Jeff Garrison

Mayberry and Bluemont Presbyterian Church

August 20, 2023

2 Corinthians 5:11-21

At the beginning of worship:

A dozen years ago, John Ortberg published a book titled the me I want to be: becoming God’s best version of you”[1] The title turned me off. It sounded as if went against my theology of focusing more on God and not ourselves. But I read the book. While a catchy title, the book goes deeper than I had expected and has some good insights.

God created a diverse world. We’re all different. Looks, shapes, the hue of our skin and hair, our abilities. We’re all unique. The goal of the church shouldn’t be to create a cookie-cutter version of a Christian. If that was even possible, we would create a boring organization. And we wouldn’t be effective! God calls us for a purpose. If we all looked, talked, and acted the same, if we all liked the same things, we would alienate ourselves from the rest of the world.

But that’s not what God’s wants. God created us as irreplaceable individuals. Consider Jesus’ original disciples. They were all unique: you had fishermen and tax collectors, a physician and a revolutionary, devoted followers and skeptics. We’re all unique and beautiful. We’ve been created by the Master Artist who designed us with a purpose and a vision for the future.

Before reading the scripture

Last week, we saw how Paul ended the section with a reminder that all of us, including himself, will face judgment for what we’ve done in our bodies. As we continue with 2nd Corinthians, in today’s reading, Paul moves to an appeal for the reason he shares the gospel and focuses on God and not himself.

Because of our focus as believers of Christ, Paul teaches four truths here.

- We can have life in Christ.

- We should look at other people through Jesus’ eyes.

- We work as companions with Christ in God’s mission of reconciling himself to the world.

- And, in Christ, we can become more righteous.

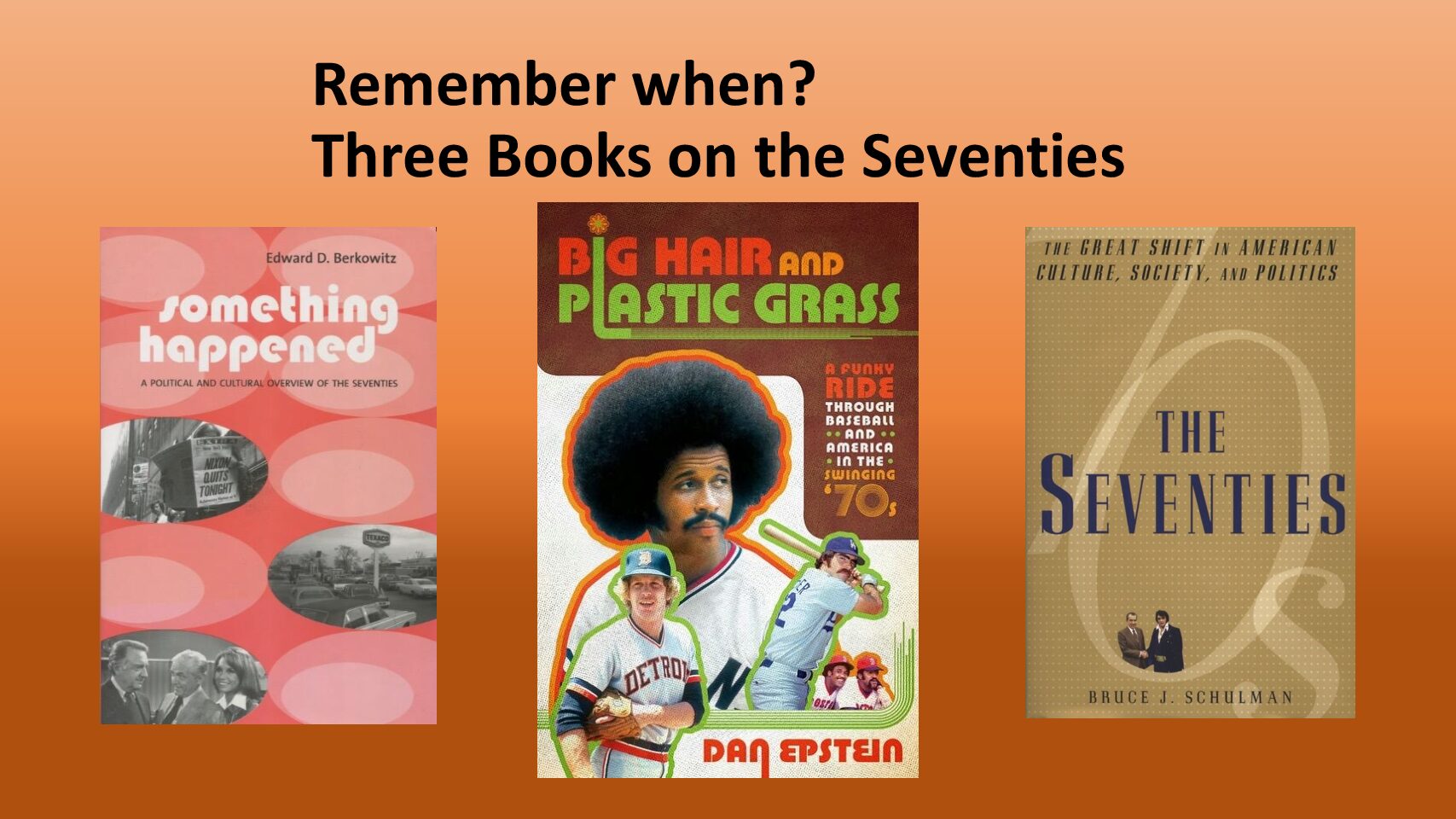

I recently listened to the book, Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging 70s. The 70s brought great change to baseball. Players began to look like the rest of America with long hair. AstroTurf took over ballparks. The designated hitter became a reality. But it was also a good decade for baseball if you were a Pirate’s fan. They were almost always in contention and won the World Series in ‘71 and ‘79.

The ‘79 series featured Willie Stargell, a great ball player. A few years later, when I would sit in the cheap seats in the upper deck of Three River Stadium, there would be stars marking where he smacked home runs. Stargell was the spark for that team, but he always insisted on giving credit to the rest of the players. Yet, his teammates always gave the credit back to him.

“He taught us how to take what comes and then come back,” Dave Parker, another player on the team said. “He taught us how to strike out and walk away calmly, lay the bat down gently, then get up the next time and hit a home run. From him we learned not to get too high on the good days or too low on the bad days, because there are plenty of both in this game…”

I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest that Paul would have been a fan of the ’79 Pirates. At least he’d like their attitude. Don’t boost about yourself, Paul insists. Others can boost about you. And the only ones that really matters is God, who knows all, as well as our own conscience. We should ask ourselves, “Are we doing our best?”

For Paul, the focus is always on Christ, the one who died for us, so that we might have life in him. And for Paul, this life is not just in the world to come, but in the present. Because Christ gave his life, we are to live not for ourselves, but for him.

Because we live for Christ, we are to look at the world differently. We don’t look at one another from a strictly human point of view. We must see others as Christ sees us, overlooking their flaws and seeing their God-given potential. This means we don’t look at others with envy or disdain, but with compassion and love.

“Comparison kills spirituality, John Ortberg wrote in the book I mentioned earlier.[2] If we compare ourselves to one another, whether we look up to or down on them, we’re doomed. For God didn’t create me to be you or you to be me. God creates us unique and the only comparison that we’re to make is to compare ourselves to our Savior, a mirror in which we will all see our shortcomings.

But thankfully, we will also all experience the accepting and loving smile of a forgiving Savior. Yes, he wants us to improve our lives, but doesn’t want us to be burdened with guilt or to make us into something we’re not.

So, Paul suggests we not evaluate people from a human point of view or, as translated in The Message “by what they have or how they look.” But you know, that’s not an easy lesson to learn.

One of the wonders of Facebook is that it has allows us to renew old friendships of people we’ve not seen or talked to in decades. For me, some of these people became good friends even though we weren’t close when we were younger. We knew each other but didn’t hang out a lot. Yet, now we’re all older, we find things we have in common.

Joseph was one such guy I got to know better, who sadly died four years ago. When visiting my parents, we’d often together for coffee or over a beer and talk. I confessed to him once that when we were in Junior High, I was envious of him and his friends in the band. He couldn’t believe it and went on to say, to my shock, how he was envious of me and me and those I ran around with. Truth be known, we’d both been better off if we hadn’t worried about others and just been ourselves. But that’s a hard lesson when you’re a teenager. But as we mature as disciples, it is a lesson we must learn. For we must see people as Jesus sees them.

Paul’s second point also needs to be considered. Not only are we not to judge others by human standards, but we’re also to realize that we’re not who we should be. That’s the purpose of comparing ourselves with Christ; for in Christ, we see our shortcomings and our need for both mercy and change. Looking at Christ, we see the need for conversion, to change into something new.

There must be a new creation, something we can’t do ourselves. Only God has such power to wash us clean and to change us. It’s important we see the tie Paul makes here between Christ and a new creation for we can’t recreate ourselves. I can change clothes or find a hair piece, but that’s not what Paul means. We must be recreated in Christ!

We can’t recreate ourselves; we need God’s help if we’re going to find new life in Christ. In Christ, we’re made new because we are reconciled with God. Our sins are not held against us because Christ takes them on himself.

In coming to Christ, we are made right with God, but it doesn’t end there. Remember, there is a purpose in all this… We’re made right with God, not just to get into heaven. Surely, that’s important, but it’s not the primary purpose. We’re made right with God first, then we’re to go out and reconcile others to ourselves. We become an extension in God’s work of reconciliation; it starts with Jesus and then flows through us into the world. God wants us to join in his work. That’s our call as Christians.

In verse twenty, we learn we’re Christ’s ambassadors. An ambassador is a good description, for an ambassador doesn’t represent his or her own interest; but the interest of his or her country. When the President appoints an ambassador to another country, they are not told to go and do what they think is best. They’re to represent our interest and our values to a foreign country. Likewise, as followers of Jesus, we represent not ourselves, but his kingdom! We are to show a foreign world the values of the heavenly kingdom to which we belong.

This means that our work as Christ’s disciples isn’t limited to what we do here, on Sunday morning. Our work is to be about showing godly values—in our families, our places of work, at the marketplace, or with our neighbors. Wherever we find ourselves, we are to be a living example of what it means to be a new creation in Christ.

And finally, in our last verse, Paul suggests all of this—our new lives in Christ, our seeing others in Christ’s eyes, our work of reconciliation—is a part a greater plan of us becoming more righteous. As we focus on Christ, we become more like him. That’s what the gospel is about.

“To Jesus Christ, who loves us and freed us from our sins by his blood and made us to be a kingdom, priest of his God and Father, to him be the glory and dominion forever and ever.[“3] Amen.

[1] John Ortberg, the me I want to be: becoming God’s best version of you (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010).

[2]Ortberg, 25.

[3] Revelation 1:5-6.