Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

August 30, 2020

Matthew 16:21-26

Click here to watch the service. The sermon begins at 18 minutes if you want to fast-forward.

Beginning of Worship: I saw a meme the other day. A man at a bar ordered a Corona and two hurricanes. “That’d be 20.20,” the bartender said. It’s not been a good year so far. It seems like we’ve all been carrying a cross over the past eight months. But is this what Jesus means when he says we are to pick up our cross and follow him?

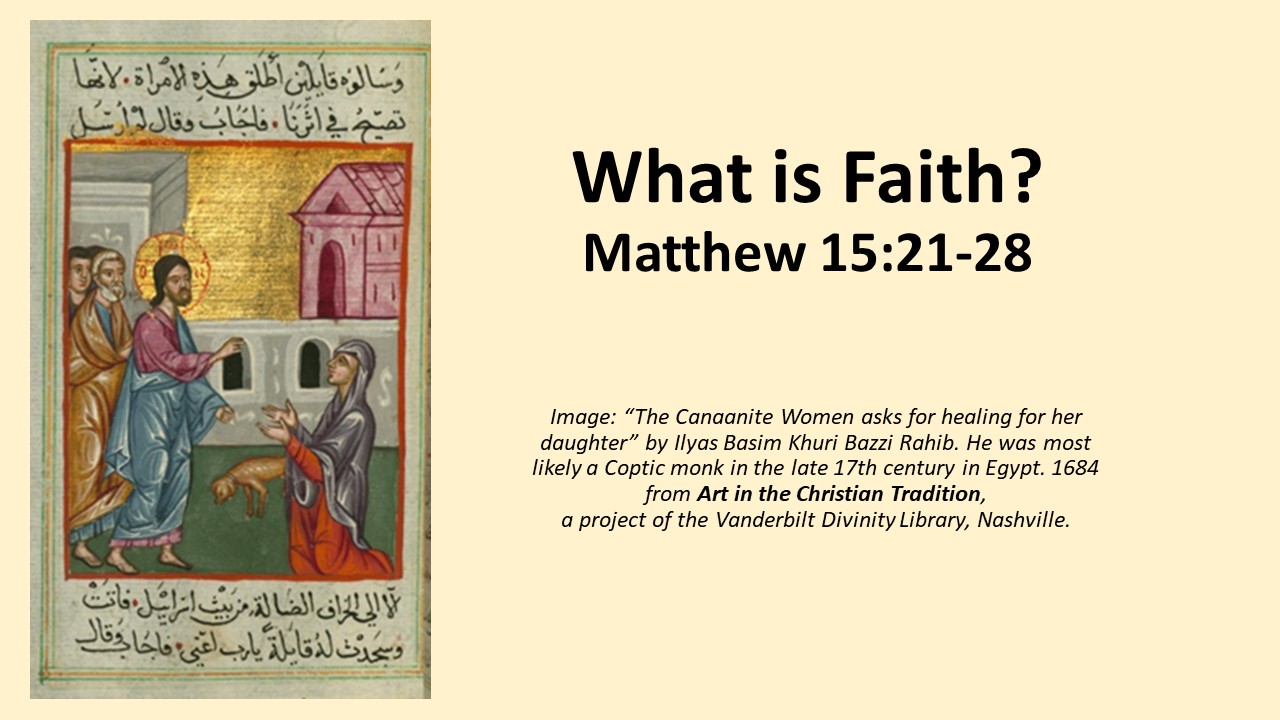

The cross is a symbol we see everywhere. We have several in our sanctuary. We wear it as jewelry. It populates cemeteries and are often placed beside the road where there has been a fatal accident. But what does it means when Jesus tells us to pick up the cross? That’s today’s topic.

This is our second Sunday in the 16th Chapter of Matthew. If you remember, last week, Peter nails it. He confesses Jesus to be the Messiah. Today, he doesn’t look so good. He can’t accept Jesus’ plan involving the cross. Last week, Peter was praised. This week, he’s called Satan. There’s good news here because our lives are similar. We can do good and great things and we can do rotten things. Aren’t you glad there’s grace?

Jesus does something radical and he invites us to follow him, but it’s a costly invitation. Jesus demands our very lives. For those of us who follow Jesus, the cross becomes our sign of God’s power as Paul eloquently states in First Corinthians, but to others it’s foolishness.[1] But as a sign, the cross is not easily understood.

###

After the Scripture Reading: What does it mean to pick up our cross and follow Jesus? Maybe a better way to ask this question is what does it mean to be a follower of Jesus Christ? We have to be careful that we don’t cheapen the bearing of our cross in an attempt to explain our trials. Carrying the cross isn’t just enduring a bad time, like 2020. Picking up our cross and following Christ has life changing implications. We admit we’re not in control. It’s no longer about us and what we want and what we think we need. Instead, it’s all about the man up ahead, the one we are following.

Think about the theology of the cross in light of two seeming contradictions in scripture: Jesus’ call for us to pick up our cross and proclaims that he’s come to set us free.[2]

In Jesus’ day, no one thought of the cross as a sign of freedom. In fact, a cross was viewed in just the opposite. It was a sign of torture, a reminder of the imperial power of Rome that subjected a huge portion of the population to slavery. In Rome, if a slave rebelled, the cross was the normal method of execution. The cross was a tool the Romans used to cement their control. When Jesus tells the disciples to pick up their cross and follow, they may have had second thoughts.

This particular passage is recounted in all three of the synoptic gospels—which tells us something about the impression it made on the disciples.[3] Yes, we know Peter doesn’t like the idea of Jesus dying, but that was all before Jesus issues this command. None of the gospels give us an idea of how the disciples and the crowd responded to Jesus’ call at this point. Such an omission is a part of the plan, I believe, for it allows us to respond to Jesus’ call in our own ways. This morning, we’re wrestling with what it means to pick up our cross. First, I am going to discuss some mistaken ways this call is interpreted: I’ll label these three as triumphant militarism, naive pacifism, and sentimentalism. Then I will offer ideas on how we are to be a servant of Jesus Christ and faithfully answer his call.

Peter’s idea of picking up the cross falls into my triumphant militaristic category. Remember, he’s the disciple who, at Jesus’ arrest, pulls out a sword and slashes the ear off of one of the men.[4] I imagine Peter, a fisherman whose muscles were well defined from working the nets, as a strong man. At this stage of his Christian walk, he’s a Rambo type character, ready to pull up the cross and use it as a club to pound his foes. Peter and the other disciples are ready for Jesus to set up a worldly kingdom. Peter wants Jesus to be King so he can be an advisor, right next to Jesus’ throne, the second in command.

When Jesus started talking about this suffering stuff, Peter gets nervous and decides he’d better try to steer his leader in a different direction. “Hey Jesus,” Peter remarks, “let’s rethink this part about dying.” But Jesus’ way wins out. The cross is not to be used by us as a weapon, nor does it give us any protection other than being a symbol of what Jesus has done for us.

If triumphant militarism is one extreme rejected by Jesus, so is the other extreme, which I label naive pacifism. I chose the term naive because pacifism for many Christians is an appropriate response. But when the path is naively chosen, we forget that we’re called to resist evil, to deny evil power in the world and instead we become a sacrificial pawn. Just as we should not use the cross as a weapon, it’s not to be used as a white flag of surrender, either. Jesus picked up his cross and carried it to Calvary in order to offer his life for sins you and I have committed. Jesus died for our sins so that we don’t need to die for them, nor should we be expected to die for the sins of others. But this doesn’t mean there’s not work for us to do.

If we’re not to be militants or pacifists, we might be led to think the proper understanding—the middle way of understanding Jesus’ call—is sentimentalism. Sadly, this is the way many people look at the cross. We clean up its horrific image and use it as jewelry and decor on our cars. But such an understanding of the cross—if it goes no deeper—misses the point. It can even become a political statement or a superstition, which is idolatry. If the cross is only seen for its sentimental value—we’ve cheapened Jesus’ call.

I don’t know if I can give an understanding of what picking up one’s cross should mean to us all. Certainly, I think it means more than having a piece of jewelry. For a few people, it may mean martyrdom—as it did for many of the disciples. But Jesus certainly didn’t expect all his followers to be crucified. Secondly, martyrdom is not the highest virtue. Instead of martyr, the virtue we strive for is faithfulness. Yet, we learn from Jesus, if we love our life we will lose it. Paul expands this thought when he speaks of our need to put to death the desires of the flesh and to live for Christ.[5]

By calling us to pick up our cross, Christ informs us that we’re not in charge of our Christian journey. We must be willing to follow him. Our calling isn’t about our needs or our desires, but about Jesus’ desire for us and for our lives. As Christians, we all have a calling that is linked to our vocations. Since we live our Christian life throughout the week, and we all have different occupations and trades, we each have to determine how we can best be true to our Savior. I can’t give a single definition of what picking up our cross will mean for everyone, just as Matthew didn’t tell us of the disciples response to this call.

As a seminary student, when I was a camp director in Idaho, we had each of the campers carry a live-size cross during a hike. Afterwards, around a campfire, we debriefed. Some told how difficult it was to physically carry the cross—toting the awkward beams and of the splinters. Others spoke about how they were uncomfortable to be out front of the rest of the campers, with everyone following and looking at them. Others had even more difficulty watching their fellow campers struggle. These wanted to show compassion by taking the burden of their friends.

These responses from the campers provide an insight into what the cross means and maybe an idea of how we pick up our crosses. When Jesus took up his cross, he was taking on the burdens of the world. He didn’t take the cross on his own behalf, but on our behalf. It wasn’t someone who lived a comfortable life that brought salvation to the world; it was someone who shared in the suffering of the whole world. We must understand that Jesus’ death on the cross is sufficient for our sins and the sins of the world.[6]

The penalty for sin—death—has been paid in full and none of us is being called to make another deposit—we’re not being called to save the world.[7] By picking up the cross, Jesus shows his willingness to share in our pains and sorrows. And he calls us, his disciples, to share in the pain of others. The campers who expressed compassion for the one carrying the cross understood, at least partly, what is means to be indebted to someone for taking on our burdens and for us to be ready to have compassion for others who are in pain. One meaning of picking up our cross is for us to be willing to stand beside others in need—whatever form that need might take. Jesus takes our burdens, he shoulders our cross, and the only way we can have a glimpse of what he feels is to feel the pain and burdens of others. So maybe our crosses have to do with how we show compassion.

I think our vicariously sharing in the pain of others also helps us to understand the proverb Jesus cites at the end of our passage. Jesus reminds us that whoever wants to save their lives will lose them and whoever loses their lives for his sake will find them. This is one of those great reversal statements of Jesus, but notice Jesus doesn’t call us to lose our lives in the lives of others. Rather, he calls us to place himself first in our lives—to put our total trust in him. Our call to discipleship is not to place some other than Jesus first (despite what politicians—many of whom have a messiah-complex, might hope for). Nor is our call to place ourselves first. It’s a call to follow Jesus and put our total trust in him. It means we must obey the first commandment: to have no god other than the one true God. It means to take seriously the great commandment: to love God—the God revealed in Jesus Christ—with all our hearts and souls and minds and strength.

If we are grounded in our love for God as revealed in Jesus Christ, we will be able to fearlessly pick up our crosses, whatever form it may take, when Jesus calls. This means following Jesus even if it means losing our friends or being alienated from our families. This means following Jesus even though we will be despised. And it means we must be willing to follow Jesus even if lose our lives. We follow Jesus, and only him. Jesus is all that matters. Amen.

©2020

[1] 1 Corinthians 1:18

[2] See John 8:32-36.

[3] Matthew 16”24-28, Mark 8:34-9:1 and Luke 9:23-27. In each of these gospels, this scene is followed by the Transfiguration. Only Mark has the previous story of Peter confessing Jesus to be the Messiah.

[4] John 18:10.

[5] Romans 8:13.

[6] See Hebrews 10:1-18.

[7] 1 Corinthians 15:56.

Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012), 712 pages including notes and sources and 32 inserted pages of black and white photos.

Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012), 712 pages including notes and sources and 32 inserted pages of black and white photos. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison David Lee, Mine Tailings (Boulder, UT: Five Sisters Press, 2019), 79 pages.

David Lee, Mine Tailings (Boulder, UT: Five Sisters Press, 2019), 79 pages.

James H. Cone, (Marynoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 202 pages including notes and an index.

James H. Cone, (Marynoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 202 pages including notes and an index.