In 2013, I visited Virginia City, Nevada. I had lived there in the 1980s, when I was a student pastor at First Presbyterian Church. Before my time there, a tourist railroad had been established and was reconstructing the famed Virginia and Truckee Railroad. The big news when I was there, was the train crossing the highway into Gold Hill. Since then, thanks to generous grants, the train now runs to the outskirts of Carson City. It is a crooked grade as the train climbs up the east flank of the Virginia Mountains. I wanted to ride this train and see what it was like in earlier days. But they had sold out of the tickets for the weekend I was to be in Virginia City. Telling this to a friend who at the time was also the bookkeeper for the railroad, she said she’d make a call and see what she could do. When I got to town, she asked if I’d like to ride in the cab of the train. Of course, I would! It was the ride of a lifetime. I wrote this piece almost ten years ago and have polished it up a bit for posting here.

I arrive at the V&T shops a little after 7 AM. As they prepare the engine ready for the day’s run, I walk around the machine shop where the Virginia and Truckee has the capability of repairing and rebuilding old locomotives. Maintaining a steam locomotive requires a lot of work and a shop is a necessity as parts often have to be fashioned to replace those that have worn out. The complexity of a steam engine led to their demise as it is much easier to maintain diesel-electric locomotives. Today’s locomotives may be efficient and easier to maintain, but they lack the romance and the “life-like character” of a “breathing steam engine.”

Our run today is aboard a ninety-ton Baldwin locomotive built in 1914 for a logging operation. The locomotive features smaller wheels and a large boiler, which also made it a perfect engine to pull trains up a steep line that snakes around the Virginia Range as it climbs from the Carson River to Virginia City. In its “working life,” this locomotive hauled logs for the McCloud Logging Railroad which ran around Mt. Shasta in Northern California. Today, she hauls tourists to the Comstock Lode and has been trucked offsite (she is the largest locomotive capable of being trucked) for movie appearances. Some of the guys from the V&T ran her in the movie, “Water for Elephants,” and have a photo in the shop with Reese Witherspoon, one of the stars in the film.

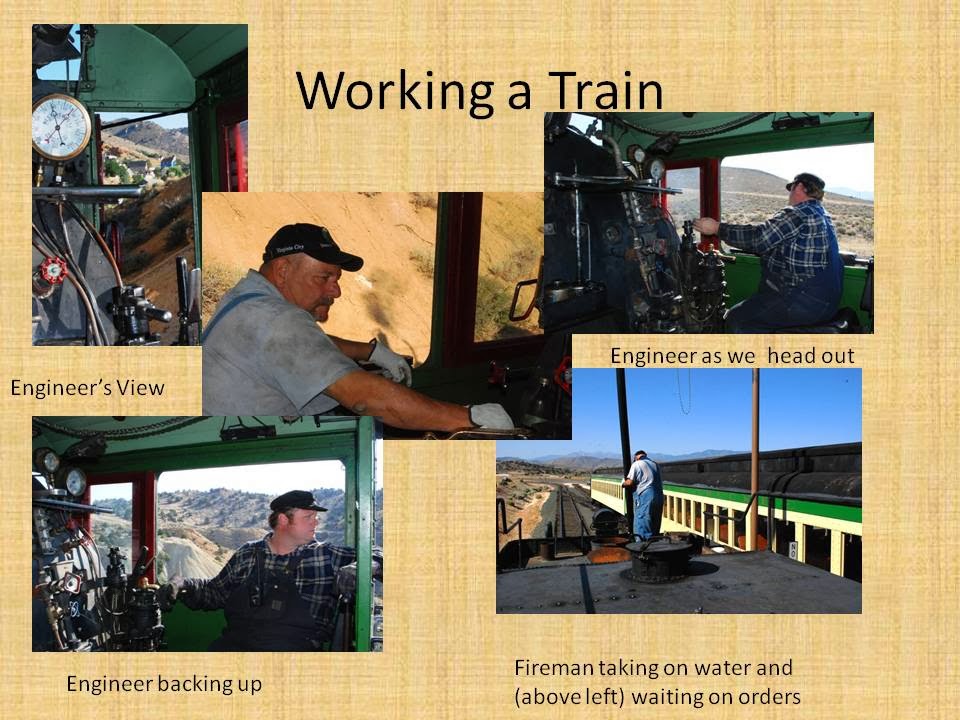

At about 7:30, Tim, who serves as conductor and brakeman, tells me to hope aboard. He introduces me to the crew, Brian and Ed, and gives me some instructions such as watching my feet so that I don’t ruin my shoes or injure myself by being pinched by rotating the sheet metal flooring between the tender and the locomotive. While we wait for the signal, the iron horse hisses. A few times every minute, there’s a booming sound which I learn are the air pumps keeping a nice draft in the fire box. When we get the “all clear,” I find a comfortable place to stand and hold on as Brian, the engineer moves the throttle into position and releases the brakes. We’re off, pulling three empty passenger cars. Because there is no longer a working turntable, we’ll pull the cars down the grade with the tender in the lead. At Moundhouse (Carson Eastgate), where we’ll pick up passengers, we can drop the cars, move the engine to the front as in a normal train, and the pull the cars back up hill.

It’s cool in the morning, but it promises to be a warm day. Because the grade steepness, the descent must be controlled. I watch Ed, the fireman, as he maintains the boiler, making sure there is enough steam for both movement and brakes. Ed learned to fire a locomotive on a miniature (5 ton) steam trains in California. Brian jokes that he has the easy job and Ed agrees. Oil fires this locomotive. Coal would require shoveling, but the fireman is free of that task. However, watching the boiller requires constant vigilance, especially on a grade like the V&T which has a few places that you might be going down, only to find yourself heading uphill for a short stretch. Besides keeping enough steam so that Brian can operate the train, he must make sure the water level remains high enough to cover the plates within the boiler. On level ground, this is easy, but when the locomotive is pointed uphill, the water runs into the back of the boiler. When it goes over a hump and points downhill, the water moves to the front of the locomotive. The danger of this sloshing around is that the metal might be exposed to air and the fire without the water to cool it down. This would risk spraying those of us in the cab with steam and seriously damaging the boiler.

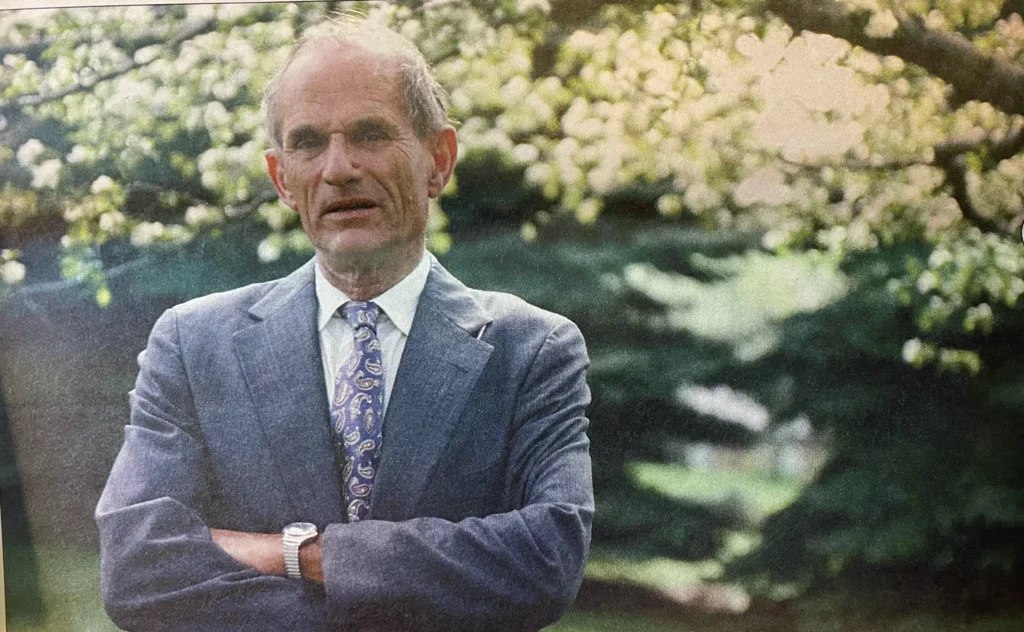

Brian, our engineer for the day, oversees the train itself. He’s a Virginia City native. He graduated from high school on the Comstock in 2000 and that summer went to work for the railroad. He’s been at it ever since. For years, he was seasonal and had to find other employment in the winter, but a few years ago, was hired on full time. In the winter, they make a few runs (last year’s Christmas run was infamous as the snow was heavy and it took them nearly three hours to make the run back up the mountain. Brian and Ed can do each other’s jobs and often switch back and forth. As the engineer, he’s in charge of the operation of the train, but must depend on the fireman to watch the boiler and to provide him the steam needed for a smooth operation.

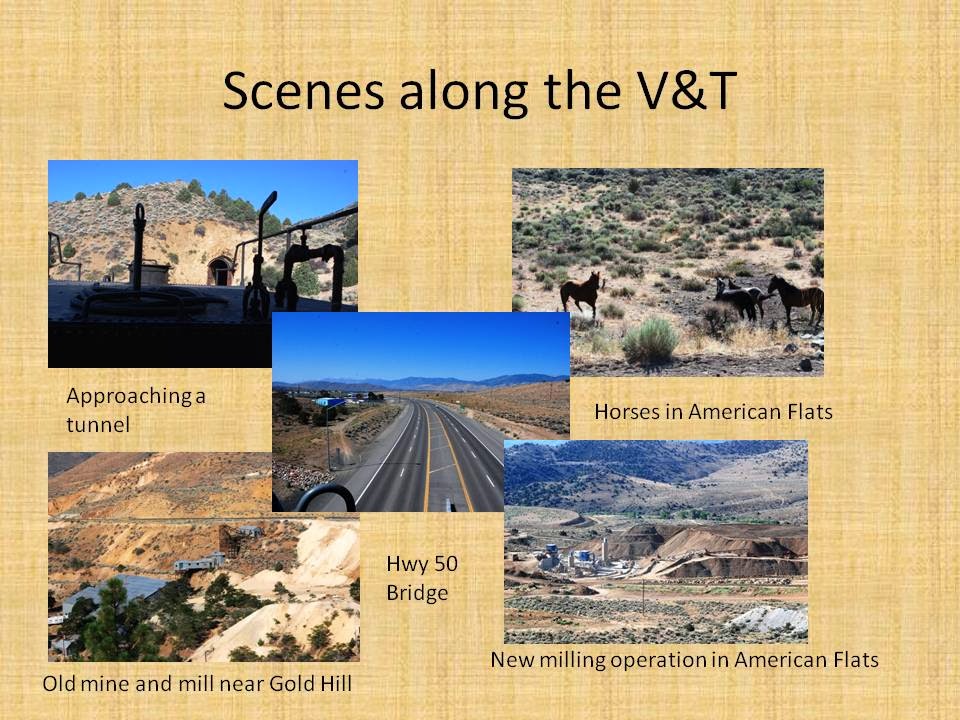

A few minutes later, Virginia City is out of sight as we cross the tunnel at the Divide and move toward Gold Hill. Down below us is the Crown Point Mine and Mill site. We cross the highway, by the old station. then the tracks turn south and cross earth fill that once traversed by the Crown Point trestle. They tore the trestle down in 1936. Today, it is widely believed that the trestle continues to live on the Nevada State Seal. However, this is a myth. The seal was designed in 1863 and predates the building of the trestle by five years. Interestingly, there wasn’t even a train within the boundaries of the Nevada Territory when the seal was designed, so the trestle on the seal expressed a hopeful dream of the artist.

After Gold Hill, the tracks make a long circle around American Flats. There is a new mining operation with cyanide leach fields on the north side of the Flats. Also along this section is a herd of horses. Ed and Brian seem to know well as they have names for many of the wild animals. At Scales siding, the halfway point, we stop, and Brain and Tim check the brakes. There is some smoke in one wheel and they are afraid it is overheating, but after checking it, all appears well. We loop around the south side of the Flats, above the old American Flats Mill, which operated up into the 30s. Then the tracks turn south, and we slip into a tunnel. On the other side of the tunnel, we can see Moundhouse, the site of where the Virginia and Truckee and the Carson and Colorado Narrow Gauge used to connect. The train continues to hug the hillside. The tracks mostly follow the original route except through Moundhouse. Brain, the engineer, tells me that the original tracks went straight through Moundhouse and picked up the Carson River near where today are several brothels. Figuring the whorehouses shouldn’t be disturbed by trains, they relocate the tracks to the west of town. We cross over Highway 50 on a trestle and soon are at the station.

A full parking lot awaits us as people line up to ride a piece of history. We drop the passenger cars in front of the depot and uncouple the engine. Switching tracks, we take on water. I learn that although the train will only use 300 gallons of oil during the weekend, each trip up and down the mountain will require nearly 8000 gallons of water. Once they fill the water take, we run through a wye and then pull in front front of the passenger cars for the run up the mountain. Before leaving, Brian oils the working parts of the locomotive

As we leave Moundhouse, Ed pours a couple of cans of sand into the firebox. The draft is such that the sand is sucked through the boiler tubes and out the stack, cleaning out any build up on the tubes and hopefully making the train run smoother. As the sand runs through the boiler, or perhaps because of the addition air of having the firebox open, the smoke turns black for a few minutes. Although it was a relaxed trip going down the mountain, running uphill requires more work, especially from Ed, who has to constantly keep checking on the boiler and making sure there is enough steam for running the train. It almost seems he is as much of an artist as a mechanic as he both watches the gauges and adjusts the amount of water going into the boiler or the amount of fuel pumped into the firebox. But it’s not just the gages that he watches; he also keeps an eye on the smoke, occasionally glances into the firebox, and is always listening to the boiler breathing.

The sun is now high in the sky and it’s getting hot, but I’m not prepared for the experience of the first tunnel. When we enter it, a hot wind blows across the boiler and into the cab and the temperature must have risen by 30 or 40 degrees. Coming down, with the boiler behind us, the tunnels weren’t hot, but with the boiler in front, we feel all the heat. This was the reason the last steam engines built for the Southern Pacific were “cab-forward” varieties. It was harder to build a cab-forward locomotive when the fireman had to shovel coal (or you had to have the fireman and engineer in two different ends of the train which created communication problems). But once the railroad began using oil, they could move both to the front of the boiler. Not only did this allow better views of the track, it keep the cab more comfortable in long tunnels and the miles and miles of snowsheds the locomotives traveled as they made their way through the Sierras.

At Scales, we stop for a few minutes and Brian gets out and oils various parts of the engine. We then continue on until the Gold Hill Station where a few people get off in order to have lunch at the Gold Hill Hotel. Most of our passengers continue as the train climbs into Virginia City. There, everyone gets off. They’ll have three hours to tour the town before making the run back south. I skip the ride south but follow the train in my car. Stepping out into the heat, I photograph the train repeatedly as it makes its way down the mountain. Ed, Brian and Tim will leave the train at Moundhouse overnight. The next morning they’ll pick up passengers and run them up to Virginia City. At the end of the day, after dropping the passengers off in Moundhouse, the empty train will be driven back up the mountain to Virginia City. There, it will shuttle tourists around the Comstock between Virginia City and Gold Hill. The steam trains only run between Moundhouse and Virginia City on Saturdays and Sundays.