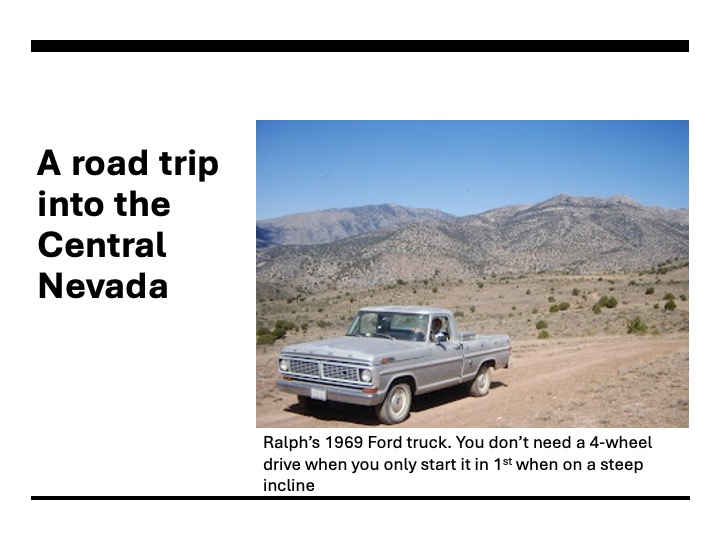

This was a trip I made with a friend from Cedar City in the late 1990s. I wrote this piece for another blog about 15 years ago, around the time of Ralph’s death. I bring it back out because in last Sunday’s sermon, I mentioned this trip. I have updated the writing a bit. I should go back through my slides and pick out more to feature (or maybe add a map of our travels).

Camping on Main Street, Treasure City

“This street used to be bustling with noise,” I think, as I stroll down Main Street, Treasure City. The sounds of wagons and the clicking hooves from horses, added to the cussing of teamsters, the pounding of stamp mills and the music from saloons would have too much. But I swear I can still hear voices in the brisk wind, bringing a chill the summer air. My belly is full. Ralph and I had just eaten a steak and a baked potato, along with a salad. We’d drown it with a beer. Before hitting the sack, I decide to walk the length of the road. Ralph stays behind to tend the fire. The distant mountains are turning purple. This street had once a thriving business district with forty stores and a dozen saloons, but today just the shells of collapsing rock structures remain.

By the time I get back to the truck, Ralph has let the fire die down and is already in his sleeping bag. I blow up my mattress and rolled my bag out on the other side of the truck. Plopping down, I watch the summer stars and listen to the wind and Ralph’s snoring. Soon, I too am asleep. I wake at first light. The wind has died and silence seems eerie. While the coffee perks, I explore some nearby ruins. The evening before, I stayed on the gravel road for the mountain is pitted with mine shafts. A wrong step could send you several hundred feet down and into oblivion.

History of the mining region

In the later part of the 1860s, miners from Austin and the Reese River Mining District in search of another mother lode discovered rich in what became the White Pine Mining District. One of the first discoveries, in 1865, was named Monte Christo. It’s just a few miles west of here. From there, miners set out in all directions and in 1867, discovered what became known as Treasure Hill, the mountain upon which we’d camped. The land was unforgiving. There was little shade in the summer and an altitude above 8,000 feet created brutal winters. But with some of the ore as pure silver chloride and assayed as high as $15,000 a ton, people were willing to put up with the hardships.

By 1869, Treasure City with a population of 6,000 had been established on top of the mountain. There were nearly 200 mines along with ten mills to crush the ore into powder, in preparation to leaching out the silver and gold. A water company laid pipe and had the ability to pump 60,000 gallons a day to the top of the thirsty mountain. But it was all short lived. Most mines played out after a few hundred feet and the rock proved a formable challenge. Early in 1870, the excitement began to wane. By the end of 1870, only 500 people remained. In 1880, when the Post Office closed, there were only 24 people left living on the mountain.

Economic lessons for the region

A look at Treasure Hill’s rise and fall provides an economic lesson in the danger of speculation and bubbles and international finance. Western Historian W. Turrentine Jackson, in his classic study on the region, Treasure Hill, goes into great detail of the financing of the district. In the late 1860s, so much money was poured into the region, more than was ever needed to develop the mines. Much of this capital was wasted; some of it spent on bogus mining operations that existed only to mine the pockets of capitalists who hoped to make a fortune and were willing to take great risks. Then, as the availability of high grade ore begin to wane, money begin to be withdrawn from the region. John Muir visited the area after the rush and wrote in Steep Trails:

“Many of [the mines] do not represent any good accomplishment and have no right to be. They are monuments of fraud and ignorance—sin against science. The drifts and tunnels in the rocks may be regarded as the prayers of the prospectors offered for the wealth he so earnestly craves; but like prayers of any kind not in harmony with nature, they are unanswered.” (Elliott, 105)

Leaving Cedar City

Ralph and I got an early start for this remote spot in the Nevada desert. Leaving Cedar City, we drive north to Minersville and then on to Milford, where we cross the Union Pacific tracks and set out across the desert on Utah 130. Our travels take us just south of the ghost town of Frisco and north of the Wah Wah Mountains. We enter Nevada at Baker. Shortly after meeting up with Highway 50, we leave the pavement for a rough road that skirts the north boundary of Great Basin National Park.

Osceola

Our first stop is at the site of Osceola. Here, In 1872, a unique mining community for Nevada existed. Hard rock mining is the norm in Nevada. This was industrial mining. Miners dig shafts and drifts as they blast into rock for ore. The ore was then crushed and chemically treated to extract the metals. However, in Osceola, free ore existed in sediment. Placer mining, as was done in the California gold fields, was possible. All one needed were shovels and pans, some water, and perhaps a sluice box. The difficulty with placer mining here was the lack of water. Early in the town’s history, they dug a ditch up Wheeler Peak to divert water to the town. This mining district boasts the largest gold nugget ever found in Nevada. There is not much left of the town that existed here for nearly fifty years. Fires, the bane of mining camps, sent most of the town up into smoke. Modern mining operations destroyed the rest. Only the graveyard and some mining equipment used more recently remains.Interestingly, even with gold near historic lows (this was in the late-90s), there’s still a few people mining in this district.

Ely

Leaving the cemetery behind, we drive out of the canyon and head west, across an alluvial fan and toward the highway. Reconnecting to US 50, we continue on to Ely where we stop and have lunch at the historic Hotel Nevada. I suggest we eat on the road to make better time, but Ralph cringes. “If I can’t sit down and enjoy my meal, I’m not living right,” he insists. After lunch, we continue west on US 50, passing the huge open pit copper mine at Ruth and thirty minutes later, the Illipah Ranch. Somewhere between Ely and Eureka, we abandon the pavement and head south on a gravel road.

Hamilton

Hamilton is our first stop, nine miles south of US 50. It sits on the north side of Treasure Hill and served as a logistical point for the various mining communities south of here. The town was first called Cave City as so many miners from the mountains sought refuge there in caves during the harsh winters. As mining flourished, they laid out a town. By the spring of 1869, more than 10,000 people lived here. It became the county seat for the newly established White Pine County. They built a courthouse. Stage coaches connected the town to Austin and Pioche and the railroad at Elko.

But the town’s life was short. The excitement lasted on a few years and by the time of the 1870 census, less than 4,000 people remained. The town struggled on. In 1873, a shopkeeper by the name of Cohen, seeing his investment falter, set his store on fire in the hopes of collecting on his insurance. The fire spread and much of the town burned. Another fire destroyed the courthouse in 1885. In 1887, the town’s future died as the county seat moved to Ely. Today, only a few ruins and a cemetery remain. There’s plenty of mining junk left out, along with the leftovers of a cyanide leaching operation and a few junked house trailers used in the last attempt to mine in the area. We see no one as we poke around.

Treasure City

After Hamilton, we head south to Treasure City, located just a mile and a half from Hamilton, but on top of the mountain. We take the wrong road and I find myself out in front of the truck with a shovel, clearing rocks as we make our way up a switchback road to the top. Had we known, another road to the west would have taken us to the top without any trouble. It’s getting time for dinner and we find a place along Main Street where we stop for the evening.

I build a charcoal fire behind the truck. As soon as we have coals, I put in two foil wrapped potatoes and, in a wire basket, begin to grill the steaks we had socked away in the cooler. As the sun drops toward the horizon, the wind picks up and soon we’re both pulling on jackets. We eat dinner, washing it down with a beer. I throw a few pieces of pinion onto the coals and the fire blazes. After chatting for a bit, I take off on my walk.

Shermantown, Eberhardt, and Charcoal Kilns

The next morning, we head south off the mountain and stop by the sites for Shermantown and Eberhardt. We link up to the Hamilton-Pioche stagecoach trail and follow it to US 6. Turning left, he head back into Ely in time for lunch and to gas up the truck. Then we head south, stopping at the Ward Charcoal Kilns, a state historic site. It’s interesting that there was a large charcoal operation in this desert region. They harvested all the pinion and juniper for miles around to feed these massive kilns. The charcoal was mostly used to roast the ore in the milling process. Leaving the kilns behind, we head down US 93, stopping at Pioche, another mining town.

Pioche and Home

Pioche is still alive and holding on now as an out-of-the-way tourist town. The community received a new lease on life in World War Two, at a time when the government was forcing the closure of gold mines as non-essential industries. But the ground around Pioche included large deposits of zinc,. Considered an essential mineral for the war effort, zinc mining lead to a revival of Pioche. They continued mining zinc around Pioche till the 1980s. We stop long enough to have dinner at the Overland Saloon, and then headed on home. At Panaca, a Mormon farming community, we leave US 93 and head east, toward Cedar City. An hour later, as we approach the city with the sun setting to our back, the red hills glow in the evening light.

A photos were slides which I digitally copied.

Camp Bangladesh: another adventure with Ralph

Sources:

Shawn Hall: Romancing Nevada’s Past: Ghost Towns and Historical Sites of Eureka, Lander and White Pine Counties(University of Nevada Press, 1994)

W. Turrentine Jackson, Treasure Hill, (University of Arizona Press, 1962)

Russell R. Elliott, History of Nevada, revised edition. (University of Nebraska Press, 1987).

_________., Nevada’s Twentieth-Century Mining Boom: Tonopah, Goldfield, Ely (University of Nevada Press, 1966).

Pat and I have traveled that area many times when we were traveling the west many years ago. His love of geology, history of the mines and the back roads were a favorite of ours. Thanks for sharing Jeff

I recall a couple of conversations with Pat about mining camps.

Such an interesting post, Jeff! Thanks for sharing the stories of the mining camps. I have many hoary memories of time I’ve spent in Cedar City. Happy Valentine’s Day! ❤️

As a geologist, I except you are somewhat knowledgeable about mining camps.

As always, I enjoy reading of your past trips, especially in a part of the country I have not been able to spend much time in.

I find myself missing that part of the country… and need to get back out there (maybe early in the fall).

We have family in Vegas, so have visited Nevada many times. Most of the sites we’ve visited have been in the southern part of the state, besides driving through to get to Arizona or Utah.

While Vegas and Reno are their own world, rural Nevada is wonderful, in my opinion.

https://fromarockyhillside.com/2025/02/11/a-great-basin-mining-adventure/

I never would have thought of possibly falling into a mine shaft. Perhaps those were the original land mines.

Land mines, lol. Actually, there have been a move over the past several decades to close off mine shafts and drifts as they are deadly.

What a great adventure and trip. Thanks for sharing.

Ralph and I took a dozen or so of these trips. I should write up more of them.

What Kelly said……and so many interesting experiences. I was in Nevada, Utah and Wyoming earlier this year. So many beautiful sites/sights!

I remember your trip, Judy. It’s beautiful country, but few get into the really remote areas of Nevada.

You’ve taken so many interesting trips!

I have been blessed!