I will first share a story from the spring of my junior year of high school, followed by a review of a new religious biography of Richard Nixon. This is my last planned post till October 6. I am on vacation and will be away some from the computer. From the looks of the weather, I picked a heck of a time to take a week off!,

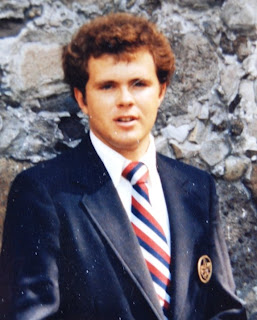

John T. Hoggard High School, Spring 1974

It all came to a head in Coach Fisher’s economics class. I took my seat in the class and when he saw me, he fumed.

“You are not allowed in my class,” he yelled, staring at me.

“I’m not leaving,” I said.

“Yes, you are,” he said, pushing desks with students sitting in them out of the way to get to me.

Scared, I stayed in my seat, thinking that if he physically harmed me, which he could easily do, I’d have a class of witnesses for an ensuing lawsuit.

Standing over my desk, he ordered me out into the hallway. I had spent the past two weeks sitting in the hallway, working chess puzzles in a magazine. This started when I challenged one of his diatribes about Richard Nixon. Nixon was in the news a lot in the spring of 1974.

The day before, at the end of the class, Coach Fisher told me I would fail his class because I had missed so much of it. I told him that I better not, because he was the reason I was missing his class. The class really had nothing to do with economics. Most of the 50 minutes was spent discussing basketball and other sports. What little had to do with economics was more about consumer spending than the relationship between price and demand or an understanding of macroeconomics. Fisher was a coach, who had been given a teaching position.

I decided it was time to end my exclusion from class, so the next morning, I returned.

After a few moments of a standoff, I told Coach Fisher that if he wanted me out of the class, we could go together to Mr. Saus’ (the principal) office. His anger grew and he started to drag my chair outside.

“Fine,” I said. “I will go to the principal’s office,” I said, getting up. He ordered me to sit in the chair outside his door, but I walked down the hall and turned toward the office. I expected him to follow, but he didn’t. Mr. Saus wasn’t available, but I was sent into Mr. McLaurin’s office. He was an assistant principal. I told him my story. He listened and had me remain in his office while he disappeared for a few minutes. When he came back in, he told me to go back to class, that Mr. Fisher would let me back in.

Fisher didn’t fail me for that six-week period. I passed the class with a decent grade without having to do anything because Fisher essentially ignored me for the rest of the semester. I just sat there. I would have to wait till college to grasp economics.

Richard Nixon was president during the formative years of my life. I was in the sixth grade when he was elected president in 1968. At the time, Nixon, to me, seemed to be the best choice.

I would continue to support Nixon throughout my junior high and early high school years. Why, I’m not sure. Why did I believed him when he said he didn’t do anything wrong? This belief was strong enough to encourage me to speak up for Nixon in Coach Fisher’s class, which led to our encounter. Later, after he resigned from the Presidency the summer after the above incident, I felt embarrassed. Some of that shame remains. How could I have been so naïve?

There were two events that happened in high school which my mom always blamed on me losing all respect for authority. And they happened about the same time. The first was a wreck. A young woman (she was 21) turned in front of me from the left-hand lane on Shipyard Boulevard. I hit her in the front quarter panel and both cars were totaled. Thankfully, my mom was seated right next to me and saw it all. I was knocked out and sent in an ambulance to the hospital. The young city police officer, whom my mother witnessed flirting with the other driver after the accident, charged me with following to close. From the damage to her car, that was an impossibility. Thankfully, a neighbor who was a state highway patrolman, came to our aid and helped prove my innocence. Click here for a sermon where I share more about the wreck.

I don’t think my mother even knew about the incident in Coach Fisher’s class.

The accident in which I was wrongfully charged occurred within a year of Nixon’s resignation. Mom was right. Both probably contributed to my cynicism when dealing with authority figures. And Coach Fisher became the icing on that cake.

Daniel Silliman, One Lost Soul: Richard Nixon’s Search for Salvation

(Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2024), 317 pages including an index, bibliography and notes on sources.

One Lost Soul is a religious biography of our 37th President. Silliman begins with a brief overview of Nixon’s early life, after which he jumps from one critical injunction to another to show the role religion played in Nixon’s political career. These include Nixon’s anti-communism work as a young congressman, the run with Eisenhower as Vice President and his “Checkers Prayer,” the role of religion in the 1960 election, his holding “church” in the White House, the Vietnam War, his outreach to China, the Watergate Coverup, his resignation as President, and a bit about Nixon’s life after his presidency.

Silliman’s theme is that Nixon spent his life, from childhood, with a desire to find acceptance and love. Such desire began in his father’s grocery story but continued throughout his life. His obsession led him to work hard. He believed in the “great man” theory of history and wanted to be such a man, as seen in his reaching out to China. He had a hard time accepting God’s love or the love others. On the night before his resignation, Henry Kissinger, the Secretary of State visited with him. On Nixon’s suggestion, the two men got on their knees and prayed. Nixon cried as he asked, “What have I done?”

Kissinger shared this moment with his staff members before Nixon called him to ask that he not tell anyone that he had cried. Kissinger later asked, “Can you imagine what this man would have been had somebody loved him?”

I had always wondered about Nixon’s background as a Quaker. I still remember a Mad Magazine from the time with a cartoon-like article about religion. When they got to the section on Quakers, one panel said something like, “There are 100,000 Quakers in the United States. The next panel said that Quakers don’t believe in war. The third panel featured Nixon saying that he was a Quaker. The final panel read, “That makes 99,999.

Silliman points out that California Quakerism differed from the East Coast variety in several manners. In some ways, it was more like a Methodist tradition, with focus on working out one salvation. Nixon saw military activity as a way toward peace, so instead of seeking a consciousness objector status during World War 2, he joined the navy. Even during Vietnam, Nixon maintained hope the bombings would bring the North to the negotiation table. While this upset many Quakers, the decentralized structure of the denomination meant that any church disciplinary actions would have to be taken by his home church in California. While Nixon continued to claim to be a Quaker, he had not been active in the church since a child.

As President, Nixon created White House worship services. For these, he would import ministers to preach. Interestingly, Nixon maintain total control of the service down to the hymns. The services served a political purpose as Nixon often invited those to attend as favors. These services were Protestant, but on one occasion was led by a Jewish rabbi.

Nixon could also be impulsive. In the middle of the night during the anti-war protests, he takes his valet (and some secret service agents) to the Lincoln Memorial. There, he talks to anti-war protestors who are camping out on the steps. He asks questions of them. When they depart, he expresses his hope their opposition to the war won’t turn into hate for the country.

Silliman points out many good things Nixon did. Certainly, his work with China stands at the top. But he also refused to play the religious card against John Kennedy in the 1960 election. While it would have probably worked at the time, he didn’t feel it appropriate. He was also deeply concerned with Civil Rights, even though for political reasons, he refused to make a public statement on Martin Luther King’s arrest during the 1960 election. In 1968, he tried to play it both ways, reaching out to Strong Thurmond and other who supported segregation. This was the beginning of the Republican “southern strategy.”

While this is a sad and tragic story, I can’t help but to have hope that at least Nixon had a conscious that bothered him. I didn’t come away from this book thinking he was a psychopath. There were times he had empathy for others and instead of thinking too highly of himself, he doubted his own self-worth. In a way, it was his lack of self-worth that made him so desperate to win and to prove himself.

This is a good book not just for understanding Nixon, but also understanding the difficult many people have in accepting grace.

This biography is a part of the “Library of Religious Biography” series. I have read several others in the series including Aimee Semple McPerson: Everybody’s Sister, Billy Sunday and the Redemption of Urban America, and Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Spiritual Life.