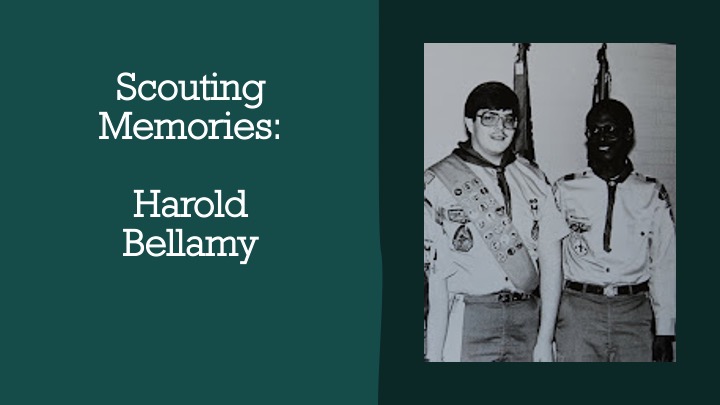

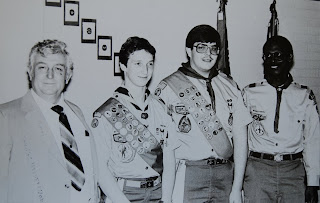

Last week, I introduced you to Delano. Today, I’m introducing you to Harold, an unlikely Scoutmaster from Tabor City during my time working for the Boy Scouts in Columbus and Bladen County, North Carolina in the early 1980s.

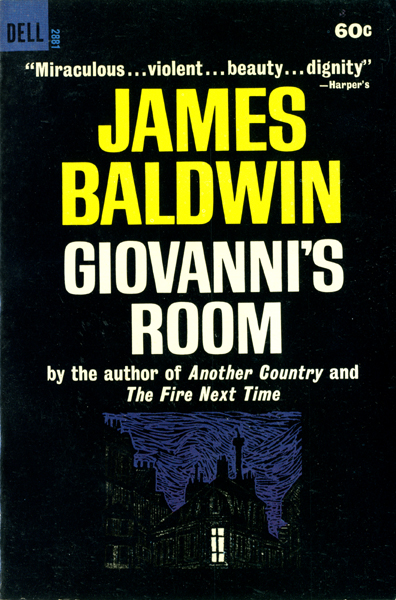

It was probably a cruel joke. Harold volunteered to spend a week with his scout troop at Camp Bowers. He asked me for book recommendations. I lent him a couple of books, one of which was James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. I knew he’d read it. It shocked him to learn of a book by Baldwin he hadn’t read. After all, he taught social studies. Furthermore, like Baldwin, he was an African American, both products of the Black Pentecostal church. And I was a white boy and the Boy Scout’s hired hand.

Giovanni’s Room isn’t your typical Baldwin book. Unlike Baldwin’s better-known writings, Giovanni’s Room has nothing to do with the African American experience. Set in Paris, the story features a unique triangle relationship between an American couple and an Italian (Giovanni). But it’s not the American girl, who’s interested in Giovanni; it’s David, the boy. I read the book in college. I found the book eye-opening and unnerving. Baldwin draws on his readers emotions by making them feel affection for all the characters. And he doesn’t touch on race. In addition to bisexuality, the story also involves capital punishment. After a fight with his former employer at a bar, Giovanni kills the man. The book ends with Giovanni’s execution for the murder.

When I lent him the book, I had a suspicion Harold was unaware of Baldwin’s sexuality. I should add that in addition to teaching Junior High, Harold was also a preacher in an Apostolic Pentecostal Church. But he dug right into the book.

Harold didn’t exactly fit the Norman Rockwell’s view of a scoutmaster. He ended up with the job by default. A coach at the high school had been recruited to be the scoutmaster. He asked Harold to be his assistant. That next school year, the coach accepted a high school position in South Carolina. When no one else stepped forward, Harold who wanted his troop to do well, took over as Scoutmaster. I don’t think Harold had ever camped before becoming an assistant scoutmaster. I’m not even sure he’d built a campfire and I’m pretty sure he never used a compass. Harold was much more comfortable sitting inside with his head in a book than outside swatting mosquitoes and gnats.

Even though Harold wasn’t created out of the scoutmaster’s mold, Harold was a great leader. Under his leadership, several of the boys in his troop earned their Eagle. These were the first Eagles earned in Tabor City in more than a decade. In fact, there had not been a troop in Tabor City for a decade before Harold and the coach got together. Harold served as Scoutmaster for four or five years.

Tabor City had been a rough place. While the Chamber of Commerce crowned the town the “Sweet Potato Capital of the World;” informally it was known as Razor City. The city had a brutal past. In the 1950s, the Klan ruled. An intervention by the FBI destroyed the Klan. However, an uneasy truce existed. As an African American, Harold helped break down barriers which existed into the early 80s. He earned respected from the community, as shown by families allowing their white sons to join his troop. Several of the business leaders of the community thanked me for working with Harold and wanted him to succeed.

Harold and I became friends, partly drawn together by our interest in history, social studies, literature and practical jokes. Later, as I felt drawn to seminary and to the ministry, we had some serious theological conversations. While I knew Harold to be a preacher at a Pentecostal Church in Tabor City, I just learned (see below) he ordained as a Bishop.

Harold finally forgave me for shattering his idyllic view of Baldwin. When my personal life became chaotic, Harold supported me. He even tried to set me up with another teacher at his school. I no longer remember her name, but husband had died in a work accident. We went out to lunch and her former mother-in-law was there. When we finished, we discovered that she’d paid for our meals! Harold, I think to care for both of us, attempted to bring us together. Later, after I left the area and moved across state, Harold and I occasionally met for lunch or dinner when I drove across state to see my parents in Wilmington. We wrote back and forth a few times after I left North Carolina for seminary in Pittsburgh, but with me having no reason to travel through Columbus County, and Harold no reason to head up north, we lost contact.

A few years ago, as I was again occasionally driving through Columbus County (from Savannah to Wilmington), I tried to find him. I learned he retired from teaching after serving as a principal in Chadbourn. In preparation for posting this, I learned of his death. Reading the comments posted on his obituary, I learned that after teaching in Tabor City, he taught at West Columbus High School and, as I had learned earlier, served as principal at Chadbourn Elementary. The secretary at the school could give me no more information about him. I also learned he become a Bishop. He suffered from a long-term illness and died in a Whiteville Nursing Home. He was 71 years old.

Yet the key to my salvation, which cannot save my body, is hidden in my flesh.

-David imagining Giovanni’s execution in James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room)