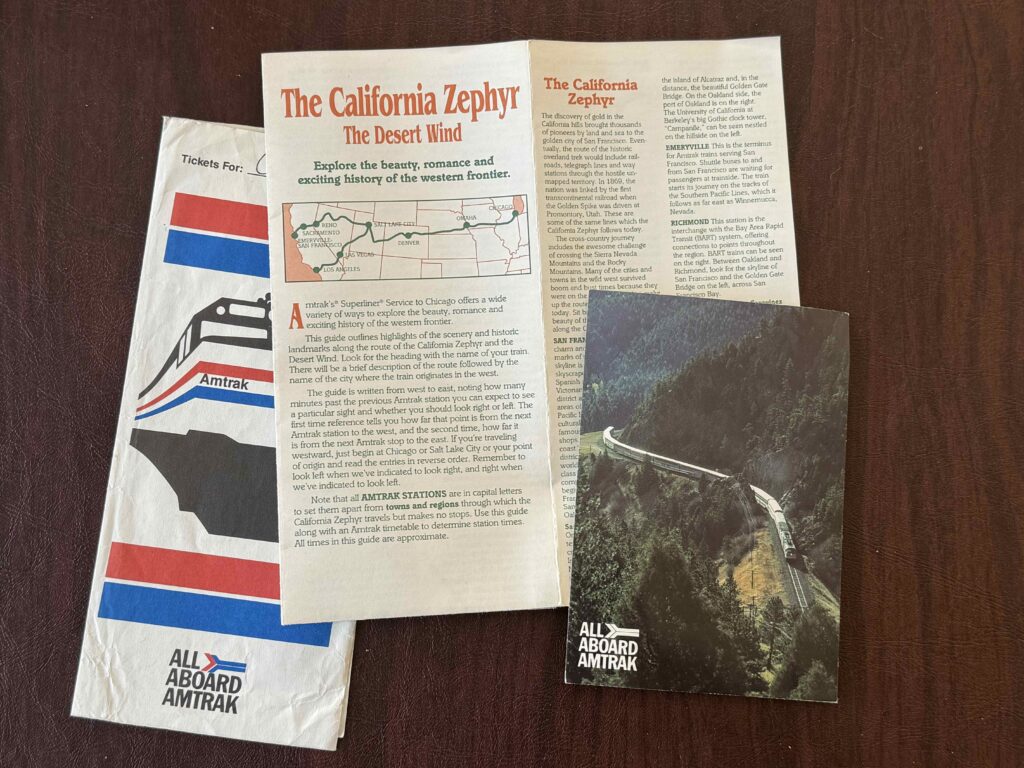

This piece is from my journals, memory, and the train guide for the California Zephyr. Sadly, I must not have taken as many photos as I do now, but then this was long before digital photography.

A three week break from Nevada

I left my car at Carolyn’s house in the Washoe Valley on the southside of Reno. We had an early dinner, then she drove me to the Reno Amtrak Station where we waited for the eastbound California Zephyr. It was the Tuesday after Easter, March 28, 1988. I checked my suitcases through to Pittsburgh, keeping with me only a small duffle bag which contained a pillow, blanket, toiletries, a few clothes, books, and snacks. The train pulled up to the station. It’s a short stop, just long enough for passengers to debark or step aboard. Carolyn and I hugged; I threw my duffle over my shoulders, grabbed the handrail and stepped up.

As I was finding my way up to the second floor of the double decked train, we pulled away. A few minutes later, we stopped in Sparks, for a longer stop so they could service the train. I looked out the window and saw Carolyn by the tracks waving. Knowing there was going to be this stop, she followed the train over. I waved back but couldn’t leave the train as I was waiting on the conductor to process my ticket. By the time he reached me, the train was running east alongside the Truckee River and passing the infamous Mustang Ranch. The train guide described the gaudy brothel only as “one of Nevada’s unique institutions.”

At this time, Amtrak had a promotional which allowed you to name your destination. You were allowed one additional stop each direction. The nation was divided into three zones. For 150 dollars, you could travel in one zone. For 300, you could cross all three zones. Looking to make the best of the offer, my destination was Fayetteville, North Carolina, three zones away. Going out, I would make a stop in Pittsburgh, where I would attend a lecture series and catch up with old friends. In North Carolina, I’d have a short visit with my parents, grandmother, and siblings. Coming back, I planned to stop in Seattle, cause I had never been there. I was a little scared but also excited about riding over 7,000 miles on the train over a three-week period.

I tried to do a little reading as I got use to my seat. While I brought several books with me, the reading was all heavy, mostly on theology and Biblical Studies. I had a commentary on the book of Revelation, a collection of Reinhold Niebuhr’s shorter writings, and Doris Lessings, The Summer before Dark. With daylight fading fast, I found myself unable to concentrate. I went to the restroom to brush my teeth and long before we stopped in Winnemucca, the rocking of the car and the occasional sound of the whistle blowing in the night had me asleep.

The previous week had been brutal

The past week had been brutal. The Wednesday before, I had officiated at my first funeral. It was for Lois Bowen, a longtime member of the church whom I had not met. Shortly after learning she had cancer, she left Virginia City and moved to Las Vegas to be near to family. They brought her back to the funeral, which I was to conduct. I don’t know how it all came together, but those who knew her shared with me pieces of her life and I somehow managed to work it into a homily.

The small sanctuary was packed for the funeral. Rudi, a former opera singer and a church member, sang a solo while Red, a local banjo picker in his 90s, played a wonderful rendition of “Amazing Grace.” When it was over, Pat Hardy, who served as my supervisor as I was only a student pastor, complimented me on having given one of the best funeral homilies he’d heard.

Then Holy Week kicked in. Thankfully, Pat came up to Virginia City again on Thursday to lead the Maundy Thursday service since I was not yet ordained and not allowed to officiate at the Lord’s Table. On Friday, I preached the ecumenical Good Friday service at St. Mary’s in the Mountains on John 19:17-20. The service went well except for the confusion which came in leading the Lord’s Prayer the “Presbyterian way” in a Catholic Church. (Presbyterians say debts instead of trespasses and the Catholics don’t have the doxological ending to the prayer). Also, on this day, I learned I had passed all four of the ordination exams I taken in February. A major hurdle toward ordination had been completed, but with two Easter Services, I had little time to reflect.

Then on Easter Sunday, two days before I stepped on the train, I held my first Sunrise Service at the cemetery on the north end of town. It was a cold morning. The temperature was in the 20s and a cold wind blew off Mount Davidson. We hurried through the service with me giving a short homily on Luke 24:1-12. Afterwards, we rushed back to the church on South C Street where Norm had coffee and pastries waiting for us. A few hours later, I conducted my first Easter Service, preaching on 1 Corinthians 15:19-26.

On the train

By the time I boarded the train two days later, I was exhausted. I don’t remember much after the Mustang Ranch and slept soundly to the rocking of the train.

In the dark, we passed Lovelock, Winnemucca, and Elko, towns I recalled from my drive the past Septemberfrom the Sawtooth Mountains to Virginia City. I woke at 4:30 AM. The train no longer rocked as we had stopped in Salt Lake City. I got off and walked around the platform in the cold. As we waited for another train, the Desert Wind from Los Angeles, I headed into the station and out onto the streets seeing if I could find a diner. It’d been a long time since dinner at Carolyn’s the evening before.

The streets were dark. Having only been to Salt Lake City once before, the previous summer as I drove west, I didn’t know where we were in relations to anything. When I came back to the station, I was ready to board the train and snooze again but was held on the platform as they hooked up the cars from Los Angeles. Once the cars clanged together, it was safe to board. Soon we pulled out from the station, heading south toward Provo. As we passed Geneva Steel, dawn was just breaking. The steel plant, with its furnaces glowing, made me feel as if I was already in Pittsburgh. I quickly fell back asleep.

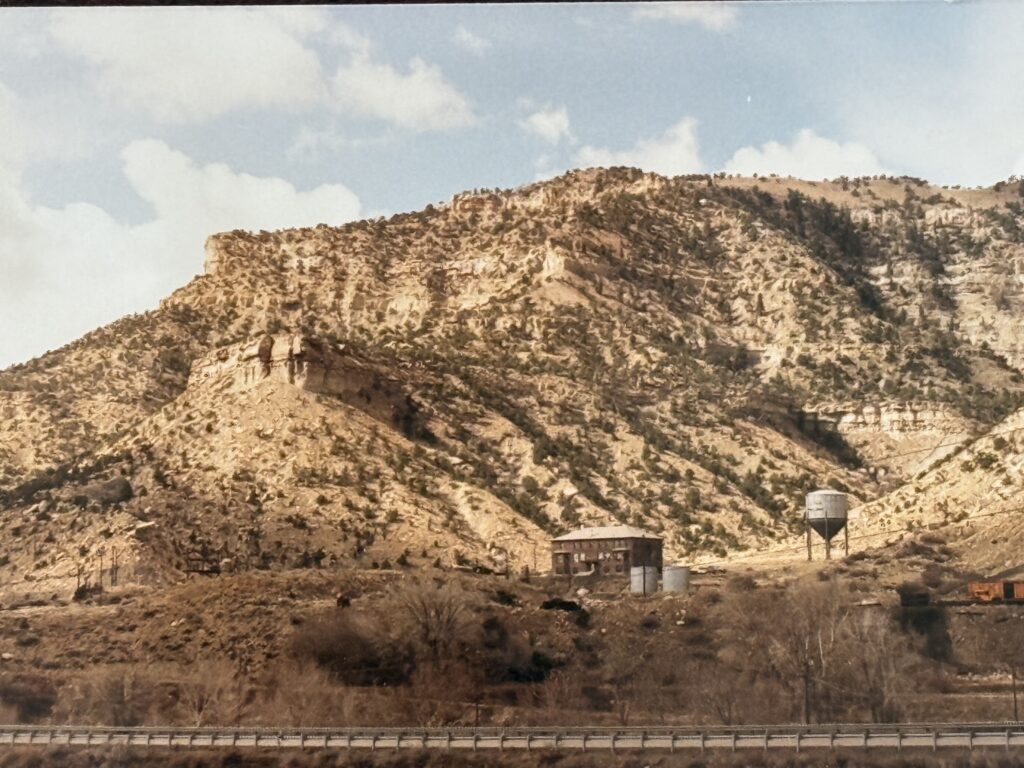

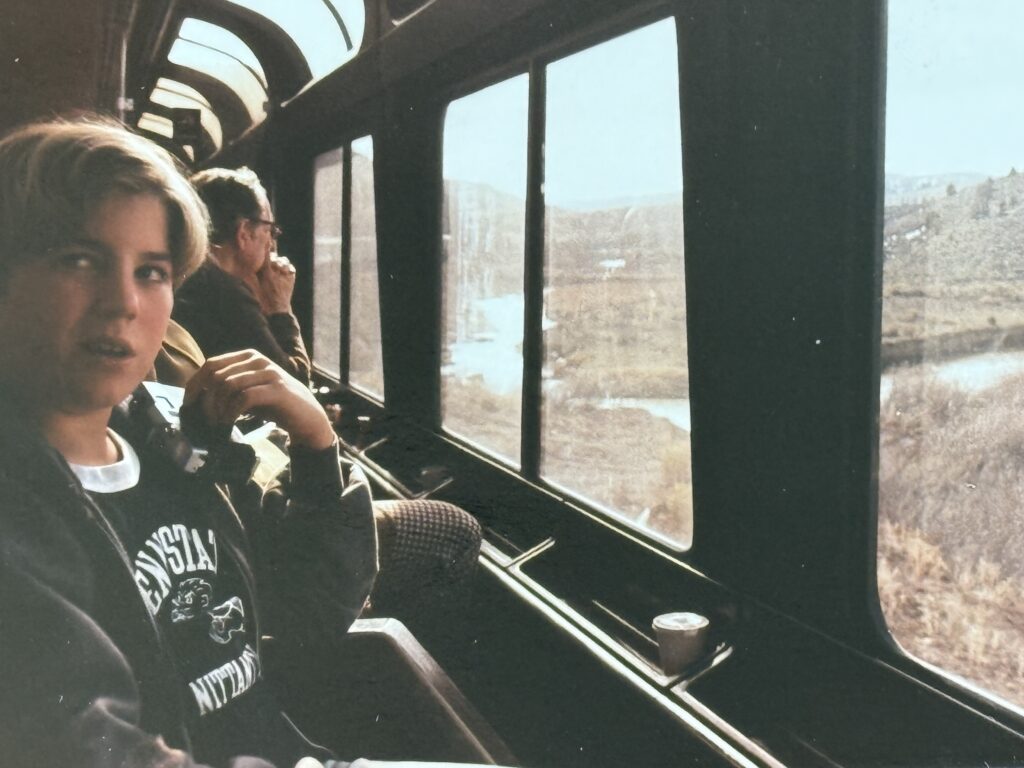

I slept through the stop in Provo. When I woke, the engines up front rumbled and the wheels squeaked as the train labored over the steep and tight curves heading up to up to Soldier’s Summit. I head to the laboratory to brush my teeth and wash my face, then back to the lounge car, where I picked up a cup of coffee. I would spend much of the day alternating between the lounge car and my seat in coach, and between looking at the scenery across the Utah desert and reading. Late morning, after the stop in Green River, and just before leaving Utah, the tracks began to parallel the Colorado River. We followed the river for the next 282 miles of stunning scenery, with stops at cute ski towns.

Leaving the Colorado River, we made a steep climb over the Rockies. Shortly after a stop at Winter Park, the train entered into darkness as we ran through the 6.2 mile long Moffat Tunnel. Coming back into daylight on the other side, we began our slow descend toward Denver as we ran through many tunnels.

Denver was another long stop on the train. I got to talking to an African American passenger on the platform, who was heading from his home in California to Cleveland, where he had family. We decided to see if we could find a place to get dinner and a drink. Not far from the station was a brew pub. This was still a new concept in 1989, with the only other one I knew of being back in Virginia City. We each ordered a sandwich and one of their brews. We consumed our food and drink quickly, making sure we didn’t miss the train when it headed out across the plains.

Day 2: Leaving Denver

Darkness was falling as the train left the station. I went to the lounge car where they were showing a movie, but it was crowded and I wasn’t interested, so I went back to my seat, got out my blanket and pillow, and quickly fell asleep.

Early to bed meant that I also woke early as we were rolling through eastern Nebraska. Knowing the lounge car didn’t open until 6 AM, I headed to the lavatory to clean up and brush my teeth. I got off the car for a few minutes when we stopped in Omaha and walked around in the platform. The sky was just beginning to lighten, and I could make out a few of the buildings. When the conductor called “All Aboard,” I went back to my seat and waited.

It wasn’t long before I saw the lounge car attendant heading from the crew quarters for the lounge, I followed him with my book, with the hope of getting some early coffee. When he entered the car, with me on his heels, he had a fit.

The lounge car attendant was an older African American gentleman who had spent his adult life working on the railroad. He was friendly, took pride in his work, and saw the lounge car as his kingdom. What he saw once he opened the door was a dozen or so dozen college students passed out on the floor and in the seats. Empty beer cans rolled from one side of the car to the other whenever the train went around a curve. He cussed and began nudging them with his shoe, telling them to get out of his lounge car. They slowly got up, rubbing their heads, and heading back to their seats. I helped him pick up the empty beer cans and clean up the tables as he gave me a lecture about what’s wrong with today’s youth.

The college students had been skiing over spring break and had boarded the train the day before in Steamboat Springs. He had been willing to sell them one beer each when he closed the car the night before, but it obvious they had a supply of their own as many of the cans were of brands not sold on the train.

That morning speed by. We stopped for a few minutes in Ottumwa, Iowa. It was a smoking stop, and all the smokers got off, lighting cigarettes as soon as they were on the platform. I got off to look around at Radar’s hometown. Radar, if you remember, was the loveable corporal on the TV series, “Mash.” At Burlington, Iowa, we crossed the Mississippi. The California Zephyr pulled into Chicago early in the afternoon.

A stop in Chicago, then onward to Pittsburgh

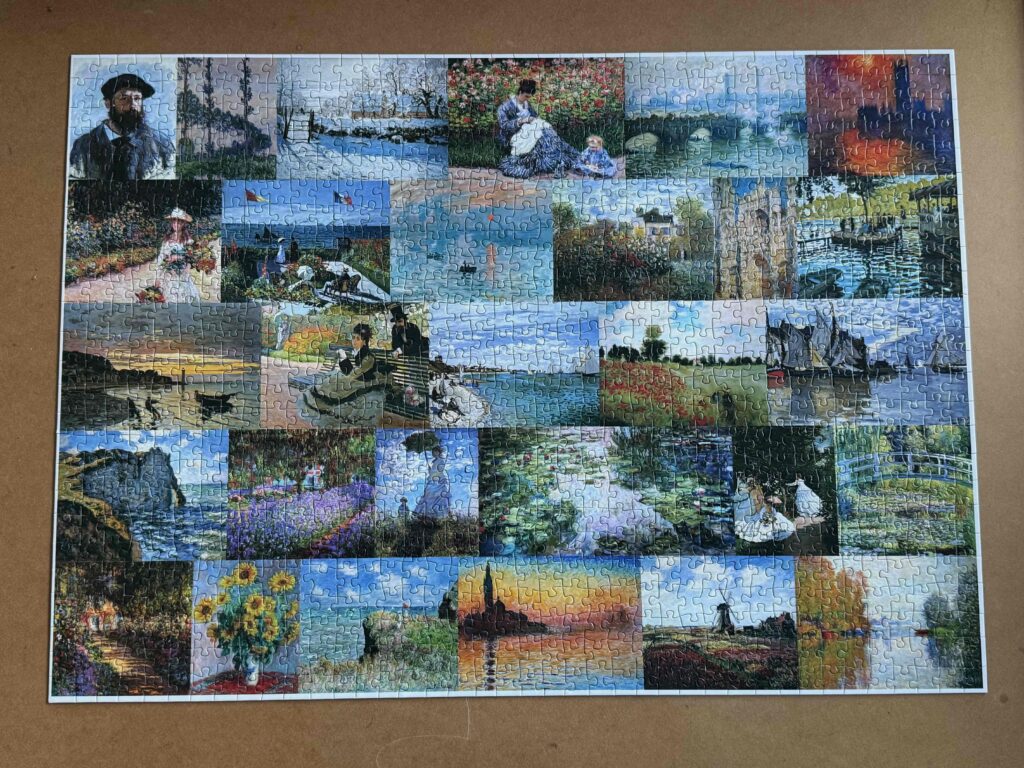

I had over five hours before catching the train to Pittsburgh, so I checked my duffle and walked across the Chicago River, down West Adams Street a few blocks, to the Chicago Institute of Art. There, I spent a couple of hours looking at paintings. To this day, I remember turning down a hall within the museum and looking at Grant Wood’s “American Gothic.” This was the first time I had seen the frequently parodied painting of a farmer with a pitchfork and his stern looking daughter standing in front of a gothic style house Wood’s had seen in Iowa. I was shocked by the small and unassuming size of the original. I’d always expected a much larger painting.

I left the museum around 5 PM, stopping at a bar and grill for dinner, before heading back to Union Station. Around 7, I boarded the Capital Limited for Pittsburgh. As we made our way around the south shore of Lake Michigan, through the steel mills of Gary, Indiana, it felt as if Pittsburgh was getting closer. Soon, I was asleep in my seat as we rushed through the upper Midwest. At 6 AM, we arrived in Pittsburgh. I gathered up my stuff and stepped off the train. Bill, a friend from the seminary, was there to meet me.

Other train trips of mine:

Coming home to Pittsburgh, 1987

Doubly late to West Palm Beach, 1986

Riding in the Cab of the V&T, 2013

Riding the International: Georgetown to Bangkok, 2011

Malaysia’s NE Line: The Jungle Train, 2011

Coming Home on the Southwest Chef, 2012

Other Virginia City Stories

Doug and Elvira: A Pastoral Tale

Easter Sunrise Services (a part of this article recalls Easter Sunrise Service in Virginia City in 1989)

The Revivals of A. B. Earle (an academic paper published inAmerican Baptist Historical Society Quarterly, part of these revivals were in Virginia City in 1867)