In case you haven’t noticed, I’ve been away the past week. During this time, I did several things I’ll write about, the first being a project I’ve been associated with for the past few years. The next day, I attended a friend’s book reveal, and then spent a few days paddling out to and camping on Cape Lookout. I’ll write about the other two things later.

Between the 7th and 8th Grade

Excitement filled the air as the 1970-71 school year ended. I had just finished the 8th Grade at Roland Grice Junior High. In an art class, I had drawn with color pencils a large portrait of Yogi Bear and had friends to sign it. Next year, we’d rule as 9th graders. But things were changing in ways we did not realize. While we had no way of knowing at the time, this was our last day at Roland Grice.

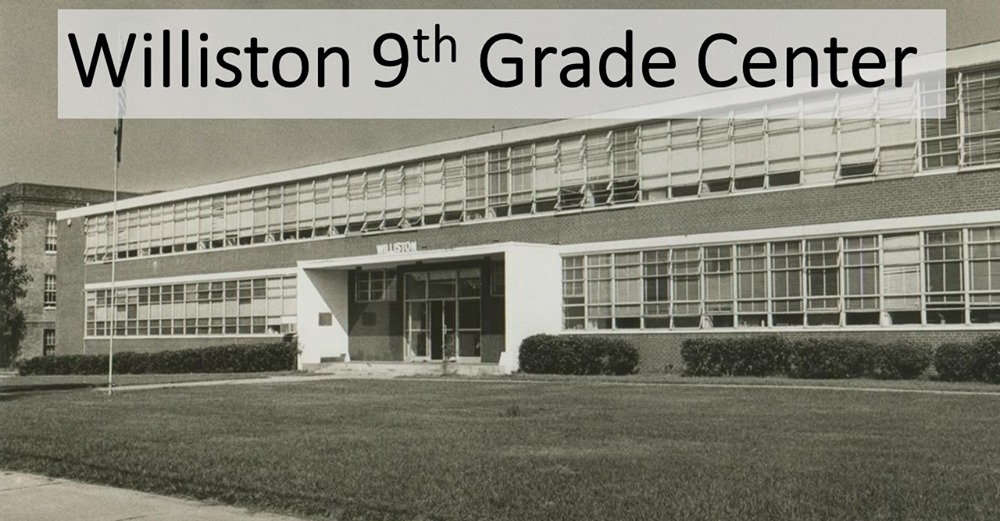

During our summer break, a court decision forced the complete integration of schools. Those students at Roland Grice who lived north of Oleander Drive would attend D. C. Virgo, which had been the former African American Junior High, which was one of the county’s two “9th Grade Centers.” Those of us who lived south of Oleander would attend Williston, the former black high school. Interestingly, D. C. Virgo was the principal at Williston that made it celebrated school during the time of segregation. In 1968, after the opening of Hoggard High School, Williston was converted to a Junior High. Now, it would be the county’s other 9th Grade Center. The goal was to have all schools to reflect the county’s racial make-up which, in 1971, was roughly 70% white and 30% African American.

9th Grade

It was late in the summer that we learned of the changes. That September, I took the bus to Roland Grice and from there transferred to another bus for the ride to Williston. This was a scary time. Since 1968 and the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., Wilmington had its share of riots and racial unrest. New private schools such as Cape Fear Academy and Wilmington Christian Academy popped up in response to the forced integration. However, most of us continued in public school.

The 1971-72 school year would be one of the most memorable years in my life, not because of what I learned in the classroom, but what I learned about life and people. We were a part of great experiment, which while it contained personal disappointments, was necessary for the well-being our society. Sadly, I didn’t get to finish out my year at Roland Grice, but greater good is that the unequal segregated system of schools needed to be undone. Those of us who attended Williston, at least those willing to open our eyes, saw first-hand how unfair the old system had been.

50th Anniversary Project

At a class reunion a few years ago, I found myself discussing our year at Williston with several students. As we were coming up on our 50th anniversary, it seemed that we should do something. As the first students to experience busing, at least for historical purposes, we should preserve some our memories and perhaps even take another step or two toward healing the racial divisions that have divided this country for too long.

Cliff, a classmate who was also the son of the school superintendent for the county in 1971-72, be talking. We reached out and talk to others, creating a group of students from across the racial spectrum. We started a Facebook page, which revealed how our experience, 50 years later, still contains extremes. There were those who thought the year was wonderful. One black woman recalled it was the first time in school she was given a new textbook. Before, her schools issued “hand-me-down” books from schools that was most white. And then there are the few who hated everything about Williston and still carry a grudge.

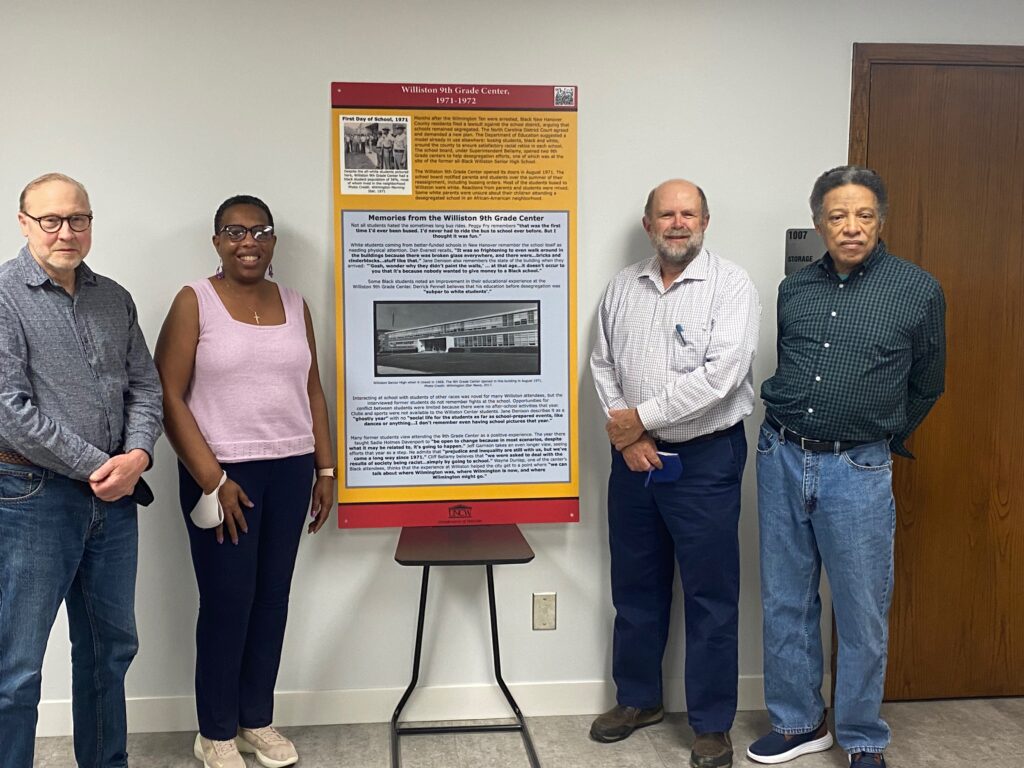

We searched for a way to memorialize our year at Williston. Thanks to another of our classmates, LuAnn, who had graduated with a master’s degree in public history from University of North Carolina at Wilmington, we were connected to this department. Three graduate students of the program began to collect oral histories and created a series of interpretive panels about the experience of integration in Wilmington.

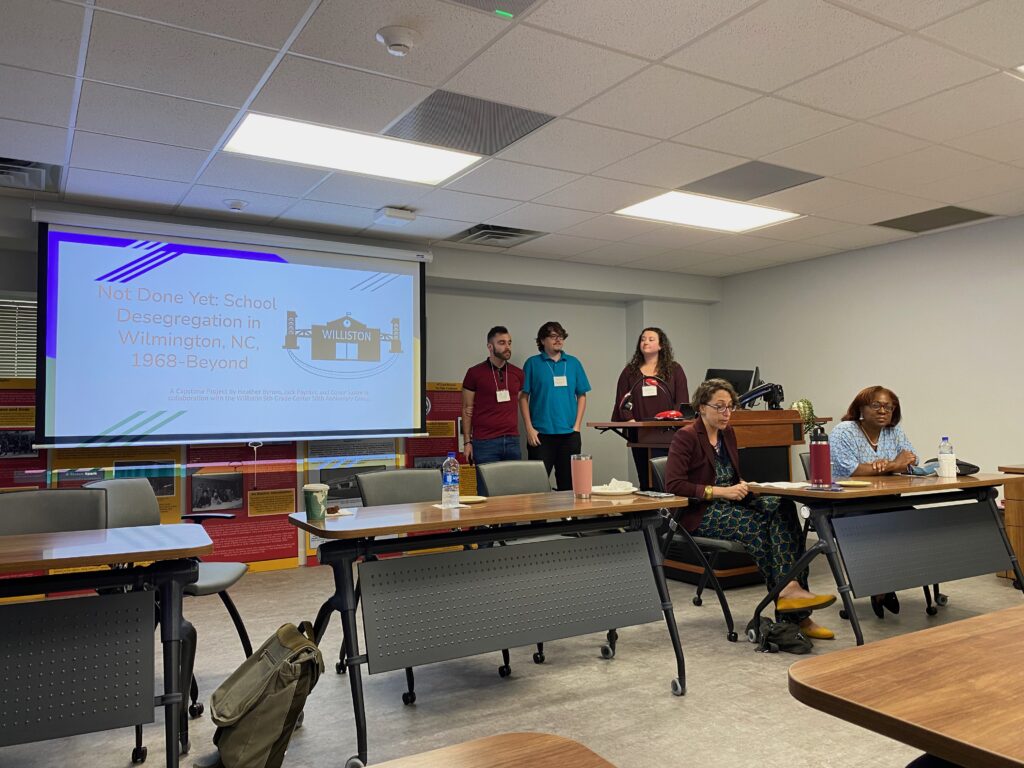

Last Friday, the UNCW students presented their work. The panels will be displayed at Williston, which today is a middle school. The oral histories will be available for future scholars through the UNCW library. At the presentation, I learned that busing was no longer being done in New Hanover County and that at present, Williston’s student population consists of 80% minority. I wondered if our sacrifices were in vain.

Faculty: Dr. Jennifer LeZotte. & Dr. Tara White)

The students titled their project, “Not Done Yet: School Integration in Wilmington, NC, 1968-Beyond.” Click on the link to learn more.

I am thankful for this project. Not only does it add to the historical body of material available on integration in America, it also allowed me to catch up with old friends and to make some new ones.