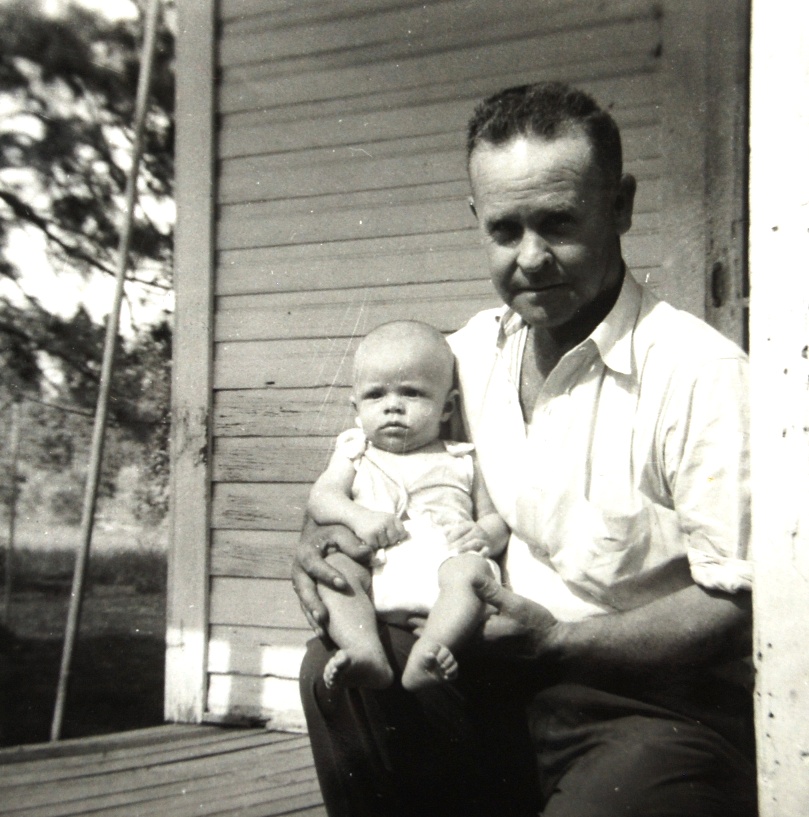

Granddaddy Faircloth

Christmas Day, 1966

Jeff Garrison

I’m now ten years older than you were

when I snapped that photo,

a nine year old boy on Christmas morning

with his new camera, a Kodak Instamatic.

It took some persuasion for you to get up

and step outside, but my grandmother coaxed

and with the camera you’d given me

I snapped a slightly crooked shot.

Mom said it was probably the last photo taken of you,

in a dress shirt beside your tall skinny bride, adorn in a white dress,

the two of you standing like sentinels by the holly bush

just off the front stoop where, in summer, we grandkids killed flies.

That photo has been lost for half a century,

but it’s still etched in my mind

your grin and crew cut hair,

and your arm around your wife, my grandma.

I wonder what you were thinking?

Did you want to get back inside to take a drag off your Lucky Strike?

Or sip dark black coffee from your stained cup?

Or ponder when we youn-ins (that rhymed with onions) would be quiet?

Perhaps, though, more was on your mind

as you thought how, in another month, you’d be preparing beds

in order to set out tobacco seed,

but that would be weeks after you took your last breath.

There’s much about you I’m curious to know,

things that’s been lost over the years.

When you visited us that fall of ‘66,

shortly after we moved to Wilmington,

you joked that we now needed a maid since we had a brick house

with two bathrooms.

Later that afternoon, we walked in the woods out back,

and you told of hunting among those pines during the war

when you were a welder at the shipyard,

and how they cut the bottom of your shirt off for missing a deer

Did you ever shoot a deer with that old Savage Stevens,

or did I avenge your bad luck,

when, as a seventeen year old, I downed a six pointer in Holly Shelter Swamp,

the only deer I ever had in that double-barrel (or any barrel’s) sights?

And I like to have an opportunity to see you once more

work in a tobacco field with your mule, Hoe-handle, pulling the plow,

or perched up on top of that orange Allis-Chambers tractor,

pulling a sled of Bright Leaf up to the barn for curing.

But what I’d really like to experience is a night with you at the barn,

keeping the fires hot by feeding wood into the heaters

under a sky filled with stars and lightning bugs

and the flickering kerosene lantern that now sits on my mantel.

On those evening, swapping stories with friends,

did your mouth water for something to quench your thirst,

something smooth that you’d long sworn off,

but the desire, I expect, was still there?

It must have taken quite a bit of strength,

to give up the drink and break with some of your brothers

as you strove to live a straight life

and earn the respect of your mother-in-law.

But I will never know, in this realm at least, any of this

and must be content of my memories of that Christmas,

in the home that belonged to the women around you,

your mother-in-law, your wife and your daughters.

You’d cut a beautiful red cedar that year,

decorated it with white lights, red bulbs,

and an abundance of icicles with presents for your grandkids

filling the floor around the base of the tree.

After our presents were opened,

you called us back to your bedroom where,

with boxes of fruits and nuts you stuffed bags for everyone,

contents that’ll have to last a lifetime.

John Lane

John Lane

For Hazel Brown

For Hazel Brown