Jeff Garrison

Mayberry & Bluemont Churches

April 27, 2025

Revelation 1:1-8

At the beginning of Worship

In 1993, we took the train out west. I was invited to interview with the Pastor Nominating Committee for Community Presbyterian Church in Cedar City, Utah. We decided to make it a vacation. I took two weeks off, spending time exploring old mining towns like Pioche, Nevada along with Bryce Canyon, Zion Canyon, and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. While I didn’t know it at the time, I would spend the next decade living in that area.

After our trip was over, we got back on the train in Las Vegas.[1] Exhausted, Iwent to sleep soon afterwards. Around 4 AM, I noticed we weren’t moving. It was dark out and I couldn’t see much. I assumed we were on a siding waiting for a freight train to pass.

A little after 6 AM, I got up and went to the lounge car for coffee. We still hadn’t moved, and I was curious about what had happened. I asked the car attendant. He said we’d “died on the line.” I wasn’t familiar with this term and asked what it meant. It refers to the operating crew (the engineers and conductors) exceeding the hours they can legally work. When this happens, standing orders requires them to pull their train onto the first available siding and wait for a replacement crew. We were in remote area of the Black Rock Desert of Utah this morning. It took them 4 hours to get a crew to us.

Then, as this was a year of terrible flooding in the mid-west, they’d lowered the speed limit along much of the line because the ground was so soft. By then, we were running too late to make our connection in Chicago. The tempers of passengers ran little thin. Yet, the car attendances did everything they could to make the trip pleasant. When the dining car ran out of food (since they had two more meals to serve than planned), we stopped in some small town in Iowa. A van waited beside the tracks, filled with boxes of Kentucky Fried Chicken.

They assured us they’d be someone to help in Chicago with alternative transportation or hotels. On top of it all, they remained calm and pleasant at during a trying situation.

Those of us who make up the church need to be like those attendants on that train. We should maintain a positive outlook while we encourage one another and keep out eyes on Jesus. While it may not always appear this way, he has everything under control.

Before reading the scripture:

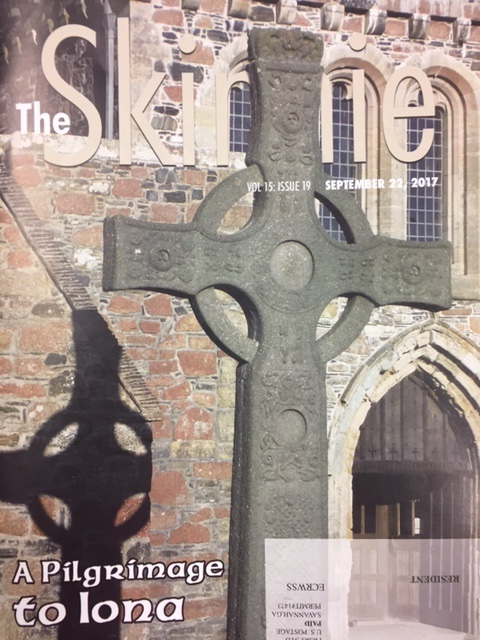

For the next couple of months, I’m going to be preaching on the first opening chapters of the book of Revelation. Remember, this book is singular. It’s not Revelations, but Revelation.

Sometimes even those who print the Bible call the book “The Revelation of John. That, too, is wrong.

The title of the books in the Bible were added much later. In the opening verse, we learn it’s the Revelation of Jesus Christ to his servant John.

This book is a letter to the seven churches of Asia. These churches are in what we know today as Western Turkey.

Read Revelation 1:1-8

As you may have gleamed from my opening story this morning, I love trains. There’s something about being on a train and watching the landscape change. People on trains are not as hurried as they are on airplanes.

I’ve mentioned before how trains can serve as a metaphor for the Christian journey. Many gospel songs express this. “Life is like a Mountain Railway” has the refrain: “Keep your hand upon the throttle and your eye upon the rail. Blessed Savior, thou wilt guide us…” Or the old African American spiritual sung by the likes of Woody Guthrie and Peter, Paul, and Mary, “This train is bound for glory.”

I’ve always thought the long-haul train as an example of our Chrisitan lives. In winter, they assemble trains filled with produce in Southern California. Three days later, the produce is served in restaurants in Chicago. A day later, it’s being sold and served on the east coast. It’s quite amazing. One engineer doesn’t take the train across the nation, over 3,000 miles. Instead, every 8 to 10 hours, a new crew takes over, so that by the time the train pulls into Chicago or New York, a dozen or more crews have been at the controls.

Christ’s Church operates in a similar way. Pastors come and go. So do elders. So do members. Sometimes the tracks are smooth, and the train makes good time. Other times, curves and hills, mudslides and washed-out ballast, slows the train down. Likewise, with the church, there are times things go well, and other times we struggle.

When it’s our time to take over the throttle, we must ask ourselves, “Are we being faithful to Jesus Christ?” “Are we doing our best to safely move the train a little further down the track, knowing that we’re a part of something much larger than ourselves? As the church, we’re a part of something eternal, as we see in our morning reading from the Revelation of Jesus Christ.

The letter proper begins in verse 4, with two words: grace and peace, words I often use at the beginning of worship. The order is important. Grace, which comes from God, is always first and a prerequisite for peace. Without God’s grace, we’d be lost.[2]Without grace, there can be no peace.

John indicated three sources for this grace and peace. First, it comes from the “Lord God, who is and who was and who is to come, the Almighty.” This paraphrases God in Exodus, who revealed himself to Moses as the great “I am who I am.”[3] God is revealed as the eternal one, the one beyond our comprehension. God is creator and present throughout history. The second source comes from the seven spirits. There’s some debate over the meaning of this, but I think there is much merit in the ancient believe that this is a reference to the Holy Spirit. Throughout the Book of Revelation, seven is considered the number of perfection and the seven spirits imply the Spirit’s fulness.[4] The third source of this greeting is from Jesus Christ.

The three sources of greetings, from God the Father, the Holy Spirit, and Jesus Christ the son provide us with a Trinitarian view of the Godhead. It’s a little strange to have the Spirit ahead of the Son (we usually think of Father, Son, and Spirit[5]), but this construct allows john to slip seamlessly into detail about Jesus Christ, God’s revelation to us.

John tells us Jesus Christ is God’s faithful witness. He reveals God to us and by knowing him, we can know God the Father.[6] Remember, this book was written to churches soon experience persecution. Many believers would die. Many more would die over the next two thousand years for their faith as we saw this month with over 240 deaths of Christians in Nigeria.[7]

Jesus is designated as “firstborn of the dead.” This title encourages those about to face martyrdom, reminding them (and us) that life on earth is temporary. We have eternity to which to look forward. Furthermore, Jesus is the ruler of the kings of the earth. We may live in fear of earthly kings. But we should never forget that one day everyone will be called to account. And just because one has the power of a king on earth and can seemingly do what he or she wants doesn’t mean they’ll not be held accountable for their actions.

John’s description of our Lord continues at a personal level as he reminds his readers (and us) what Jesus has done. “We’re loved, we’re freed from our sin, and we’ve been brought into a kingdom, a family, where we’re established as priests who serve God forever. One of our most important Protestant doctrines is the “Priesthood of All Believers.”[8] As priests, all glory should flow from us to the eternal God.

In verses seven, John refers to Jesus’ return. Going back to his reminder that Jesus is the “King of kings,” we’re further reminded that upon his return everyone (including those who killed him) will see Jesus. Of course, for some, this will cause a great deal of concern and there will be wailing and weeping from those who nailed Jesus to the cross or harmed his followers.

As I said earlier, Revelation is written as a letter and today, we’re looking at the salutation section. This ends at verse eight, which reflects on what we’ve already heard in verse 4. Jesus is eternal, co-eternal with the Father.[9] I am the Alpha and the Omega (the A and the Z we might translate it). Jesus is Almighty, who was, who is, and who is to come. Later, in Revelation, we’ll see other titles for Jesus, such as the lamb slain who rules in glory.[10]

Jesus’ sacrifice leads to his glory. And if we follow Jesus, we should not worry about the cost. The benefits will outweigh the costs and the suffering we might endure. In the end, God through Jesus Christ will be victorious and those who follow Jesus will share in the victory. That’s the message of the Revelation. Amen.

[1] At this time, there are no trains through Las Vegas. But in the 1990s, the “Desert Wind” ran from Los Angeles, through Las Vegas, and joined the California Zephyr in Salt Lake City.

[2] Bruce M. Metzger, Breaking the Code: Understanding the Book of Revelation (Nashville, Abingdon, 1993), 23.

[3] Exodus 3:14-15.

[4] See Metzger, 23-24. The idea of this being the Holy Spirit was made in a 6th century commentary on Revelation by Andrew of Caesarea, Commentary on the Apocalypse, 1.4. For alternative interpretations of the seven spirits, see Robert H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation, revised (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1997), 46-47.

[5] See Matthew 28:19.

[6] John 14:7.

[7] https://www.christianitydaily.com/news/nigerias-christians-suffer-losses-in-april-death-surpasses-240.html

[8] See “The Second Helvetic Confession,” Presbyterian Church USA, Book of Confession, 5.154.

[9] Westminster Confession of Faith, VII.1, and The Nicene Creed.

[10] Revelation 5:12-13. The word “Lamb” appears 29 times in Revelation.