Kungur, Russia, Late July 2011

I arrived in Kungur early on Sunday afternoon, the day before, after traveling three days on the trans-Siberian from Ulan Ude, west of Lake Baikal. That afternoon, I took a tour of the city and asked the guide about church services. At the Tikhvinskaya Church, she learned there would be services the next morning which would include baptisms. On Monday, I was there shortly after the doors opened. This church had only recently resumed being a church. During the Soviet era, the government converted the church into a prison.

When I arrived, only a handful of people were in the church. Mostly, the congregation was made up of older women, but I did notice one man who was about my age and who seemed as clueless as me when it came to Orthodox traditions. As is custom, we all stood. However, around the edge of the massive sanctuary, there were a few benches and at times, some of the women would go sit down for a break. Much of the service consisted of alternating chanting from the balcony (done by a man and a woman) and from behind the icons (done by a priest). The entire service, except for a few readings, was sung without accompaniment. Not speaking the language, I was mostly clueless as to what was happening. But the building and the voices were beautiful, and I just took it all in.

I had been there about an hour when a man entered the sanctuary and approached me, speaking in Russia. At first, I wondered if he was a beggar, looking for money, but he was too well dressed for that. He got into my face, and I smelled alcohol. He seemed distraught. I shrugged my shoulders and whisper that I don’t speak Russian. After a few minutes, he left and walked over to a window where there were numerous candles. He lighted a candle and stood for a few minutes. Then he turned around and headed over to me and in perfect English said, “I’m sorry, my father died this morning.” Caught off guard, I expressed my condolences and asked if I could pray for him. “Yes,” he said. I placed by hand on his shoulder and prayed. “Thank you,” he said, as he turned and left the sanctuary. I never saw him again.

A little later in the service, the priest opens the door through the icons and prepares communion. I debated taking communion, if offered. A few people went over to receive the bread, but most did not, so I remained where I was at. Then, an older mousy woman who’d been helping with things brought me a piece of the bread and offered it to me. I wasn’t exactly sure what it all meant, but I decided that communion is at best a mystery and the polite thing to do was to be gracious. Humbly bowing my head, I accepted the bread from the woman, held it for a moment while I prayed for her and for the congregation who welcomed me, a stranger.

After communion, a man and woman with an infant that looked to be maybe 6 or 9 months old, walked up to the priest and presented the child. From a distance, it appears the priest gave the child a piece of bread soaked in the wine. I couldn’t really see the baptism. Then there were prayers said over the child and each parent lighted a candle, then left. After some more chanting in Russia, the service ended. It was nearly 11 AM and I ran back down the hill to the hotel and checked out and headed to the train station for my next leg of the journey.

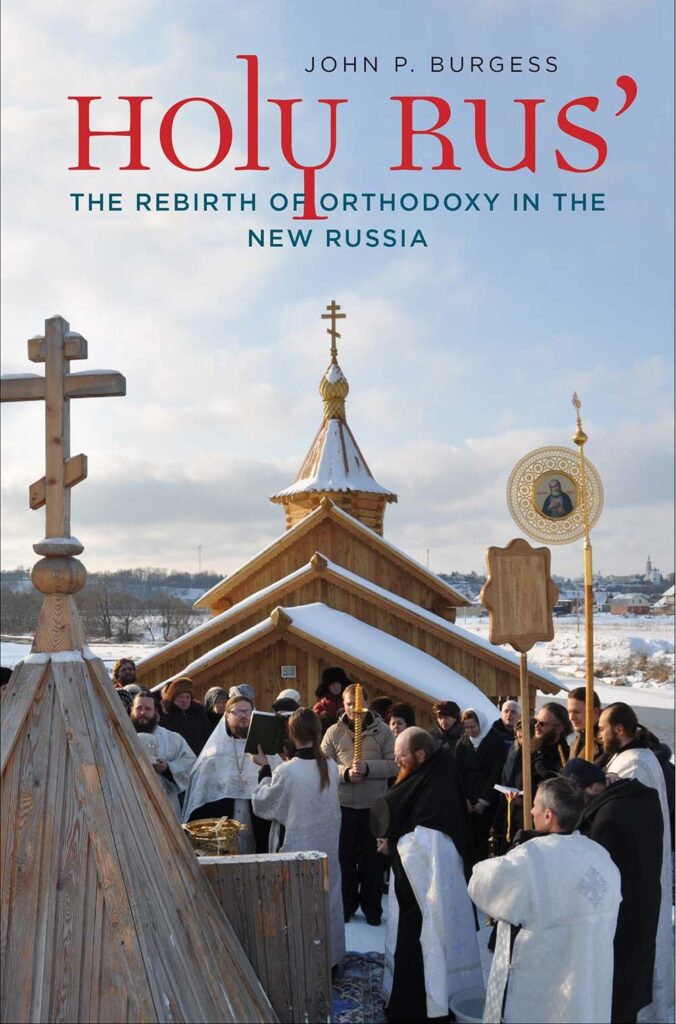

John P. Burgess, Holy Rus’: The Rebirth of Orthodoxy in the New Russia

(New Haven, CT: Yale, 2017), 264 pages including index and notes. Some photographs.

Burgess, a theology professor at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, spent several sabbaticals in Russia learning about the Russian Orthodox Church. He worshiped in Orthodox Churches, attended Bible Studies, befriended members and priests. While Burgess roots are in Reformed Tradition, his inquisitive and open mind provides a unique insight into the Orthodox tradition.

While Burgess goal is not to give the reader a history of the Orthodox tradition in Russia, he does provide a history of the church in the 20th Century,. Much of this decade, the church lived under a dictatorial communist regime who sought to exterminate religion in Russia. The church struggled to survived as the government converted the church’s property into museums, theaters, and even prisons. The early years were the worse. The church strove to survive by supporting the government as they followed the Apostle’s Paul’s commands. During World War II, even Stalin saw the church as useful in the defense of the nation and the worse persecutions waned. But it wasn’t until the 90s, after the breakup of the Soviet Union, that the church was free to openly participate in society. Much of the book explains the rising role of the church during this era.

Holy Rus is a vague concept that see’s the Russian Church link to the nation for the purpose of the advancement of the gospel. While the idea was established during the age of the Czars, it has found its way back into the mainstream. Putin has embraced such ideology as he attempts to place Russia, and not the West, as carrying on the gospel traditions. While Burgess doesn’t say so, Holy Rus to me seems to be a Russian version of Christian Nationalism.

While this book attempts to explain the role of the church in modern Russia, it also part travelogue. Burgess takes us along with him as he travels Russia and meets with leaders and priests and laypeople within the church. This is a valuable book for those looking to understand the Orthodox Church’s role in modern Russia, but because of the expanded war in Ukraine, I sensed that the book was a little dated.

I picked up this book at the Theology Matter’s Conference I attended last month in Hilton Head. Burgess was one of the presenters. I have previous reviewed his book, After Baptism: The Shaping of the Christian Life.

Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History

(2003, audible published in 2004), 27 hours and 41 minutes).

This Pulitzer Prize winning book has been on my TBR list for several years. I have previously read two of her books: Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine and Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism. Both books seemed more important to understanding the world we live in than old Soviet history. However, a few weeks after I finished this book, Mike Davis, of Trump’s lawyers mused about building Gulags for liberal white women. Sadly, I realized it might be a good thing I have some knowledge of what he was talking about. Gulags aren’t necessarily tied to communism. They’re tools totalitarians use to create fear within society to keep people in line. In the old Soviet Union, any minor infraction could end you in a Gulag, which helped maintain control over the masses.

I started listening to his book in early October, knowing I had long road trips ahead in which I could listen to large sections of the book (I drove to Hilton Head, SC, then to Wilmington, NC, and then home). With over 15 hours in the car, and my regular walks, I was able to finish the book in less than two weeks.

Applebaum begins discussing how the Gulag took shape from the beginning under Lenin and on through the 70s and 80s. Over the course of the decades, the Gulag changed. Lenin used the prison system to put away “enemies” who had different ideas about government. This included many communists who saw things differently. One of the interesting things about the Gulag is that many of the prisoners remained loyal to the Soviet ideals. Early on, the Gulag was seen as a way for economic gain. Attempts to profit from prison labor included building the White Sea Canal and lumbering in the north and mining in the vastness of Siberia.

Stalin took the Gulag into more extremes and in the late 30s, during his purges, the most horrific atrocities occurred (both within the Gulag system and general executions). During World War 2, the Gulags in the east had to be moved to avoid capture by the Germans. Some prisoners, unable to be moved, were summarily executed. Applebaum spends some time discussing the differences between the Soviet Gulags and the Nazi Concentration Camps. As bad as the Gulags were, at least the Soviets weren’t attempting genocide against a particular race of people.

After the war, life improved slowly in the Gulags and things never returned to how bad it was in the late 1930s. However, many captured Soviet soldiers found themselves, upon being released from German POW camps, in the Gulag. Upon Stalin’s death and Khrushchev obtaining power, things slowly improved. But still, the camps continued to the fall of the Soviet Union.

One of the surprising things about the Gulags were the corruption, both by the camp leadership and the prisoners. Gangs often ruled the prisoners, especially those prisoners who were in the system due to criminal (as opposed to political or religion) crimes. These gangs terrorized other prisoners and sometimes even the guards.

The Gulags were also a training ground for those who would eventually lead to the breakdown of the Soviet system. The non-Russians often created their own gangs and many of those within the prison system learned leadership skills they would use to help throw off the communist governments in Poland, Ukraine, the Baltic States, and Georgia. In this way, the abuses of the Gulag created a time-bomb which helped undo the Soviet Union.

This is a long book, but worthwhile. Hopefully we won’t see any Gulags in our country. But Applebaum’s book serves as a warning.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

(1962, Audible 2013), 5 hours and 5 minutes.

This short novel is set in a Gulag during the early 1950s. The prisoner wakes in his bed and begins to plan his day (or how to get out of work). It’s cold but not cold enough for them to call off work. Soon, they are all awake and begin their morning routine. He wraps his feet for warmth and worries if he will be discovered with extra cloth. They are not to hoard, but everyone does. This morning, he visits the infirmary hoping to be sick enough to avoid work. With his temperature only slightly elevated, he must work. He eats breakfast, where he’s given bread for lunch. Does it eat it all or save it and hope it isn’t stolen before lunch? Then everyone assembles for the morning count before marching off to their various jobs. Denisovich is a mason. He finds where he has hidden his trowel. He has a favorite one and is supposed to turn in the tools at the end of a shift, but he doesn’t. Laying block with the weather being well below zero means they must melt snow and warm the sand and mortar. At least it requires a fire. They work through the day. In the late afternoon, they march back for an assembled count. Standing in the cold, he hopes everyone is present and there would be no need for a recount. Then there is dinner and bed.

The story is grim. I felt the cold, the hunger, and the foreboding existence within the Gulag. There, the prisoners are not called comrades. Inside the prison camp there are those who faithful to the Soviet Union and others, like Ukrainians, who are not. There’s the Baptist who hides his New Testament and who has a different hope. But most people exist without hope. The day ends, the light in the barrack goes out, and the reader is left to understand that the next day will be the same.

The novel takes place in the early 1950s at a time when Stalin was still alive. Interesting, Khrushchev as Premier, read a copy and allowed it to be published. At the time, he attempted to move the Soviet Union away from Stalinism. The book publication occurred just before the “Neo-Stalinists” booted Khrushchev and replaced him with Brezhnev.

I was amazed the way this book highlights the quotidian events in the life of a prisoner in the Gulag. The writing (or translation) is stark and amazing. I started listening to this book immediately after finishing Anne Applebaum’s Gulag. I highly recommend reading it and wish I had read it earlier. The book will go back on my TBR pile as it is as worthy of rereading as Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea.