Jeff Garrison

Bluemont and Mayberry Churches

October 28, 2023

2 Corinthians 11:16-33

At the beginning of worship:

Ad hominem is a Latin term that translates as “to the person.” It refers to a common fallacy in which, instead of attacking someone’s idea, the attacker makes a personal attack. Sadly, we see it all the time in politics. It’s often used as a red herring, another form of a fallacy, where instead of challenging another’s proposals, you dangle something else out such as their education, character, religion, morals, or background. These often have nothing to do with the idea in question. In today’s scripture, we’ll see Paul has been the subject of ad hominem attack and how he responds.

Before reading the scripture:

We’re continuing our work through Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians, Last week we began looking at Paul’s “Fool’s Speech.” We’re continuing through this “speech,” this week. This section of the letter, which takes up chapters 11 and 12, received such a title because Paul continually refers to himself as a fool.

Paul uses variations of the word fool almost twice as many times in his letter to the Corinthians than he does in the rest of his letters.[1]

Paul plays the fool to show the foolishness of the Corinthians and of those who followed him into the city and preached a different gospel. Paul utilizes parody to combat those who would change the gospel.[2]

Paul goes on offense against those who have made disparaging remarks about him. Paul knows boasting, outside of boasting of Christ, is unbecoming of a Christian. But because of the attacks on his character, he reluctantly responds.[3] Also, as we have seen over the past couple of weeks, we gain more insight into Paul, the person. From today’s reading. I think Paul might have enjoyed Gary Larson’s “Far Side” comic strips.

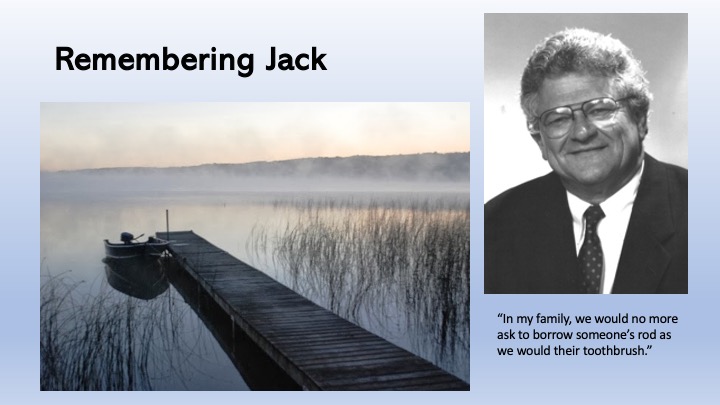

Most ministers, I’m including myself, experience someone who follows you in a church with an idea with which you don’t fully agree. In our system of church government, where you’re not supposed to be involved in church politics once you leave a call, you must (or at least you should) bite your lip and let go.

(But I can tell you, can’t I? Hopefully none from my former church are listening in today…)

The church in Cedar City, Utah will always have a special place in my heart. I served there for a decade. The church grew and I helped relocate and build the first new church building in my ministry.[4] The new church sanctuary, which ain’t so new anymore as they celebrated 25 years in the new church a year ago, had clear glass windows. From one side, you could look up at unique rock formation of Fiddler’s Canyon. The other side looked out across the valley toward Lund. Both sights were beautiful. The church itself was stucco, which fit in the desert southwest.

When I was a pastor, a few people expressed the desire the church might become wealthy enough to purchase stained glass windows. I disagreed. I was rather vocal that such windows only belong in stone or brick churches. Besides, I suggested, why would you want to cover up the beauty of God’s creation.

Probably ten years after I left, someone came along and wrote a check for the purchase of stained-glass windows. I bit a hole in my cheek when visiting as they showed off the windows and bragged on their beauty. The damage had already been done. There wasn’t anything I could do about it. “That’s nice,” I mumbled.

That said, I’m sure when I’m retired and gone, y’all do something I won’t like and I’ll have to smile, shake my head, and say something non-committal such as, “that’s nice.” Of course, we’d all do well to remember that church isn’t about us. It’s about Christ.

But Paul didn’t have to abide by Presbyterian polity. There were no Committee on Ministries in the first century to slap his hands and say he was out of bounds. But then, he felt responsible for the church in Corinth and tried to help it navigate the temptations of the day. Last week, I suggested that these new missionaries may be teaching about Jesus’ life, but avoiding the key to Christian faith, his death and resurrection.

My reason for suggesting that these were Jewish “lite-Christians” comes from this section. We learn they have a Jewish background. Jesus’ teachings were not out-of-line for the rabbis of the day. The scandalous part of the early Christian beliefs were the manner of Jesus’ death and his resurrection. But for Paul and us, that’s the crux of the gospel.

Paul begins our reading this morning by returning to where he was in verse 1 of this chapter. He reverts to being foolish and asking the Corinthians to bear with him. Interestingly, he says this isn’t the Lord’s teachings, but he’s lowering himself to the level of those boasting missionaries who have followed him in Corinth. And he sarcastically snipes at the Corinthians for gladly putting up with fools.

These “fools,” Paul says in the 20th verse, makes them slaves. With this, Paul refers to the slavery of the law as opposed to the freedom of the gospel. He also suggests the “fools” prey upon them, refer to their demand for payment, as we saw last week.

Paul concludes the first paragraph with the suggestion that “we” (him and the Corinthians) are too weak for that. If you remember, Paul began his first letter to the Corinthians speaking of how God uses human weakness to bring shame on human wisdom. So, both Paul and the Corinthians, need to play dumb and depend on God and not their own wit.[5]

In our second paragraph, beginning with the second half of verse 21, Paul goes all out with his “fools’ speech.” [6] He examines the boasting of those who are challenging his authority. Paul either meets or tops their challenge.

They say they are a Hebrew, so is he. They say they are Israelites, so is he. Likewise, he’s also a son of Abraham. These three challenges all have to do with his Jewish identity. To us, they sound similar, but by saying he’s Hebrew, Paul probably refers to the fact he can read Hebrew. As an Israelite, he follows of God.[7]As a child of Abraham, he is not a proselyte to the faith, but a birth member of the tribe.

Next, Paul goes into the Christian faith. These outsiders say they are ministers of Christ, but Paul insists he’s a better one. Now Paul begins to brag on what he’s endured for Christ. Paul’s life hasn’t been easy. It’s one of hardship as he’s had more imprisonments than these impostors. The he refers to the floggings he’s received, which came from the Jewish authorities. The forty lashes minus one are a punishment outlined in the Old Testament. Paul has also received beatings with rods, which were a Roman-styled punishment.[8] He’s been stoned.

If Paul had not believed in the truth of Christ, why would he put up with this abuse?

Paul then goes into the more natural challenges he’s faced. He’s been shipwrecked. He drifted for a day waiting to be rescued, which implies him holding on to a piece of the ship that floated. He’s faced dangers from rivers and bandits and dangerous people. He’s spent sleepless and cold nights, been hungry and thirsty. Finally, he worries insentiently about the churches he established.[9]

Jesus suffered in his life, as did Paul. In his bragging, he shows himself to be superior to these missionaries who speak of a limited gospel while living off the offerings upon whom they prey. Essentially, Paul is asking the Corinthians if they think these so-called missionaries could endure what he has endured.

Paul concludes this section of his speech proclaiming that his boasting shows his weakness. Paul could only endure what he experienced with God’s help. He insists, before God, that he has not lied. Then, almost as he forgotten, he adds that incident early in his Christian life, where he was let down the wall to escape Damascus.[10]

While it is natural for us to place ourselves in the role of Paul to see what we might learn from this passage, I want us to try something else. How about seeing ourselves as the Corinthians who read this letter. Paul, in this passage, by playing the fool, isn’t really attacking those who talked trash about him. Paul flips from the wayward missionaries being fools, and points to the foolishness of the Corinthians.[11] They have listened and are accepting this false gospel.

We are constantly lured away by what’s shiny and new. That’s the purpose of advertising, to sell us the “new and improved.” But when it comes to our faith, we’re best to stick to the “tried and true.” As the Heidelberg Catechism begins, “Our only comfort in life and death is that I am not my own, but belong—body and soul, in life and in death—to my faithful Savior, Jesus Christ.[12] Amen.

[1] Paul uses variations of fool 11 times in 1st Corinthians and 7 times in 2 Corinthians. He uses it 5 times in Romans, twice in Galatians and only once in Ephesians, 1 Timothy, and Titus.

[2] Paul Barnett, The Second Epistle to the Corinthians (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1997), 528,

[3] Ernest Best, Second Corinthians: Interpretation, a Biblical Commentary for Teaching and Preaching, (Louisville, KY: JKP, 1987). 109. See also 2 Corinthians 10:17f.

[4] I served Community Presbyterian Church of Cedar City from October 1993 to January 2004. We moved into the new church building in December 1997.

[5] 1 Corinthians 1:20-25.

[6] Barnet see’s the “fools’ speech proper beginning with verse 21b. Barnett, 534.

[7] The world “Israel” means the one who struggles with God. See Genesis 32:28.

[8] See Deuteronomy 25:2-4. See also C. K. Barrett, A Commentary on the Second Epistle to the Corinthians (1973, Hendrickson Publishing, 1987), 296-297.

[9] Acts only tells us of one shipwreck (Acts 27:13-44). However, this shipwreck doesn’t fit the timeline for 2 Corinthians. While we hear of Paul suffering beatings and stoning (Acts 16:23-24, 21:31-32, 22:23-36, 23:9-10), most of these events are not mentioned in the New Testament. See Barrett, 267-300.

[10] Acts 9:23-25. There is a slight difference from this story and the one told in Acts. Here, Paul makes it sound as if those watching the city were the authorities under the king, while in Acts we’re told it is the Jews.

[11] Barnett, 532.

[12] Presbyterian Church USA, Book of Confessions, “The Heidelberg Catechism” 4.001.