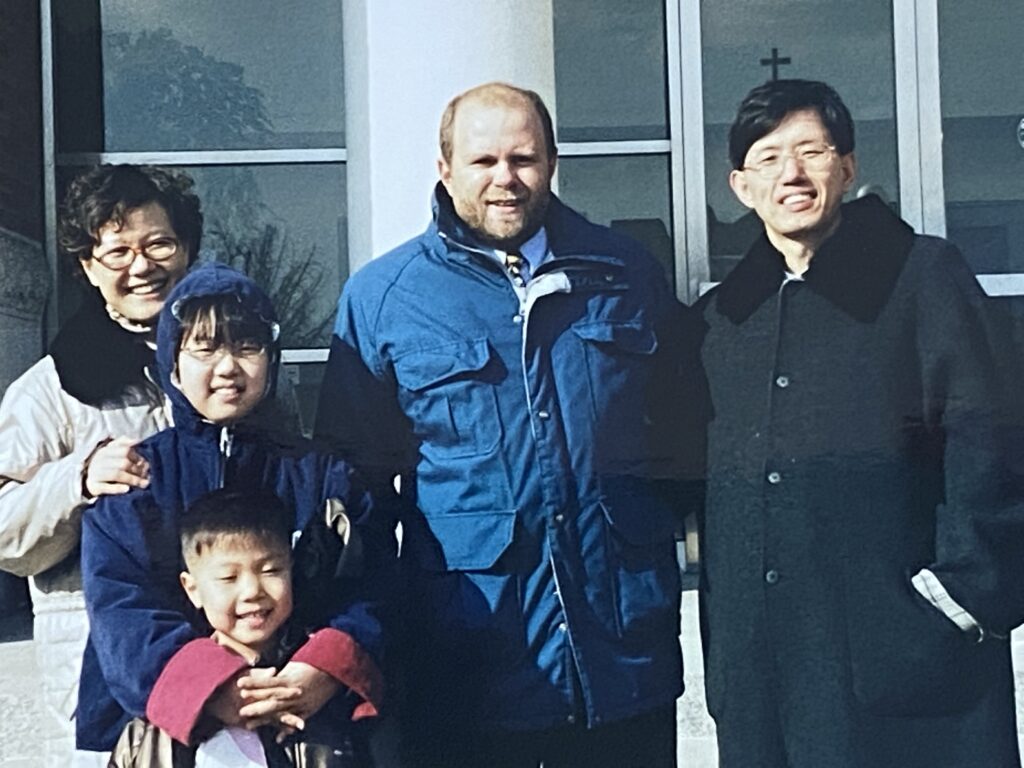

Last week, I wrote about my last day in Korea. This week, I’m resurrecting another story about that wonderful trip. I had taken a bus from Seoul to Wonju early on Sunday morning. Seung Hwan met me at the bus station. I preached to his congregation at the medical college in Wonju, then we spent the afternoon with a number of clergy in the area. One, I remember, was much older than us and had fled from the north before the Korean War. That evening I stayed in a retreat center east of Wonju.

Monday morning, 4 AM

The sounds of the bell tolling down off the mountainside wake me. I turn on my flashlight. It’s 4 A.M. For a few moments, I lay on my back, the warmth of the floor soothing my body. Seung Hwan had told me the floor would stay warm throughout the night. I had my doubts, but it’s still warm even though when I sit up, the air above me is quite chilly. The caretaker had built a small fire with just a half dozen pieces of split wood in the hearth under the flooring late yesterday afternoon. And now, 12 hours later, long after the coals have died out, the floor retains the heat.

I pull on socks and my pants and thrown on a coat. Stepping out of the sleeping room, I slide on my boots in the bathroom. I don’t lace them up. While I don’t plan to be gone long, I want to be outdoors. The air is cold. My breath, when I exhale, appears as smoke. I walk over to a ledge in front the lodge, hoping my movement will ward off the chill. In the distance I hear a train making its way through the valley. Wonju lies to the west, still sleeping. The sky is clear, the rain and snow of the day before has moved out.

Orion stands, perched high above Wonju, just above the western horizon. I make out several other winter constellations setting in the west before I turn and look toward where the sound from where the bell tolled. The mountain is dark; it’s a couple of hours to dawn. I imagine the priest at the temple, in the cold darkness of morning, getting up daily for their prayers. I, on the other hand, am ready to get back in my warm bed. Sleeping on the floor has never been this good. My bed is on the floor, on top of a rice matt and between two thick quilts. I crawl in. It’s still warm. Immediately, I fall back asleep, only to awake when the sun pierces through a small window.

In Wonju, Korea

I am on a two-week trip through South Korea. Yesterday, I had preached in Seung Hwan’s church at the Medical College.

He’d arranged for me to stay in this retreat lodge located just out of town, up in the foothills of the mountains. He’d given me the option of staying in a western hotel or traditional style lodging. I chose the traditional.

There are only a few others staying here, and none of them seems to speak English. We’re each assigned our own quarters consisting of a small bathroom with a toilet and sink attached a raised sleeping room. There are showers in the main lodge. There are no beds. The raised room has low ceilings, barely six feet high. The walls are mud. The floor is also mud with, I presume, slate or some kind of rock underneath. In the front of each sleeping chamber is a hearth. The fire in this hearth, which runs under the sleeping room, heats the floor. Once warm, the floor maintains its heat through the night.

Catching a bit of the Superbowl

Seung Hwan arrives shortly after daybreak. We have breakfast. It’s Monday morning and as we eat, we catch a bit of the Superbowl being played back in the States. St. Louis is playing Tennessee at the Georgia Dome. I try to explain the game to him. When it is over, we head out. We have a long climb ahead in Ch’iaksan National Park. We drive to the south end of the park, leave the car behind. Our packs contain heavy coats and crampons.

The Climb

We begin our climb on a dirt two track road. While the cities have modernized, rural Korea doesn’t appear to have changed much in centuries. We pass several small farms. Chickens run loose and dogs are penned behind the homes. After a few kilometers, the dirt road ends. We begin climbing a small path up into the mountains. The climb is steep, and we often have to stop and catch our breaths. Soon, the dirt and mud give way to packed snow and ice. We strap crampons onto our boots and continue climbing. It’s a long way up. Occasionally we hear trains making their way through the valley. There is a circle tunnel just south of us where the train makes a loop as it climbs into the mountains. There are few birds, but its winter. Although these are the Magpie Crags, I don’t see any magpies.

We take a break and eat lunch at a spring located below Sangwona Temple. Seung Hwan explains that pilgrims stopped here to bath and purify themselves before going to the temple to pray. The water is cold and refreshing. The wind comes up. We both pull on heavy coats, keeping in them on for the final climb.

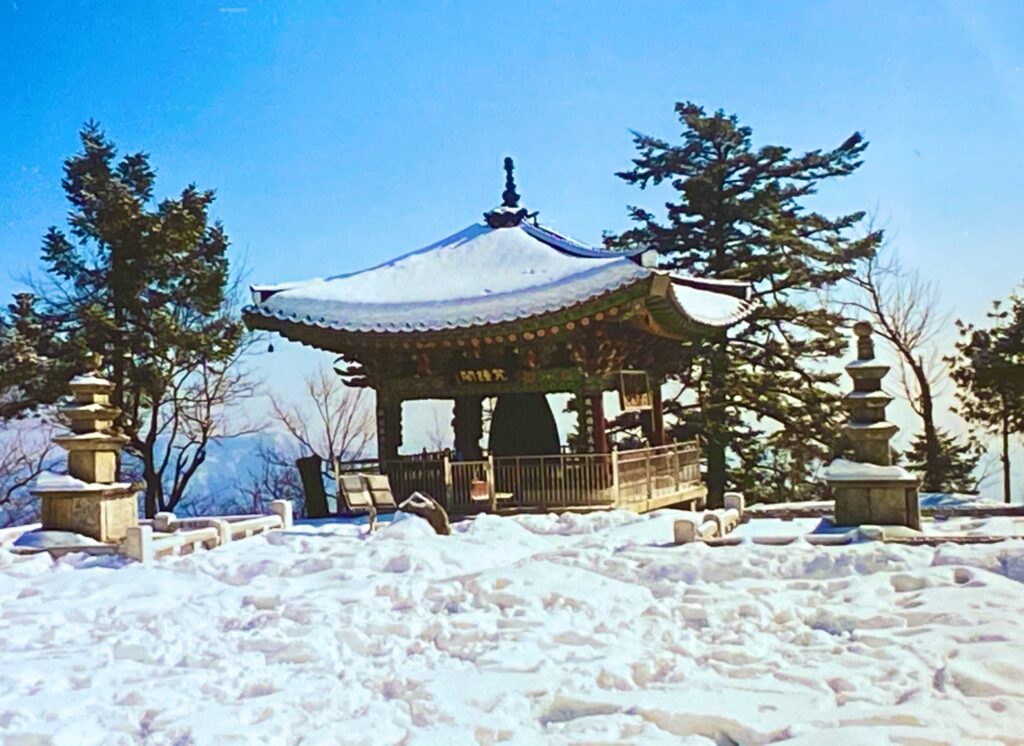

The Temple

The temple appears to be deserted, although it’s well-kept. We see only one monk, walking away. The most notable feature of the grounds is the bell. Cast out of bronze, it’s as tall as me and mounted on the side of a ledge that looks out to the South. A large log, suspended from two chains, is used to strike the bell. The monks have taken precautions and have padlocked the bell so that tourist like us won’t ring it at an inappropriate time. I ask Seung Hwan if this is the bell I heard in the morning. “Probably not,” he said. “There are many temples in these mountains.” The bell I heard most likely was from the Ipsoksa Temple, located on the flanks of Mount Pinobong.

We take our shoes off and go inside the temple area. Several beautifully cast statues of Buddha are on display. Although we’re both Presbyterian, we are respectful and reverent. There is a holy aura about the place. I could stay here a long time, but we don’t want to be caught out in the dark.. Going down is easy. The spikes on our boots hold our feet on the icy spots. As we walk, I ask Seung Hwan about the temple and its bell. This is rugged country; it took a Herculean effort to build such a temple. I can’t imagine hauling the statues and wonderful bell up this incline.

The Legend of the Magpies

Seung Hwan tells me the temple was built late in the Shilla Dynasty, at a time when Confucianism was taking root in Korea. Soon thereafter, under the Yi Dynasty, Buddhism was seen as an enemy of the people. Many of the temples were closed due to the lack of priests. Then he tells me a story.

Once Confucianism became entrenched in Korea, anyone desiring in a government position had to take a national exam at the capital. One day, a man passed along the mountains in which we’d been climbing, heading to take the exam. A kind man, as he made his through the valley in the shadow of the mountain we’d been climbing, he heard a bird cry for help. Looking around, he saw a snake squeezing the bird that would soon be its dinner. Feeling compassion for the bird, the man shot an arrow into the snake, killing it but freeing the bird.

Shortly afterwards, as it was getting late, the man came to a home. He knocked on the door and a beautiful woman answered. He asked for lodging and she agreed. She even prepared him a wonderful dinner. But after dinner, the woman turned into a snake and wrapped herself around the man, telling him that he’d killed her husband and now she was going to do the same to him. He begged for his life and the snake, playing with the man, said that if the bell rings three times before dawn, he’ll be spared. Otherwise, she’ll kill him in the morning.

This was a cruel reprieve. Both the snake and the man knew there were no monks living in the mountains to ring the bell. So, the man spent the night embraced by the snake, waiting for a fateful sunrise. But right before dawn, the man and the snake were surprised to hear the bell ring. The first time, it was very loud. Then it rang a second time, a bit weaker. Then they heard a very weak third ring.

The snake kept her word and allowed the man to go free. Instead of heading on the capital, he decided to climb the mountain and to see who it was that rang the bell. Sure enough, the temple was empty. But there under the bell was the bird that he’d saved the day before, its beak shattered from having flown into the bell three times. To this day, the bell is known as the “Compassion Bell.”

Another restful night

That night, back at the retreat house, a light breeze jingles the wind chimes along the porch. Tired and sore after climbing in the mountains, I immediately fall asleep upon the warm floor. Again, I wake at 4 AM with the toll of the bell. It’s more muffled than the morning before. I’m surprised I’m not sore from the climb. This sleeping arrangement is magical. And again, as with the morning before, I get up and go outside. A light snow falls, dusting the ground.

Beverly Willett, Disassembly Required: A Memoir of Midlife Resurrection (New York: Post Hill Press, 2019), 269 pages.

Beverly Willett, Disassembly Required: A Memoir of Midlife Resurrection (New York: Post Hill Press, 2019), 269 pages.