I wake up as the train crosses the Potomac, heading into the DC Station. I don’t get up, but continued napping as the diesel locomotives were traded for electric ones. Fifteen or so minutes later, we pull out of Washington and continue northward. Around mid-morning, I step off the train in Philadelphia. Shari stands at the end of the platform waiting. I have a long layover before catching the Pennsylvanian, a train that will take me overnight from Philadelphia through Pittsburgh and on to Chicago. (Today, the Pennsylvanian only runs to Pittsburgh).

Philadelphia

As it was Sunday morning, Shari drove into the city. I toss my bags into the back of her car and we stop at a bakery at the end of Fairmont Park for breakfast and coffee. We catch up on our lives as it had been nearly two years since we met along the Appalachian Trail at Delaware Gap. Having recently finished law school, she is debating two job offers to teach legal writing, one at Catholic University in Washington and another at Western Mass Law School in Springfield.

After breakfast, we walk over to the Philadelphia Art Gallery. We see Robert Adams collection of American Western photos along with several Monet and Van Gogh paintings. I was shocked to learn Shari doesn’t care much for art galleys, so we head across the river and walk around the zoo. Later, we drive across town to the old part of Philadelphia. There, on South Street, Shari insists on treating me with an authentic Philly Cheese Sandwich. This is a real treat, as she’s a vegetarian. She’d asked friends for the best place to buy me a sandwich. We then walk around the old city, stopping to look at the Liberty Bell, Independence Hall, and checking out Benjamin Franklin’s pew at Christ Church. As a Jew, she was more than willing to indulge my curiosity inside the church. Then it was time to head back to the Amtrak Station.

On the Chicago

That evening, as the train ran across Pennsylvania, I had dinner with a guy name Tim. He works in the computer import business and has spent a lot of time in Seattle. He provides several suggestions on getting around in the city and what to see. After returning to my seat, I alternate reading my academic advisor’s new book, Beyond Servanthood and Adela Yarbro Collin’s, Crisis and Catharsis: The Power of the Apocalypse before falling asleep.

Chicago and McCormick Theological Seminary

We arrived in Chicago on time, early in the morning. Having been given directions to McCormick Theological Seminary in Hyde Park, I walk a few blocks to the east and take a regional train. At the seminary, I’m met by several students whom I had worked with at the General Assembly in Saint Louis the previous summer. They introduce me to more students. We attend chapel together, then they arrange for me to take a shower in a dorm, before meeting for lunch. Afterwards, Marj, one of the students I knew from St. Louis, insists on driving me back to the Southshore Station, which was about a mile away. She had suggested I call when I arrived there and she would have picked me up, or I should take a cab. But I decided to walk down and surprise them. Undoubtedly, the neighborhood is worse than it looks. I take the Southshore back into the city center city to catch the Empire Builder that afternoon for Seattle.

While walking back to Union Station, I was surprised to be greeted by two kids running up to me. Aaron and Ashley and their mother Karen, whom I’d met on my journey from Pittsburgh to Washington, sit just outiside of the depot, while waiting on their train to Grand Rapids, Michigan. They’d just returned from their trip to the Nation’s Capital. We have enough time to grab an ice cream before I boarded the train to the West Coast.

Chicago to Seattle, Day 1

The Empire Builder, the northern most of the great western railways was built by and named for James J. Hill. He envisioned a railroad across the northern plains, connecting the twin cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis to the Pacific. The line runs just south of the Canadian border. The Amtrak line which goes by the same name, starts along the old Milwaukee Road line from Chicago and then picks up Hill’s Great Northern line at the Twin Cities.

My train leaves Chicago late in the afternoon. I finish reading Sue’s book, Beyond Servanthood, before bed. Sometime early in the morning, we stop in the Twin Cities. I don’t even get up and quickly fall back asleep.

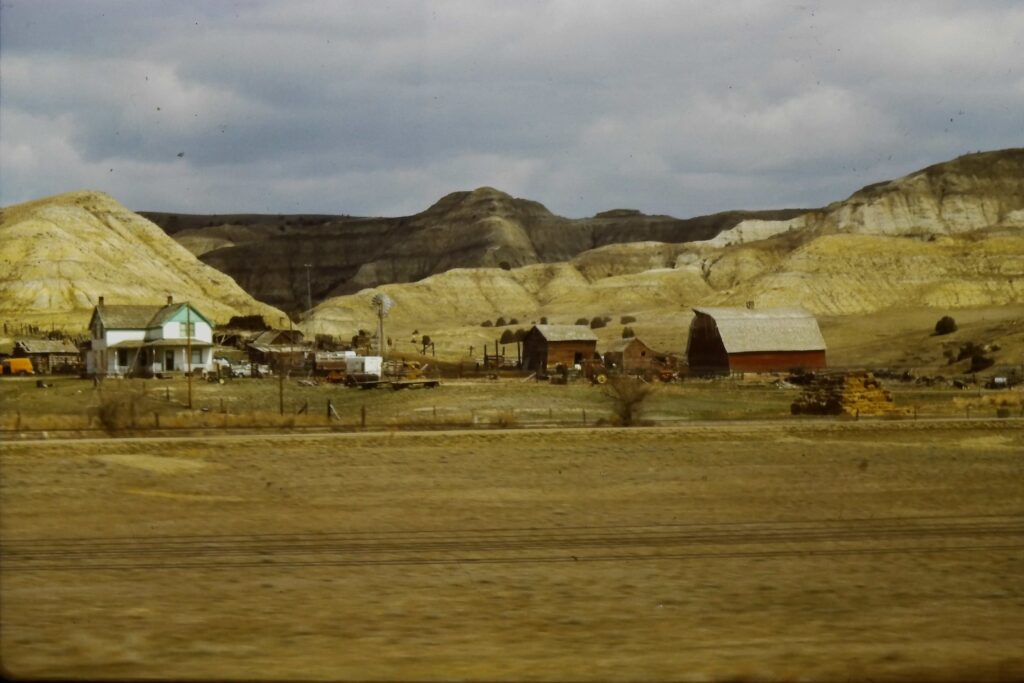

The next time I awake, the train gently rolls through curves, its wheels squeaking as they rub against the rail. I opened the curtains to see a thin strip of pink in the sky. I assume I’m looking out for the first time at North Dakota. A thin blanket of snow lays along the flat prairie, broken by an occasional row of trees or a line of utility poles. At regular intervals, a larger clump of trees indicates a small village. Above the trees stand a church steeple, water tower, and grain elevator. Nothing moves. Empty grain hoppers sit on sidetracks, waiting for the next harvest. A few cows huddle near isolated barns. I make out the silhouette of tractors, waiting for warmer weather. The state seems to be in a late winter nap. Then the train pulls up to the platform and I see the sign for Detroit Lakes. We’re still in Minnesota. I fall back asleep.

Fargo

Our next stop is Fargo. The town hadn’t yet been made famous by the Coen Brother’s black comedy. I step off the train and take a brisk walk up and down the platform. My breath smokes like a steam locomotive in the cold air. But it wakes me up. After a few laps, I hear “All Aboard,” and step back onboard and head to the lounge car for coffee. I sit and watch the prairie as the day awakes. It’s spring but feels like it’s still winter. I can’t imagine the harshness of life up here along the high line, cold winters and hot summers.

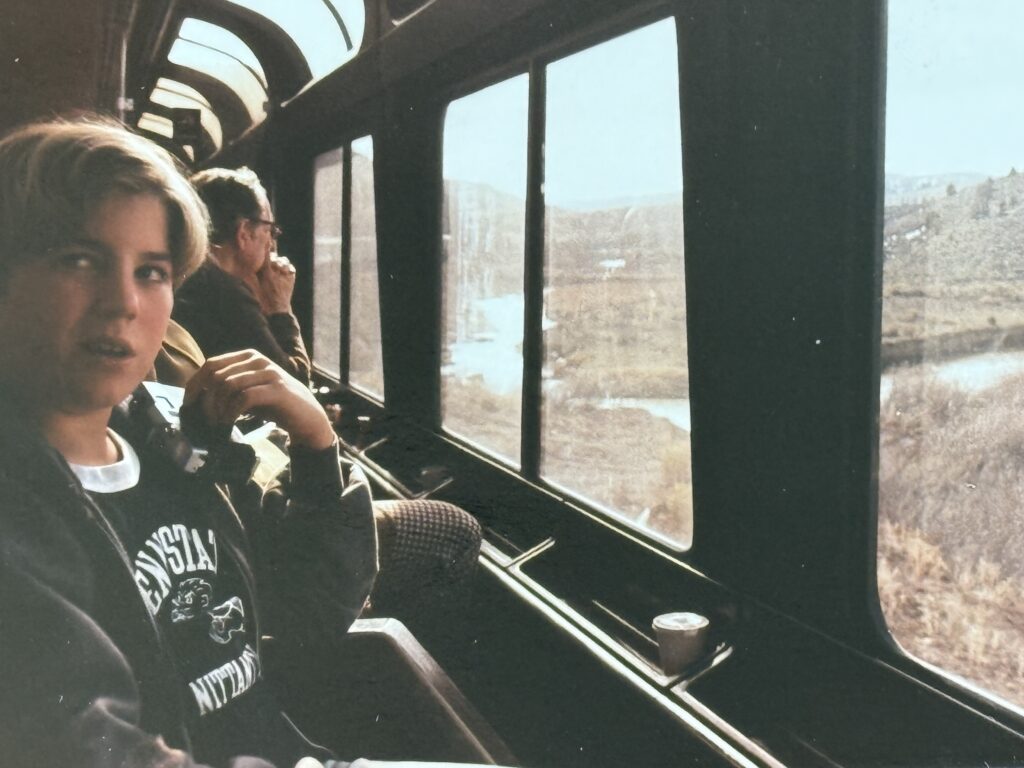

I spend much of the morning alternating between looking out of the window and reading. Having tired of theology, I pull out the one book of fiction in my bag, Doris Lessings, The Summer Before the Dark. It wasn’t light reading, so I spend much of the time looking and talking to fellow passengers.

Delay

We’re running behind a bit, but late morning we come to a full stop. We’re informed of a train derailment ahead of us which needs to be clear. We sit, looking at the same barren prairie for two hours. The fences that run alongside the tracks seem mostly to corral tumbleweed. After we resume, I get off at all the towns where there’s a smoke stop, walking a few laps around the platform as the smokers puff down their cigarettes.

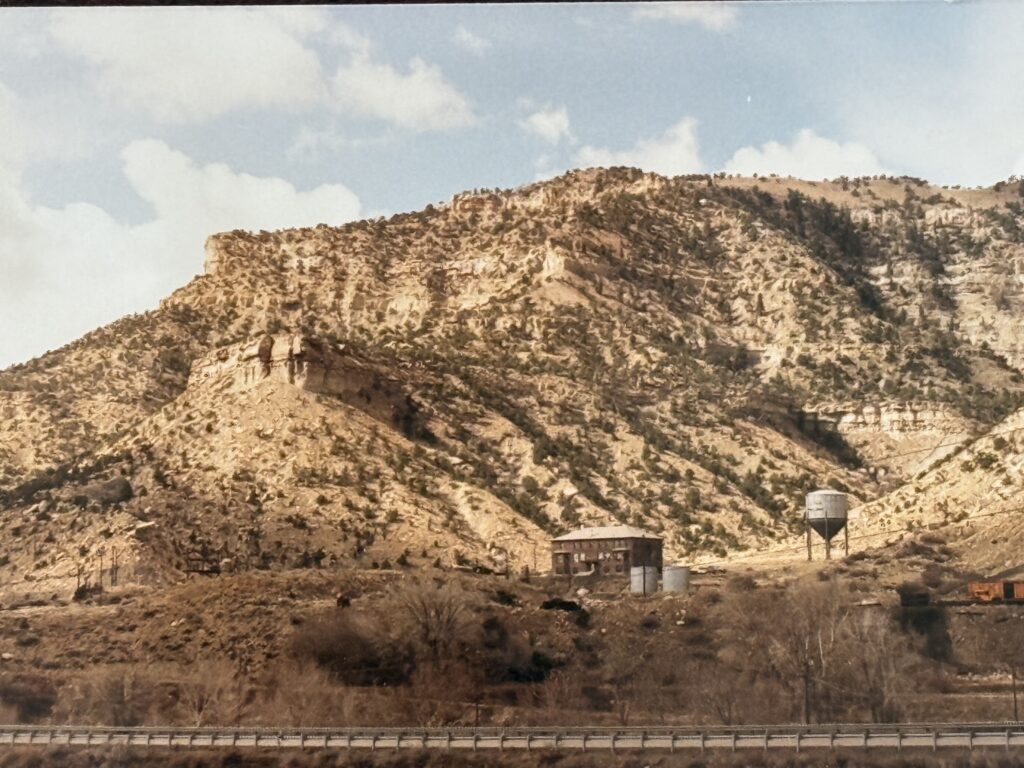

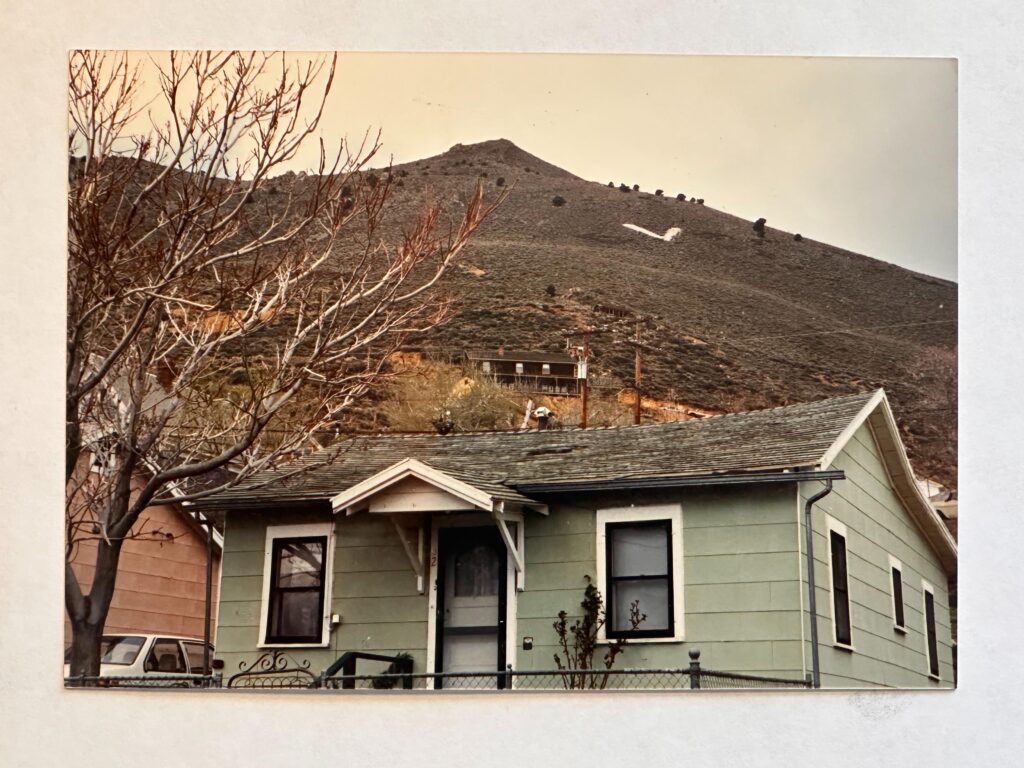

The further west we travel, the more familiar the landscape seems. I spot sagebrush and, in my journal, use the term “Sage Covered Hills,” first the first time. For years, it would be the name of my blog. Some of the towns have painted their initials on the hillside above them. This common western feature I first spot on a hill above Glasgow. There are massive powerlines pulling electricity from places like Fort Peck Dam. At the time, I knew nothing about the dam. Later, I’d become more familiar with it through the writings of Ivan Doig, a Montanan author.

Chicago to Seattle, Day 2

As the sun sets, we can make out the distant mountains. Running several hours behind due to the derailment up ahead means we’ll not see the majestic peaks as we cross into the northern Rockies. It’s two hours after dark when we arrive at Glacier Park Station. Instead of a light dusting of snow, as I’d seen in the morning, the mounds of pack snow are head high all around the station. A few passengers get off and others come aboard and soon we’re slowly climbing in the darkness.

I wake up at dawn and we’re in Spokane, having crossed the Rockies in the dark. Here, the train splits with part of the train heading to Portland, while the rest of us will continue to Seattle.

We run through eastern Washington and arrive in Seattle at midday. This is unfamiliar country to me. Years later, when I read David Guterson’s East of the Mountains, I recalled my trip across the state. I wished I had made more journal entries as I traveled reverse of Dr. Ben Givens, the novel’s protagonist.

Seattle

In Seattle, I gather my luggage and head to my hotel, two blocks away. I’m too early to get the room. I leave my luggage at the counter and set out to find lunch. Afterwards, I head to the Space Needle for a view of the city. I ride the city’s cable cars and walk along the wharfs and fish markets dotting the water. Later, I find a place to have seafood for dinner. I head back to the hotel before dark, wanting to sleep in a bed without waking up at stops. From the room, I call Carolyn and am surprised when she tells me she’ll meet me in Sacramento in two days. I’m both excited and nervous.

On the Coast Starlight to Sacramento

The next morning, in a misty rain, head back to the train station and checked my bags for home. The sky is hazy as we pull out of the station on the Coast Starlight. I can barely make out the shapes of St. Helens, Ranier, and Hood of the Cascade Range. This overnight train runs almost 1400 miles, connecting Seattle with Los Angeles.

I get off early the next morning in Sacramento. My ticket was for Oakland/San Francisco, where I would transfer to the California Zephyr. But since the Zephyr also stops in Sacramento, this allows me to avoid riding the same track and provides me with most of the day in California’s capital. It’s a beautiful day and the city is just waking up. As I arrive an hour before Carolyn, I hike up to the bus station, maybe a mile away. I stop for coffee and then, thinking it’s about time, walk on over to the station. Her bus is early and she’s leaving the station, when I call to her. We hug and set out to see the city.

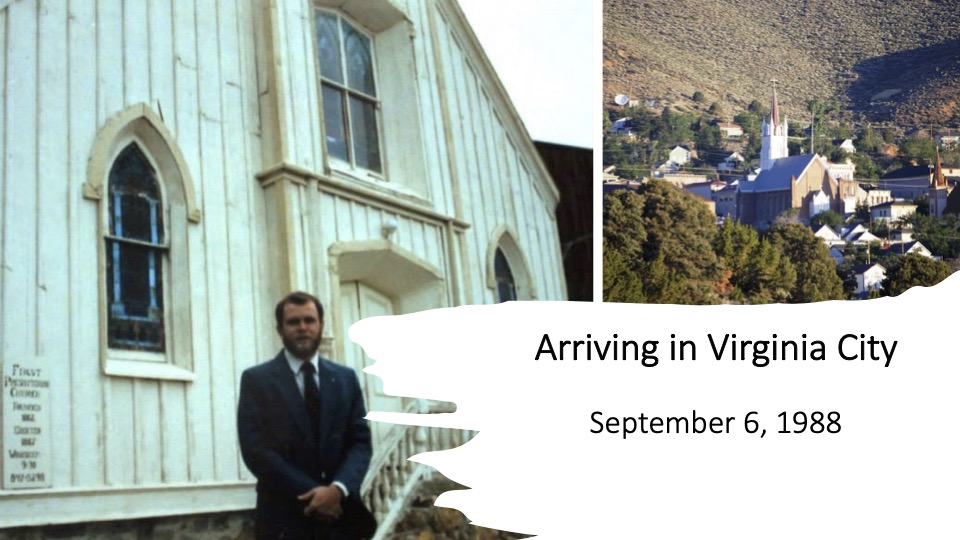

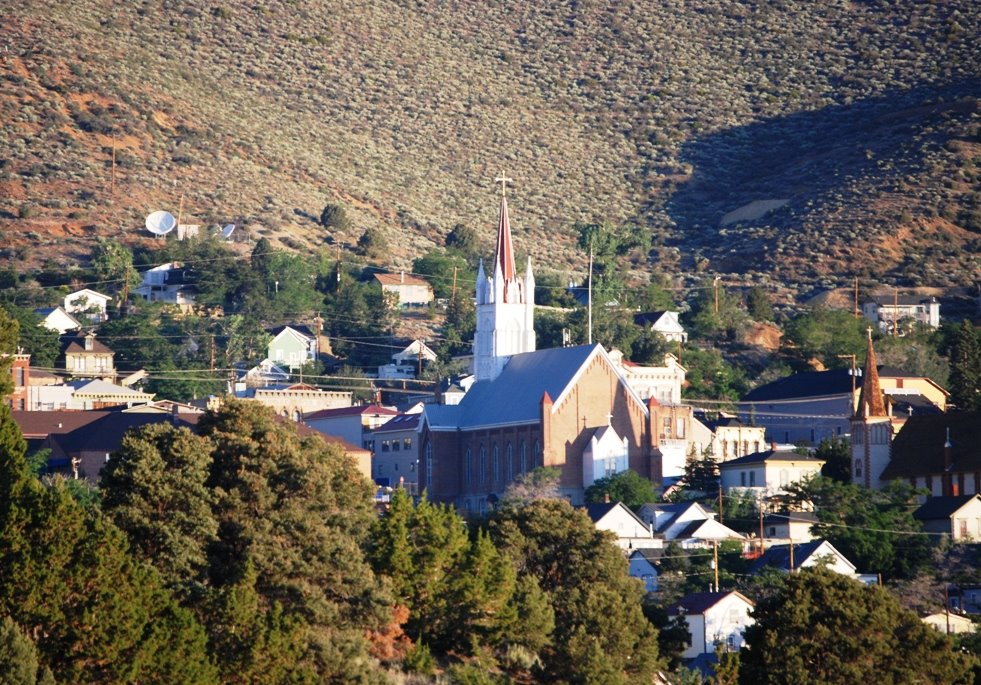

Of course, nothing is yet open. We walk around the state capitol. Then we head to the Roman Catholic Cathedral. This had been built by the first Catholic Priest in Virginia City after he was made a bishop. Then, when the California State Railroad Museum opens, we head there. This is one of the premier railroad museums in the world and we spend the rest of the morning exploring. After lunch in the snack bar, we head back to the train station to the ride back to Reno.

The final lap to Reno

The ride across the Sierras is familiar as the tracks mostly parallel Interstate 80. The train twists and sways and often runs through snow sheds, designed to protect the tracks from avalanches such as one in 1954 which stranded a train for a week. We mostly sit in the lounge car, close to each other, our feet propped up on the rail below the window, as we take in the scene. After the stop in Truckee, we head back to our seats and collect our baggage. In Reno, where I started nearly three weeks earlier, we step off the train.

Other train trips

Coming home to Pittsburgh, 1987

Doubly late to West Palm Beach, 1986

Riding on the City of New Orleans, 2005

Riding in the Cab of the V&T, 2013

Riding the International: Georgetown to Bangkok, 2011