Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018), 272 pages including notes and an index.

Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018), 272 pages including notes and an index.

One would need to be deaf and blind not to realize there are serious problems in American society. Instead of rationally discussing issues that divide us, we join polarized camps and dismiss those with whom we disagree. We use unflattering names or spread false rumors about those we see as opponents. Instead of debating topics of concern, we yell at those with different views. It’s as if we believe that the one who yells loudest is right, which is absurd. Instead of looking for common ground upon which we might build a relationship, we use perceived differences to Balkanize ourselves into camps of like-minded people. And when we are only around those who look, think, and act like us, we just confirm our preconceived biases. And there is no doubt that 24-hour cable news and the algorithms of social media have only strengthened this divide. We no longer watch the same news programs and entertainment, nor read the same authors and newspapers. Instead, with a world flooded with information, everything comes tailored for us as individuals. This whole system, according to Sasse, makes us very lonely.

I was a little shocked when I began reading this book on how divided America is to read Sasse’s critique of America culture and how our problems stems from loneliness. I did wonder if he makes more out of the problem of loneliness than it deserves. He also suggests that the decline of the traditional home as another reason for society’s problems. I hope his ideas are debated. Perhaps they can play a role in building a more civil society. That said, there are critiques he makes that will make everyone a little uncomfortable. He challenges an article that identifies the genesis of nasty politics from the 1994 election and Newt Gingrich. Sasse suggests that Gingrich was only a backlash of nasty politics of the Democrats against the Robert Bork nomination to the Supreme Court in 1986. (Personally, I’m old enough to think the issue goes back further than 1994 or 1986). But those on the right can’t rejoice, for in the next chapter, he challenges Fox News and suggests they profit greatly from monetizing the fear. He particularly attacks Sean Hannity for not only preying on this fear and inciting rage, but also ignoring any evidence he finds inconvenient. By the time most readers with die-hard political positions, whether on the right or left, have finished the first half of the book, they’ll have found cherished positions challenged. Sadly, many will probably skip the second half of the book where Sasse suggests strategies for building bridges instead of walls.

Sasse grew up in a small town in Nebraska. It was a place with strong rivalries between towns and sports played a major part of these rivalries. He idolatrizes his father, who was a coach. He obviously grew up in a traditional family. Sasse, himself, attended college on a wrestling scholarship. He would later earn a Ph.D. at Yale in American history and became the president of a small Midwestern liberal arts college. He also comes from a strong Lutheran Church background. His experiences with small towns, family, sports, religion, and education come together in this book as he seeks a way to bridge in the impasse that exists within American society.

Sasse’s eureka moment of his childhood came when he attended a Nebraska football game. There he was in the big house in the prairie, with 100,000 other folks, all in red, cheering on the cornhuskers. A few rows a way he spotted a group of people from a neighboring town that was a big rival of his town. These were folks his town cheered to their demise at Friday night football games, yet here they were, enemies, cheering on Nebraska. The problem caused by isolation (and loneliness) when we maintain isolation is that we fail to realize that we often have a lot in common with those we see as “them.” He learned from an early age that these folks from a rival school district weren’t really enemies. However, Sasse doesn’t suggest we end rivalries, for competition helps us be our best.

In the second half of this book, Sasse lays out several ideas on how we can begin to break down the walls separating us from them. In his first chapter in this half, titled “Become Americans Again,” Sasse provides a civics lesson about what should unite us. I found it refreshing to read a Lutheran who can write like a Calvinist as he calls for us to admit our that we’re all flawed. He encourages us to set limits on our (and our children’s) use of technology, to be more open to diverse debate within the university (an idea, he points out, that he and Obama agree on), and to develop roots while also exploring outside our own tribe. While most readers won’t agree 100% with the author (and I assume that would be fine with Sasse), Americans would be better off we seriously debated his thesis as we seek to breakdown the divides that separate us. This is a good book for all Americans to read (and maybe even those in Russia or China to read to learn more about what America should look like).

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Beautiful pottery breaks. Today, during the sermon, hold on to the shard you’ve been given, and ponder God’s judgment. Think about what it means to be broken, unfixable. But don’t throw away the shard. When the service is over, take it over to Liston hall, where we’ll attempt to put it back together and see what kind of design Sue Jones created for us.

Beautiful pottery breaks. Today, during the sermon, hold on to the shard you’ve been given, and ponder God’s judgment. Think about what it means to be broken, unfixable. But don’t throw away the shard. When the service is over, take it over to Liston hall, where we’ll attempt to put it back together and see what kind of design Sue Jones created for us.

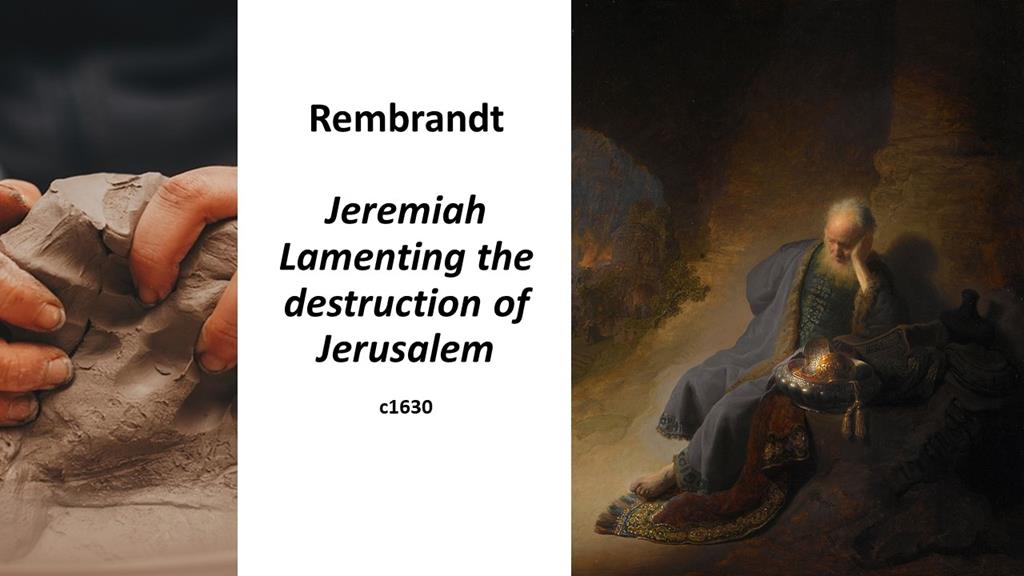

For the people of Jeremiah’s day, storm clouds are gathering. It’s not looking good. It’s kind of like that vision we get from the song “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” those wayward cowpokes who are eternally damned to chase the Devil’s herd. Storm clouds are always frightening. But let’s think about ourselves.

For the people of Jeremiah’s day, storm clouds are gathering. It’s not looking good. It’s kind of like that vision we get from the song “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” those wayward cowpokes who are eternally damned to chase the Devil’s herd. Storm clouds are always frightening. But let’s think about ourselves. You know, we have blessed as a nation in that no foreign army has invaded us for over 200 years. The last was during the War of 1812. It’s been a century and a half since those of us who are from the South experienced the horrors of having towns and cities burned, armies destroyed, and people suffering. We can only image what it was like for the people in Savannah during that Civil War, hearing the distant bombardments of Fort Pulaski and Fort MaAllister, and then, in 1864, the rumors building fear as Sherman’s army approaches.

You know, we have blessed as a nation in that no foreign army has invaded us for over 200 years. The last was during the War of 1812. It’s been a century and a half since those of us who are from the South experienced the horrors of having towns and cities burned, armies destroyed, and people suffering. We can only image what it was like for the people in Savannah during that Civil War, hearing the distant bombardments of Fort Pulaski and Fort MaAllister, and then, in 1864, the rumors building fear as Sherman’s army approaches. In this section of Jeremiah, the approaching Babylonian army is described as a hot wind blowing up a frightful dust cloud off the desert. This could be like the dust clouds off Africa that eventually turn into hurricanes that threaten our coastline. In the part I skipped, we hear how the rumors begin to filter down to Judah and Jerusalem, starting way to the north, above the Sea of Galilee, in the territories of Dan. We know a similar drill with hurricanes as they approach the Leeward Island and the Lesser Antilles and the Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Cuba, and the Bahamas as the storm makes its way across the South Atlantic. Sometimes these storms are like Jeremiah’s vision, bringing total destruction. Just as we hurt seeing the damage Dorian caused the Bahamas, we also worry what might happen to us if the storm doesn’t turn, Jeremiah is bothered by his vision. He can see it happening and cries out in anguish. But despite the heartache of what he sees, he faithfully proclaims God’s word.

In this section of Jeremiah, the approaching Babylonian army is described as a hot wind blowing up a frightful dust cloud off the desert. This could be like the dust clouds off Africa that eventually turn into hurricanes that threaten our coastline. In the part I skipped, we hear how the rumors begin to filter down to Judah and Jerusalem, starting way to the north, above the Sea of Galilee, in the territories of Dan. We know a similar drill with hurricanes as they approach the Leeward Island and the Lesser Antilles and the Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Cuba, and the Bahamas as the storm makes its way across the South Atlantic. Sometimes these storms are like Jeremiah’s vision, bringing total destruction. Just as we hurt seeing the damage Dorian caused the Bahamas, we also worry what might happen to us if the storm doesn’t turn, Jeremiah is bothered by his vision. He can see it happening and cries out in anguish. But despite the heartache of what he sees, he faithfully proclaims God’s word. The second part of my reading describes the aftermath. Destruction is total. Starting with verse 23, the poem recalls the “dismantling of creation.”

The second part of my reading describes the aftermath. Destruction is total. Starting with verse 23, the poem recalls the “dismantling of creation.” For Christians living in America, we may have a hard time relating to Jeremiah’s vision. But many Christians, those living around the globe in places where it’s dangerous to worship Jesus, recognize Jeremiah’s anguish as their own. For them, gathered around this table on World Communion Sunday, they are in danger. They know what it means to worship in fear, to experience the loss of jobs, of their homes and their land because of their faith. They know what it means to be locked up, to be tortured, and to watch loved ones be taken away and never return because of their faith. Christians are suffering in China, in Eritrea, in North Korea, in Iran and Iraq, in Syria and parts of India. We must stand by those who do not enjoy the freedom to worship as we enjoy it.

For Christians living in America, we may have a hard time relating to Jeremiah’s vision. But many Christians, those living around the globe in places where it’s dangerous to worship Jesus, recognize Jeremiah’s anguish as their own. For them, gathered around this table on World Communion Sunday, they are in danger. They know what it means to worship in fear, to experience the loss of jobs, of their homes and their land because of their faith. They know what it means to be locked up, to be tortured, and to watch loved ones be taken away and never return because of their faith. Christians are suffering in China, in Eritrea, in North Korea, in Iran and Iraq, in Syria and parts of India. We must stand by those who do not enjoy the freedom to worship as we enjoy it. Remember, we have an insight Jeremiah didn’t have. We know about the resurrection, how the grave is not the end. Jeremiah knew that somehow God’s destruction wasn’t going to quite be total. We know that even if it appears total, as it does at death, as when we peer down into the grave, God is still God and the end is not the end.

Remember, we have an insight Jeremiah didn’t have. We know about the resurrection, how the grave is not the end. Jeremiah knew that somehow God’s destruction wasn’t going to quite be total. We know that even if it appears total, as it does at death, as when we peer down into the grave, God is still God and the end is not the end. The center of the gospel is the hope we have in the resurrection to eternal life. And for that reason, we can face those storm clouds. We can face the stampede of Satan’s herd and the cowboys running roughshod across the skies, and know that as bad as things are, there’s hope. We may feel like we’re just broken shards of pottery, but God has the power to make what’s broken new and whole. Believe in God. Hold on to such hope. Amen.

The center of the gospel is the hope we have in the resurrection to eternal life. And for that reason, we can face those storm clouds. We can face the stampede of Satan’s herd and the cowboys running roughshod across the skies, and know that as bad as things are, there’s hope. We may feel like we’re just broken shards of pottery, but God has the power to make what’s broken new and whole. Believe in God. Hold on to such hope. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison You might be wondering about all this emphasis on pottery as we look at the Prophet Jeremiah. Pottery was a revolutionary technology in the ancient world. It allowed more movement as people could store things in pots, such as water and grain.

You might be wondering about all this emphasis on pottery as we look at the Prophet Jeremiah. Pottery was a revolutionary technology in the ancient world. It allowed more movement as people could store things in pots, such as water and grain.

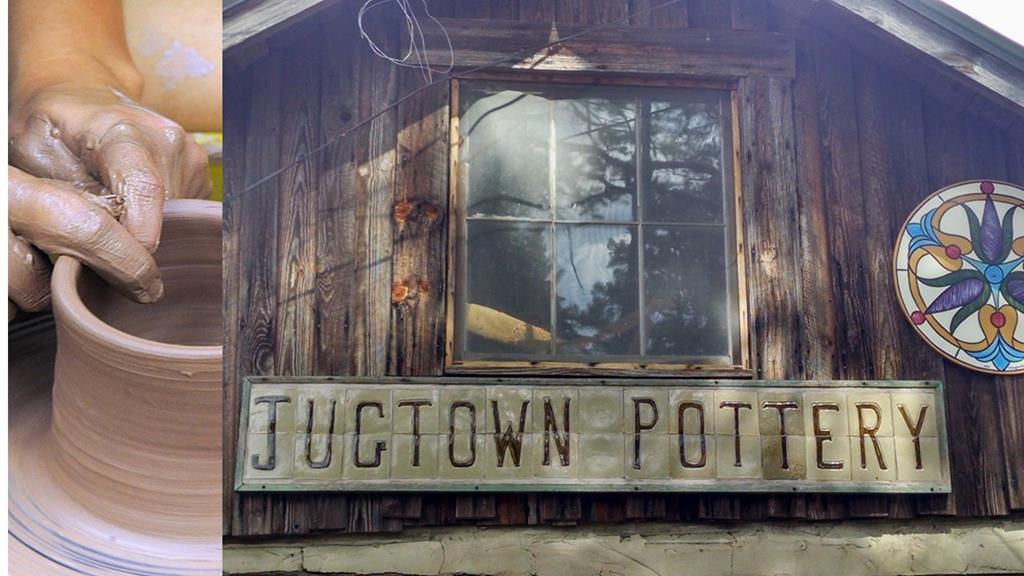

About twenty-five miles northwest of where I was born, where the Carolina Sandhills turn into clay hills, is a dot on the map known as Jugtown. It’s a place I like to visit when I am back in that part of the world. Today, the area around Jugtown and Seagrove is dotted with crafty potters who turn muck into beautiful and useful art. It’s a treat, as we’ve just seen on the video, to watch a potter turn a lump of clay on the wheel into something useful and beautiful.

About twenty-five miles northwest of where I was born, where the Carolina Sandhills turn into clay hills, is a dot on the map known as Jugtown. It’s a place I like to visit when I am back in that part of the world. Today, the area around Jugtown and Seagrove is dotted with crafty potters who turn muck into beautiful and useful art. It’s a treat, as we’ve just seen on the video, to watch a potter turn a lump of clay on the wheel into something useful and beautiful. Jugtown received its name, as you can guess, from jugs. The law-abiding folks in the clay hills around there, I’m sure, intended their jugs to store molasses, honey, cane syrup, or something similar. Of course, it was also used to hold liquefied corn (also known as white lightning or moonshine). But with the advent of mason jars, such use of the jugs ceased. But early on, some of the potters had new ideas. In 1917, two of the potters began selling their wares in a store and tea shop in New York City. They emphasized utilitarian pots, things that could be used such as pie plates, crocks, mugs, and bowls. They stamped their unique mark on the bottom of each vessel. Over time, they began to teach new potters the craft and as one generation passed, another took up the wheel. Today, if you go to the area around Jugtown, you’ll find dozens or potters selling their wares. These artists have brought new life into that worthless clay that sticks to your shoes and gums up a plow.

Jugtown received its name, as you can guess, from jugs. The law-abiding folks in the clay hills around there, I’m sure, intended their jugs to store molasses, honey, cane syrup, or something similar. Of course, it was also used to hold liquefied corn (also known as white lightning or moonshine). But with the advent of mason jars, such use of the jugs ceased. But early on, some of the potters had new ideas. In 1917, two of the potters began selling their wares in a store and tea shop in New York City. They emphasized utilitarian pots, things that could be used such as pie plates, crocks, mugs, and bowls. They stamped their unique mark on the bottom of each vessel. Over time, they began to teach new potters the craft and as one generation passed, another took up the wheel. Today, if you go to the area around Jugtown, you’ll find dozens or potters selling their wares. These artists have brought new life into that worthless clay that sticks to your shoes and gums up a plow. Jeremiah is called to the potter’s house where God uses a common image of the ancient world to make a profound message. God’s word comes to him as he watches the potter over and over start off one direction with clay, and it not working, so he reworks the clay into something more suitable. This sounds hopeful. God will continue to work with us until we become a vessel that serves some purpose. One preacher, writing about this text, said that it demonstrates a sovereign God, “not a God of absolute capricious control, but a gracious willingness to change his plan to benefit his flawed people. When God discovers this fatal flaw in his people, he does not simply destroy them; he offers to start over.”

Jeremiah is called to the potter’s house where God uses a common image of the ancient world to make a profound message. God’s word comes to him as he watches the potter over and over start off one direction with clay, and it not working, so he reworks the clay into something more suitable. This sounds hopeful. God will continue to work with us until we become a vessel that serves some purpose. One preacher, writing about this text, said that it demonstrates a sovereign God, “not a God of absolute capricious control, but a gracious willingness to change his plan to benefit his flawed people. When God discovers this fatal flaw in his people, he does not simply destroy them; he offers to start over.”  Jeremiah’s task is to preach impending judgment to God’s people. If they don’t shape up, if they don’t stop running around chasing foreign gods and idols, if they act like they’re in control and the God of the Universe is of no matter, they will be punished. Just as the potter can shape a vessel in a new way, they can be handled in a different manner. God can shape another nation to punish. There appears to still time, at this point, for the Hebrew people to change. Later prophecies of Jeremiah hold out no hope of repentance, but here, it’s not too late.

Jeremiah’s task is to preach impending judgment to God’s people. If they don’t shape up, if they don’t stop running around chasing foreign gods and idols, if they act like they’re in control and the God of the Universe is of no matter, they will be punished. Just as the potter can shape a vessel in a new way, they can be handled in a different manner. God can shape another nation to punish. There appears to still time, at this point, for the Hebrew people to change. Later prophecies of Jeremiah hold out no hope of repentance, but here, it’s not too late. The message of this passage is that God has the power to reshape us, but we must let God work with us. If we resist God’s shaping, we may not be completely crushed, but we won’t fulfill the potential for which we were designed. The intention of our passage isn’t to be fatalistic and say we have no control. Instead, it’s a warning that we’re to work with God and not against him.

The message of this passage is that God has the power to reshape us, but we must let God work with us. If we resist God’s shaping, we may not be completely crushed, but we won’t fulfill the potential for which we were designed. The intention of our passage isn’t to be fatalistic and say we have no control. Instead, it’s a warning that we’re to work with God and not against him. When you leave this sanctuary today, ponder these questions: Where is God at work in the world? How can we participate? How can we be the clay that trusts the potter? Amen.

When you leave this sanctuary today, ponder these questions: Where is God at work in the world? How can we participate? How can we be the clay that trusts the potter? Amen.

The campsites are rather expensive for pit toilets and no showers ($25/night), but we loved our site. It was just steps from the river and we had the place to ourselves. We slept to the sound of water running over rocks (augmented by the sounds of birds, frogs, insects, and the wind). It was a wonderful place to camp. And every evening, I took a swim in the river.

The campsites are rather expensive for pit toilets and no showers ($25/night), but we loved our site. It was just steps from the river and we had the place to ourselves. We slept to the sound of water running over rocks (augmented by the sounds of birds, frogs, insects, and the wind). It was a wonderful place to camp. And every evening, I took a swim in the river. After getting back and having a hurricane threaten, another full moon came around. This time, at home and on a semi-clear evening, I made the best of it by paddling around Pigeon Island (about 6 miles). It was a magical evening starting with incredibly red skies and then the beauty of the moon.

After getting back and having a hurricane threaten, another full moon came around. This time, at home and on a semi-clear evening, I made the best of it by paddling around Pigeon Island (about 6 miles). It was a magical evening starting with incredibly red skies and then the beauty of the moon.

Last week we learned of Jeremiah’s call by God as a prophet to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant.”

Last week we learned of Jeremiah’s call by God as a prophet to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant.”

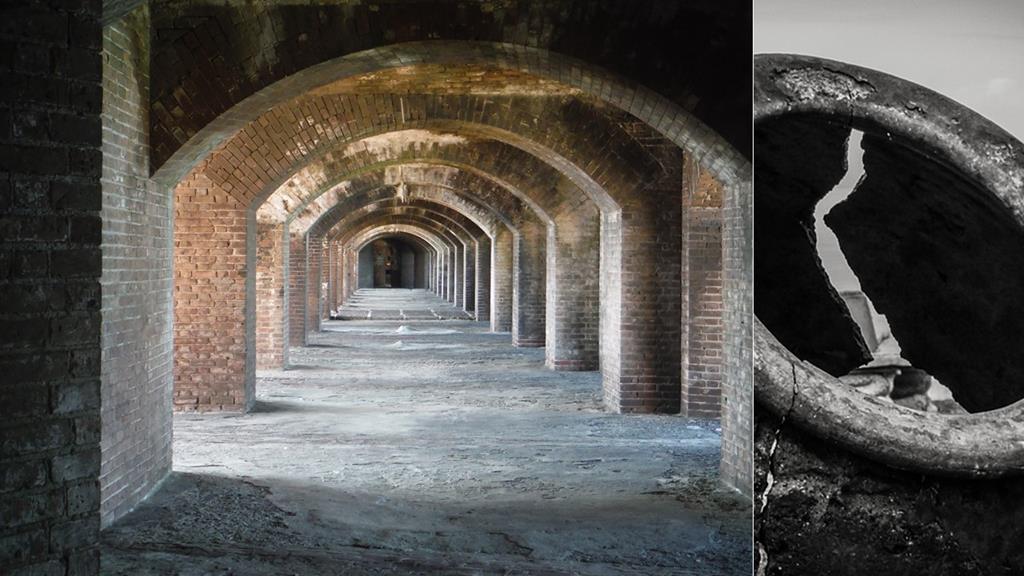

In the spring of 2018, my sister, my father, and I took a trip to the Dry Tortugas. I’m sure many of you read the article I had about the trip in The Skinnie.

In the spring of 2018, my sister, my father, and I took a trip to the Dry Tortugas. I’m sure many of you read the article I had about the trip in The Skinnie. If you’re going to have a fort with a substantial garrison on an island without fresh water, you must find a way to overcome that limitation. The engineers who designed Fort Jefferson came up with a unique way to address the lack of water. They built a series of cisterns under the walls of the fort and designed a system to funnel rainwater into the cisterns where they provided water for later use. The fort could hold nearly two million gallons of water. It was thought there would be enough water and provisions within the walls for the fort to survive a yearlong siege.

If you’re going to have a fort with a substantial garrison on an island without fresh water, you must find a way to overcome that limitation. The engineers who designed Fort Jefferson came up with a unique way to address the lack of water. They built a series of cisterns under the walls of the fort and designed a system to funnel rainwater into the cisterns where they provided water for later use. The fort could hold nearly two million gallons of water. It was thought there would be enough water and provisions within the walls for the fort to survive a yearlong siege. But the plans of men and women often fail. This massive fort, built with millions of bricks and packed dirt, was so heavy that of the 136 cisterns, all but three cracked and allowed saltwater to infiltrate. They became useless.

But the plans of men and women often fail. This massive fort, built with millions of bricks and packed dirt, was so heavy that of the 136 cisterns, all but three cracked and allowed saltwater to infiltrate. They became useless. The cracked cistern image shows Israel’s condition after chasing after non-existent gods. As humans, we all need water. An image of God’s providence found throughout Scripture is that of living water nourishing us.

The cracked cistern image shows Israel’s condition after chasing after non-existent gods. As humans, we all need water. An image of God’s providence found throughout Scripture is that of living water nourishing us.

Friends, we don’t want to be cracked pots. We want to be vessels holding abundant living water that will quench our thirst, and can be shared to others, to quench theirs. Amen.

Friends, we don’t want to be cracked pots. We want to be vessels holding abundant living water that will quench our thirst, and can be shared to others, to quench theirs. Amen. Jeff Garrison

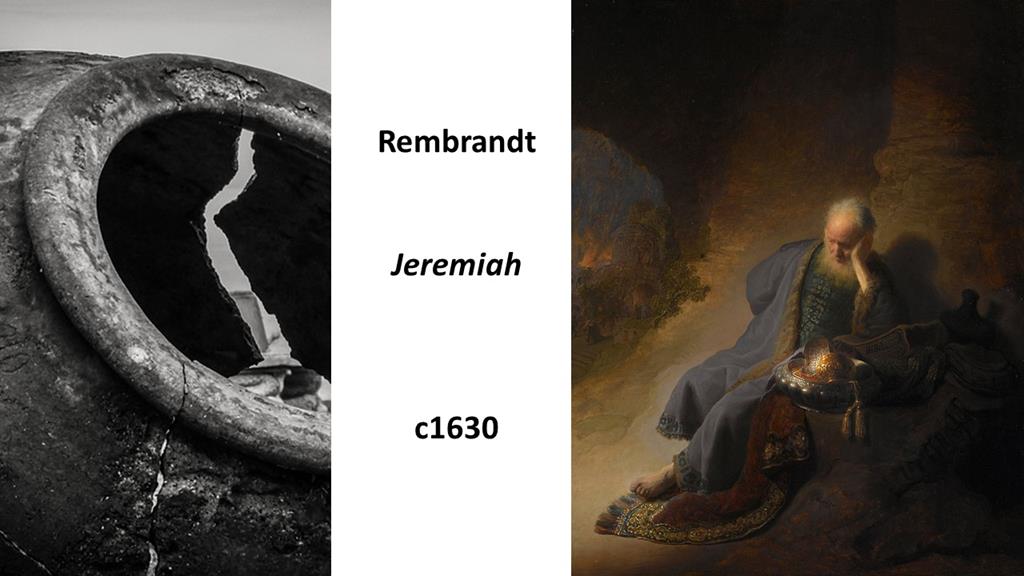

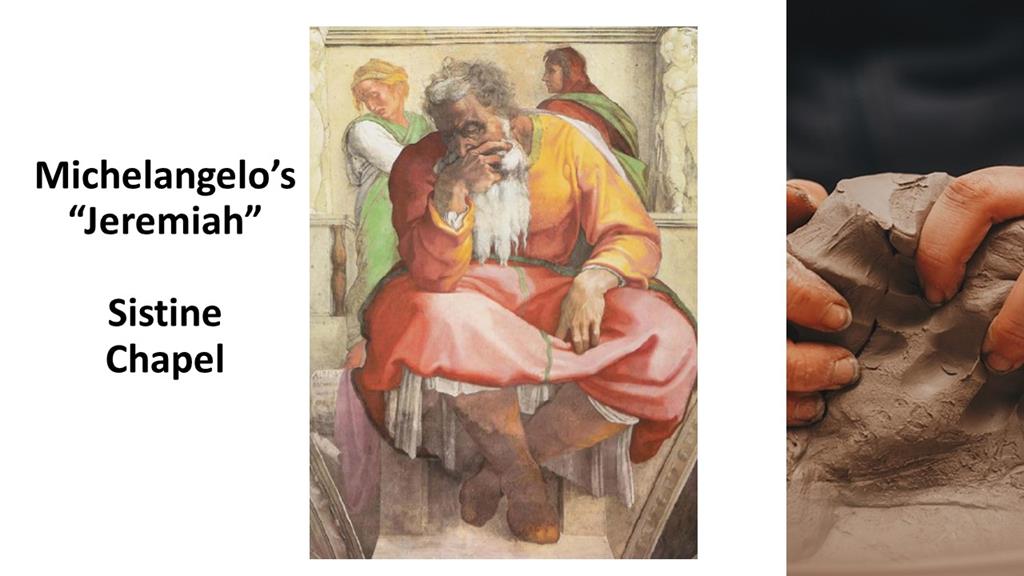

Jeff Garrison The prophet Jeremiah lived in interesting times. He was one of the longest serving prophets in Israel’s history, his calling coming as the Assyrians were losing power. It was a time of optimism in Jerusalem because they had existed as a vassal state under Assyria for over a century. It appeared they might be free once again, as in the years of Kings David and Solomon. Furthermore, Josiah, one of Judah’s few good kings, was implementing religious reforms. But then Josiah is killed in battle against Egypt.

The prophet Jeremiah lived in interesting times. He was one of the longest serving prophets in Israel’s history, his calling coming as the Assyrians were losing power. It was a time of optimism in Jerusalem because they had existed as a vassal state under Assyria for over a century. It appeared they might be free once again, as in the years of Kings David and Solomon. Furthermore, Josiah, one of Judah’s few good kings, was implementing religious reforms. But then Josiah is killed in battle against Egypt. We, too, are living in interesting times. Things are scary in our world: rogue nations having the bomb, individuals going berserk and killing people, terrorists creating political instability, and huge storms leaving behind chaos and destruction. The news often leaves us fearful and angry. And since we often don’t have answers for the problems we face, we blame others. Ben Sasse, a Senator from Nebraska, suggests one of the few things uniting us is our contempt for those of whom we assign blame. “At least,” we say, “we’re not like them.”

We, too, are living in interesting times. Things are scary in our world: rogue nations having the bomb, individuals going berserk and killing people, terrorists creating political instability, and huge storms leaving behind chaos and destruction. The news often leaves us fearful and angry. And since we often don’t have answers for the problems we face, we blame others. Ben Sasse, a Senator from Nebraska, suggests one of the few things uniting us is our contempt for those of whom we assign blame. “At least,” we say, “we’re not like them.”

Jeremiah was a bullfrog,

Jeremiah was a bullfrog, Back in early May, Gary Witbeck and I took a trip into the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. On our second night, we were camping on a platform at a place called “Big Water.” It’s the headwaters for the Suwanee River. As the sun set and evening descended, we watched alligators battle over territory (or maybe they were fighting over mates, or were flirting, we couldn’t tell the difference). While the gators fought, in the background a chorus of frogs sang. Their song would come in waves, starting up the river and working its way down and then back up. The frogs were in perfect harmony. You couldn’t tell one frog’s croak from another. It was quite beautiful.

Back in early May, Gary Witbeck and I took a trip into the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. On our second night, we were camping on a platform at a place called “Big Water.” It’s the headwaters for the Suwanee River. As the sun set and evening descended, we watched alligators battle over territory (or maybe they were fighting over mates, or were flirting, we couldn’t tell the difference). While the gators fought, in the background a chorus of frogs sang. Their song would come in waves, starting up the river and working its way down and then back up. The frogs were in perfect harmony. You couldn’t tell one frog’s croak from another. It was quite beautiful. But this is where the song gets it wrong. The one singing, claims to be a friend of Jeremiah, enjoying drinking his wine. But the Jeremiah of the Old Testament, was often lonely. He didn’t have many friends bellying up to him at the bar. Like a bullfrog, he cried out the message from God that he’s been given, and message that no one wanted to hear, so he was often alone and vulnerable. But he was faithful, and when we consider eternity, that makes all the difference in the world.

But this is where the song gets it wrong. The one singing, claims to be a friend of Jeremiah, enjoying drinking his wine. But the Jeremiah of the Old Testament, was often lonely. He didn’t have many friends bellying up to him at the bar. Like a bullfrog, he cried out the message from God that he’s been given, and message that no one wanted to hear, so he was often alone and vulnerable. But he was faithful, and when we consider eternity, that makes all the difference in the world. You’ll notice in the text that Jeremiah didn’t have a choice in all this. He was chosen by God before the foundation of the earth. Yesterday morning, in the Men’s Bible Study, we were reading Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, where are reminded that God calls us through Jesus Christ to do the work which has been prepared for us.

You’ll notice in the text that Jeremiah didn’t have a choice in all this. He was chosen by God before the foundation of the earth. Yesterday morning, in the Men’s Bible Study, we were reading Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, where are reminded that God calls us through Jesus Christ to do the work which has been prepared for us. Of course, like Jeremiah, we can beg off. Jeremiah said, “I’m just a boy.” Looking around, we might say, “we’re too old.” But God has heard that one, too. Remember Abraham and Sara? How old were they?

Of course, like Jeremiah, we can beg off. Jeremiah said, “I’m just a boy.” Looking around, we might say, “we’re too old.” But God has heard that one, too. Remember Abraham and Sara? How old were they? Jeremiah has been appointed for a mission. Likewise, the church has been appointed for a mission. We’re all called by God to follow Jesus and to point to him as our hope in a world that often seems hopeless.

Jeremiah has been appointed for a mission. Likewise, the church has been appointed for a mission. We’re all called by God to follow Jesus and to point to him as our hope in a world that often seems hopeless. Over the next six weeks, as we work through this series, we’ll be using images of potters. Our image today is a clump of clay, being kneaded like bread dough. The technical term for doing this to clay is “wedged.” The potter takes the clay and stretches and pushes it like a baker works dough. In doing this, all the air pockets are worked out so that the clay is easier to shape on the wheel and afterwards, when firing, the pot won’t have air pockets that’ll explode and destroy the vessel.

Over the next six weeks, as we work through this series, we’ll be using images of potters. Our image today is a clump of clay, being kneaded like bread dough. The technical term for doing this to clay is “wedged.” The potter takes the clay and stretches and pushes it like a baker works dough. In doing this, all the air pockets are worked out so that the clay is easier to shape on the wheel and afterwards, when firing, the pot won’t have air pockets that’ll explode and destroy the vessel. Paul, writing to the Ephesians, encouraged them to put away all bitterness, wrath, anger, wrangling, slander and malice. Such behavior is to be wedged out of us, like air is wedged out of the clay, so that we might be kind to one another, tenderhearted, and forgiving.

Paul, writing to the Ephesians, encouraged them to put away all bitterness, wrath, anger, wrangling, slander and malice. Such behavior is to be wedged out of us, like air is wedged out of the clay, so that we might be kind to one another, tenderhearted, and forgiving. Dorian is gone. It was more a “non-event” here. I ended up not evacuating even though I continued to watch the Weather Channel to see if things might change. But the storm stayed well off the Georgia coast. We received only a little wind and rain. I actually thought we had received very little rain, barely over an inch. Then I looked at the gauge again, 30 minutes later, and it was empty! The bottom of the gauge had sprung a leak. So I have no idea who much water we received. Our neighborhood also maintained power until we were on the backside of the storm. We lost it yesterday morning about 7:30 AM. I had to go out and dig into my camping equipment to fetch a coffee peculator. Since Hurricane Matthew (where I cooked on a camp stove on the front porch), we had replaced the electric stove top with gas. So, yesterday morning, I fixed corned beef hash, poached eggs, and coffee for breakfast, as you can see in the photo.

Dorian is gone. It was more a “non-event” here. I ended up not evacuating even though I continued to watch the Weather Channel to see if things might change. But the storm stayed well off the Georgia coast. We received only a little wind and rain. I actually thought we had received very little rain, barely over an inch. Then I looked at the gauge again, 30 minutes later, and it was empty! The bottom of the gauge had sprung a leak. So I have no idea who much water we received. Our neighborhood also maintained power until we were on the backside of the storm. We lost it yesterday morning about 7:30 AM. I had to go out and dig into my camping equipment to fetch a coffee peculator. Since Hurricane Matthew (where I cooked on a camp stove on the front porch), we had replaced the electric stove top with gas. So, yesterday morning, I fixed corned beef hash, poached eggs, and coffee for breakfast, as you can see in the photo.

This photo was taken at Delegal Creek last night as the sunset. Hurricane Dorian is several hundred miles south at this point. Today, as I write this, we have had a few bands of rain with wind, but nothing too bad. The storm should brush by us late this afternoon or in the evening, but will be staying off shore. Prayers to those in the Bahamas who suffered so greatly, and for those in the Carolinas who may experience more of this storm’s fury.

This photo was taken at Delegal Creek last night as the sunset. Hurricane Dorian is several hundred miles south at this point. Today, as I write this, we have had a few bands of rain with wind, but nothing too bad. The storm should brush by us late this afternoon or in the evening, but will be staying off shore. Prayers to those in the Bahamas who suffered so greatly, and for those in the Carolinas who may experience more of this storm’s fury.

At the end of the sixth grade at Bradley Creek Elementary School, there was a graduation banquet. It was held in the evening, which made it special, and in the cafeteria, which wasn’t so special. I’m sure we had macaroni and cheese. We always had mac and cheese. There must have been a rule that you couldn’t open the cafeteria without mac and cheese. But this was a special meal, so maybe there was a slice of ham or a piece of chicken and a piece of cake that was larger than the one inch cubes they fed us at lunch.

At the end of the sixth grade at Bradley Creek Elementary School, there was a graduation banquet. It was held in the evening, which made it special, and in the cafeteria, which wasn’t so special. I’m sure we had macaroni and cheese. We always had mac and cheese. There must have been a rule that you couldn’t open the cafeteria without mac and cheese. But this was a special meal, so maybe there was a slice of ham or a piece of chicken and a piece of cake that was larger than the one inch cubes they fed us at lunch. In the bulletin, I titled this sermon “Humility and Hospitality.” The problem with coming up with a title a few weeks before writing a sermon is that you often have no idea where the sermon is heading. I later decided that a better title might be Banquet Etiquette. But as I continued to study and ponder, I decided to put a question mark at the end. Yes, Jesus expects us to be humble and not pretentious. Such advice will also keep us from being in an embarrassing position. Yes, on the surface, this is about etiquette. But is this what Jesus is driving? Is this Jesus’ attempt to be the Emily Post of the first century? Or is there a deeper message here?

In the bulletin, I titled this sermon “Humility and Hospitality.” The problem with coming up with a title a few weeks before writing a sermon is that you often have no idea where the sermon is heading. I later decided that a better title might be Banquet Etiquette. But as I continued to study and ponder, I decided to put a question mark at the end. Yes, Jesus expects us to be humble and not pretentious. Such advice will also keep us from being in an embarrassing position. Yes, on the surface, this is about etiquette. But is this what Jesus is driving? Is this Jesus’ attempt to be the Emily Post of the first century? Or is there a deeper message here? Remember what I said about the Sabbath, before reading this passage? That it was a foretaste of the eternal kingdom. And this section of Luke’s gospel is filled with parables that focus on the kingdom.

Remember what I said about the Sabbath, before reading this passage? That it was a foretaste of the eternal kingdom. And this section of Luke’s gospel is filled with parables that focus on the kingdom. The surface meaning may have to do with avoiding embarrassment. A deeper meaning might be that we should humble ourselves. One of the challenges that Jesus had was his disciples wanting to grab key positions in the coming kingdom.

The surface meaning may have to do with avoiding embarrassment. A deeper meaning might be that we should humble ourselves. One of the challenges that Jesus had was his disciples wanting to grab key positions in the coming kingdom. But there is another way to look at this parable, which I had not considered until I read a blog post by a pastor in Iowa earlier this week.

But there is another way to look at this parable, which I had not considered until I read a blog post by a pastor in Iowa earlier this week. Instead of Jesus wanting us to show humility in the hopes that we might be called up to the head table (as you could read this passage), maybe Jesus is telling us to meet others where we find ourselves. Show hospitality to those less fortunate. If our only goal was to sit at the head table, we could easily display false humility to gain such a blessing.

Instead of Jesus wanting us to show humility in the hopes that we might be called up to the head table (as you could read this passage), maybe Jesus is telling us to meet others where we find ourselves. Show hospitality to those less fortunate. If our only goal was to sit at the head table, we could easily display false humility to gain such a blessing.  But Jesus wants us to long for the kingdom, which isn’t going to be made up of exclusively of those who look, and act like us. Jesus’ vision is for a world where believers cherish their friendship and fellowship with all people. It’s about us showing goodness to those who have no way to repay us for what we can do for them. Ponder what this kind of world might look like.

But Jesus wants us to long for the kingdom, which isn’t going to be made up of exclusively of those who look, and act like us. Jesus’ vision is for a world where believers cherish their friendship and fellowship with all people. It’s about us showing goodness to those who have no way to repay us for what we can do for them. Ponder what this kind of world might look like. You know, none of us know what this week will bring as Dorian churns up the waters. When Hurricane Matthew hit in 2016, I spent a few days in Dublin, GA. There’s a great hot dog shop there, not far from the courthouse, where I found myself drawn at lunchtime. There were the regulars, but there was also those of us in exile: from Savannah, from Hilton Head, from Brunswick and Saint Simons. The place was packed. Friendships were made as we were forced to share tables. Stories were told of shared experiences such as being in gridlock on the highway. There was a lot laughter. I image that’s how the kingdom will be. So, if we evacuate this week, and you find yourself in a strange land for a few days, don’t see it as a burden. Instead, take it as an opportunity to sample the kingdom. That’s what Jesus would have you do. Let us pray:

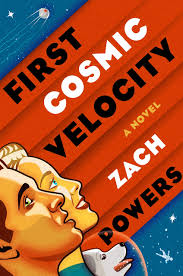

You know, none of us know what this week will bring as Dorian churns up the waters. When Hurricane Matthew hit in 2016, I spent a few days in Dublin, GA. There’s a great hot dog shop there, not far from the courthouse, where I found myself drawn at lunchtime. There were the regulars, but there was also those of us in exile: from Savannah, from Hilton Head, from Brunswick and Saint Simons. The place was packed. Friendships were made as we were forced to share tables. Stories were told of shared experiences such as being in gridlock on the highway. There was a lot laughter. I image that’s how the kingdom will be. So, if we evacuate this week, and you find yourself in a strange land for a few days, don’t see it as a burden. Instead, take it as an opportunity to sample the kingdom. That’s what Jesus would have you do. Let us pray: Zach Powers, First Cosmic Velocity (New York: Putman, 2019), 340 pages.

Zach Powers, First Cosmic Velocity (New York: Putman, 2019), 340 pages.