Over the past few years, I have been concerned on the lack of civility in our public lives. We see it in politics, in grocery stores, and on the highways. Before COVID, I was activity attempting to foster conversation about civility. It’s needed in our world. Because of my interest, a parishioner in one of my churches gave me this book.

Peter Wehner, The Death of Politics: How to Heal Our Frayed Republic After Trump (New York: HarperCollins, 2019), 264 pages including notes.

The death of politics sounds like a good idea. But is it? Politics is how we work out our differences without resorting to violence. If politics dies, so does our democratic society.

Peter Wehner is a life-long Republican and a conservative who served in Reagan’s and both Bush’s Presidential administrations. He’s concerned over the current state of our political discourse, believing that we are on a dangerous road. We look with contempt at those with whom we disagree. We despite politics when we don’t get our way. We’re angry. Many people have lost hope in the political process to help guide us peacefully out of this situation. In this book, Wehner begins discussing how we’ve gotten into such a position as a society. While he was concerned over Donald Trump, Wehner acknowledges this slip has been going on in America at least since Vietnam. What gave Trump his power was his ability to harness such negative energy.

This is not really a book about Trump. Wehner’s concerns are much deeper. He begins with a discussion on how politics is a noble calling. Then he delves into how we found ourselves into a position where we hold politics in disdain. Before offering suggestions on how to make things better, Wehner provides a civil lesson in how politics should work. He draws on the political insights of Aristotle, John Locke, and Abraham Lincoln. As a conservative, he also pulls ideas from the British statesman, Edmund Burke, along with many Americans conservatives, especially Reagan and William Buckley.

My favorite part of the book are the middle chapters (4 and 5), titled “Politics and Faith” and “Words Matter.” While Separation of Church and State is enshrined in the Constitution, America is fundamentally a religious country. The founders of our nation, while wanting to keep the church and state separate, “argued that religion was essential in providing a moral basis for a free society” (66). Wehner builds upon the Biblical foundation that we’re all created in God’s image. Recalling the words of Martin Luther King, Jr, he reminds that church that it is not the master nor the servant of the state, “but the conscience of the state” (88). He is very critical of many within the evangelical circles and of Trump. He suggests that Trump’s morality is more Nietzschean than Christian and that many evangelicals are “doing more damage to the Christian witness than the so-called ‘New Atheists’ ever could” (80-81).

Wehner ends the chapter with four suggestions for Christians in today’s political climate: 1. Begin with Jesus, with what he taught and the example he modeled. 2. Articulate a coherent vision of politics, informed by a “Christian moral vision of justice and the common good.” 3. Model “moving from anger to understanding, from revenge toward reconciliation, from grievance toward gratitude, and from fear toward trust and love.” And finally, 4., “treat all people as ‘neighbors they are to love (86ff).’” Interestingly, in his acknowledgements, he thanked Philip Yancey (whose memoir I reviewed a few weeks ago) for helping him with this chapter.

Chapter five, on words, he begins recalling many of John Kennedy’s speeches. As a student of politics, even though a Republican, he noted the eloquence of Kennedy’s style that launch a decade in which America made great gains ending up on the moon. It is interesting, too, how Presidents tend to be remembered by their words more than their policies, of which he provides examples across political spectrum and ages. Drawing from David Reynold’s book, Mightier than the Sword, which looked at the impact of Harriett Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin on changing the discourse over slavery in America, Wehner makes the case that words can help move a society in a more noble manner.

Wehner also shows how words and rhetoric can be misused. Here, he primarily focuses on how words can help foster racial biases toward others. He also notes our tendency toward “confirmation bias,” where we tend to listen and read only that which confirms our own prejudices. He is critical with how words are used as weapons, and how truth no longer matters as long “our side” wins. Wehner suggests as an antidote to our bias, that we read widely. He ends this chapter drawing from the English author, “George Orwell, especially his essay “Politics and the English Language.” He suggests that reclaiming language is necessary for us to reclaim politics (139).

In chapter 6, Wehner turns to the topic of moderation, compromise, and civility. Here he begins to offer more suggestions with how we might live together peacefully despite our differences. The goal of society is not to have everyone think the same, but to allow people coexistence. Drawing upon the ideas of James Madison, he recalls how the founders of our constitution understood humanity as flawed but also capable of virtue and self-government. Sadly, he sees our current situation as pushing us in the opposite direction, toward alienation from one another. To reverse direction, we need the constitution’s system of checks and balances to work. He makes a case for moderation to temper the populist anger that judges others to be “evil and irredeemable” (151). Moderation understands the complexity of our world and “distrusts utopian visions and simple solutions” (153). When we are moderate in our ideas, we are willing to compromise (which isn’t a bad word, but how we settle differences). Finally, we need to be civil toward one another. Here, Wehner draws from his faith, quoting the Apostle Paul advice to the Colossians, “Let your conversations be always full of grace…” and from his “fruits of the Spirit” which he encouraged the Galatians to demonstrate in their lives (163).

While Wehner encourages citizens to support candidates for office who model moderation, compromise, and civility, he also realizes that the anger within society has often been fueled by outside sources. He calls for a blockage of foreign web bot sites that spreads false information and encourage civil unrest. Organizations like “Better Angels” and “Speak Your Peace”, as well as columnists like David Brooks and Yuval Levin are offered as good examples that will lead us to a more civil society.

In his final chapter, Wehner makes the case for hope. He reminds Americans of the social regression between 1960 and 1990, which saw a 500% increase in violent crimes, 400% increase in out of wedlock births, increase in children on welfare, teenage suicide, and divorce. But then, things started to improve, with a decrease in these areas. But we’ve forgotten how things should work. He chides conservatives for focusing only on the cost of government and not on its effectiveness. Wehner also acknowledges his own failures within George W Bush’s administration in relation to Iraq, admitting that they were wrong in their assumptions. He also admits that its easier for him to be a “Monday morning quarterback” and to critique from the outside than the inside. Finally, he encourages us to care enough to act and to move beyond our current “bread and circus” style of government.

One of the keys in being civil, which Wehner recognizes, is that it must come internally. Civility won’t be achieved with conservatives demanding it of liberals, or liberals demanding it from conservatives. Instead, we all must realize that more is at stake. The soul of our nation is in danger. What can we do as individuals to help change the tenor of the political conversation? Those of us who are followers of Jesus should be at the forefront in displaying civility. I encourage others to read this book.

My review of other books of similar interest:

P. M. Forni, The Civility Solution: What To Do When People are Rude

Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal

W. Singer and Emerson T. Brooking, LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media

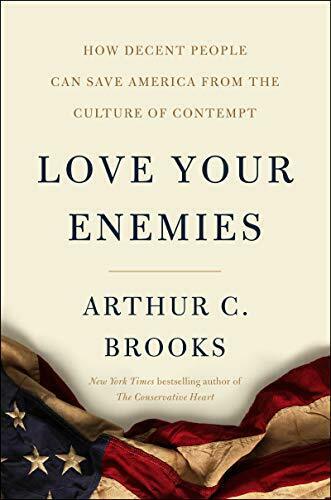

Arthur Brooks, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America

John Kasich, It’s Up to Us: Ten Little Ways We Can Bring About Big Change

N. T. Wright, Surprised by Scripture: Engaging Contemporary Issues (New York: HarperOne, 2014), 223 pages including a scripture index.

N. T. Wright, Surprised by Scripture: Engaging Contemporary Issues (New York: HarperOne, 2014), 223 pages including a scripture index.

Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018), 272 pages including notes and an index.

Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018), 272 pages including notes and an index. Arthur C. Brooks, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America for the Culture of Contempt (HarperCollins, 2019), 243 pages, index and notes.

Arthur C. Brooks, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America for the Culture of Contempt (HarperCollins, 2019), 243 pages, index and notes.