Merry Christmas everyone. Today was beautiful in South Georgia, a nice day for a walk with the dog, after opening present, playing a new board game (Ticket to Ride: Rails and Sails), and continually snacking on ham. For the past few days, we’ve experienced a deluge (6 inches of so of rain). But yesterday afternoon, the clouds dispersed in times for us to line the church driveway with luminaries for our evening service. Our sanctuary is most beautiful when decorated and filled with candles. Unfortunately, I’ve been fighting a head cold for the past week, but thankfully I was on an uptick yesterday, which made the evening much more pleasant. I will work tomorrow and then be on vacation for the rest of the year. But I do have a few more post. Below is my message for the candlelight service last night.

Christmas Eve Meditation 2019

Jeff Garrison

Bethlehem wasn’t a thriving town. It wasn’t the capital. It was off the beaten path. It’d seen its better years as Jerusalem grew and became the place to be. When you entered the city limits, there might have been a commentative sign acknowledging their favorite son, David, who went on to be the King of Israel. But I bet there were some who still harbored ill feelings toward David. He was the one who put Jerusalem on the map, positioning the Ark of the Covenant on the spot where Solomon would build the temple. Since those two, David and Solomon, almost a 1000 years earlier, Jerusalem prospered while Bethlehem slipped into a second-rate town.

Bethlehem was the type of town easily by-passed or driven through without taking a second glace. It might have had a blinking stoplight, or maybe not, like the towns we drive through when we get off the interstate.

Bethlehem could have been a setting for an Edward Hopper painting. He’s mostly known for “Nighthawks” a painting of an empty town at night with just a handful of lonely people hanging out in a diner. It’s often been parodied in art, with folks like James Dean and Marilyn Monroe sitting at counter. But all his paintings are sparsely populated, providing a sense that time has passed his urban landscapes by. Or maybe the town could be a setting for a Tom Wait’s song—the roughness of his voice describing lonely and rejected people, struggling through life.

In many ways, Luke sets up Bethlehem by placing the birth of the Prince of Peace in a historical context. In Rome, we have Augustus, the son of Julius Caesar. Some twenty-five years earlier, he had defeated all his enemies and the entire empire is now at peace. The glory of Rome far outshines even Jerusalem and makes Bethlehem seem like a dot on a map. Caesar has the power that can be felt in a place like Bethlehem, but he probably never even heard of the hamlet. And, of course, the peace Rome provides is conditional. This peace is maintained at the sharp points of its Legion’s spears and swords and, for those who would like to challenge the forced peace, the threat of crucifixion. Luke also tells us Quirinus is the governor of Syria.

Those rulers are in high places. They dress in fancy robes, eat at elaborate banquets, and live in lavished palaces. They aren’t bothered by the inconvenience their decrees place on folks like Mary and Joseph. This couple is one of a million peons caught up in the clog of the empire’s machinery. If the empire says, jump, they ask how high. If the empire says go to their ancestral city, they pack their bags. It’s easy and a lot safer to blindly follow directions than to challenge the system. So, Mary and Joseph, along with others, pack their bags and head out into a world with no McDonalds and Holiday Inns at interchanges. For Mary and Joseph, they head south, toward Bethlehem.

If there were anyone with even less joy than those who lived or stayed in Bethlehem, and those who are making their way to the home of their ancestors, ancestors who may not have lived there for generations, it would be the shepherds. The sheepherders are near the bottom of the economic ladder. They spend their time, especially at night, with their flocks out grazing. The sheep are all they have. They have to protect them. They can’t risk a wolf or lion eating one of their lambs. So, they camp out with the sheep, with a staff and rocks at hand to ward off any intruder. They don’t even like going to town because people look down on them and complain that they smell.

You can’t get much more isolated than this—a couple who can’t find proper lodging in Bethlehem, with the wife that’s pregnant, and some shepherds watching their flocks at night. But their hopelessness quickly changes as Mary gives birth and places her baby in a manger. There is something about a baby, a newborn, which delights us all. Perhaps it’s the hope that a child represents. Or the child serves as an acknowledgement that we, as a specie, will live on. While birth is a special time for parents and grandparents, an infant child has a way to melt the hearts of strangers who smile and make funny faces and feel blessed if the mother allows them to hold the child for just a moment.

This child that comes into this town and brings joy. Joy comes not just to the parents, but also to the angels. The angels share the joy with the shepherds. The shepherds want in on the act, so they leave their flocks and seek out the child. All heaven is singing and sharing the song with a handful of folks on earth. The shepherds also are let on the secret that, so far, only Mary and Elizabeth and their families share. This child, who is to be named Jesus, which is the same word that in the Old Testament is translated as Joshua, is coming to save the world. Soon, in a few generations, the song will spread around the known world.

And for this night, the sleepy hamlet of Bethlehem is filled with joy. The darkness cannot hide the joy in the hearts of this young mother and father and the shepherds. Something has changed. Yes, a child has been born. But more importantly, this child is the incarnation. God has come in the flesh, in a way that we can understand. God has come in a way to reach all people, from the lowly shepherds, to the oppressed people on the edge of the empire, to all the world. This child, whose birth we celebrate, has brought joy to the world.

Friends, as we light candles and recall that night in song, may you be filled with the joy of hope that comes from placing our trust in Jesus. Amen.

©2019

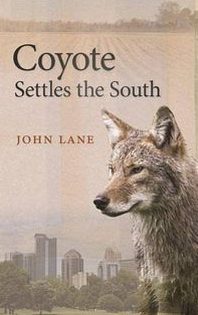

John Lane

John Lane

Bonnie Jo Campbell, Once Upon a River (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 348 pages.

Bonnie Jo Campbell, Once Upon a River (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 348 pages. Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (New York: Knopf, 1978), 720 pages including notes and index. Some plates of photos and artwork.

Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (New York: Knopf, 1978), 720 pages including notes and index. Some plates of photos and artwork. Edward Dolnick, A Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society and the Birth of the Modern World, 2012 (Audible 10 hours and 4 minutes).

Edward Dolnick, A Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society and the Birth of the Modern World, 2012 (Audible 10 hours and 4 minutes). John H. Leith, Assembly at Westminster: Reformed Theology in the Making (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1973), 127 pages.

John H. Leith, Assembly at Westminster: Reformed Theology in the Making (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1973), 127 pages. Not Guilty by

Not Guilty by