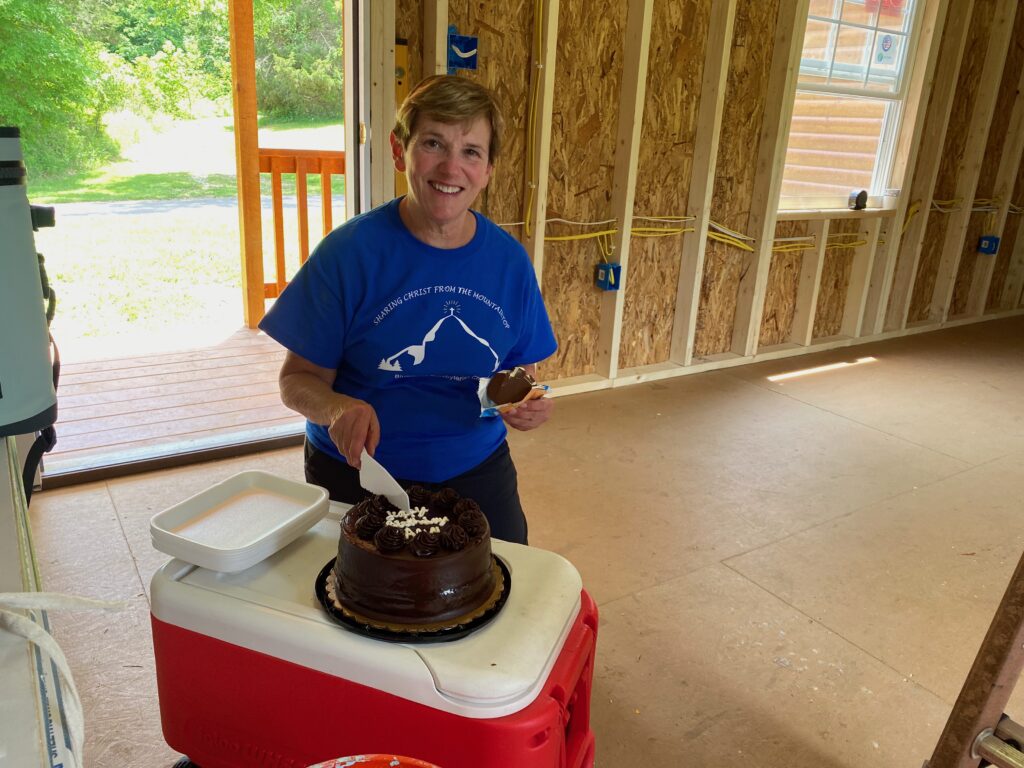

I wrote this article about 20 years ago and it appeared in the Presbyterian Outlook in 2007. I’ve added some color photos, but sadly this was in my “pre-digital” era, so there are not as many photos as I’d take today. In total, I have been on six mission trips to Central America (Honduras, Costa Rica, the Yucatan, and Guatemala. In my first trip to Honduras, from which many of the photos were taken, I was part of a construction team that build a pole barn to serve as a wheelchair storage and repair facility for the country.

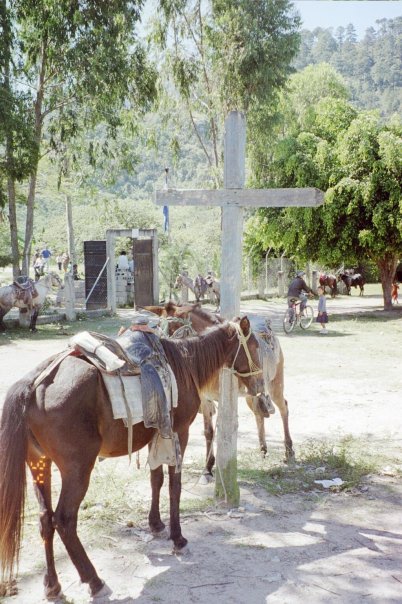

Down the highway, dodging potholes, we pass yet another bicycle struggling up a hill, firewood strapped to the back. The biker cut and split the wood with the machete strapped to the top. Life’s hard here. Turning into the village, the road becomes dirt. Chickens scoot to the side, letting us pass. The roosters puff out their chest, fluffing feathers. It isn’t just a self-assured prestige. They’re important to the economy; their nightly dalliance with the hens produce eggs, a staple in the diet of the people, and along with beans the main source of protein. At the corner, a few men lean against the wall of a pulperia (small store), cowboy hats tipped back, watching the day pass. I wave. “Hola,” they mumble as they nod. A malnourished dog darts across the street, stopping to lick the salt off a discarded wrapper of chips.Time slows down here; moving even more slowly than the bus negotiating puddles and driving around an oxen-pulled cart hauling adobe blocks.

Dark clouds and light drizzle slow life even more. It’s cool in the mountains, but never cold. Smoke rises from the stovepipes, only to lie low, forming a blanket over the town. I imagine women inside, patting out tortillas while tending the stove. The long-split pieces of wood are gradually fed into the adobe firebox. A pot of beans boils while tortillas bake on the hot metal above the coals. Their evening meal of beans and tortillas will be supplemented with a few eggs, some crumbled cheese, fresh bananas, and strong coffee.

We pass the park. Schoolboys play soccer, and a few kids shoot basketball, paying little attention to the dampness. We turn off the main road and pull up to the Hotel Central Otoreno where we get out. We’re back. The first thing I notice is that there is now a metal railing around the balcony. Last year, a couple of us got some rope and made a railing to reduce the risk of falling off the top floor. We’re assigned rooms and I haul my backpack up to the second floor, dropping it into my room. I look around. There are two beds and a chair in the main room. The TV on the wall is another surprise. It wasn’t there last year. The bathroom consists of a toilet, trash can, a sink with only cold water and a shower. I’m surprised to see they’ve attached an electric heater showerhead. Upon closer examination, I notice the ground wire has been snipped off and the hot wires are just twisted together and taped, dangling above the shower. Obviously, there are no electrical inspectors in these parts.

I head outside. Walking through the town, I visit familiar sites. The old church by the square is open. A machete, secured in a fancy sheath, lies next to the doorsill as a reminder that this is a sanctuary. I peek in and see the back of a lone man kneeling in prayer under the gaze of a rather dark-skinned Jesus who hangs on the cross. Nothing has changed. I stop in the hardware store and surprise Ricardo. He tells me he’s been practicing and challenges me to a game of chess. A customer comes in and he must return to work. We’ll meet later. I head down to the park and shoot a few hoops with the kids. I teach them useful techniques with corresponding English words, like “break” “drive,” and “pick.” Their laugher is contagious. Despite the mud and trash and poverty, I’m still at home.

I am here on a mission trip. It’s my second visit and our congregation’s sixth to this city in the central mountains of Honduras. There are approximately 20,000 people in Jesus de Otoro. Our medical team will see nearly a thousand of them over the next few days.

For the past six years, members from several Presbyterians congregations in Michigan and Indiana and a Christian Reformed Church in Iowa, partnering through Central Christian Development of Honduras (CCD), have worked to improve life in the small Honduran Mountain town while sharing the love of Jesus Christ with its residents. Under the leadership of Dr. Jim Spindler, a retired physician from Hastings, Michigan, yearly medical and dental teams have traveled to Jesus de Otoro and the surrounding villages. In 2003, Jim asked one of the Honduran physicians what would make the biggest difference to them in their practice. He was told of their need for wheelchairs. Asking how many they could use; Jim was shocked to be told that they could use a hundred. Coming back to the states, Jim set in motion a wheelchair collection program that gathered over 125 wheel chairs. First Presbyterian Church of Hastings partnered with Wheels for the World, a ministry founded by Jodi Eareckson Tada and dedicated to providing wheelchairs to impoverished areas around the world. Wheels for the World arranged for the shipment of wheelchairs and other needed medical supplies to Honduras.

In additional to medical work, the churches have provided Vacation Bible School opportunities for children of the community and have supported the work of the Georgetown School, a small Christian bilingual elementary school in Jesus de Otoro. Esperanza Vasquez, the school’s principal, received a scholarship to study in the United States. Upon returning to Honduras, she founded the school to prepare Honduran children for leadership within their community and country. During our week there, the older students at the Georgetown School, those proficient in English, serve as translators for the doctors, nurses, and dentists in the clinic. In doing so, they learn the importance of service to their neighbors while providing our medical teams a valuable skill in communicating between the doctors and patients.

Our trip to Honduras in the Fall of 2005 had a rough beginning. Shortly after landing in San Pedro Sula, Honduras’ largest city, we realized we were in the sights of Hurricane Beta, the last of the season’s Class Five Hurricanes. We decided to spend the night in the city and see what the storm would do. Our hosts from CCD were nervous about us going into the countryside due to the possibilities of floods and mudslides, which could trap us for weeks. They still have strong memories of the devastation of Hurricane Mitch in 1998.

That morning things looked ominous. The front page of the newspaper had a map of the projected path of the storm, showing it moving over central Honduras, right where we were traveling. We stayed in San Pedro Sula, preparing to ride out the storm if it came our way. We purchased food and batteries and plenty of five-gallon jugs of water. A few team members grabbed what seats were available and flew back to the United States. Throughout the day we checked the weather on the internet at the hotel. By evening things were looking good for us, but not so good for those who lived along Honduran/Nicaraguan border and in the Nicaraguan Mountains. We held a worship service that evening in the hotel lobby, praying for the victims of the storm. The next morning, we moved inland where we began our work, having already lost two days.

Once in Jesus de Otoro, our day begins with the crowing of roosters. Starting about 3 A.M., hundreds of roosters throughout the valley try to outdo the others, ensuring that the last couple hours of night will be restless. By the third night, we’re used to it. In the predawn hours, the town slowly comes alive. Before getting out of bed, trucks can be heard banging along the pot-holed streets, loading workers in the back for a day in the fields or in factories in Siguatepeque. Smoke from cooking fires, held down by the heavy humidity, fill the air as we get up and prepare for the day. Our hosts from CCD have breakfast, supplemented by rich Honduran coffee, ready by 7 AM. Afterwards, we head over to the clinic where a crowd of people have already gathered. We work steadily until lunch and then return in the afternoon and continued till dinner. Hundreds of people are seen each day.

My duties as a pastor include handing out copies of the New Testament and tracts and praying for and with those waiting for a doctor. In broken Spanish, I welcome them in the name of Jesus, and then an interpreter takes over. I play with the children who understand the universal language of laughter. At the end of each tiring day, we have supper before gathering for worship in a small local church where we share our stories and testimonies with one another. We put in three full days, our work cut short by the hurricane, before we leave the community. Not everyone was cured or even seen, but seeds of hope have been sown as the residents of the region have come to know that someone cares.