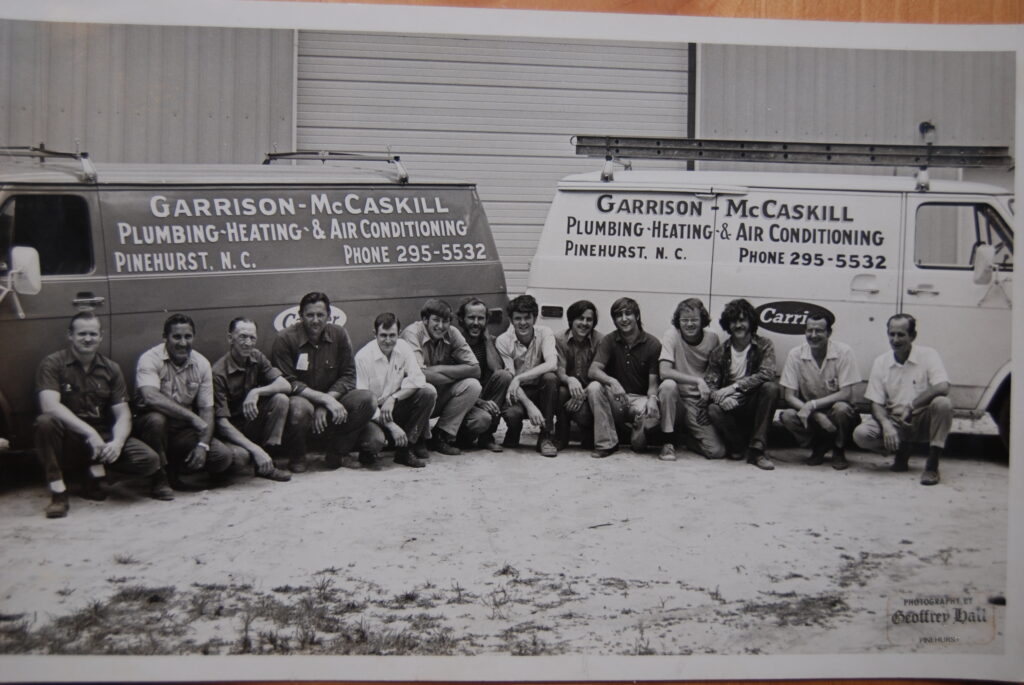

Jeff Garrison

Bluemont and Mayberry Churches

March 27, 2022

Luke 9:51-61

At the beginning of worship

As we continue our Lenten theme of “Why Church?” consider the role of church to reorient our lives.

Back in the 1980s, Neal Postman wrote a classic book titled, Amusing Ourselves to Death. Even before the rise of 24/7 news programs and the internet for everyone, Postman understood that we are drowning in information.[1] And it’s gotten worse. All this noise that surrounds us, challenges and confuses. It competes for our attention. Sadly, church only provides an hour or two a week counterpoint. Here, we point people to Jesus Christ. He’s the the one person to whom we should give our attention, not the soundbites that surround our lives.

Before the reading of the Scripture:

“We do well to remember that the Bible has far more to say about how to live during the journey than about the ultimate destination.”[2] Our passage today comes at a turning point in Luke’s gospel.

Jesus begins to wrap up his ministry in Galilee and for the journey toward Jerusalem. Luke uses this travel narrative as a unifying theme for the middle section of his gospel. [3] Jesus doesn’t arrive in Jerusalem for another ten chapters. During this meandering journey, there are lots of opportunity for Jesus to teach the disciples. Today, we’ll look at one such lesson of how we’re to live during our journeys.

High points and rejections in the gospel:

Earlier in this chapter, Jesus with the handful of the disciples experienced the “Transfiguration.”[4] It’s a high point of the gospel, ranking up there with Jesus’ baptism.[5] Interestingly, Luke follows both these “high points” with a story of rejection.[6]Jesus’ ministry began with his baptism followed by forty days of temptation. Then, he experienced rejection by his hometown.[7]

Now, following the transfiguration, where three disciples see Jesus in his full glory, the rejection comes from a Samaritan village. Jesus uses this rejection to teach the hardship of discipleship. Are we willing to risk rejection to be a disciple? Think seriously about that question as I read this passage.

After the reading of Scripture:

Rejection along the AT

When hiking the Appalachian Trail, I headed into Gorham, New Hampshire for the evening. It’s a small town near the Maine border. I needed to resupply for the next section of trail. I was down to only oatmeal in my food bag and didn’t have enough fuel for my stove to even prepare that.

On my hike I carried with me a multi-fuel stove that could burn regular gasoline. The benefit of such a stove is that I didn’t have to buy gallon containers of white gas at a hardware store, of which I’d only need a liter. It saved me on gas. I’d only spend a quarter or maybe 30 cents to fill up my bottle. Gasoline was a lot cheaper than Coleman fuel, and both fuels were cheaper back then.

So, I stopped at a local Exxon station on the edge of town, leaned my pack against the pump, and pulled out my fuel bottle. As I reached for the nozzle, the cashier ran out of the store yelling obscenities and telling me I couldn’t fill up my bottle.

“Why,” I asked?

“You might spill gas.”

“I’ll be careful. I haven’t yet spilled any and have filled this bottle at least a dozen times.”

“We don’t allow it,” she said.

I was mad.

“It’s a good thing I’m not driving,” I told her, “I’d run out of gas before I filled up at your station.”

Looking back, even without gasoline, I was able to throw some gas onto what was becoming a metaphorical fire. She cursed me and said she wished all us hikers would go back to where we came. In response, I pulled out my journal, wrote down the name of the station, and asked her for its address. I promised to send letters to the Chamber of Commerce and to Exxon Corporate Headquarters. She had a few more choice words for me as I walked down the street and filled up my fuel bottle at the next station.

Having been rejected, I found myself steaming. The next morning, as I left town and hiked north, I crafted letters in my head. Then I realized the negative energy I put into the situation. I let it go. I never sent those letters.

What would Jesus do?

Had Jesus been among us hikers, I think he’d told me to do just that. Drop it. Harboring such feelings is never good. It eats at your soul. We cannot control how other people react to us; we can only control how we react toward them.

Jesus heads toward Jerusalem

Jesus now heads toward Jerusalem, taking the disciples with him. The text says he “sets his face” toward Jerusalem, a phrase echoed throughout the next ten chapters. On this journey, we learn things not mentioned in the other three gospels. Jesus is not just walking; he’s teaching and healing.[8]

If Jesus had a GPS and set the destination for Jerusalem, the machine would have been constantly squawking “recalculating, recalculating” as he wanders around. It’s in this wandering we find some of our most beloved parables, such as the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son. Along the way, Jesus stops and teaches people about who God is and how they should relate to their neighbors.

Those not wanting to see Jesus

But not everyone wants to see Jesus. Luke informs us that the Samaritans don’t want anything to do with Jesus because he has sent his face toward Jerusalem. The Samaritans, who don’t see Jerusalem as holy and who worship on another mountain, have grown weary of self-righteous Jews trampling through their land on their way to Jerusalem.[9] They’re just like the gas station attendant, who was tired of hikers coming through her town. In Biblical times, many Jews from Galilee would take the longer away around Samaria to avoid such encounters.

Hotheaded response of the disciples

Kind of like me going into that New Hampshire village to resupply, the disciples try to arrange food and lodging for their journey. They become upset with the reaction they receive. “Let’s nuke ‘em!” “Let’s blow them to smithereens!” “Let’s get her in trouble with her boss, or the corporation.” Ever hear people talk about enemies like that?

Two of the disciples, James and John, whom Jesus nicknamed “Sons of Thunder,”[10] ask Jesus if he wants them to do away with this village… “You know, Jesus, just a little fire from heaven. It’ll melt their hearts.”

Today, many of us have probably thought similar things about Putin and Russia. And we should think about this in regard those whom we perceive as political enemies. Like the disciples, we have thin skin. Jesus doesn’t take rejection personally and encourages the disciples to get over it. After all, scripture clearly states that vengeance isn’t ours![11]

The difficulty of discipleship

Yet, there are also those wanting to join Jesus on this journey. We’re not told if Jesus turns them away, but he certainly used no ad agency to sell his trip. “I have no place to lay my head,” he says. The Message translation here has Jesus saying, “we’re not staying at the best inns, you know.”

Following Jesus isn’t easy. Jesus makes a demand on our lives. “Are you ready to follow me,” Jesus asks? “If you want to follow me, I have to be first and foremost in your lives,” he says. “Nothing can come before me!”

Do we put things before Christ? Think about your life and what you value. Are you willing to give it all up for Jesus? Is Jesus at the center of your life? Is he what’s most important?

The two parts of this passage

Tension exists between the first and second parts of this passage. In the first part, we’re told not to be so zealous that we forget the mission. Jesus came to save, not to destroy. The desire for revenge or violence toward our enemies goes counter to Jesus’ teaching.[12] In the second half of the passage, Jesus reminds us that following him is tough. Yet, if we decide to follow, Jesus demands our total allegiance. We can’t jump halfway in, it’s all or nothing.

Today’s meaning

What does this passage say to us today? One thing we can gleam: If we want to be a follower of Jesus, we must be willing to stand up against the contempt that is so prevalent in our society today.[13] Jesus didn’t allow the disciples to have contempt toward the Samaritans, and I don’t think he’s happy about how we treat others.

The problem of contempt

Contempt for others is a human problem. Certainly, in recent years, it’s grown like a wildfire in our national politics. Adhominem attacks are tossed around like grenades. We become more interested in sound bites than logic and fail to realize such grenades contain a basic fallacy.

Ad hominem means “against the man.” Such a fallacy occurs when, instead of attacking an issue, one belittles or dehumanizes the person on the other side of an argument. I don’t think Jesus appreciates this, which is one of the reasons I think he tells us to pray for our enemies.[14] When you pray seriously for others, they don’t remain enemies and we certainly can’t hold them in contempt.

Wishing others would go away

Just think about this. When we hear something we agree with, we jump on the bandwagon without thinking. It then becomes easy for us to let our contempt rule. “Let’s call down some fire from heaven.” Sounds good, doesn’t it? It has gotten so easy to wish those we don’t like would disappear or go away.

We not only see this tendency in our national politics, but locally… And it happens within churches, between friends, and even within members of a family. When we know we’re right and assume others are not only wrong but also evil or stupid, we quickly slide into thinking we’d be better off without them. We show contempt. We’re like James and John in our story today.

Sadly, it’s easy to mouth off. And our words risk creating a larger divide between us and the other. But the Christian faith isn’t about creating divisions. It’s about bringing people together. It’s about standing up for others, even those we may not agree with. It’s about not spouting off at the mouth. It’s about thinking before we speak. When we come to church, we need to be reminded that our actions matter.

Conclusion

Today, I think back to that encounter so many years ago in Gorham, New Hampshire. I wonder what would have happened if I had gone back to that cashier at the Exxon station and apologized. I wouldn’t have to say she was right, but I could have acknowledged my response and my thoughts about her were misguided. As humans, we can’t be responsible for what someone else does. We can only be responsible for what we do and how we react.

Consider what this all might do with our need for church. When we come here, we’re reminded that our thoughts, desires, and feelings are not what’s most important. Instead, what matters is following our Savior. If we only look out for ourselves, we will lose the path Jesus sets before us. Amen.

©2022

[1] The future danger was not slavery in the form of totalitarianism (as in George Orwell’s 1984, but a slavery to our amusement (as in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World). See Neal Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death. (NY: Viking, 1985).

[2]This quote came from a Facebook Meme posted by the Clergy Coaching Network and attributed to Philip Yancey.

[3] See Fred B. Craddock, Luke: Interpretation: A Biblical Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1990), 139-142.

[4] Luke 9:28ff.

[5] Luke 3:21-22.

[6] Craddock, 142.

[7] Luke 4:16ff.

[8] For a discussion on Jesus heading to Jerusalem but not making progress, see James R. Edwards, The Gospel of Luke (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015), 294, n. 4.

[9] Norval Geldenhuys, The New International Commentary on the New Testament: Gospel of Luke (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1982), 292-3. For the difference in worship between Jews and Samaritans, see John 4:19-20.

[10] Mark 3:17

[11] Deuteronomy 32:35, Romans 12:19, and Hebrews 10:30.

[12] Geldenhuys, 292.

[13] For a detailed discussion on the problem of contempt, see Arthur C. Brooks, Love Your Enemies (New York: HarperCollins, 2019).

[14] Matthew 5:44