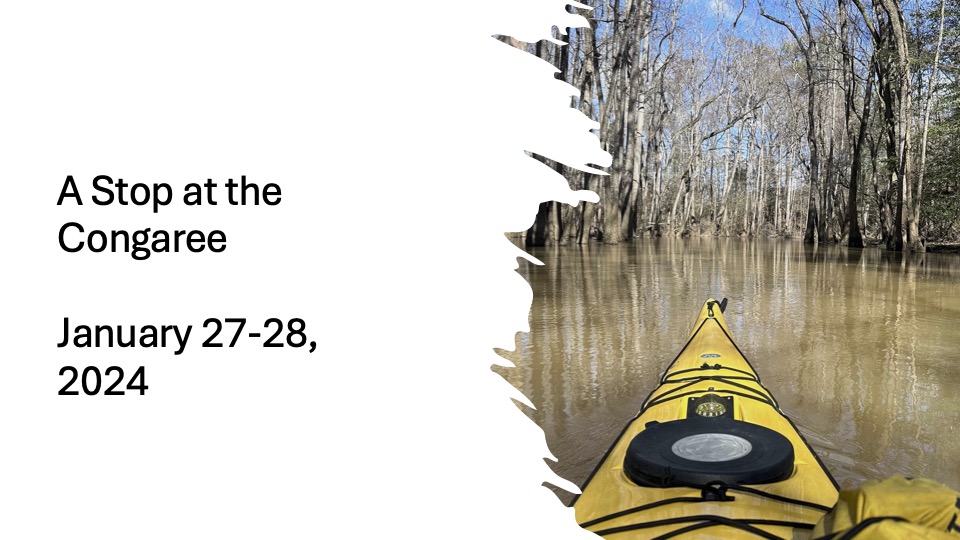

As I hadn’t planned on returning home until Monday, I decided to add another stop on my return. I have wanted to visit Congaree National Park in central South Carolina. The park is one of the nation’s newest, established in 2003. It’s also one of the least visited parks in the nation. The park consists of river bottom land along the Congaree River, which tends to flood. A few weeks before I arrived, 80% of the park was underwater. While I was there, the water within the park was once again rising.

Cedar Creek flows through the middle of the park, paralleling the Congaree River, which forms the park’s southern boundary. To the north, the land rises above the lowland, creating an area ideal for longleaf pine forest. Sadly, there are few longleaf, but I’ll get to that later.

Leaving Folkston, Georgia, I determined to stay off the freeways. I followed US 301, through small towns in South Georgia, Nahauta and Jessup. This was familiar territory from my time living in South Georgia. The GPS on my phone drove me nuts as it kept trying to lure me back on I-95. The GPS even said it was the safe route as the National Weather Station reported flooding on other routes. I found myself rerouted to the interstate. This I discovered this when I arrived in Hinesville. Turning the GPS off, I take a road that cuts through Fort Stewart, and picked up 301 again. I drive through Claxton (the world’s fruitcake capital) and Statesboro and Sylvania, where I stopp for a late lunch in a Chinese restaurant. While the rivers are high, they are nowhere near cresting over the bridges.

Crossing the Savannah River on an old bridge, I enter South Carolina. As I drive on, I listen to Edward Chancellor’s Devil Take the Hindmost, which is a history of economic speculation. Traveling through towns like Allendale and Bamberg, who appear to have long passed their better days gives me time to ponder what happens when an economic bubble bursts. I passed through Orangeburg, probably the largest city that I passed (Statesville might be larger, but I only skirted around it).

When I crossed Intestate 26, running from Charleston to Columbia, I stop and grabb a burger for later, knowing that I didn’t feel much like cooking.

I arrive at the Congaree National Park’s Longleaf Campsite at dusk. It’s a walk-in campsite, so I lung my waterproof bag containing my hammock, tarp, and sleeping bag a few hundred feet to my assigned site. I quickly set up my hammock, for there was heavy lightning to the north. But the storm took another path and by the time I was set to withstand the storm, the lightning has disappeared.

I then set out to explore. The waning moon, only a few days after full, rose and offered plenty of defused light. I hiked the longleaf trail to the Visitor’s Center. Of course, everything was closed, but in the darkness, I came to understand that the name of my campsite and the trail to the Center was aspirational. I was camping and hiking under loblolly pines, the type of pines loved by paper companies. When the old growth longleaf were cut, they were replanted with loblollies, as they grow faster. The loblollies have shallower roots than the longleaf, who grow deep roots before they grow tall. The only longleaf I’d seen in the dark were a few youthful plants near the outhouses.

Returning to my campsite, it begins to drizzle. I retreat into my hammock and read a few chapters of Cecile Hulse Matschat’s The Suwanee: Strange Green Land, before falling asleep to the sound of rain. It rained off and on throughout the night.

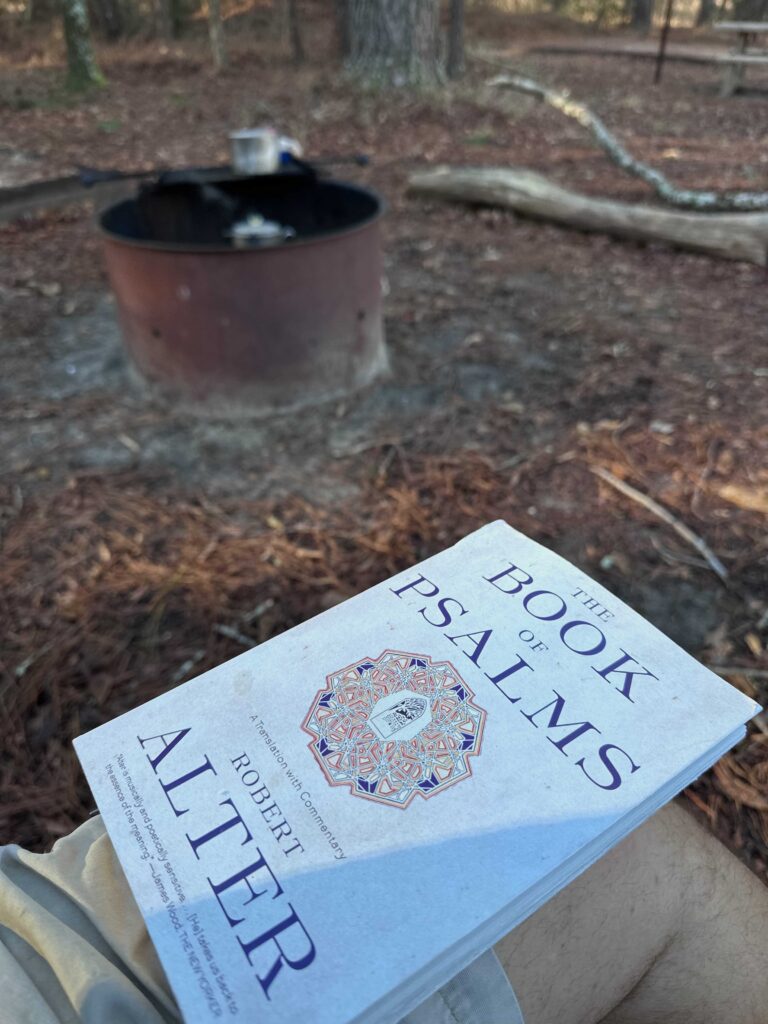

(inside the fire pit because of the wind)

While I had enough water for the evening, I have to go find water for breakfast. I hike back to the Visitor’s Center and fill a couple of liter bottles. Coming back, I perk a pot of coffee and make some oatmeal. The wind slips through the pines as I enjoy breakfast. In honor of the Christian Sabbath, read several Psalms and commentaries in Robert Alter’s The Book of Psalms. The sun burns the fog and clouds away. Along with the wind, my tarp dries by the time I finish breakfast. I pack up a head back to the Visitors Center where most of the trails originate.

The park has an amazing 2 ½ mile long boardwalk that takes you deep into the cypress lowlands. At places, the water is just below the walking path. I can see where, a few weeks ago, the water crested over the boardwalk. When I get to the trail to the river, I take it, but only make it about a half mile before the path is blocked by running water. I return to the boardwalk.

Along the way, I pass one of the largest loblolly pines I’ve seen. It’s huge. This is the natural location for such trees, as they tolerate water around their base better than the longleaf pines. These trees are obviously old growth and this one next to the boardwalk is thought to be the largest pine in South Carolina.

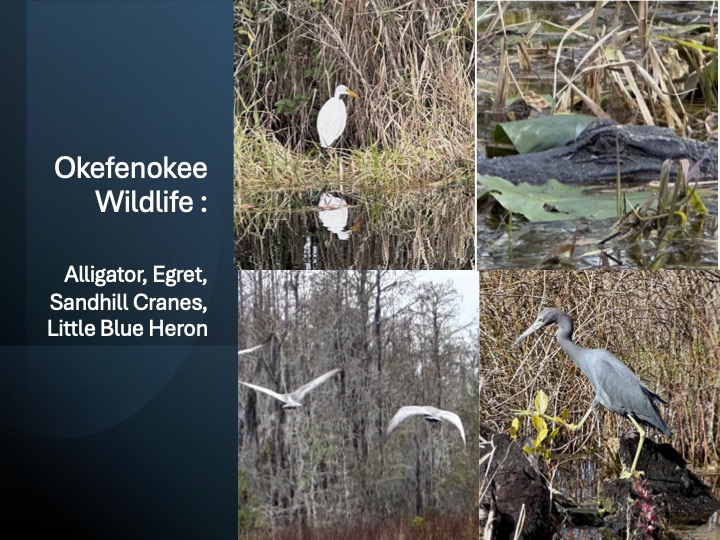

These bottomland swamps, populated with cypress, loblollies, holly, and tupelo (gum) trees remind me of the swamps I started exploring as a teenager in Eastern North Carolina. While there is some similarity to the Okefenokee, it’s also different, especially with the amount of tupelo. After hiking about 4 miles, I make it back to my car and drive to the boat landing on Cedar Creek. I must get one more paddle in before driving home.

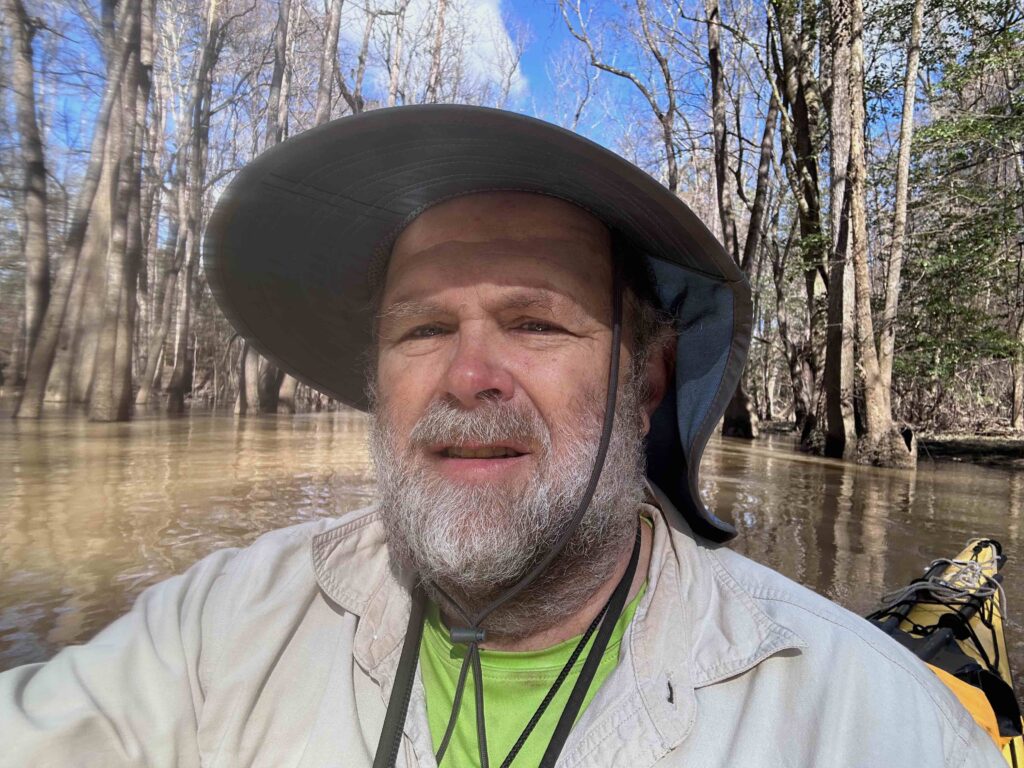

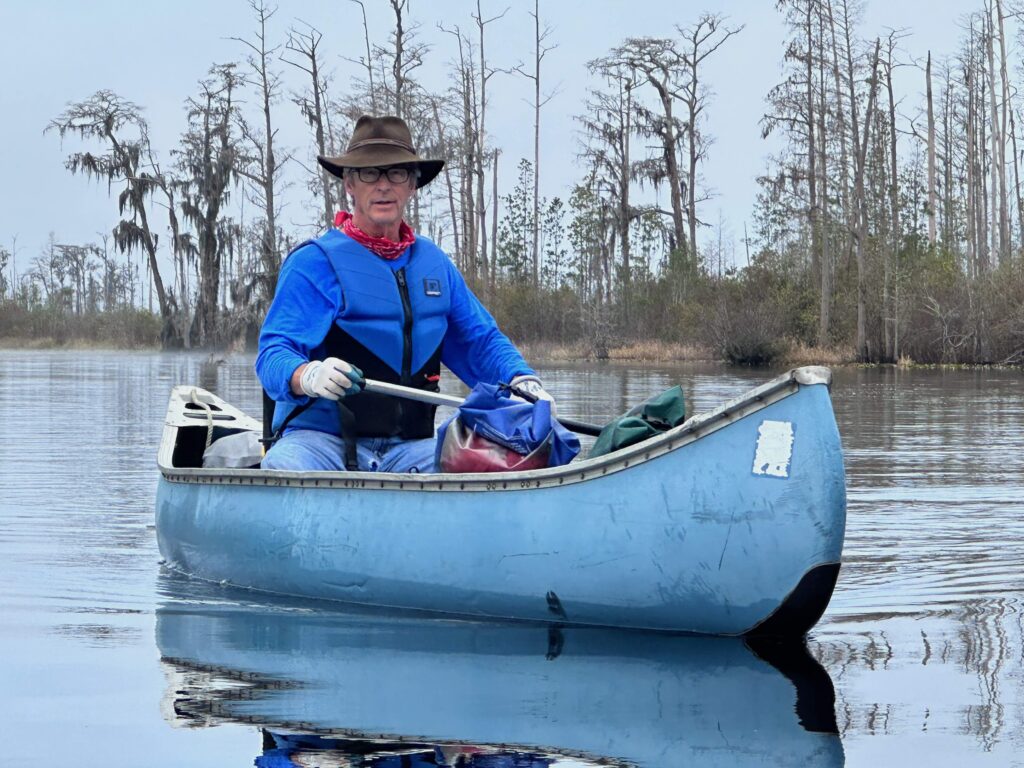

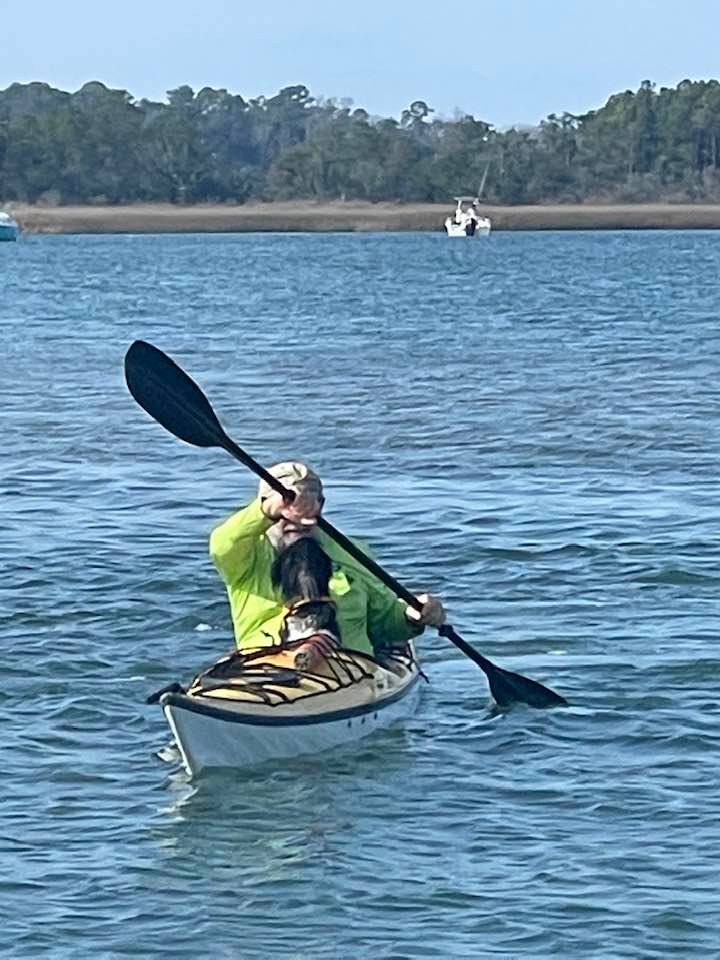

I eat lunch at the boat launch on the edge of the National Park boundary, a few miles from the Visitor’s Center. From the number of vehicles, it seems there are many others on the water, and a few are hiking, even though much of the trails are underwater. As I’m putting in, I speak with a guide who is bringing back a couple of patrons from a paddle. The water is high. He informs me that you can only make it about a mile upstream and three miles downstream. I head out, paddling upstream against the hard current for about 30 minutes, till I arrive at a place I can go no further without pulling my boat over a log. Then, I turn around and make it back to the takeout in only 10 minutes.

I continue going downstream for a few miles, passing many boaters struggling to fight the current as they paddle back to the takeout. This water is naturally blackish, but with the silt from the rains, it’s milk chocolate brown. As I turn around and paddle upstream, I pass many of those in small kayaks still fighting to get back to their takeout. My boat, 18 feet long, is easier to paddle against the current. I also read the water better, and am able to stay out of the fastest current.

One of the local paddlers from Columbia is impressed with my sea kayak and asks me all kinds of questions as he helps me load it on the car. He’d come down from the state capitol for a day trip and had never paddled this area. As we talk, we realize that we have probably raced against each other. He used to crew on a friend’s boat out of the Savannah Yacht Club and raced in many of the regattas I have also raced in.

A little after 3, I’m loaded up and heading north, driving the backroads of South Carolina through the Sandhill region of the state. In an old tree in a pond next to the road, I spot a bald eagle, I slow down, but there is no place to pull over. The car behind me honks his horn and gives me the “Hawaiian good luck sign” as he passes. The bird takes off. I have no idea what kind of hurry he was in, but he missed seeing a beautiful bird. As I enter North Carolina, the light fades. I cut over and take Interstate 77 toward home. Stopping only for dinner and gas, I arrive home a little after nine.