Merry Christmas everyone. Today was beautiful in South Georgia, a nice day for a walk with the dog, after opening present, playing a new board game (Ticket to Ride: Rails and Sails), and continually snacking on ham. For the past few days, we’ve experienced a deluge (6 inches of so of rain). But yesterday afternoon, the clouds dispersed in times for us to line the church driveway with luminaries for our evening service. Our sanctuary is most beautiful when decorated and filled with candles. Unfortunately, I’ve been fighting a head cold for the past week, but thankfully I was on an uptick yesterday, which made the evening much more pleasant. I will work tomorrow and then be on vacation for the rest of the year. But I do have a few more post. Below is my message for the candlelight service last night.

Christmas Eve Meditation 2019

Jeff Garrison

Bethlehem wasn’t a thriving town. It wasn’t the capital. It was off the beaten path. It’d seen its better years as Jerusalem grew and became the place to be. When you entered the city limits, there might have been a commentative sign acknowledging their favorite son, David, who went on to be the King of Israel. But I bet there were some who still harbored ill feelings toward David. He was the one who put Jerusalem on the map, positioning the Ark of the Covenant on the spot where Solomon would build the temple. Since those two, David and Solomon, almost a 1000 years earlier, Jerusalem prospered while Bethlehem slipped into a second-rate town.

Bethlehem was the type of town easily by-passed or driven through without taking a second glace. It might have had a blinking stoplight, or maybe not, like the towns we drive through when we get off the interstate.

Bethlehem could have been a setting for an Edward Hopper painting. He’s mostly known for “Nighthawks” a painting of an empty town at night with just a handful of lonely people hanging out in a diner. It’s often been parodied in art, with folks like James Dean and Marilyn Monroe sitting at counter. But all his paintings are sparsely populated, providing a sense that time has passed his urban landscapes by. Or maybe the town could be a setting for a Tom Wait’s song—the roughness of his voice describing lonely and rejected people, struggling through life.

In many ways, Luke sets up Bethlehem by placing the birth of the Prince of Peace in a historical context. In Rome, we have Augustus, the son of Julius Caesar. Some twenty-five years earlier, he had defeated all his enemies and the entire empire is now at peace. The glory of Rome far outshines even Jerusalem and makes Bethlehem seem like a dot on a map. Caesar has the power that can be felt in a place like Bethlehem, but he probably never even heard of the hamlet. And, of course, the peace Rome provides is conditional. This peace is maintained at the sharp points of its Legion’s spears and swords and, for those who would like to challenge the forced peace, the threat of crucifixion. Luke also tells us Quirinus is the governor of Syria.

Those rulers are in high places. They dress in fancy robes, eat at elaborate banquets, and live in lavished palaces. They aren’t bothered by the inconvenience their decrees place on folks like Mary and Joseph. This couple is one of a million peons caught up in the clog of the empire’s machinery. If the empire says, jump, they ask how high. If the empire says go to their ancestral city, they pack their bags. It’s easy and a lot safer to blindly follow directions than to challenge the system. So, Mary and Joseph, along with others, pack their bags and head out into a world with no McDonalds and Holiday Inns at interchanges. For Mary and Joseph, they head south, toward Bethlehem.

If there were anyone with even less joy than those who lived or stayed in Bethlehem, and those who are making their way to the home of their ancestors, ancestors who may not have lived there for generations, it would be the shepherds. The sheepherders are near the bottom of the economic ladder. They spend their time, especially at night, with their flocks out grazing. The sheep are all they have. They have to protect them. They can’t risk a wolf or lion eating one of their lambs. So, they camp out with the sheep, with a staff and rocks at hand to ward off any intruder. They don’t even like going to town because people look down on them and complain that they smell.

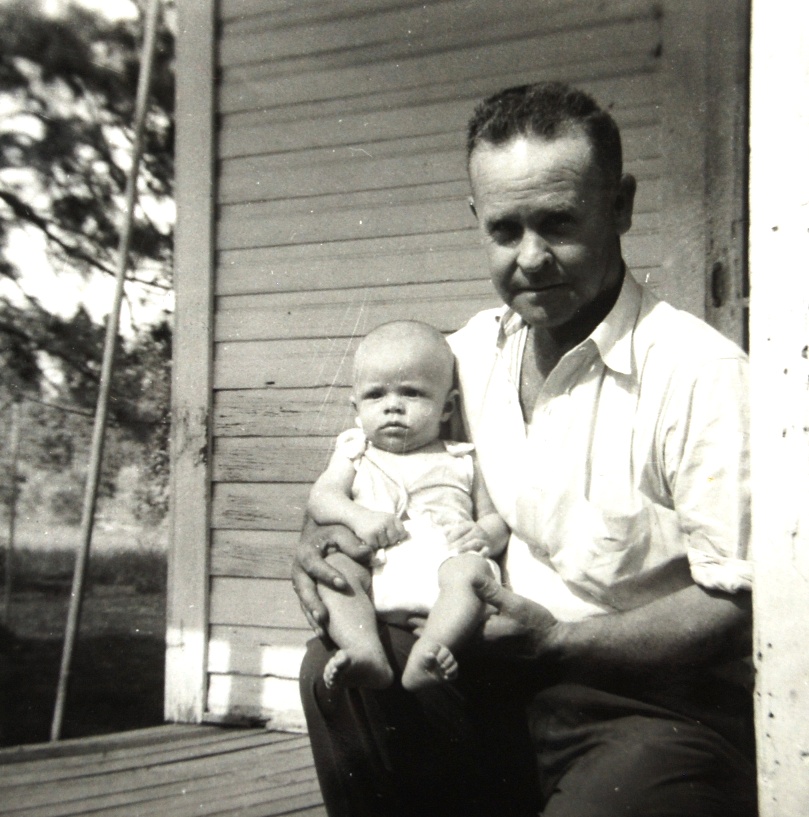

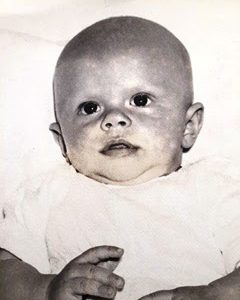

You can’t get much more isolated than this—a couple who can’t find proper lodging in Bethlehem, with the wife that’s pregnant, and some shepherds watching their flocks at night. But their hopelessness quickly changes as Mary gives birth and places her baby in a manger. There is something about a baby, a newborn, which delights us all. Perhaps it’s the hope that a child represents. Or the child serves as an acknowledgement that we, as a specie, will live on. While birth is a special time for parents and grandparents, an infant child has a way to melt the hearts of strangers who smile and make funny faces and feel blessed if the mother allows them to hold the child for just a moment.

This child that comes into this town and brings joy. Joy comes not just to the parents, but also to the angels. The angels share the joy with the shepherds. The shepherds want in on the act, so they leave their flocks and seek out the child. All heaven is singing and sharing the song with a handful of folks on earth. The shepherds also are let on the secret that, so far, only Mary and Elizabeth and their families share. This child, who is to be named Jesus, which is the same word that in the Old Testament is translated as Joshua, is coming to save the world. Soon, in a few generations, the song will spread around the known world.

And for this night, the sleepy hamlet of Bethlehem is filled with joy. The darkness cannot hide the joy in the hearts of this young mother and father and the shepherds. Something has changed. Yes, a child has been born. But more importantly, this child is the incarnation. God has come in the flesh, in a way that we can understand. God has come in a way to reach all people, from the lowly shepherds, to the oppressed people on the edge of the empire, to all the world. This child, whose birth we celebrate, has brought joy to the world.

Friends, as we light candles and recall that night in song, may you be filled with the joy of hope that comes from placing our trust in Jesus. Amen.

©2019

The holiday stands in contrast to the birth of the Prince of Peace, as it was with a woman shopping in one of those big city department stores. It was a multi-floored building, with escalators and elevators and an entire floor devoted to toys. To her four and six-year-olds, it seemed like heaven. The mother was reminded of another place. Her kids kept singing the “I want this” song over and over. On every aisle they discovered a new “I gotta have” toy. Frazzled and about to come unglued, the lady finally paid for her purchases. She dragged the bags and her two kids to the elevator. The door opened. She and the kids and the presents squeezed in. When the door closed, she let out a sigh of relief and blurted, “Whoever started this whole Christmas thing should be found, strung up and shot!” From the back of the elevator, a calm quiet voice responded, “Don’t worry, madam, we already crucified him.”

The holiday stands in contrast to the birth of the Prince of Peace, as it was with a woman shopping in one of those big city department stores. It was a multi-floored building, with escalators and elevators and an entire floor devoted to toys. To her four and six-year-olds, it seemed like heaven. The mother was reminded of another place. Her kids kept singing the “I want this” song over and over. On every aisle they discovered a new “I gotta have” toy. Frazzled and about to come unglued, the lady finally paid for her purchases. She dragged the bags and her two kids to the elevator. The door opened. She and the kids and the presents squeezed in. When the door closed, she let out a sigh of relief and blurted, “Whoever started this whole Christmas thing should be found, strung up and shot!” From the back of the elevator, a calm quiet voice responded, “Don’t worry, madam, we already crucified him.”

The glue that holds this passage together is the Holy Spirit. In a way, the Holy Spirit is like divine matchmaker. The Spirit impregnates Mary, bringing life into her womb and setting off this genesis, this new beginning. The Spirit also works on the other side of the equation, with Joseph, getting him to buy into the plan. Through the dream, Joseph is informed of Mary’s righteousness and of God’s plan for the child she carries. And when Joseph awakes, he decides not to dismiss Mary, but to go ahead with the wedding. They’ll marry and together raise this child and participate in God’s plan for reconciling himself to a fallen world. It’s a good thing Joseph listened to God in this dream.

The glue that holds this passage together is the Holy Spirit. In a way, the Holy Spirit is like divine matchmaker. The Spirit impregnates Mary, bringing life into her womb and setting off this genesis, this new beginning. The Spirit also works on the other side of the equation, with Joseph, getting him to buy into the plan. Through the dream, Joseph is informed of Mary’s righteousness and of God’s plan for the child she carries. And when Joseph awakes, he decides not to dismiss Mary, but to go ahead with the wedding. They’ll marry and together raise this child and participate in God’s plan for reconciling himself to a fallen world. It’s a good thing Joseph listened to God in this dream. Joseph’s dream shows us the importance of listening to God and when we listen to God and follow his path, we will often find peace. Let me clarify. I don’t think listening to God means trying to understand all the dreams of our sleep. Often our dreams are a way that our minds sort out stuff. Instead of investing large amounts of time trying to understand what our dreams are telling us, we need prepare ourselves to hear God’s voice by studying Scripture, by praying and by being open to hear God by whatever means he comes to us. God’s word can come many ways: in our sleep, through a thought we have while walking or driving, or in a conversation. What’s important is that we know God’s word enough to make sure what we hear is from God. Notice in our account today how Joseph is reminded of the prophecies in Scripture. For him, that was assurance God was behind this.

Joseph’s dream shows us the importance of listening to God and when we listen to God and follow his path, we will often find peace. Let me clarify. I don’t think listening to God means trying to understand all the dreams of our sleep. Often our dreams are a way that our minds sort out stuff. Instead of investing large amounts of time trying to understand what our dreams are telling us, we need prepare ourselves to hear God’s voice by studying Scripture, by praying and by being open to hear God by whatever means he comes to us. God’s word can come many ways: in our sleep, through a thought we have while walking or driving, or in a conversation. What’s important is that we know God’s word enough to make sure what we hear is from God. Notice in our account today how Joseph is reminded of the prophecies in Scripture. For him, that was assurance God was behind this.

Earlier in the first chapter of Luke’s gospel, the angel Gabriel met Mary in Nazareth to give her the good news. However, I’m not sure that everyone saw this as good news. I am not even sure Mary saw it that way. After all, she was just a young woman. Tradition has it she was only 14 years old, and here’s this angel is talking about all of what this child she’s to carry will do. Mary wonders how it’s to happen and told that the Holy Spirit will fill her, and she’ll conceive. In addition, she’s told that her relative, the old barren Elizabeth, is also pregnant and will bear a son. God appears to be active with the oldest and the youngest.

Earlier in the first chapter of Luke’s gospel, the angel Gabriel met Mary in Nazareth to give her the good news. However, I’m not sure that everyone saw this as good news. I am not even sure Mary saw it that way. After all, she was just a young woman. Tradition has it she was only 14 years old, and here’s this angel is talking about all of what this child she’s to carry will do. Mary wonders how it’s to happen and told that the Holy Spirit will fill her, and she’ll conceive. In addition, she’s told that her relative, the old barren Elizabeth, is also pregnant and will bear a son. God appears to be active with the oldest and the youngest. “Girl, how’d you get yourself in this mess?” isn’t how Elizabeth greets Mary. Instead, she starts out praising Mary, wondering what she, Elizabeth, has done to deserve such a visit. She proclaims Mary as the most blessed of all women. Mary breaks out in song. She didn’t sing to Gabriel, at the heavenly encounter she had earlier. She sings when another person, one whom must have known as a kind older woman, confirms her status.

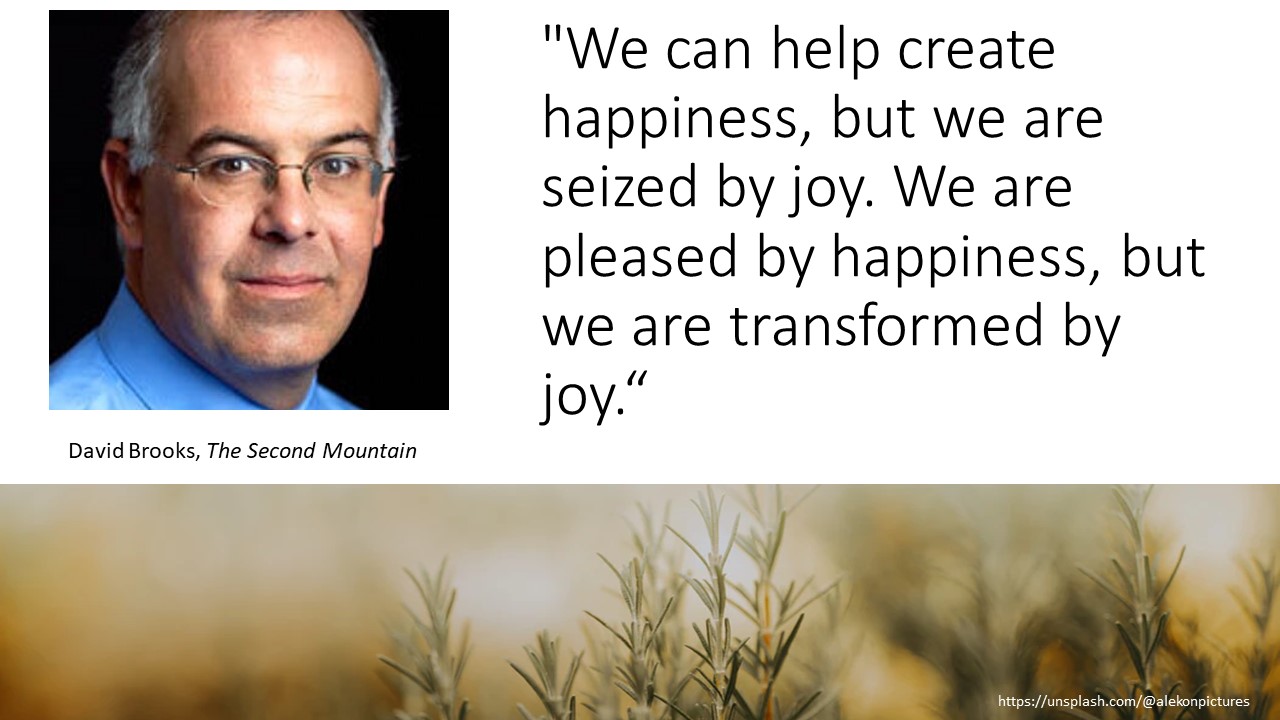

“Girl, how’d you get yourself in this mess?” isn’t how Elizabeth greets Mary. Instead, she starts out praising Mary, wondering what she, Elizabeth, has done to deserve such a visit. She proclaims Mary as the most blessed of all women. Mary breaks out in song. She didn’t sing to Gabriel, at the heavenly encounter she had earlier. She sings when another person, one whom must have known as a kind older woman, confirms her status. Mary is joyous, but not in the manner we think of joy. For us, joy is a child experiencing an ice cream cone for the first time or us witnessing the child’s wonder. Joy is a mother watching her son make a home run as a Little Leaguer. Joy is laugher at a good joke, the awe of a beautiful sunset without sand gnats, sitting around a fire telling stories when it’s not too cold, or the Pirates winning the World Series. All these things are great, but is this what joy really is? Or is it something deeper.

Mary is joyous, but not in the manner we think of joy. For us, joy is a child experiencing an ice cream cone for the first time or us witnessing the child’s wonder. Joy is a mother watching her son make a home run as a Little Leaguer. Joy is laugher at a good joke, the awe of a beautiful sunset without sand gnats, sitting around a fire telling stories when it’s not too cold, or the Pirates winning the World Series. All these things are great, but is this what joy really is? Or is it something deeper. When Jesus was at table with his disciples on the night before his crucifixion, he instructs his disciples and then says he’s telling them all this so that his joy will be in them, and that their joy will be complete.

When Jesus was at table with his disciples on the night before his crucifixion, he instructs his disciples and then says he’s telling them all this so that his joy will be in them, and that their joy will be complete. When Paul writes from prison to the Philippians, he tells them how he’s joyous when he prays for them and asks them to make his joy complete by being of the mind as Christ.

When Paul writes from prison to the Philippians, he tells them how he’s joyous when he prays for them and asks them to make his joy complete by being of the mind as Christ. This is unabashed joy; joy regardless of the situation. All is not well in the world, then or now, but we as believers are called to see beyond the present and to have faith in what God’s doing. We are called to be joyous and to have hope and to share our hope with others. In the long arch of history the impeachment of a President, a rogue nation like North Korea having rockets and weapons of mass destruction, and the eruption of a volcano in New Zealand (or heaven help us, if one blew up in Bluffton) isn’t the final word. For we believe God has things under control and even if we screw everything up and blow the planet to smithereens, God will not let that be the final word.

This is unabashed joy; joy regardless of the situation. All is not well in the world, then or now, but we as believers are called to see beyond the present and to have faith in what God’s doing. We are called to be joyous and to have hope and to share our hope with others. In the long arch of history the impeachment of a President, a rogue nation like North Korea having rockets and weapons of mass destruction, and the eruption of a volcano in New Zealand (or heaven help us, if one blew up in Bluffton) isn’t the final word. For we believe God has things under control and even if we screw everything up and blow the planet to smithereens, God will not let that be the final word. So, we go back to that young woman, pregnant and not yet married, in a world without social safety nets. You can’t be much more vulnerable than Mary, standing before Elizabeth. Yet she breaks out in this beautiful song that focuses on what God is doing. Mary doesn’t speak of what God is doing for her, personally, except for having chosen her. She’s not thankful for a new house, or car, or clothes or a servant. Her lot is not joyful by most definitions. She has this son that runs away at the age of 12.

So, we go back to that young woman, pregnant and not yet married, in a world without social safety nets. You can’t be much more vulnerable than Mary, standing before Elizabeth. Yet she breaks out in this beautiful song that focuses on what God is doing. Mary doesn’t speak of what God is doing for her, personally, except for having chosen her. She’s not thankful for a new house, or car, or clothes or a servant. Her lot is not joyful by most definitions. She has this son that runs away at the age of 12.

John Lane

John Lane

There were two preachers who, on their day off, enjoyed fishing. They were at a river next to a highway. Before sitting on the bank, where they’d watch their corks in the hope they’d be the tug of a fish on the line, they posted a sign. It read, “The end is near! Turn yourself around before it’s too late.”

There were two preachers who, on their day off, enjoyed fishing. They were at a river next to a highway. Before sitting on the bank, where they’d watch their corks in the hope they’d be the tug of a fish on the line, they posted a sign. It read, “The end is near! Turn yourself around before it’s too late.” I wonder about John’s message. It’s so harsh, maybe he should have toned down his words. Repeatedly, he talks of fire, and not the warming flames of a campfire, but the ominous fire like those recently experienced in California and Australia. “You brood of vipers,” he calls the religious leaders of the day. That doesn’t sound very loving, does it? Jesus would never say that, would he? Actually, he does; twice in Matthew’s gospel.

I wonder about John’s message. It’s so harsh, maybe he should have toned down his words. Repeatedly, he talks of fire, and not the warming flames of a campfire, but the ominous fire like those recently experienced in California and Australia. “You brood of vipers,” he calls the religious leaders of the day. That doesn’t sound very loving, does it? Jesus would never say that, would he? Actually, he does; twice in Matthew’s gospel. Law and gospel, they go together. To understand the story of scripture, we can’t just push off the “law” parts of the Bible and only focus on the gospel. The gospel makes no sense without the law. The gospel is about how God saves us from our failures, our sin. Those who listened to and were moved by John’s preaching were left with no choice but to confess their sins in order to begin the process of repentance, a word that means to turn around or to start in a new direction. They had to leave sin behind as they joyfully accept what God was doing in their midst.

Law and gospel, they go together. To understand the story of scripture, we can’t just push off the “law” parts of the Bible and only focus on the gospel. The gospel makes no sense without the law. The gospel is about how God saves us from our failures, our sin. Those who listened to and were moved by John’s preaching were left with no choice but to confess their sins in order to begin the process of repentance, a word that means to turn around or to start in a new direction. They had to leave sin behind as they joyfully accept what God was doing in their midst. But it all comes back to this. God is doing something new. With John the Baptist, God was paving the way for his Son to come on the scene and to teach people a new way to live and to be human. In order to prepare for something new, people must admit their own sinfulness and to realize that they long for something better. Of course, if we don’t think we need to be better, there’s a warning here. Judgment that comes from transgressing the law is a reality. So, do we ignore our sinfulness and die to the law? Or do we accept and confess our sinfulness and embrace the grace that Jesus’ offers? Those are our choices.

But it all comes back to this. God is doing something new. With John the Baptist, God was paving the way for his Son to come on the scene and to teach people a new way to live and to be human. In order to prepare for something new, people must admit their own sinfulness and to realize that they long for something better. Of course, if we don’t think we need to be better, there’s a warning here. Judgment that comes from transgressing the law is a reality. So, do we ignore our sinfulness and die to the law? Or do we accept and confess our sinfulness and embrace the grace that Jesus’ offers? Those are our choices. Advent is the time for us to prepare for the loving tenderness shown by Jesus. If God is redeeming this world, if God is promising a new heaven and a new earth, then we should want to be ready to receive this gift. But to receive the gift, we must leave the past behind. We have to be willing to examine deep within our souls and to offer up all that’s not godly so that we might be both cleansed of our sin and have the room to accept Christ into our hearts. We must be willing to allow ourselves to be transformed into something new and better. For Advent is a time not only to remember that Christ came, but that he will come again, and we must be ready.

Advent is the time for us to prepare for the loving tenderness shown by Jesus. If God is redeeming this world, if God is promising a new heaven and a new earth, then we should want to be ready to receive this gift. But to receive the gift, we must leave the past behind. We have to be willing to examine deep within our souls and to offer up all that’s not godly so that we might be both cleansed of our sin and have the room to accept Christ into our hearts. We must be willing to allow ourselves to be transformed into something new and better. For Advent is a time not only to remember that Christ came, but that he will come again, and we must be ready. We must not just prepare ourselves; we should prepare the church, which is, in the final events of history, to be the bride of Christ.

We must not just prepare ourselves; we should prepare the church, which is, in the final events of history, to be the bride of Christ. Is there loving joy in this passage that will lead to us “repeat the sounding joy”? Yes, there is, but we must get beyond the call to prepare, which John focuses on, and realize that God is doing a new thing. We trust in a God of resurrection. Even if the world destroys itself, God won’t let that be the final word. God wants to remake us. John’s role is to prepare us. Our role is to respond to John’s call to repentance so we might be open to what God is doing in our lives and in our fellowship. Confession and repentance may not in favor in today’s secular world, but in the church, it’s where we begin. All of us need to take a deep look at ourselves and then turn to God and fall on our knees… Amen.

Is there loving joy in this passage that will lead to us “repeat the sounding joy”? Yes, there is, but we must get beyond the call to prepare, which John focuses on, and realize that God is doing a new thing. We trust in a God of resurrection. Even if the world destroys itself, God won’t let that be the final word. God wants to remake us. John’s role is to prepare us. Our role is to respond to John’s call to repentance so we might be open to what God is doing in our lives and in our fellowship. Confession and repentance may not in favor in today’s secular world, but in the church, it’s where we begin. All of us need to take a deep look at ourselves and then turn to God and fall on our knees… Amen.

I will always be indebted to the congregation in Virginia City, Nevada, a place where I first experienced ministry on my own as a student pastor for a year. The church on the Comstock, at least in the modern era, has always been small. But there was something about the fellowship of that group that made it an attractive place for all kinds of people. The people in the church worked hard together, keeping the church going, which was quite a task in a wooden building built in 1866. But they also worked hard to help one another. And they tried to help others, sending clothes to an orphanage in Mexico and collecting food for a pantry in Carson City.

I will always be indebted to the congregation in Virginia City, Nevada, a place where I first experienced ministry on my own as a student pastor for a year. The church on the Comstock, at least in the modern era, has always been small. But there was something about the fellowship of that group that made it an attractive place for all kinds of people. The people in the church worked hard together, keeping the church going, which was quite a task in a wooden building built in 1866. But they also worked hard to help one another. And they tried to help others, sending clothes to an orphanage in Mexico and collecting food for a pantry in Carson City. The congregation Luke describes here near the beginning of the book of Acts wasn’t spectacular. It wouldn’t be considered particularly successful according to modern business practices. The fellowship didn’t include the leading folks of Jerusalem. Everyone was poor and marginalized. They didn’t have any glitzy advertising or even a fancy sign out front. After all, they tried to blend in and not stand out because there were those didn’t appreciate their message. But, despite all this, there was something magnetic about this community. They were generous and gracious. They were willing to help each other and to forgive others for the wrongs they’ve done because they’d experienced forgiveness in Jesus Christ. It was this magnetic appeal that drew folks to the church. Why else would someone risk persecutions and isolation by becoming a Christian?

The congregation Luke describes here near the beginning of the book of Acts wasn’t spectacular. It wouldn’t be considered particularly successful according to modern business practices. The fellowship didn’t include the leading folks of Jerusalem. Everyone was poor and marginalized. They didn’t have any glitzy advertising or even a fancy sign out front. After all, they tried to blend in and not stand out because there were those didn’t appreciate their message. But, despite all this, there was something magnetic about this community. They were generous and gracious. They were willing to help each other and to forgive others for the wrongs they’ve done because they’d experienced forgiveness in Jesus Christ. It was this magnetic appeal that drew folks to the church. Why else would someone risk persecutions and isolation by becoming a Christian? I recently read an article on why we need to make a weekly commitment to attend church. I’ll post this article I my next e-news. It was written by a young widow who describes the church as “the sweetest fellowship this side of heaven.” Her husband died suddenly one night after having been taken to the hospital by an ambulance for shortness of breath. She was left with seven kids. Before leaving the hospital, she called a friend from church. By the time she was home, the friend was there to sit with her. Others came in to grieve, to bring meals, to help clean the house, fix broken appliances and cars, and to minister to and pray for her and her children. The church is not always perfect, she notes. At times, the church can be even cruel. But when we live up to our calling to reflect Jesus’ face to the world, we demonstrate what was described in our passage today. The church can be the sweetest fellowship this side of heaven.

I recently read an article on why we need to make a weekly commitment to attend church. I’ll post this article I my next e-news. It was written by a young widow who describes the church as “the sweetest fellowship this side of heaven.” Her husband died suddenly one night after having been taken to the hospital by an ambulance for shortness of breath. She was left with seven kids. Before leaving the hospital, she called a friend from church. By the time she was home, the friend was there to sit with her. Others came in to grieve, to bring meals, to help clean the house, fix broken appliances and cars, and to minister to and pray for her and her children. The church is not always perfect, she notes. At times, the church can be even cruel. But when we live up to our calling to reflect Jesus’ face to the world, we demonstrate what was described in our passage today. The church can be the sweetest fellowship this side of heaven. Friends, today we receive our estimate of giving offerings for 2020, which is a sign of one half of that last question—how generous we are. We are encouraged to grow in generosity. As Vic Bell suggested last week, we’re to take a step toward being more generous, as we strive to become the church described in Acts. I pray that you will be generous and continue to take steps in this direction. But just as important as generosity is, don’t forget to be graciousness. On your walk with Christ, show grace to one another, just as God has been gracious with us. Realize what God has done and commit yourselves to do what? Say it after me… To be more being generous and gracious. Amen.

Friends, today we receive our estimate of giving offerings for 2020, which is a sign of one half of that last question—how generous we are. We are encouraged to grow in generosity. As Vic Bell suggested last week, we’re to take a step toward being more generous, as we strive to become the church described in Acts. I pray that you will be generous and continue to take steps in this direction. But just as important as generosity is, don’t forget to be graciousness. On your walk with Christ, show grace to one another, just as God has been gracious with us. Realize what God has done and commit yourselves to do what? Say it after me… To be more being generous and gracious. Amen. Bonnie Jo Campbell, Once Upon a River (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 348 pages.

Bonnie Jo Campbell, Once Upon a River (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 348 pages.