Jeff Garrison

Mayberry and Bluemont Churches

February 16, 2025

Jeremiah 17:1-13 (14-18)

At the beginning of worship:

Delivered to my inbox every day is a new word. I generally look at the word. Often, I don’t know the word, I’ll look at the meaning realize it’s so obscure I’ll never use it. But this week, one of the words made me ponder the passage I’m preaching on today. Actually, it’s two words, Amor Propre. Rousseau, the 17thCentury French philosopher, coined the term which means “self-love,” especially a love which comes from the adoration of others who make us feel important.[1] Now that I used it, I’ll never use it again.

As followers of Jesus, the only one who truly matters and provides us with self-worth is God. Seeking such approval from everyone else, to quote Jeremiah, is to trust in mere mortals, as we turn away from the Lord.

Before reading the scripture:

Since Christmas, I’ve been preaching from the Old Testament reading from the lectionary. This will be the last Sunday doing this. Next week, God willing, I’ll return to Mark’s gospel. Hopefully, we’ll finish up Mark between then and Palm Sunday. While I really like building upon the previous week’s passage as I preach through a book, it’s also refreshing to occasionally focus on odd passages as I’ve done for the past month.

Today, we’re back in Jeremiah. The lectionary only calls for the reading from the heart of this passage, verses 5 through 10. That cuts out a good deal of the passage’s power. I am going to read the entire section which starts with verse 1 and goes through verse 18. But I’ll save the last 5 verses for the prayer at the end of the sermon.

In some ways, this is an unusual section for Jeremiah. Unlike many other places, we do not hear from Jeremiah in first person, until his prayer at the end. Instead, this section begins with God speaking through the prophet, indicting Judah. Then, we hear a series of proverbs which start off sounding like Psalm 1. Many scholars think that instead of Jeremiah writing these himself, he borrowed from traditional proverbs.[2] Kind of like how we might quote Ben Franklin or Mark Twain. In the Psalm and in verses 5 to 8, two trees are used as a metaphor of those who place their trust in God’s hands and those who trust human hands. Jeremiah continues by reflecting on the human heart and giving a warning against unearned gains.

All this sounds kind of depressing, doesn’t it. But like a good lament, our passage focuses back on God and the hope offered to those who trust in God. Finally, I’ll read the ending of the passage at the end of the sermon, as a prayer. There, we’ll hear Jeremiah’s plea for relief. Let’s now listen to this passage.

Read Jeremiah 17:1-13

Why do humans behave so badly? I wonder if Jeremiah asked this question. After all, he’s addressing a people guilty of forsaking their first love, the God in whom they have made a covenant to worship, honor, and obey in exchange for prosperity and protection.

This passage opens with an indictment. This sounds like a judge sentencing a guilty criminal. Judah’s sin has been engraved with a diamond pointed chisel onto granite hearts and on the horns of their altars. They are guilty. Of course, the altars are not the altar to God in the temple in Jerusalem, but altars and scared poles placed on high hills honoring the ancient Canaanite deities: Baal and Ashera.[3] Such idolatry breaks their covenant with God.

The deal was that if they placed their trust in God, the Lord would watch out for them and protect them. But they’ve broken this trust. We’re also often reminded in the Old Testament of God’s jealously.[4] We see God’s jealously expressed here. God responds to their lack of trust by giving their enemies their treasures and allowing the people to once again be slaves.

In verse five, God identifies the people’s sin, in addition to idolatry, as trusting in themselves and in other humans. The people may look to a powerful Rambo-like character or see the shiny spears and shields of their army in formation and think they’re safe. But that’s not safety, God says. For they’ve turned their hearts from the Lord. Human power is like a shrub in the desert.

Here, the wording of the indictment echoes Psalm 1, which contrasts the faithful and wicked as two different trees. The Psalm first highlights those who do not follow the path of the wicked. Comparing them to trees planted by streams of water, they thrive. The wicked are like chaff which cannot withstand the wind and the judgment which comes upon it.

In Jeremiah, unlike Psalm 1, the wicked are dealt with first. The cursed are those who trust in human strength. They’re like a shrub in the desert. John Calvin, who uses the metaphor of God as the fountain of all that’s good,[5] as we see in this passage, suggests that this particular shrub spoken of by Jeremiah, appears alive but its roots have dried up. Unable to drink from God’s fountain, Judah waits for justice.[6]

On the contrast are the blessed, those who trust in the Lord. Like a tree by a stream, they thrive. Because they have deep roots, they don’t even fear drought or heat, for they can tap into life-giving water.

Notice that for both metaphorical trees, trouble will come. They’ll be hot winds and droughts. The one who doesn’t trust in God have no roots to sustain life when trouble arises. The one does place his or her trust in God will survive the trials.

Next, our passage speaks of the devious and perverse hearts. As I spoke at the beginning of last week’s service, we live in a world which often confuses feelings and actions.[7] We probably don’t feel our hearts are devious and perverse. This may sound harsh. But it reflects a realization that we often look to our own well-being instead of trusting in God to do what is right.

To quote Calvin again, the heart is a perpetual factory of idols.[8]We find it easier to trust in ourselves or those who promise protection. We with our own strength, or those we idolize, may deliver in the short run. But we’ll so give up, or our contract with others will require us to compromise our morals. Sooner or later, such situations will fail us.

Our passage asks the rhetorical question as to who can understand the human heart. Then it answers itself, reminding us that God searches both our hearts and minds, rewarding us for the fruits of what we do and think. We must remember that while in this life, evil may seem to go unpunished, God sees and there is a life to come. We may not always see the consequences, but we worship a God of justice.

In the next proverb, we catch glimpse of such justice in this world. A partridge warms and hatches an egg it did not lay. To say it in another way, it hatched an egg that did not belong to it. Obviously, it would not be another partridge and as it grows would seek out its own family, abandoning the partridge. This observation from the natural world is linked to those who amass wealth unjustly.

After providing these bits of wisdom, our song shifts focus to God, reminding those who hear these words of the danger of ignoring God, who is the fountain of living water.

Our hope is with the Lord. Jeremiah understood this as we see in his prayer at the end of this passage. I will close reading verses 14 to 18. Consider it a prayer not just for the prophet, but for all of us. For we need to turn from that which is mortal and center our lives in God the Father and our Lord Jesus Christ.

Let me warn you that the ending of this prayer may seem harsh. We must remember that Jeremiah was a persecuted man and those persecuting him were guilty of not trusting in God, but in their own strength. And they used their strength to torment Jeremiah. The prophet, trusting in God’s justice, demands it and asks that he be spared. Let us pray with Jeremiah:

Heal me, O Lord, and I shall be healed;

save me, and I shall be saved,

for you are my praise.

See how they say to me,

“Where is the word of the Lord?

Let it come!”

But I have not run away from being a shepherd in your service,

nor have I desired the fatal day.

You know what came from my lips;

it was before your face.

Do not become a terror to me;

you are my refuge in the day of disaster;

Let my persecutors be shamed,

but do not let me be shamed;

let them be dismayed,

but do not let me be dismayed;

bring on them the day of disaster;

destroy them with double destruction! Amen.

[1] https://worddaily.com/words/Amour-Propre/

[2] R. E. Clements, Jeremiah: Interpretation, A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1988), 107.

[3] Clements, 105.

[4] See Exodus 20:5, 34:14 and Deuteronomy 4:24, 5:9, 6:15. See also Joshua 24:19.

[5] See B. A. Gerrish, Grace and Gratitude: The Eucharistic Theology of John Calvin (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993), especially chapter 2.

[6] John Calvin, Commentary on Jeremiah and Lamentations, vol 1 (Grand Rapids, Baker, 1979), 351-352. As quoted by Walter Brueggemann, Jeremiah 1-25, To Pluck Up, to Tear Down (Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1988), 151.

[7] https://fromarockyhillside.com/2025/02/09/isaiahs-tough-message/

[8] John Calvin, Institute of the Christian Religion, 1.11.8.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

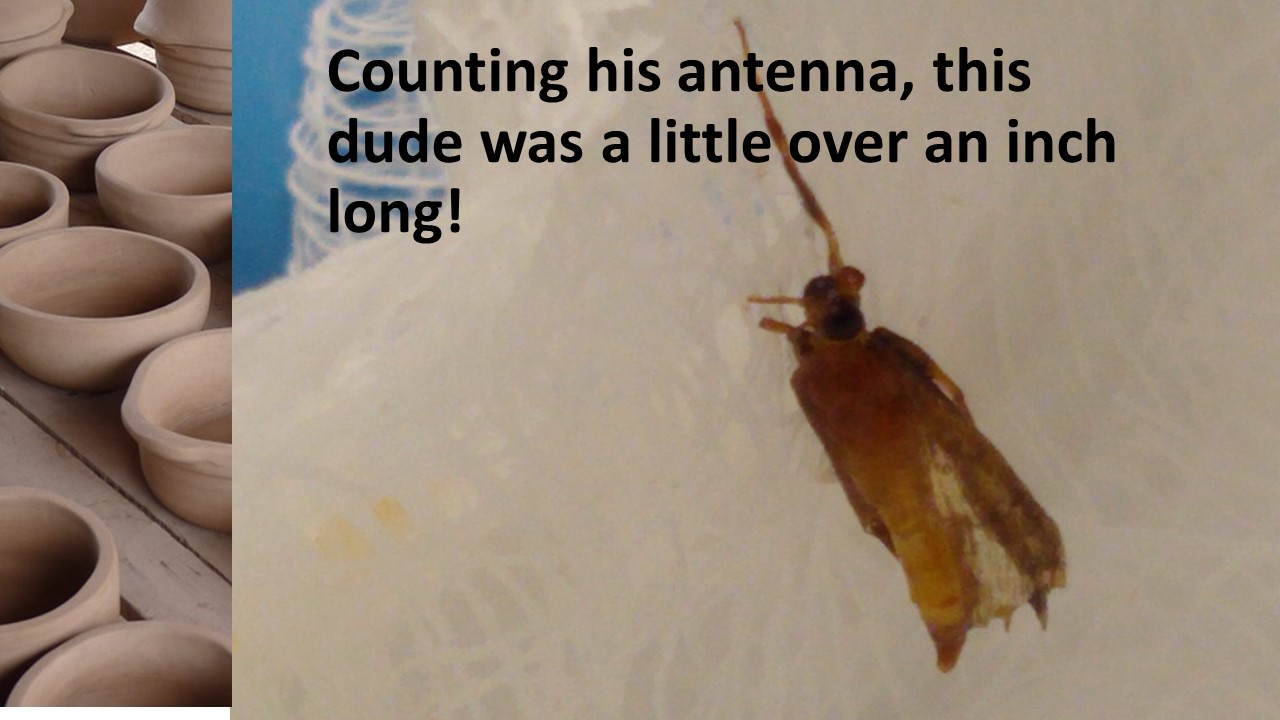

I’d ridden my bicycle down to the marina to meet with some friends late Friday. It was after dark when I left. With a rather bright LED light on my handlebars, I wasn’t worried. But about halfway home something flew into my right ear. The bug dug down deep and as it fluttered its wings. I stopped. I’d always thought the saying, “a bug in your ear,” was a metaphor. Now I was shaking my head and pounding it, in an attempt to free the bug. I was going insane. I rode on home and about every 15 seconds the insect would have saved enough energy to flutter again for a few seconds. Coming into the house, I called out that I needed help. Donna, after checking with the Mayo Clinic website, warmed up some oil and poured it into my ear. It was supposed to flush the bug out, but it never came out. Eventually the bug stopped fluttering. I assumed it drowned. Yesterday morning (which is why I wasn’t in Bible Study), I went to urgent care. They were able to remove the bug. It was a big bug and counting its antenna was over an inch long. That may not sound big until you consider the size of your ear canal.

I’d ridden my bicycle down to the marina to meet with some friends late Friday. It was after dark when I left. With a rather bright LED light on my handlebars, I wasn’t worried. But about halfway home something flew into my right ear. The bug dug down deep and as it fluttered its wings. I stopped. I’d always thought the saying, “a bug in your ear,” was a metaphor. Now I was shaking my head and pounding it, in an attempt to free the bug. I was going insane. I rode on home and about every 15 seconds the insect would have saved enough energy to flutter again for a few seconds. Coming into the house, I called out that I needed help. Donna, after checking with the Mayo Clinic website, warmed up some oil and poured it into my ear. It was supposed to flush the bug out, but it never came out. Eventually the bug stopped fluttering. I assumed it drowned. Yesterday morning (which is why I wasn’t in Bible Study), I went to urgent care. They were able to remove the bug. It was a big bug and counting its antenna was over an inch long. That may not sound big until you consider the size of your ear canal.

Professor James Cone, writing about the African American musical tradition, said that spirituals do not deny history. They don’t deny that there’s a lot wrong in our world. Instead, spirituals see history leading toward divine fulfillment.

Professor James Cone, writing about the African American musical tradition, said that spirituals do not deny history. They don’t deny that there’s a lot wrong in our world. Instead, spirituals see history leading toward divine fulfillment.

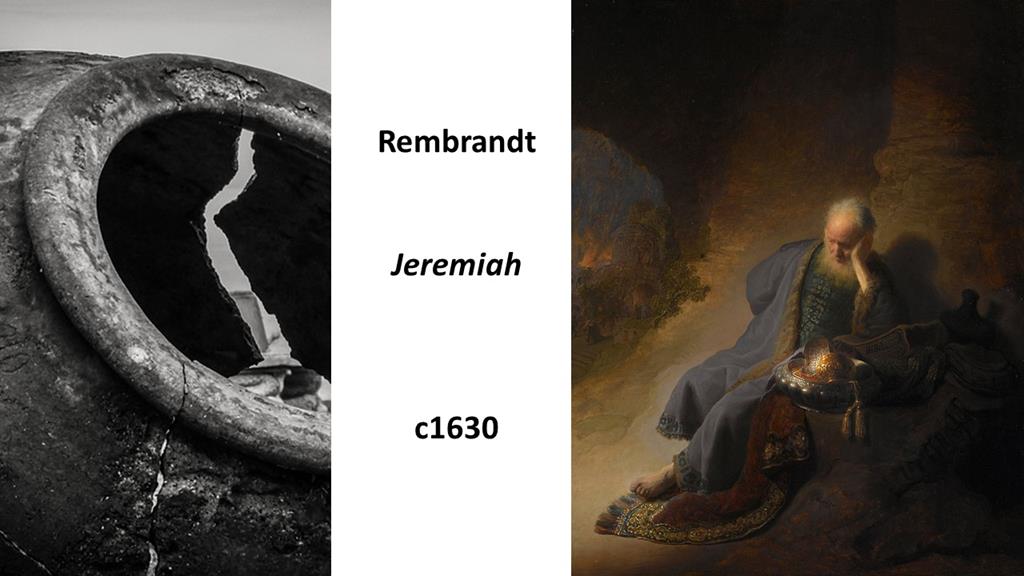

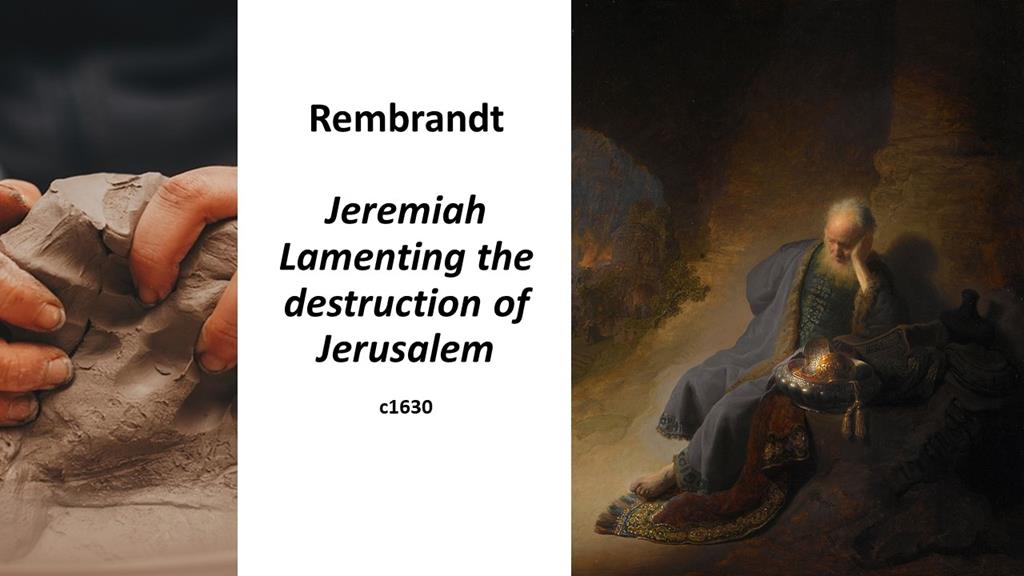

Let’s imagine ourselves in the 6th Century before the Common Era and join Jeremiah. Having left the city, the prophet walks alone, across what should be a grain field. With each step he kicks up dust. The immature stalks of grain, long dried under the desert sun, crunch under his feet. This should be the time of the harvest, but there are no men out swinging sickles nor women gathering sheaves. The grapes and the figs and the olives area also shrivel on the vine. The harvest has failed. There’s going to be hunger. And with Nebuchadnezzar’s army on the loose, there won’t be a chance to trade for food. Jeremiah’s heart is heavy. As he looks back toward the walls of the city, he cries. He images the bloated bellies of the young and the riots when there is no more bread in the market.

Let’s imagine ourselves in the 6th Century before the Common Era and join Jeremiah. Having left the city, the prophet walks alone, across what should be a grain field. With each step he kicks up dust. The immature stalks of grain, long dried under the desert sun, crunch under his feet. This should be the time of the harvest, but there are no men out swinging sickles nor women gathering sheaves. The grapes and the figs and the olives area also shrivel on the vine. The harvest has failed. There’s going to be hunger. And with Nebuchadnezzar’s army on the loose, there won’t be a chance to trade for food. Jeremiah’s heart is heavy. As he looks back toward the walls of the city, he cries. He images the bloated bellies of the young and the riots when there is no more bread in the market. “We are not saved.” What painful words. It’s tough being a prophet, bearing the burdens of a people. Yet, as he cries, he hears something. A voice? Can it be God’s voice? “I’m disappointed. Why have they provoked me to anger with their images and foreign idols?” Yes, it’s God, speaking judgment on the Hebrew people.

“We are not saved.” What painful words. It’s tough being a prophet, bearing the burdens of a people. Yet, as he cries, he hears something. A voice? Can it be God’s voice? “I’m disappointed. Why have they provoked me to anger with their images and foreign idols?” Yes, it’s God, speaking judgment on the Hebrew people.

Jesus told those in the synagogue in Nazareth that a prophet is never accepted in his hometown.

Jesus told those in the synagogue in Nazareth that a prophet is never accepted in his hometown. While Jeremiah was considered a traitor in his life, looking back we cannot help but to see that he was a true patriot. God’s people are not called to be loyal to a king or even to a nation. Our first loyalty always belongs to God and when we fail to put God first, we risk hardship, judgment, and perhaps even defeat. Do we have the faith and the perseverance of Jeremiah? Are their Jeremiahs in our society today? If so, do we listen? Or do we tune him or her out, or worse, mock and abuse?

While Jeremiah was considered a traitor in his life, looking back we cannot help but to see that he was a true patriot. God’s people are not called to be loyal to a king or even to a nation. Our first loyalty always belongs to God and when we fail to put God first, we risk hardship, judgment, and perhaps even defeat. Do we have the faith and the perseverance of Jeremiah? Are their Jeremiahs in our society today? If so, do we listen? Or do we tune him or her out, or worse, mock and abuse? You know, on the 22nd, we’re going to have our first community forum to discuss civility. If we want to build a better society, which is one of the goals of the church as we are to be a part of building God’s kingdom, we must listen to others. I hope you plan to attend and to tell others about the forum. Go to our church’s Facebook page and like the event and share it with others on your page. We have got to get our community and our nation on a new direction. We need to be about listening to all voices, even the voice of a Jeremiah, crying a fountain of tears. Only by listening to others who challenge us, like Jeremiah challenged Jerusalem, will we be able to build a better society.

You know, on the 22nd, we’re going to have our first community forum to discuss civility. If we want to build a better society, which is one of the goals of the church as we are to be a part of building God’s kingdom, we must listen to others. I hope you plan to attend and to tell others about the forum. Go to our church’s Facebook page and like the event and share it with others on your page. We have got to get our community and our nation on a new direction. We need to be about listening to all voices, even the voice of a Jeremiah, crying a fountain of tears. Only by listening to others who challenge us, like Jeremiah challenged Jerusalem, will we be able to build a better society. Let’s go back to that day, some 2500 years ago, and join Jeremiah once more… The heat of the day is over when Jeremiah starts back toward the city. Having wrestled with God through lament, Jeremiah is more assured than ever of God. Ahead, the city David claimed his capital, is magnificently lighted by the setting sun. As the even breeze picks up, Jeremiah picks up his pace.

Let’s go back to that day, some 2500 years ago, and join Jeremiah once more… The heat of the day is over when Jeremiah starts back toward the city. Having wrestled with God through lament, Jeremiah is more assured than ever of God. Ahead, the city David claimed his capital, is magnificently lighted by the setting sun. As the even breeze picks up, Jeremiah picks up his pace. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Beautiful pottery breaks. Today, during the sermon, hold on to the shard you’ve been given, and ponder God’s judgment. Think about what it means to be broken, unfixable. But don’t throw away the shard. When the service is over, take it over to Liston hall, where we’ll attempt to put it back together and see what kind of design Sue Jones created for us.

Beautiful pottery breaks. Today, during the sermon, hold on to the shard you’ve been given, and ponder God’s judgment. Think about what it means to be broken, unfixable. But don’t throw away the shard. When the service is over, take it over to Liston hall, where we’ll attempt to put it back together and see what kind of design Sue Jones created for us.

For the people of Jeremiah’s day, storm clouds are gathering. It’s not looking good. It’s kind of like that vision we get from the song “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” those wayward cowpokes who are eternally damned to chase the Devil’s herd. Storm clouds are always frightening. But let’s think about ourselves.

For the people of Jeremiah’s day, storm clouds are gathering. It’s not looking good. It’s kind of like that vision we get from the song “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” those wayward cowpokes who are eternally damned to chase the Devil’s herd. Storm clouds are always frightening. But let’s think about ourselves. You know, we have blessed as a nation in that no foreign army has invaded us for over 200 years. The last was during the War of 1812. It’s been a century and a half since those of us who are from the South experienced the horrors of having towns and cities burned, armies destroyed, and people suffering. We can only image what it was like for the people in Savannah during that Civil War, hearing the distant bombardments of Fort Pulaski and Fort MaAllister, and then, in 1864, the rumors building fear as Sherman’s army approaches.

You know, we have blessed as a nation in that no foreign army has invaded us for over 200 years. The last was during the War of 1812. It’s been a century and a half since those of us who are from the South experienced the horrors of having towns and cities burned, armies destroyed, and people suffering. We can only image what it was like for the people in Savannah during that Civil War, hearing the distant bombardments of Fort Pulaski and Fort MaAllister, and then, in 1864, the rumors building fear as Sherman’s army approaches. In this section of Jeremiah, the approaching Babylonian army is described as a hot wind blowing up a frightful dust cloud off the desert. This could be like the dust clouds off Africa that eventually turn into hurricanes that threaten our coastline. In the part I skipped, we hear how the rumors begin to filter down to Judah and Jerusalem, starting way to the north, above the Sea of Galilee, in the territories of Dan. We know a similar drill with hurricanes as they approach the Leeward Island and the Lesser Antilles and the Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Cuba, and the Bahamas as the storm makes its way across the South Atlantic. Sometimes these storms are like Jeremiah’s vision, bringing total destruction. Just as we hurt seeing the damage Dorian caused the Bahamas, we also worry what might happen to us if the storm doesn’t turn, Jeremiah is bothered by his vision. He can see it happening and cries out in anguish. But despite the heartache of what he sees, he faithfully proclaims God’s word.

In this section of Jeremiah, the approaching Babylonian army is described as a hot wind blowing up a frightful dust cloud off the desert. This could be like the dust clouds off Africa that eventually turn into hurricanes that threaten our coastline. In the part I skipped, we hear how the rumors begin to filter down to Judah and Jerusalem, starting way to the north, above the Sea of Galilee, in the territories of Dan. We know a similar drill with hurricanes as they approach the Leeward Island and the Lesser Antilles and the Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Cuba, and the Bahamas as the storm makes its way across the South Atlantic. Sometimes these storms are like Jeremiah’s vision, bringing total destruction. Just as we hurt seeing the damage Dorian caused the Bahamas, we also worry what might happen to us if the storm doesn’t turn, Jeremiah is bothered by his vision. He can see it happening and cries out in anguish. But despite the heartache of what he sees, he faithfully proclaims God’s word. The second part of my reading describes the aftermath. Destruction is total. Starting with verse 23, the poem recalls the “dismantling of creation.”

The second part of my reading describes the aftermath. Destruction is total. Starting with verse 23, the poem recalls the “dismantling of creation.” For Christians living in America, we may have a hard time relating to Jeremiah’s vision. But many Christians, those living around the globe in places where it’s dangerous to worship Jesus, recognize Jeremiah’s anguish as their own. For them, gathered around this table on World Communion Sunday, they are in danger. They know what it means to worship in fear, to experience the loss of jobs, of their homes and their land because of their faith. They know what it means to be locked up, to be tortured, and to watch loved ones be taken away and never return because of their faith. Christians are suffering in China, in Eritrea, in North Korea, in Iran and Iraq, in Syria and parts of India. We must stand by those who do not enjoy the freedom to worship as we enjoy it.

For Christians living in America, we may have a hard time relating to Jeremiah’s vision. But many Christians, those living around the globe in places where it’s dangerous to worship Jesus, recognize Jeremiah’s anguish as their own. For them, gathered around this table on World Communion Sunday, they are in danger. They know what it means to worship in fear, to experience the loss of jobs, of their homes and their land because of their faith. They know what it means to be locked up, to be tortured, and to watch loved ones be taken away and never return because of their faith. Christians are suffering in China, in Eritrea, in North Korea, in Iran and Iraq, in Syria and parts of India. We must stand by those who do not enjoy the freedom to worship as we enjoy it. Remember, we have an insight Jeremiah didn’t have. We know about the resurrection, how the grave is not the end. Jeremiah knew that somehow God’s destruction wasn’t going to quite be total. We know that even if it appears total, as it does at death, as when we peer down into the grave, God is still God and the end is not the end.

Remember, we have an insight Jeremiah didn’t have. We know about the resurrection, how the grave is not the end. Jeremiah knew that somehow God’s destruction wasn’t going to quite be total. We know that even if it appears total, as it does at death, as when we peer down into the grave, God is still God and the end is not the end. The center of the gospel is the hope we have in the resurrection to eternal life. And for that reason, we can face those storm clouds. We can face the stampede of Satan’s herd and the cowboys running roughshod across the skies, and know that as bad as things are, there’s hope. We may feel like we’re just broken shards of pottery, but God has the power to make what’s broken new and whole. Believe in God. Hold on to such hope. Amen.

The center of the gospel is the hope we have in the resurrection to eternal life. And for that reason, we can face those storm clouds. We can face the stampede of Satan’s herd and the cowboys running roughshod across the skies, and know that as bad as things are, there’s hope. We may feel like we’re just broken shards of pottery, but God has the power to make what’s broken new and whole. Believe in God. Hold on to such hope. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison You might be wondering about all this emphasis on pottery as we look at the Prophet Jeremiah. Pottery was a revolutionary technology in the ancient world. It allowed more movement as people could store things in pots, such as water and grain.

You might be wondering about all this emphasis on pottery as we look at the Prophet Jeremiah. Pottery was a revolutionary technology in the ancient world. It allowed more movement as people could store things in pots, such as water and grain.

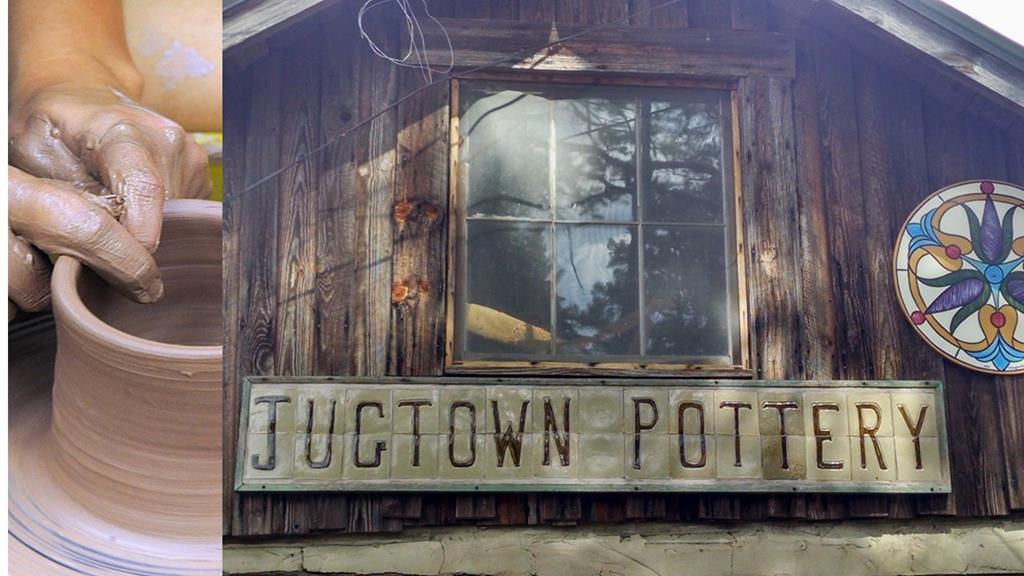

About twenty-five miles northwest of where I was born, where the Carolina Sandhills turn into clay hills, is a dot on the map known as Jugtown. It’s a place I like to visit when I am back in that part of the world. Today, the area around Jugtown and Seagrove is dotted with crafty potters who turn muck into beautiful and useful art. It’s a treat, as we’ve just seen on the video, to watch a potter turn a lump of clay on the wheel into something useful and beautiful.

About twenty-five miles northwest of where I was born, where the Carolina Sandhills turn into clay hills, is a dot on the map known as Jugtown. It’s a place I like to visit when I am back in that part of the world. Today, the area around Jugtown and Seagrove is dotted with crafty potters who turn muck into beautiful and useful art. It’s a treat, as we’ve just seen on the video, to watch a potter turn a lump of clay on the wheel into something useful and beautiful. Jugtown received its name, as you can guess, from jugs. The law-abiding folks in the clay hills around there, I’m sure, intended their jugs to store molasses, honey, cane syrup, or something similar. Of course, it was also used to hold liquefied corn (also known as white lightning or moonshine). But with the advent of mason jars, such use of the jugs ceased. But early on, some of the potters had new ideas. In 1917, two of the potters began selling their wares in a store and tea shop in New York City. They emphasized utilitarian pots, things that could be used such as pie plates, crocks, mugs, and bowls. They stamped their unique mark on the bottom of each vessel. Over time, they began to teach new potters the craft and as one generation passed, another took up the wheel. Today, if you go to the area around Jugtown, you’ll find dozens or potters selling their wares. These artists have brought new life into that worthless clay that sticks to your shoes and gums up a plow.

Jugtown received its name, as you can guess, from jugs. The law-abiding folks in the clay hills around there, I’m sure, intended their jugs to store molasses, honey, cane syrup, or something similar. Of course, it was also used to hold liquefied corn (also known as white lightning or moonshine). But with the advent of mason jars, such use of the jugs ceased. But early on, some of the potters had new ideas. In 1917, two of the potters began selling their wares in a store and tea shop in New York City. They emphasized utilitarian pots, things that could be used such as pie plates, crocks, mugs, and bowls. They stamped their unique mark on the bottom of each vessel. Over time, they began to teach new potters the craft and as one generation passed, another took up the wheel. Today, if you go to the area around Jugtown, you’ll find dozens or potters selling their wares. These artists have brought new life into that worthless clay that sticks to your shoes and gums up a plow. Jeremiah is called to the potter’s house where God uses a common image of the ancient world to make a profound message. God’s word comes to him as he watches the potter over and over start off one direction with clay, and it not working, so he reworks the clay into something more suitable. This sounds hopeful. God will continue to work with us until we become a vessel that serves some purpose. One preacher, writing about this text, said that it demonstrates a sovereign God, “not a God of absolute capricious control, but a gracious willingness to change his plan to benefit his flawed people. When God discovers this fatal flaw in his people, he does not simply destroy them; he offers to start over.”

Jeremiah is called to the potter’s house where God uses a common image of the ancient world to make a profound message. God’s word comes to him as he watches the potter over and over start off one direction with clay, and it not working, so he reworks the clay into something more suitable. This sounds hopeful. God will continue to work with us until we become a vessel that serves some purpose. One preacher, writing about this text, said that it demonstrates a sovereign God, “not a God of absolute capricious control, but a gracious willingness to change his plan to benefit his flawed people. When God discovers this fatal flaw in his people, he does not simply destroy them; he offers to start over.”  Jeremiah’s task is to preach impending judgment to God’s people. If they don’t shape up, if they don’t stop running around chasing foreign gods and idols, if they act like they’re in control and the God of the Universe is of no matter, they will be punished. Just as the potter can shape a vessel in a new way, they can be handled in a different manner. God can shape another nation to punish. There appears to still time, at this point, for the Hebrew people to change. Later prophecies of Jeremiah hold out no hope of repentance, but here, it’s not too late.

Jeremiah’s task is to preach impending judgment to God’s people. If they don’t shape up, if they don’t stop running around chasing foreign gods and idols, if they act like they’re in control and the God of the Universe is of no matter, they will be punished. Just as the potter can shape a vessel in a new way, they can be handled in a different manner. God can shape another nation to punish. There appears to still time, at this point, for the Hebrew people to change. Later prophecies of Jeremiah hold out no hope of repentance, but here, it’s not too late. The message of this passage is that God has the power to reshape us, but we must let God work with us. If we resist God’s shaping, we may not be completely crushed, but we won’t fulfill the potential for which we were designed. The intention of our passage isn’t to be fatalistic and say we have no control. Instead, it’s a warning that we’re to work with God and not against him.

The message of this passage is that God has the power to reshape us, but we must let God work with us. If we resist God’s shaping, we may not be completely crushed, but we won’t fulfill the potential for which we were designed. The intention of our passage isn’t to be fatalistic and say we have no control. Instead, it’s a warning that we’re to work with God and not against him. When you leave this sanctuary today, ponder these questions: Where is God at work in the world? How can we participate? How can we be the clay that trusts the potter? Amen.

When you leave this sanctuary today, ponder these questions: Where is God at work in the world? How can we participate? How can we be the clay that trusts the potter? Amen.

Last week we learned of Jeremiah’s call by God as a prophet to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant.”

Last week we learned of Jeremiah’s call by God as a prophet to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant.”

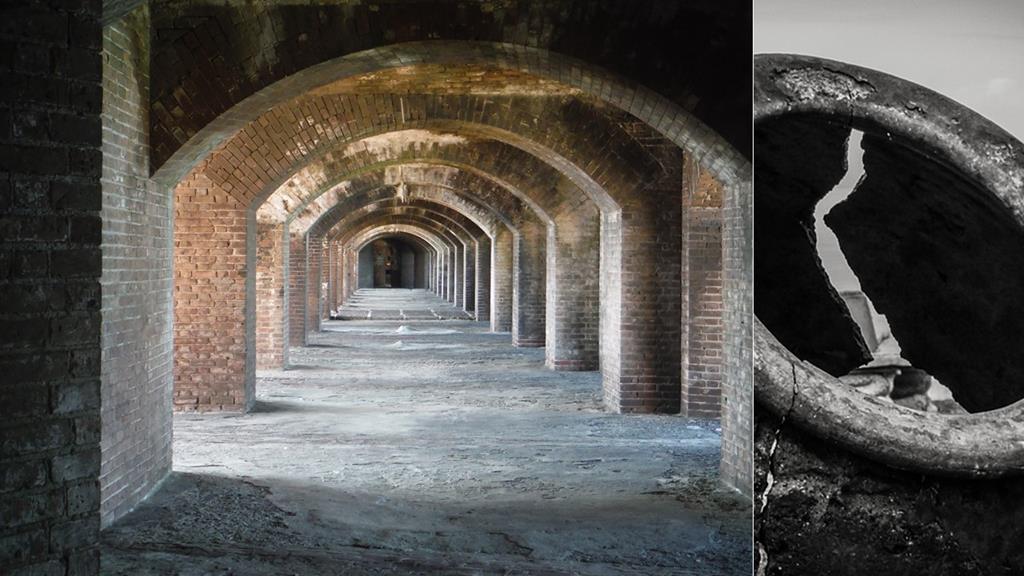

In the spring of 2018, my sister, my father, and I took a trip to the Dry Tortugas. I’m sure many of you read the article I had about the trip in The Skinnie.

In the spring of 2018, my sister, my father, and I took a trip to the Dry Tortugas. I’m sure many of you read the article I had about the trip in The Skinnie. If you’re going to have a fort with a substantial garrison on an island without fresh water, you must find a way to overcome that limitation. The engineers who designed Fort Jefferson came up with a unique way to address the lack of water. They built a series of cisterns under the walls of the fort and designed a system to funnel rainwater into the cisterns where they provided water for later use. The fort could hold nearly two million gallons of water. It was thought there would be enough water and provisions within the walls for the fort to survive a yearlong siege.

If you’re going to have a fort with a substantial garrison on an island without fresh water, you must find a way to overcome that limitation. The engineers who designed Fort Jefferson came up with a unique way to address the lack of water. They built a series of cisterns under the walls of the fort and designed a system to funnel rainwater into the cisterns where they provided water for later use. The fort could hold nearly two million gallons of water. It was thought there would be enough water and provisions within the walls for the fort to survive a yearlong siege. But the plans of men and women often fail. This massive fort, built with millions of bricks and packed dirt, was so heavy that of the 136 cisterns, all but three cracked and allowed saltwater to infiltrate. They became useless.

But the plans of men and women often fail. This massive fort, built with millions of bricks and packed dirt, was so heavy that of the 136 cisterns, all but three cracked and allowed saltwater to infiltrate. They became useless. The cracked cistern image shows Israel’s condition after chasing after non-existent gods. As humans, we all need water. An image of God’s providence found throughout Scripture is that of living water nourishing us.

The cracked cistern image shows Israel’s condition after chasing after non-existent gods. As humans, we all need water. An image of God’s providence found throughout Scripture is that of living water nourishing us.

Friends, we don’t want to be cracked pots. We want to be vessels holding abundant living water that will quench our thirst, and can be shared to others, to quench theirs. Amen.

Friends, we don’t want to be cracked pots. We want to be vessels holding abundant living water that will quench our thirst, and can be shared to others, to quench theirs. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison The prophet Jeremiah lived in interesting times. He was one of the longest serving prophets in Israel’s history, his calling coming as the Assyrians were losing power. It was a time of optimism in Jerusalem because they had existed as a vassal state under Assyria for over a century. It appeared they might be free once again, as in the years of Kings David and Solomon. Furthermore, Josiah, one of Judah’s few good kings, was implementing religious reforms. But then Josiah is killed in battle against Egypt.

The prophet Jeremiah lived in interesting times. He was one of the longest serving prophets in Israel’s history, his calling coming as the Assyrians were losing power. It was a time of optimism in Jerusalem because they had existed as a vassal state under Assyria for over a century. It appeared they might be free once again, as in the years of Kings David and Solomon. Furthermore, Josiah, one of Judah’s few good kings, was implementing religious reforms. But then Josiah is killed in battle against Egypt. We, too, are living in interesting times. Things are scary in our world: rogue nations having the bomb, individuals going berserk and killing people, terrorists creating political instability, and huge storms leaving behind chaos and destruction. The news often leaves us fearful and angry. And since we often don’t have answers for the problems we face, we blame others. Ben Sasse, a Senator from Nebraska, suggests one of the few things uniting us is our contempt for those of whom we assign blame. “At least,” we say, “we’re not like them.”

We, too, are living in interesting times. Things are scary in our world: rogue nations having the bomb, individuals going berserk and killing people, terrorists creating political instability, and huge storms leaving behind chaos and destruction. The news often leaves us fearful and angry. And since we often don’t have answers for the problems we face, we blame others. Ben Sasse, a Senator from Nebraska, suggests one of the few things uniting us is our contempt for those of whom we assign blame. “At least,” we say, “we’re not like them.”

Jeremiah was a bullfrog,

Jeremiah was a bullfrog, Back in early May, Gary Witbeck and I took a trip into the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. On our second night, we were camping on a platform at a place called “Big Water.” It’s the headwaters for the Suwanee River. As the sun set and evening descended, we watched alligators battle over territory (or maybe they were fighting over mates, or were flirting, we couldn’t tell the difference). While the gators fought, in the background a chorus of frogs sang. Their song would come in waves, starting up the river and working its way down and then back up. The frogs were in perfect harmony. You couldn’t tell one frog’s croak from another. It was quite beautiful.

Back in early May, Gary Witbeck and I took a trip into the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. On our second night, we were camping on a platform at a place called “Big Water.” It’s the headwaters for the Suwanee River. As the sun set and evening descended, we watched alligators battle over territory (or maybe they were fighting over mates, or were flirting, we couldn’t tell the difference). While the gators fought, in the background a chorus of frogs sang. Their song would come in waves, starting up the river and working its way down and then back up. The frogs were in perfect harmony. You couldn’t tell one frog’s croak from another. It was quite beautiful. But this is where the song gets it wrong. The one singing, claims to be a friend of Jeremiah, enjoying drinking his wine. But the Jeremiah of the Old Testament, was often lonely. He didn’t have many friends bellying up to him at the bar. Like a bullfrog, he cried out the message from God that he’s been given, and message that no one wanted to hear, so he was often alone and vulnerable. But he was faithful, and when we consider eternity, that makes all the difference in the world.

But this is where the song gets it wrong. The one singing, claims to be a friend of Jeremiah, enjoying drinking his wine. But the Jeremiah of the Old Testament, was often lonely. He didn’t have many friends bellying up to him at the bar. Like a bullfrog, he cried out the message from God that he’s been given, and message that no one wanted to hear, so he was often alone and vulnerable. But he was faithful, and when we consider eternity, that makes all the difference in the world. You’ll notice in the text that Jeremiah didn’t have a choice in all this. He was chosen by God before the foundation of the earth. Yesterday morning, in the Men’s Bible Study, we were reading Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, where are reminded that God calls us through Jesus Christ to do the work which has been prepared for us.

You’ll notice in the text that Jeremiah didn’t have a choice in all this. He was chosen by God before the foundation of the earth. Yesterday morning, in the Men’s Bible Study, we were reading Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, where are reminded that God calls us through Jesus Christ to do the work which has been prepared for us. Of course, like Jeremiah, we can beg off. Jeremiah said, “I’m just a boy.” Looking around, we might say, “we’re too old.” But God has heard that one, too. Remember Abraham and Sara? How old were they?

Of course, like Jeremiah, we can beg off. Jeremiah said, “I’m just a boy.” Looking around, we might say, “we’re too old.” But God has heard that one, too. Remember Abraham and Sara? How old were they? Jeremiah has been appointed for a mission. Likewise, the church has been appointed for a mission. We’re all called by God to follow Jesus and to point to him as our hope in a world that often seems hopeless.

Jeremiah has been appointed for a mission. Likewise, the church has been appointed for a mission. We’re all called by God to follow Jesus and to point to him as our hope in a world that often seems hopeless. Over the next six weeks, as we work through this series, we’ll be using images of potters. Our image today is a clump of clay, being kneaded like bread dough. The technical term for doing this to clay is “wedged.” The potter takes the clay and stretches and pushes it like a baker works dough. In doing this, all the air pockets are worked out so that the clay is easier to shape on the wheel and afterwards, when firing, the pot won’t have air pockets that’ll explode and destroy the vessel.

Over the next six weeks, as we work through this series, we’ll be using images of potters. Our image today is a clump of clay, being kneaded like bread dough. The technical term for doing this to clay is “wedged.” The potter takes the clay and stretches and pushes it like a baker works dough. In doing this, all the air pockets are worked out so that the clay is easier to shape on the wheel and afterwards, when firing, the pot won’t have air pockets that’ll explode and destroy the vessel. Paul, writing to the Ephesians, encouraged them to put away all bitterness, wrath, anger, wrangling, slander and malice. Such behavior is to be wedged out of us, like air is wedged out of the clay, so that we might be kind to one another, tenderhearted, and forgiving.

Paul, writing to the Ephesians, encouraged them to put away all bitterness, wrath, anger, wrangling, slander and malice. Such behavior is to be wedged out of us, like air is wedged out of the clay, so that we might be kind to one another, tenderhearted, and forgiving.