Delia Owens, Where the Crawdads Sing

(New York: G. P. Putman and Sons, 2018), 372 pages.

Kya Clark, “the Marsh Girl” lives in the salt marsh of Eastern North Carolina. As a child, her mother abandons the family. Then one by one, her siblings’ leaves. Finally, her father, the one who has run everyone else off, leaves. Abandoned by everyone who should have cared for her, she learns how to survive. She digs shellfish and sells them to Jumpin, an old African American who sells gas and bait along the marsh. Jumpin and his wife Mabel, in a way, become surrogate parents for Kaya. She gets by, eating what she collects along with making enough money to buy cornmeal and oil in town.

Kya only spent one day in the school. Picked on by other children, she never went back, always staying one step ahead of the truancy officer. She befriends Tate, a former friend of one of her brothers. Over time, Tate teaches her to read and begins to lend her books which allows her to learn more about the marsh. But he, too, leaves as he heads to Chapel Hill for college. He fails to come back as promised. Only later, does he come back and try to re-establish contact as he establishes a nearby research lab on the marsh. Kya, who had taken up painting, becomes a self-taught an expert in marsh ecology. She even publishing books based on her paintings.

While feeling abandoned by Tate, Chase, another town boy seeks out Kya. Primarily interested in sex, Chase promises to marry her and build her a house. Then Kya learns through the newspaper of his engagement to another woman. Later, in 1969, Chase ends up dead, having fallen from a fire tower. It’s not clear if foul play is involved, but Chase’s mother points the finger at Kya. Eventually, the sheriff on sketchy evidence, arrests Kya. Tried for murder, she’s found not guilty.

After this ordeal, Kya and Tate get back together, living in the marsh until Kya dies from a heart attack in her 60s. Afterwards, Tate discovers Kya’s secret, which he had not suspected.

Owen captures the beauty and diversity of the marsh. The reader also feels empathy for Kya, someone who has fallen through the cracks. While alone, she develops resilience but is unable to trust anyone else. Only later, at her trial, do we learn there were those in the town who tried to help her, such as the woman at the grocery story who would give her back more change than was due, taking the money out of her own pocket.

This an enjoyable read. I recommend this book. Having grown up near the marsh in North Carolina, this book helped take me back to a time the marsh wasn’t overgrown with housing.

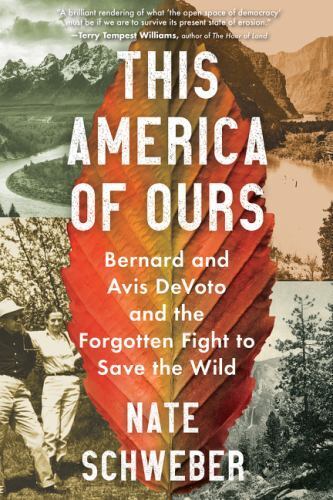

Bernard DeVoto, The Hour: A Cocktail Manifesto

(1948, Portland OR, Tin House Books, 2010), 127 pages.

For the past few years, I have avoided alcohol during most of January, at least when I been at home. But I break my fast on the 25th, to celebrate the birth of the Scottish bard, Robert Burns, with a shot of “Balvenie” and the reading of a few poems. So, why I chose to read a book about the cocktail hour during January is beyond me. But so far, I managed to keep the fast. Instead of placing this book in a bookcase, I have stored it in my liquor cabinet. For like a good Scotch whisky, one should savor this book..

Bernard DeVoto died two years before my birth. But as a some-times 19th Century Western American historian myself, I have been familiar with his work for nearly forty years. Decades ago, I read a couple of his classics: Year of Decision, and Mark Twain’s America. Both were serious works, although one can’t deal with Twain without enjoying a good joke. Last year I read This America of Ours, a biography of DeVoto and his wife Avis. From that biography, I learned of this little book. Much of the book had me laughing out loud. DeVoto precision details about the making of a good martini ranks up there with George Orwell’s essay on how to make a proper cup of tea. I wonder if perhaps Orwell might have inspired DeVoto as his essay appeared two years before DeVoto copyrighted his work.

DeVoto and his wife were known for their cocktail parties. Much of what makes this short book so funny is DeVoto’s seriousness. It’s his way or the highway. Those who disagree with him, from his perspective, deserve some terrible fate.

In the opening essay, DeVoto praises America’s greatness for we have “enriched civilization with rye, bourbon, and the martini cocktail.” He also praises Scotch and Irish whiskeys alongside of bourbon and rye, insist they consumed straight. He had no use for rum and was willing to damn to hell those who abided in the nasty drink. However, as a historian, he knew rum’s role in American’s history and acknowledges how rum played a role in our freedom and in the institution of slavery. Had the sailor’s “primordial capitalist bosses not given them rum, [they] would have done something to get their wages raised.”

The second chapter begins with an assault on recipes for various cocktails found in cookbooks and women’s magazines. In DeVoto’s world, these are all unnecessary, for one either drank whiskey or a martini. Pity the poor man who would allow vermouth and whiskey to meet for “the Manhattan is an offense against piety.” Of course, vermouth is used with gin to make a martini. In DeVoto’s world, it better be dry vermouth. And don’t get cute with your drinks. He bemoaned a bar in Chicago which offered “Whiskey on the Barney Stone.” They used green colored ice. DeVoto suggested the proprietor be “put to the torture.” In a later chapter, he goes after the couple who has all kinds of fancy drinking kitsch such as stoppers featuring women’s legs, fancy stirring rods, and signs about drinking. DeVoto had no patience with such foolishness, but then they were probably making daiquiris.

Long before James Bond, DeVoto suggested it didn’t matter if one shook or stirred the martini. What mattered, however, was avoiding splinters of ice in the drink. Each round of martinis is to be made fresh. There can be no salvation for the man who makes pitchers of martinis and stores them in the refrigerator. Those who desire an olive in their drink were probably denied a pickle in their childhood which sent them on a lifelong quest for brine. As for those who want an onion, “strangulation seems best.”

The only thing one might mix in with whiskey are bitters, but then only Angostura bitters. And no fruit salads. The fruit from orchards do not belong in cocktails. Drinks should be served cold. I’m not sure what DeVoto thought about Japanese sake, which is usually served warm. Writing in the aftermath of the war, he probably thought it justified the use of the bomb.

In the third chapter, DeVoto attacks the enemy of drinks—sugar. He believes the reason too many people want sugary drinks is that we give our children too much sugar. “An ice cream soda can set a child’s feet in the path that ends in grenadine…” While such drinkers are to be pitied, they should also be treated as “a carrier of typhoid.” DeVoto even prophesizes the demise of our Republic will most likely come for “this lust for sweet drinks.” And sugar comes from other sources, not just crystals. Fruit has no place during the cocktail hour. DeVoto suggests “orange bitters make a good astringent for the face,” but they don’t belong in drinks.

I did take a bit of offense at DeVoto’s attack on winter drinks. He has no use for eggnog or a Tom and Jerry. I assume If he hears I occasionally like a hot butter rum after spending time outdoors on a cold snowy day, he’d roll in his grave. But then, that’s a ski drink, and DeVoto didn’t care for the sport.

I wish I had read this book 25 years ago. Two friends of mine from Utah, both now deceased, would have enjoyed it. Or maybe just one of them. Ralph insisted on making his and his wife’s martini, one at a time. Thankfully, he always had some good peaty Scotch to offer me. Myron, however, might have taken offense. Myron was one of those martini drinkers who made the drink by the pitcher and stored it in the fridge. DeVoto would have had a cow had he witnessed Myron pouring himself a martini from a pitcher he mixed three days earlier. But I never blamed Myron, for he always offered me a pour from a bottle of Glenmorangie

Obviously, while I have never cared for martinis, I enjoyed this book. If you want a martini, that’s fine. Just offer me some converted rye, corn, or barley, aged in a white oak barrel. Ice would be nice, as long as it’s not green.

Sarah Frey, The Growing Season: How I Built a New Life-and Saved an American Farm

(Audible, 2020), 8 hours and 41 minutes.

In a way, this book reminded me of Stephanie Stuckey’s book which I read last year. Both are women executives leading major companies. But that’s where the comparison stops. Stuckey came from a well-to-do family. She took over her family’s business as it was about to completely go under and lead back to thriving. However, Frey came from a very modest background and built a major business.

In this book, Frey describes her childhood on “the hill,” a small farm in southern Illinois. Her dad, who had ties to horse racing, always wanted to have a winning horse and sunk all the money the family was able to provide into his beloved horses. While he doted on his daughter, he could be mean. This was especially true tohis sons and wife. He also had another family before setting out with Sarah’s mother, which gave Sarah and her brothers a huge family of stepbrothers and sisters. Yet, for all his faults, he instilled in his daughter a belief she could do anything.

As Sarah grew older, and her older brothers began to move out on their own, the family began to collapse. Still in high school, Sarah moved out on her own and continued to work and attend school. Having watched her mother buy watermelons for local farmers and sell them to supermarkets, she tries it on her own. Soon, she was borrowing money from a bank for a larger truck. Her business thrived and after two months was able to pay off the truck. She would continue expanding, adding pumpkins to extend her season. Soon, she realized that she should also start raising some of the produce to provide better returns. When the bank took over her father’s farm, she went back to the banker who’d lent the money for the truck. He. helped arrange the purchase of the property from the bank which held the title.

Then, as a nearby Walmart distribution center opens, she talks the produce buyer to let her provide watermelons and pumpkins. She readily agreed she could supply them the four loads a week, thinking of her normal load and not four loaded tractor trailers. Realizing she was about to get in over her head, she gave a call to her brother. Soon, she has all her brothers working with her.

In time her business expanded and included not just Walmart, but most major grocery stores. She also began producing drinks made of vegetable and fruit juices. In telling the story, lots of things seem to be left out (such as financing and attorneys). Throughout the book, but especially at the end, she continued to hit several key points. These include giving people a chancl, treating employees and customers right, hiring those with potential whom others over look, and being creative such as using that usually left in the field for other products. While a lot of the book focuses on herself, she always offers thanks to those who helped her along the way.

Frey is also frank about her husband. And while the marriage didn’t work out, it gave her two boys whom she now tries to spend more time with.

While I felt a lot of details were missing, I enjoyed this book. It’s a fast read/listen.

John Musgrave, The Education of Corporal John Musgrave

2021, Random House Audio, 9 hours and 38 minutes

He always wanted to be a Marine. At the age of 17, John Musgrave signed up with the Corp, having his parents sign for permission. The summer after graduation, he left the Midwest with a couple of friends for the Marine Corp training facility in Southern California. The experience nearly killed him, metaphorically. He describes the experience the rude awakening once they arrived by train to graduation. But he endured and became a proud Marine. This was 1966 and, after advance training, he headed to Vietnam.

At first, Musgrave was excited about the war. They sailed from California to Vietnam on a troop ship. He was first assigned to an MP group in the southern part of the country, but wanting more action, volunteered for a transfer. The transfer landed him just south of the DMZ, a unit known as the Walking Dead, as they were taking so many casualties. He complained when military took away his M14 and gave them all M16, with just one cleaning kit per squad and how they gun so often jammed, which lead to many dead Marines.

Musgrave writes with honesty, as he had done with his boot camp experiences. He tells about his first enemy kill. He discusses the hardship of slipping through the wire to conduct night patrols. He’s honest about how scared they were, in the dark jungle where one not only had to deal with the enemy but mosquitoes and leeches.

Twice wounded, the second time he took a bullet in the chest. No one thought he would make it, even some of the doctors who treated him. But one surgeon didn’t give up. Eventually, he is stabilized and moved out of the country to better facilities in Japan before moving back to the States. He’d spent 11 months in country.

Throughout the first half of the book, Musgrave shares personal struggles. Although his father served in World War 2, he and his mother continued to worry about him being in the Corp. He was in love with a girl from his high school and wanted to get married, but she broke off their relationship. He is also very honest about his religious feelings. As a Methodist, a Catholic neighbor had given him a St. Christopher’s medallion which he carried wore on his dog tags. The medallion causes him to be superstitious, thinking that if he keeps it, it will protect him. However, the day he was wounded a second time, he had a premonition he would die that day. While he lived, it was a close call.

Arriving back in the states, Musgrave discovered things were different. The anti-war movement was just beginning. At first, Musgrave didn’t want anything to do with it as he began college. But soon agreed that the war was a mistake and began to speak out. He became a leader in the Vietnam Vets Against the War movement and even helped led the protests in Miami during the Republican National Convention in 1972.

While Musgrave eventually became a leader of the movement, he continued to work to bring Vietnam Veterans together. He is critical of how Vietnam Veterans were not welcome in American Legion and Veterans of Foreign War posts. Through this, he struggles with his pride at having been a Marine and the guilt of having fought an unjust war. As our nation experienced other wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, he worked with veterans, helping them cope as they returned home.

I enjoyed the book. Growing up watching the news every night at the dinner table, the Vietnam War was always very real. I knew lots of veterans and wondered if it was in my future. Thankfully, we pulled out of the war when I was a sophomore in high school. As I was preparing for graduation, Saigon fell and the war was over.