This is the second story in my bakery saga. Unlike the first story about Linda, which I wrote years earlier and revised, this is a new story. While the bakery was always hot, this post isn’t nearly as steamy as the first one. It also has more technical detail that’s required to fully understand what I’m talking about.

Summer’s End

As the summer of 1976 wrapped up, I called into the plant manager’s office. That morning I’d given my two-week notice. My plan was to leave the bakery as I returned to college. I would also work in the fall part-time at a Wilson’s Supermarket on Oleander Drive, where I had worked for several years. Even during this summer at the bakery, I still put in six or eight hours a week there, mainly ordering and tending the cigarette aisle. It’d been a busy summer, and I had no idea why the plant manager wanted to see me.

“I’d like you continue working here,” he said. “In a few months, I think you’ll be a supervisor. And I promise to keep you on second shift, if you can arrange your schedule to take morning classes.”

He also noted that for the time being, I would be the second shift operator for the bread slicers and baggers. I had already spent some time that summer learning and running this equipment due to an accident earlier in the summer.

Roy’s accident with the wrapping machine

One hot day, a major breakdown occurred in the proof box. This meant we didn’t have bread to package for several hours. After cleaning up our workstations, there was little for us to do until they got the operation back running,. We hid out on the loading deck. Roy was the second shift operator for the slicers and wrappers. He proceeded to smoke a couple of joints. By the time the bread production resumed, he was feeling pretty good. But his thinking wasn’t very clear, nor his reflexes fast.

In other that your thinking will be clearer, let me explain the process. As a loaf of bread approached the bagger, a shot of compressed air blew up a bag. This signaled an arm to shoot, out, catching the loaf of bread and sliding into the bag. As the arm retreated, the bread was inside the bag and dropped onto another conveyor. It then moved through a machine that sealed the open end of the bag with a twist tie. The arm that caught to bag was sharp and shiny, made of stainless steel. This was so it could easily slide into and out of the bag. If the bag didn’t open, there was a switch that would stop the machine. There was also a metal lattice grate that protected the operator from the arm. If the grate wasn’t fully extended, there was another switch that kept the machine from operating.

On this day, the wrapping machines were having problems. This often happened on really hot days as the bag would stick, or when the bags were old. Roy was constantly having remove stuck bags. To expedite things, he tapped down the switch that kept the machine from operating when one’s hands were inside the grate. Then, when cleaning up some bad bags that had jammed the machine, he accidently tripped the switch that indicated the bag had blown open. The metal arm shot out to catch the loaf and sliced into the flesh on Roy’s forearm. Blood went everywhere. He required 20 or so stitches.

That evening, Paul, the supervisor began teaching me how to operate the machinery. The next day, instead of traying off bread, I ran the machines. They kept Bobby, the first shift operator over to help train me and until we had no more change overs. I worked for a few days as an operator, but then went back to bagging when Roy returned.

Roy would only work another week or so before he quit. I never completely understood him. He had left the army after 10 years, which he had worked primarily as a cook. He learned the baking trade in Vietnam, where he worked in an American built field bakery supplying troops in the country. I never knew why he left the bakery and I never saw him again. From this point on, I was operating the equipment, even though I was still making the wage of a bread trayer. But my summer was almost over and It was a week or so later I was in the plant managers office.

Two job offers

I asked time to think about the offer. The grocery store I was working for had also offered me a similar position. They were opening a new store near Monkey Junction. Bert, the manager who had hired me, was being moved to the new store and offered me to come along as the “third man,” essentially the second manager, who main job would be to close the store several nights during the week. It was tempting, but in the end decided I would stick to the bakery. Having worked in the grocery store through high school, I’d done most of the jobs throughout the store except for in the meat department. The bakery was still a mystery, so I accepted the offer. When classed resumed, I left the grocery store and began to work fulltime on second shift at the bakery.

Operating the slicers and baggers

About a month later, the plant manager left. I was never sure if he quit on his own or if he was fired, but I would not be a supervisor for nearly three more years (and two plant managers later).

While I was not a supervisor, I was the lead on a four-person operation. This was especially true after some remodeling of the plant. When I was hired, the bread traying operation occurred in the shipping area (and faced Linda’s work station). There, two conveyors from the wrapping machines brought the bread through a wall. This was the position was just behind the roll wrapping area, providing me with Linda. At the end of the summer, they cut out the wall and moved the bread trayers next to the wrapping machines. This allowed for the wrapping operator to be able to interact more easily with the trayers.

The process

The bread came into the wrapping area from the cooler, where it had spent approximately an hour cooling to where the outside was crusty, but the inside was still warm. This was necessary for the bread not to mash up in the slicers. This bread came out on a single conveyor, which split into two before going through the slicers. A woman generally worked at this position, making sure the operations ran smoothly. Whenever one of the machines were down, she would take off the excess bread and place it on waiting trays. Then, she would feed it back in when things ran well.

The slicers were large bandsaws, but instead of a single blade, there were sixteen or so blades. Each blade was circular and five feet or so in diameter. Inside the machine, the blades twisted in a figure eight around two drums. This allowed the cutting surface of each blade to face the incoming bread and resulted in two slices per blade. A few extra blades were stored on the drums of each slicer. This allowed for the operator or a mechanic to quickly move blades over to replace a broken one. The razor sharp blades were dangerous. The equipment remained closed, except for where the bread entered and departed. If one of the doors on the machine opened, a switch shut the saw down down. A broken blade flying free would be deadly.

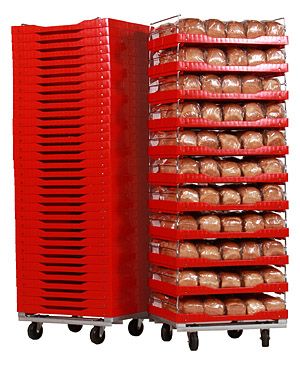

From the slicers, the bread traveled by a conveyor, maybe ten feet long, to the bagger. This conveyor had sides that were set to the bread to keep the slices from falling. After bagging and tying the loaves, they were placed on to trays and racks, which the shipping department then handled. In some ways, this was an easy job, when things went well. This was especially true after all the changes that came with morning variety bread. Once we started with the pound and a half white bread, which was so popular back in the 70s, we only changed the bags. During the summer busy season, we’d often bag 60 or 70 thousand loaves of white pound and a half bread at a rate of 4200 loaves and hour.

I became friends with Bobby, who was the morning operator. He’d often punch out and then come back over and talk. On a few occasions, on our days off, we went out rabbit and squirrel hunting. He had several uncles and cousins with beagles who lived on farms just inside Pender County. At the time I didn’t think about it, but I now wonder what some people would have thought to see a white guy running around several African Americans, all of us armed with shotguns or rifles.

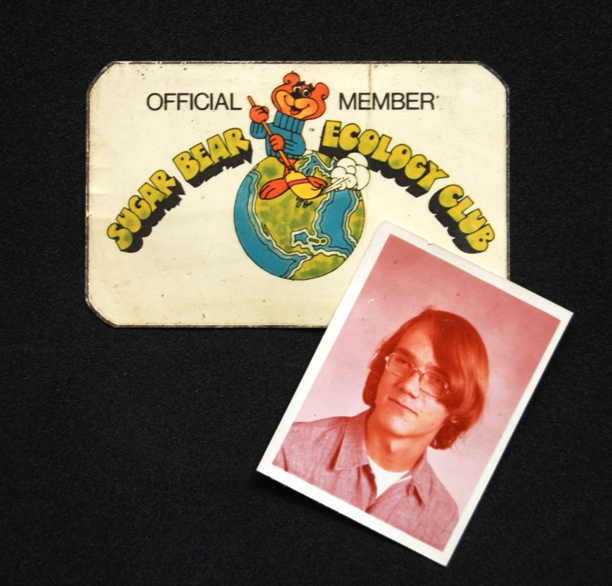

While everyone in management remained silent about me becoming a supervisor, I was honored during this time as the company’s outstanding employee for the first quarter of 1977-78. In addition to a nice plaque, the management treated outstanding employees and spouses to wonderful dinner at the Hilton on the Cape Fear River. (Looks like I should clean up my plaque!).

My minor injury

I did have one injury while running the bakery machines. As a promotion, we were placing game cards inside each of the loaves of bread. This required a separate machine to sat next to the conveyor between the slicer and bagger. It was always creating problems when the placement of the card wasn’t perfect. At one point, a card was near the bag opening, which jammed up the tying machine. In trying to free the bags, I pulled out a pocketknife. Leaning over the equipment, I supported my weight on my left hand as I cut out the bag and card with my right hand. When the knife slipped, and the blade went into my left hand, requiring a couple of stitches. The scar is still visible.

My learning from this event happened in the emergency room. I joked that I’d been stabbed. They followed their procedure and called the police. I attempted to clarify. It was truthful, I had stabbed myself. But it was an accident. The hospital visit would be filed on a workers compensation claim. And, to make me look innocent, I wore a white bakery uniform sprinkled with bits of crust from the bread.

Oven operator

After about a year as an operator of the wrapping and bagging machinery, I was asked if I would like to move over to the bread oven. This was a solo job, but it came with another pay raise and a lot more responsibility. Mainly I oversaw the operations of about a 1/3 of the production area. One main task involved continually monitoring the temperature in the oven and the humidity in the proofer. This was in addition to making sure everything ran smoothly. The size to the equipment in my area was similar to a house. Since there were three major pieces of equipment, my work area represented the size of a small neighborhood.

Oven operations

The bread came back to my area on a long conveyor from the make-up room. There, the dough was placed into strapped together pans that held four loaves. The bread first entered a proof box. The temperature in the box was kept around 110 degrees with nearly 100% humidity. Automatic arms pushed the bread pans, ten four loaves pans at a time) onto racks. Windows into the proofer provided a glimpse at how the bread was rising. When the dough rose to the top of the pan, another arm pushed the pans onto a conveyor. From there, the bread travelled to the oven.

Between the proofer and the oven, a machine placed lids onto the bread if we were making square top loaves. The operator had to place the lids onto the conveyors at the beginning. That was easy as the lids were cool. After that, the lids recycled until the end of the day. As second shift ended the workday, I had to pull off the lids. These were hot and more than a few times I burned my forearms.

The oven worked liked the proof box with arms pushing and pulling the pans onto and off of racks. The oven consisted of seventy-some burners, which needed to occasionally be checked. Sometimes burners had to be scraped out to get them to relight. In addition there were 6 temperature zones. If the bread wasn’t tall enough, I’d reduce the temperature in the first zone to allow it to rise a bit more. If it was too tall, I could increase the heat to kill the yeast faster. Each zone had gauges that checked continually.

Leaving the oven, the pans went through a machine that first removed the lids (if used). Then, by suction cups, the loaves were lifted from the pan and placed on a conveyor for the cooler. The loaves would remain in the cooler until it was time for them to go to the slicers. The entire process, from arriving at the proof box till leaving the proofer, took approximately 2 1/2 hours.

The pleasure and perils of being an oven operator

I had the horn if case there was a problem. It could be heard throughout the plant. If I blew it, the supervisor and the mechanics on duty immediately ran to my aid. Even a break down of a few minutes could cause us to lose upwards of 6000 loaves of bread. In later stories, I’ll share some horror stories.

But running smoothly, I was left alone with my thoughts, as I continually checked on things. When taking classes at the university in which I had to memorize lots of stuff, I would keep index cards in my pocket. Then I would run the cards occasionally throughout my shift.

I would continue working as the oven operator until my last semester in college, which was when I was moved into supervision. While it seemed long, I had just turned 22 years old. I had been at the bakery less than three years.