Much of this blog post had been originally published as an article in The Skinnie published in March 2018. This version has been slightly edited and altered.

Easter Sunday 1982, Old Salem, North Carolina

The wake-up call came at 4:30 AM Sunday morning. I am staying at a hotel right across from Old Salem in present-day Winston Salem. Washing the sleep out of my eyes, I hear the music playing from the street down below. It was been warm when I left home in eastern North Carolina, but a cold snap descended on Saturday. I dress as warmly as possible, pulling on multiple layers. I realize I don’t even have gloves with me.

By 5 AM, I am outside the hotel, walking with strangers, heading to Home Moravian Church. On most street corners, we pass brass quartets playing Easter music, calling people to come. By the time I reached the church, thousands had gathered, waiting in front of the steps of the sanctuary. A cold wind blows and the dark sky spits snow. In the distance, we hear the brass playing. We shuffle around trying to stay warm and waited. The anticipation of the crowd is high as we have all gathered to participate in the second oldest Easter sunrise service in North America. The honor for the oldest sunrise tradition belongs to the Moravians of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, who began holding such services in 1754.

It was still dark when a light comes on inside the church foyer. Then massive wooden doors fly open. The pastor steps out on to the porch. He raises his arms and shouts, “Christ is Risen!” We respond, “He is Risen Indeed!” The Pastor and his assistants step out of the church, and we follow them down Church Street to God’s Acre, the community’s cemetery. God’s Acre is many acres, large enough to hold the thousands who have gathered. We pack in and wait as the sky becomes lighter gray. A few stray flakes of snow still fall.

Then it starts. All those brass quartets unite, and they march in from behind us playing Easter hymns. As they move to the front, we stand and began to sing. The ministers pray and read scripture. The pastor offers a brief message about the hope of the resurrection. Somewhere behind the gray clouds, the sun rises. A new day begins. The benediction is pronounced and we head our separate ways.

Arriving back in the hotel, I stop by the restaurant for breakfast. The place is packed with those coming back from the service. The poor lone waitress is running around trying to serve everyone. Most of us just want hot coffee and are willing to wait to eat as we warm up. She apologizes and says the management had forgotten that it’s Easter Sunday and hadn’t scheduled anyone else to work the shift. Several of us help out, taking turns making and serving coffee as she takes and delivers our orders.

History of the Sunrise Service

The Moravians of Old Salem have been celebrating Easter Sunrise at God’s Acre since 1772, picking up on a practice that begin in Europe in 1732. In the town of Hernhut, which is now in the Czech Republic, the young men of the church gathered in the cemetery during the night and waited for dawn by singing hymns of the faith. The services are simple with hymns, prayers, scripture, and a brief message that is all done to the glory of God. The sunrise service is now an established tradition within the Moravian Church and one that has been adopted by many other Christian denominations.

Of course, those Moravian young men were not the first to be up at sunrise on Easter. That distinction goes to the women described in the gospels who headed out before sunrise to anoint Jesus body before the tomb was sealed. They were shocked to find the grave open and Jesus’ body missing. As the events of that day unfold, they learn of his resurrection, an event that gives hope to Christians to this day.

Easter Sunday, 1975, Wilmington, North Carolina

I first attended an Easter sunrise service as a high school student. It was held in a cemetery off Greenville Sound, east of Wilmington, North Carolina. Unlike the year I was at Old Salem, the skies were clear. And just as the sun broke over the horizon, its rays reflecting off the water and bring warmth to the marsh grass, several ducks took the skies, their calls and the flapping of their wings drowning out the voice of the preacher. Even they celebrated the new day. In the years before seminary, I would attend many such services at a variety of locations. The message was always the same. Christ has risen!

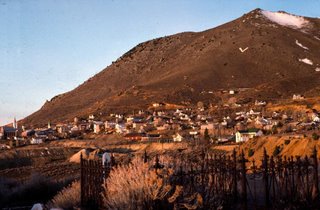

Easter Sunday 1989, Virginia City, Nevada

For obvious reasons, sunrise services seem to be more popular in the American South, but as a seminary student pastor, I brought the tradition to Virginia City, Nevada. There, we gathered on “Boot Hill” on a cold morning. The temperature was in the mid-20s and the wind was blowing hard over Sun Mountain. But we witnessed a glorious sunrise, the rays racing up Six Mile Canyon. Afterwards, we enjoyed coffee and warm pastries back at the church.

Easter Sunday 1991, Ellicottville, New York

In my first call to a church in Ellicottville, New York, a community known for skiing, we partnered with Holiday Valley, the local ski resort, to host the service on a deck outside a clubhouse. It was even colder than at Virginia City, but we dressed appropriately, wearing ski bids and parkers. Nicky, a young woman volunteered to provide music on a keyboard. We started with a song and were going to close with the traditional hymn, “Christ the Lord is Risen Today.” As we began to sing, Nicky missed note after note. I looked over to see what was wrong. The keyboard had frosted over between hymns and her fingers were sticking to the keys. Afterwards, with hot drinks and donuts inside the lodge, we had a laugh over the situation. The next year, she brought a blanket to lay over the keyboard.

Easter Sunday 2020, Skidaway Island, Georgia

When I accepted the called to the Presbyterian Church on Skidaway Island, I saw the perfect opportunity to hold an Easter Sunrise Service in a park next to the marina on the north end of the Island. Starting in 2015, we began holding services. The first year, we had maybe 50 in attendance. It was beautiful as the sun rose over the marsh and the Wilmington River.

In 2016, a heavy rainstorm was ensuing, so about 30 who came out made their way to the church’s fellowship hall where held the service. Afterwards, Thom, a member of the church volunteered to video tape a sunrise in which we could use inside just in case of rain. Over the next several years, we had beautiful weather and our number grew to nearly 200 worshippers.

Then, in 2020, everything shut down because of COVID. The park had been closed and churches were not meeting inside. We decided to to record a sunrise service that involved just a few of us, all maintaining safe distance. After a live stream Maundy Thursday Service (which only had a camera operator, my associate, the organist, a soloist, and myself), we set up a green screen in the sanctuary to record. While the organist played in the background, we all did our parts, stepping in front of the green screen to be recorded. This allowed Thom’s sunrise to play behind us and it appeared as if we were at the marina.

The most precious moment in the service came when Gene, the soloist, sang “Jesus Christ, is Risen Today.” On the tape, the sun rose as birds took to air. A seagull, on the tape, flew toward the camera then turned back and flew out over the water. On the recording, this bird appeared to fly right through Gene’s head. We laughed and laughed and decided not to cut it out. “That alone is worth the price of admission,” Gene said.

We uploaded the sunrise service to YouTube and set it to go live on Easter Sunday morning. That Easter, we all slept in.

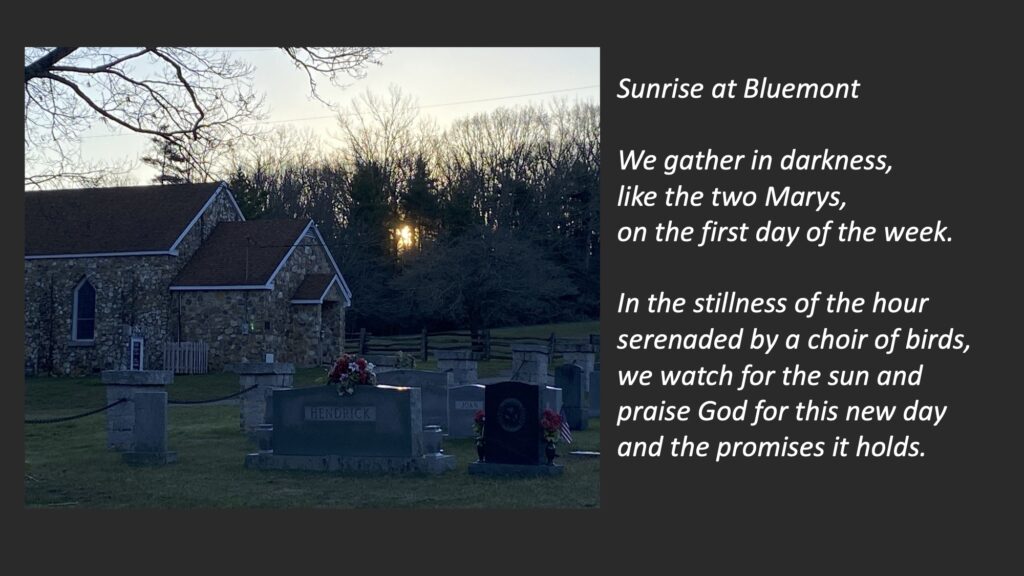

Sunrise 2022, Bluemont Church

Blue Ridge Parkway Milepost #192

This year, there will be a sunrise service at Bluemont Presbyterian Church, located along the parkway at milepost #191. The service is outside so you may want to bring a lawn chair and a blanket. The service will begin at 6:45 AM. Afterwards, coffee and a light breakfast will be hosted in the fellowship hall. We hope you will join us.

Other Holy Week Services along the Blue Ridge Parkway

Blue Ridge Parkway Milepost #180

April 14 Maundy Thursday communion

Mayberry Church at 6 PM

April 15 Good Friday Service

Bluemont Church at noon

April 17 Worship at Mayberry at 9 AM

Worship at Bluemont at 10:30 AM