultural History of the Okefenokee Swamp (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005), 262 pages including notes, index, bibliography, and a few photos.

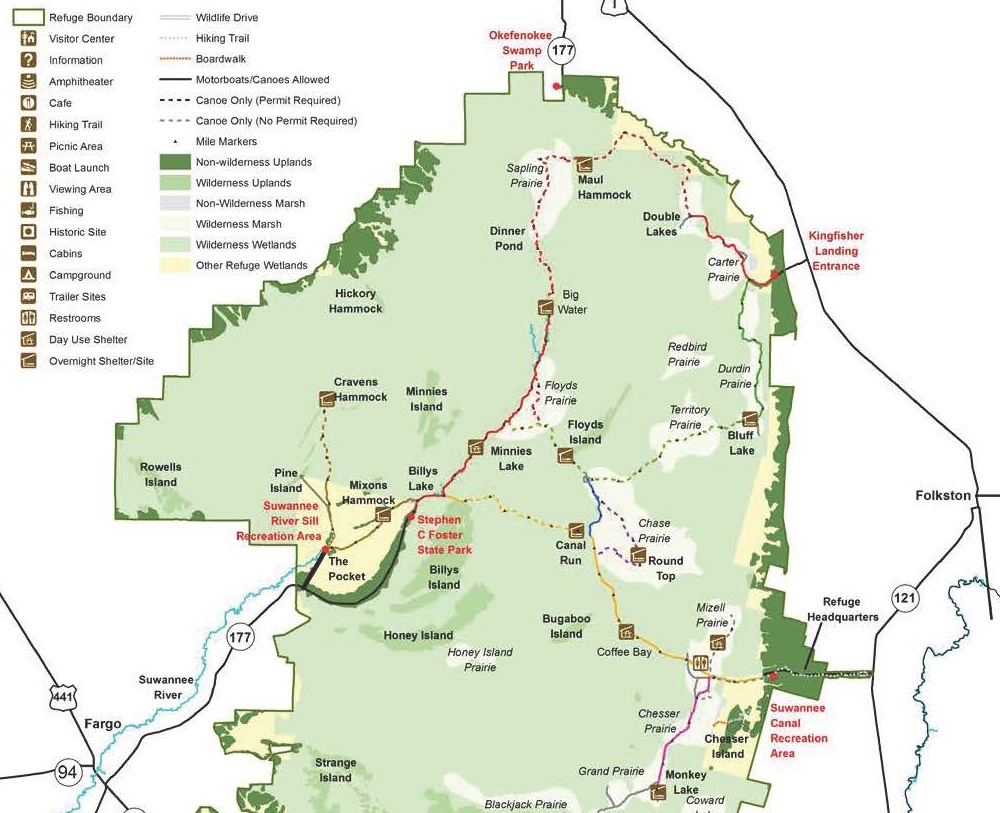

The Okefenokee Swamp is huge bog located mostly in South Georgia, just above the Florida border. Today, much of it is a National Wildlife Refuge. Prior to this status, the swamp existed as a barrier. Nelson calls it an “edge space.” The name, “Okefenokee,” comes out of a Native American term meaning “trembling earth.” This name describes the floating peat islands inside the swamp. Since there is only a little “solid” high ground inside the swamp, few made their home there.

Prior to European immigration, there were a few native communities existing along the edges of the swamp. The interior was only probed for hunting. This changed over time as the Spanish began to populate Florida and the British began to move into Georgia. The swamp and the native populations served as a buffer between British and later Americans in the north and the Spanish in the South.

Native communities began to move into the swamp during the Seminole wars of the early 19th Century, using it geographical barrier to their advantage. Another group to find the interior of the swamp beneficial were runaway slaves. At first, Georgia didn’t allow slavery. However, Africans had some immunity to the diseases that affected Europeans. That, along with the need for new areas to expand rice plantations , a push was made to extend slavery. Being close to Spanish Florida, some slaves would hide out in the swamp before making their ways south. Interestingly, the last group to find refuge in the swamp were poor white men. At first, they avoided conscription in the Confederate army during the Civil War by hiding in the forbidding swamp. Later, “crackers” who lived under the radar in the swamp, living off the bounty of the land.

After the Civil War, serious attempts were made to “conquer” the swamp. The first was a failed attempt to drain the swamp through the St. Mary’s River to the Atlantic Ocean. It was with hopes that the rich ground could be utilized for farming. This attempt failed to understand the geography for most of the swamp drains through the Suwanee River into the Gulf of Mexico.

After the bankruptcy of the dredging company, the swamp fell into the hands of northern timber companies who built “mud lines” (temporary railway spurs) which allowed them to harvest much of the cypress and pine within the swamp. During this time, another group began to make the swamp their home. These “crackers” or “swampers,” both worked for and often resisted the various dredging and timber companies who attempted to change their environment. As the timber was being harvested, the interest in birdlife in the swamp increased as various surveys were made of the birds and waterfowl within the swamp were taken. This lead to the creation of a government protected wildlife refugee in the 1930s.

Using a historicity which she labels “ecolocalism,” Nelson tells the history of the swamp through the stories of competing groups who relate to the landscape in different ways. These groups include Native Americans, slaves, colonists, developers, swampers, scientists, naturalists and tourists. This book is a distillation of the author’s dissertation. Although edited into its present form, it still maintains an academic distance from her subject. Only in an opening essay does she acknowledge having been into the swamp. This lack of a personal connect makes the book seem a little aloft. She does draw upon many of the group’s stories which makes the book very readable.

We eat lunch under the front porch during a downpour. A turkey and a fawn with spots make their way through our camp as we wait for the rain to clear. Later in the afternoon, when the storms have cleared, we move our kayaks, portaging over the quarter mile or so of the island, so that we’d be ready for the next day’s paddle. That evening, we cook over an open fire. The smoke helps deter the biting flies. We enjoy crackers and cheese, party nuts, along with some Johnny Walker Black Label. Again, I’m impressed with Gary’s beverage selection. I’m saving my cheap bourbon. Tomorrow, Gary will paddle out of the swamp while I will stay for another night.

We eat lunch under the front porch during a downpour. A turkey and a fawn with spots make their way through our camp as we wait for the rain to clear. Later in the afternoon, when the storms have cleared, we move our kayaks, portaging over the quarter mile or so of the island, so that we’d be ready for the next day’s paddle. That evening, we cook over an open fire. The smoke helps deter the biting flies. We enjoy crackers and cheese, party nuts, along with some Johnny Walker Black Label. Again, I’m impressed with Gary’s beverage selection. I’m saving my cheap bourbon. Tomorrow, Gary will paddle out of the swamp while I will stay for another night.

It’s good that we didn’t explore because after the turn-off to Double Lakes, the trail becomes more difficult. In places, lily pads and other weeds fill the channel and often seem to grab and hold on to your paddle. It’s a workout, but we keep paddling. The lily pads include the elegant blooming white lotus plants and some of the more bland yellow blooms. Along the sides of the path, where it is open, are hooded pitcher plants, purple swamp irises and pickerel weed with its purple torch-like flowers. At places, bladderworts, odd flowering plants that grow in water, are seen. Like the pitcher plants, they too are carnivorous. With so many insect eating plants, you’d think bugs wouldn’t be a problem. The abundance of these plants are an indication of the poor soil, so they have evolved to obtain nutrients from other sources. And there seems to be plenty of mosquitoes and biting flies to feed these plants, as we’ll later experience.

It’s good that we didn’t explore because after the turn-off to Double Lakes, the trail becomes more difficult. In places, lily pads and other weeds fill the channel and often seem to grab and hold on to your paddle. It’s a workout, but we keep paddling. The lily pads include the elegant blooming white lotus plants and some of the more bland yellow blooms. Along the sides of the path, where it is open, are hooded pitcher plants, purple swamp irises and pickerel weed with its purple torch-like flowers. At places, bladderworts, odd flowering plants that grow in water, are seen. Like the pitcher plants, they too are carnivorous. With so many insect eating plants, you’d think bugs wouldn’t be a problem. The abundance of these plants are an indication of the poor soil, so they have evolved to obtain nutrients from other sources. And there seems to be plenty of mosquitoes and biting flies to feed these plants, as we’ll later experience.