To read about my journey from Edinburgh to Iona, click here. The trip involved two trains and two ferries!

Grasping the rail to hold steady, I stand on the starboard catwalk looking out across the waters. I pull up the hood on my rain jacket. I could go below, but I want to face the angry sea. The engines roar and black smoke puffs from the stack as the ferry pulls away from the Flonnphort’s dock. Moments later, we are in open water. The north wind whistles through the channel separating Mull from Iona. The pilot steers the boat into the wind, but the waves and tide push us southward. He increases speed as I spread my legs apart in order to remain upright. The boat rolls back and forth in the waves.

In a few minutes, we’re well out into the channel. The Abbey is clearly visible, standing tall in the shadow of Dun I, the high point on the island. We’re just the latest travelers, joining a hoard of pilgrims reaching back to the sixth century. I have no idea what the week will bring, but the roughness of the channel reminds me of the island’s isolation. The ferry pushes harder as we approach the landing. The pilot steers the boat up into the wind then lands on the ramp. There is no natural harbor in Iona. The pilot keeps the engines engaged, keeping the boat in position as the crew lowers the bow ramp. The two cars onboard are allowed to drive off first, then the two dozen or so of us passengers follow. The first off the boat get wet when a wave breaks and crashes over the ramp. The rest of us learn to time our departure, waiting till a lull to move out on the ramp and to quickly make our way to shore. We’re on Iona.

On Pentecost, 563, an Irish abbot named Columba and a group of twelve disciples landed on a pebble covered cove on the south end of Iona. They found on this small island what they were looking for and established a religious community. At this time, sea travel was easier than traveling overland on non-existent roads. The small island became a center of faith and learning that extended throughout the mainland of Britain and Ireland and surrounding islands. Some scholars believe the Book of Kells was originally produced here. Others think the large standing Celtic crosses, so common in Scotland and Ireland, were first carved on this island.

The religious community thrived on Iona for the next couple hundred years. People would travel by sea, making a pilgrimage to the island of the saint known as Columba. Scottish Kings sought out the island for burial. Legend has it that even MacBeth, of Shakespeare’s fame, is buried here.

Around the tenth century, hostile visitors from the north, the Vikings, arrived. With their art and wealth, churches and monasteries were attractive targets. After several raids and the deaths of scores of monks, Iona was abandoned as a center of learning. Most of the monks moved back to Ireland.

By the twelfth century, the Viking threat had faded. The Benedictine Order reestablished the monastery on Iona, building the current Abbey. They were joined by an Augustine nunnery, whose ruins are just south of the Abbey. These two continued to thrive till the Scottish Reformation in 1560. Afterwards, the site began to crumble. But pilgrims and visitors continued to come.

In 1829, Felix Mendelssohn visited and although the seas were rough and he suffered from sea sickness, he was inspired to compose the Hebridean Overture on the nearby island of Staffa. A “Who’s Who” of British authors also made the trip including John Keats, Robert Lewis Stevenson, naturalist Joseph Banks, Dr. Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Sir Walter Scott and William Wordsworth

After the abandonment of the monastery, the property came under the control of the Duke of Argyll. Over time, with the harsh wet climate of Iona, the trusses rotted and the roof caved in. In the 19th Century, George Douglas Campbell, the eighth Duke of Argyll, began restoring the Abbey. Although a devout member of the Church of Scotland (Presbyterian), he allowed a number of different denominations (Presbyterians, Scottish Episcopal and Roman Catholic) to use the site for worship. Before his death, he deeded the grounds to the Iona Trust which has responsibility today for maintaining the site. The site is open to all denominations. Since the 1930s, the site has been operated by the Iona Community which uses it to hold ecumenical worship and to train people to work with the poor around the world.

Those who wish to participate with the community today are expected to spend a minimum of a week on the island. Guests live as a part of the community, staying in dormitory rooms (six or eight people of the same sex per room). The guests help with the cooking and the cleaning, and participating in morning worship and evening prayers. The community strives to bring people together from all over the world as a way to foster a better understanding of one another. Groups meet together for Bible Study as well as to discuss other topics, with plenty of free time to explore the island or to take boat trips around the island or to other islands. Staffa, a small island with unique geology, known for puffins that nest there in the summer and “Fingal’s Cave” is a popular destination.

I spend my week on Iona meeting with a group led by two professors of British Universities. Both are poets. One teaches English while the other teaches in a seminary. As for my chores, I am in the kitchen, mostly chopping vegetables. Although the food is not exclusively vegetarian (we had meat three times during the week), we ate lots of wonderful vegetarian dishes that included roasted root vegetables and thick soups, all prepared from scratch.

With my spare time I hike around the island. Daily, generally around sunset (10:30 PM), I hike to the top of Dun I, the high point of the island. The sunsets are incredible. At night, I can see distant lighthouses. One of the lighthouses was built by Robert Lewis Stevenson’s father in the early nineteenth century to warn boaters of Torran Rocks. This is also the site Stevenson’s chose for the shipwreck in. his book, “Kidnapped.’ I also gaze out on other islands in both the Inner and Outer Hebrides chain. Twilight seems to go on forever and provides some of the most beautiful light on the island and sea.

Friday is my last day and I, along with many other pilgrims, are leaving on the 8:15 AM ferry. Its drizzling rain, but calmer than the day I’d arrived. The Iona staff gather at the dock to wish us a safe trip. Once the ferry lands in Fionnphort, there’s no time to waste. A bus waits. We load up and ride across the Ross of Mull and Glen More, to Craignure, where we meet another ferry. It’s nearly an hour over to the mainland, to Oban, where we board a waiting train.

Most of those whom I’d spent time with on Iona continue on to Glasgow and home. But not me. At Crainlarich, where the Oban branch merges onto the Northwest Highlands mainline, I say my goodbyes to friends and step off the train. Thirty minutes later, I board a northbound train, taking me through Fort Williams and over the Glenfinnan trestle (made famous in the Harry Potter movies), and on to Mallaig where I catch the ferry to the Isle of Skye.

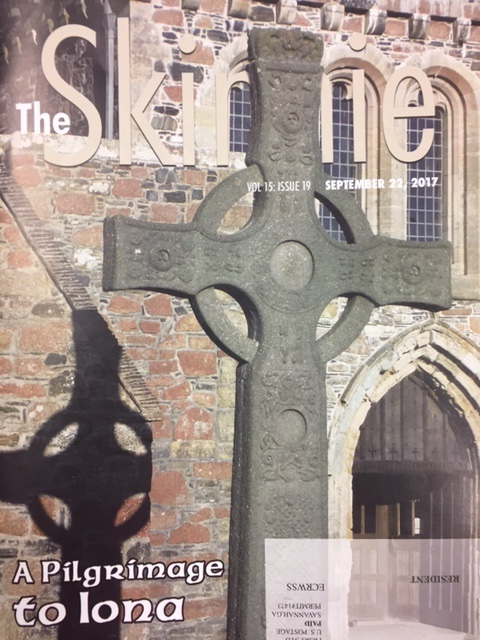

This story originally appeared in The Skinnie, a magazine for Skidaway Island, on September 22 , 2017.

Cl