Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

September 22, 2019

Jeremiah 18:1-12

How many of you have a cabinet at home filled with Tupperware and other such plastic containers? (Raise your hands. Be honest). If your home is like mine, there are a variety of plastic stuff of all sizes. When it comes time to save left-overs, or to pack a lunch for the office, I can always find the size I need. Of course, I then struggle to find the matching lid, but that’s another story. Ponder for a moment what would our lives be like without such containers? How would we get by? Now let’s go back 2500 years.

You might be wondering about all this emphasis on pottery as we look at the Prophet Jeremiah. Pottery was a revolutionary technology in the ancient world. It allowed more movement as people could store things in pots, such as water and grain.[1] It provided a better way for cooking. No longer did our ancestors have to roast things over a fire like cavemen. They could make something tasty, adding herbs and spices and making broth. The pottery revolution was one of the great steps in human history that devolved to Tupperware. It allowed our ancestors to settle down. No longer did they have to wander from one source of water and food to another. They could stop and build cities. The potter played an important role in the ancient world. God often uses examples from everyday life to make a point, and with Jeremiah, it was the potter and his work. This morning, we’re visiting the potter’s house. Read Jeremiah 18:1-12.

You might be wondering about all this emphasis on pottery as we look at the Prophet Jeremiah. Pottery was a revolutionary technology in the ancient world. It allowed more movement as people could store things in pots, such as water and grain.[1] It provided a better way for cooking. No longer did our ancestors have to roast things over a fire like cavemen. They could make something tasty, adding herbs and spices and making broth. The pottery revolution was one of the great steps in human history that devolved to Tupperware. It allowed our ancestors to settle down. No longer did they have to wander from one source of water and food to another. They could stop and build cities. The potter played an important role in the ancient world. God often uses examples from everyday life to make a point, and with Jeremiah, it was the potter and his work. This morning, we’re visiting the potter’s house. Read Jeremiah 18:1-12.

Show Video of Lee Hyong-Gu, Ceramic Master https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RxpyG6ClIDU (3 minutes 20 seconds)

I love watching a potter shape clay. Don’t you?

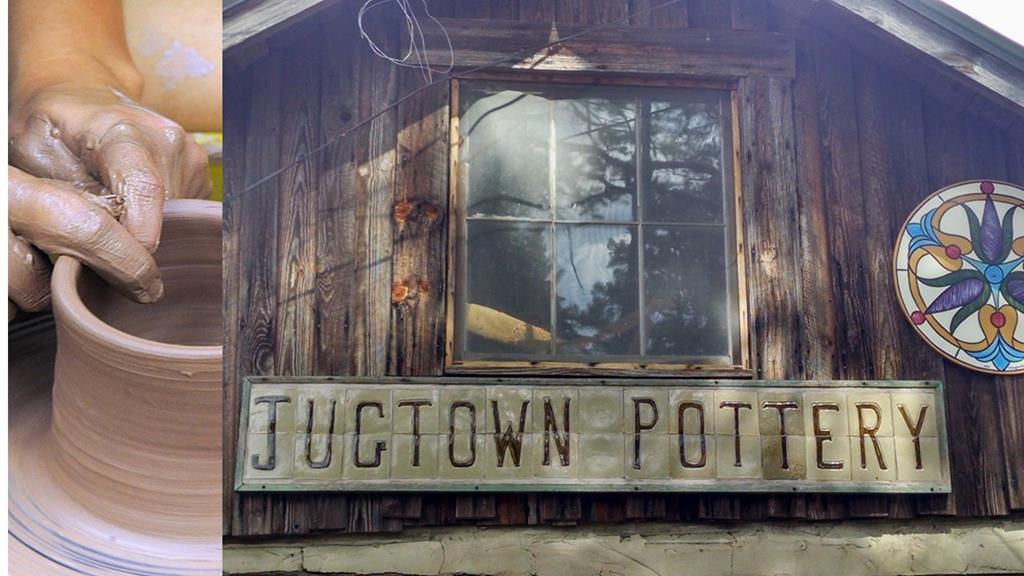

About twenty-five miles northwest of where I was born, where the Carolina Sandhills turn into clay hills, is a dot on the map known as Jugtown. It’s a place I like to visit when I am back in that part of the world. Today, the area around Jugtown and Seagrove is dotted with crafty potters who turn muck into beautiful and useful art. It’s a treat, as we’ve just seen on the video, to watch a potter turn a lump of clay on the wheel into something useful and beautiful.

About twenty-five miles northwest of where I was born, where the Carolina Sandhills turn into clay hills, is a dot on the map known as Jugtown. It’s a place I like to visit when I am back in that part of the world. Today, the area around Jugtown and Seagrove is dotted with crafty potters who turn muck into beautiful and useful art. It’s a treat, as we’ve just seen on the video, to watch a potter turn a lump of clay on the wheel into something useful and beautiful.

Jugtown received its name, as you can guess, from jugs. The law-abiding folks in the clay hills around there, I’m sure, intended their jugs to store molasses, honey, cane syrup, or something similar. Of course, it was also used to hold liquefied corn (also known as white lightning or moonshine). But with the advent of mason jars, such use of the jugs ceased. But early on, some of the potters had new ideas. In 1917, two of the potters began selling their wares in a store and tea shop in New York City. They emphasized utilitarian pots, things that could be used such as pie plates, crocks, mugs, and bowls. They stamped their unique mark on the bottom of each vessel. Over time, they began to teach new potters the craft and as one generation passed, another took up the wheel. Today, if you go to the area around Jugtown, you’ll find dozens or potters selling their wares. These artists have brought new life into that worthless clay that sticks to your shoes and gums up a plow.

Jugtown received its name, as you can guess, from jugs. The law-abiding folks in the clay hills around there, I’m sure, intended their jugs to store molasses, honey, cane syrup, or something similar. Of course, it was also used to hold liquefied corn (also known as white lightning or moonshine). But with the advent of mason jars, such use of the jugs ceased. But early on, some of the potters had new ideas. In 1917, two of the potters began selling their wares in a store and tea shop in New York City. They emphasized utilitarian pots, things that could be used such as pie plates, crocks, mugs, and bowls. They stamped their unique mark on the bottom of each vessel. Over time, they began to teach new potters the craft and as one generation passed, another took up the wheel. Today, if you go to the area around Jugtown, you’ll find dozens or potters selling their wares. These artists have brought new life into that worthless clay that sticks to your shoes and gums up a plow.

Finding a new purpose is sometimes helpful, and it could make a good moral of this story. But is it really what this passage is about? We need to remember that we’re not the potter, we’re the clay. Our purpose comes from the potter. And while, as this passage shows, the potter wields power over the clay, the clay might not always be suitable. If that’s the case, the potter starts over and creates something that works with the quality of the clay he has. In this passage we see God’s sovereign control, as a new type of pot is created. God’s in control, a fact we’re not always comfortable with.

Jeremiah is called to the potter’s house where God uses a common image of the ancient world to make a profound message. God’s word comes to him as he watches the potter over and over start off one direction with clay, and it not working, so he reworks the clay into something more suitable. This sounds hopeful. God will continue to work with us until we become a vessel that serves some purpose. One preacher, writing about this text, said that it demonstrates a sovereign God, “not a God of absolute capricious control, but a gracious willingness to change his plan to benefit his flawed people. When God discovers this fatal flaw in his people, he does not simply destroy them; he offers to start over.” [2]

Jeremiah is called to the potter’s house where God uses a common image of the ancient world to make a profound message. God’s word comes to him as he watches the potter over and over start off one direction with clay, and it not working, so he reworks the clay into something more suitable. This sounds hopeful. God will continue to work with us until we become a vessel that serves some purpose. One preacher, writing about this text, said that it demonstrates a sovereign God, “not a God of absolute capricious control, but a gracious willingness to change his plan to benefit his flawed people. When God discovers this fatal flaw in his people, he does not simply destroy them; he offers to start over.” [2]

But there’s a tension in the text that comes in verses 7-11. To make this passage to be only hopeful, we must cut the passage short and stop at verse 6. But that’s not fair to the text. Yes, there is hope in this passage, but the hope is offered to a repentant people who heed the warning that comes at the end of the passage. If they don’t heed the warning, the hope evaporates.

Jeremiah’s task is to preach impending judgment to God’s people. If they don’t shape up, if they don’t stop running around chasing foreign gods and idols, if they act like they’re in control and the God of the Universe is of no matter, they will be punished. Just as the potter can shape a vessel in a new way, they can be handled in a different manner. God can shape another nation to punish. There appears to still time, at this point, for the Hebrew people to change. Later prophecies of Jeremiah hold out no hope of repentance, but here, it’s not too late.[3] But time’s wasting. If they don’t hurry up and repent, it’ll be too late. And as we see in verse 12, the people don’t take Jeremiah’s words seriously. They follow their own plans and act in their own ways. God is not amused.

Jeremiah’s task is to preach impending judgment to God’s people. If they don’t shape up, if they don’t stop running around chasing foreign gods and idols, if they act like they’re in control and the God of the Universe is of no matter, they will be punished. Just as the potter can shape a vessel in a new way, they can be handled in a different manner. God can shape another nation to punish. There appears to still time, at this point, for the Hebrew people to change. Later prophecies of Jeremiah hold out no hope of repentance, but here, it’s not too late.[3] But time’s wasting. If they don’t hurry up and repent, it’ll be too late. And as we see in verse 12, the people don’t take Jeremiah’s words seriously. They follow their own plans and act in their own ways. God is not amused.

The message of this passage is that God has the power to reshape us, but we must let God work with us. If we resist God’s shaping, we may not be completely crushed, but we won’t fulfill the potential for which we were designed. The intention of our passage isn’t to be fatalistic and say we have no control. Instead, it’s a warning that we’re to work with God and not against him.

The message of this passage is that God has the power to reshape us, but we must let God work with us. If we resist God’s shaping, we may not be completely crushed, but we won’t fulfill the potential for which we were designed. The intention of our passage isn’t to be fatalistic and say we have no control. Instead, it’s a warning that we’re to work with God and not against him.

We often look at Scripture through our individualistic lens, and there’s no doubt that God has control over us as individuals, but it’s important for us to understand that this passage isn’t about a person, but about a people. God’s people. Today, we could apply this passage to the church. Those of us in mainline denominations often feel the church is being pulling apart. But using this analogy, we can see that perhaps the church is just being reshaped. If that’s the case, we need to look beyond our own perceived needs within the church, and to look where God needs the church within the world. That’s the hard task the Session has before it. It’s not what we can do to please the most people, but what we should be doing to join in God’s work.

When you leave this sanctuary today, ponder these questions: Where is God at work in the world? How can we participate? How can we be the clay that trusts the potter? Amen.

When you leave this sanctuary today, ponder these questions: Where is God at work in the world? How can we participate? How can we be the clay that trusts the potter? Amen.

©2019

[1] Eugene H. Peterson, Run with the Horses: The Quest for Life at Its Best, (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 1983), 76-77.

[2] Stan Mast, Old Testament Lectionary for September 2, 2019: Jeremiah 18:1-11” published by the Center for Excellence in Preaching: https://cep.calvinseminary.edu/sermon-starters/proper-18c-2/?type=old_testament_lectionary

[3] John Bright, The Anchor Bible: Jeremiah (New York: Doubleday, 1965), 124-125.

The campsites are rather expensive for pit toilets and no showers ($25/night), but we loved our site. It was just steps from the river and we had the place to ourselves. We slept to the sound of water running over rocks (augmented by the sounds of birds, frogs, insects, and the wind). It was a wonderful place to camp. And every evening, I took a swim in the river.

The campsites are rather expensive for pit toilets and no showers ($25/night), but we loved our site. It was just steps from the river and we had the place to ourselves. We slept to the sound of water running over rocks (augmented by the sounds of birds, frogs, insects, and the wind). It was a wonderful place to camp. And every evening, I took a swim in the river. After getting back and having a hurricane threaten, another full moon came around. This time, at home and on a semi-clear evening, I made the best of it by paddling around Pigeon Island (about 6 miles). It was a magical evening starting with incredibly red skies and then the beauty of the moon.

After getting back and having a hurricane threaten, another full moon came around. This time, at home and on a semi-clear evening, I made the best of it by paddling around Pigeon Island (about 6 miles). It was a magical evening starting with incredibly red skies and then the beauty of the moon.

Last week we learned of Jeremiah’s call by God as a prophet to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant.”

Last week we learned of Jeremiah’s call by God as a prophet to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant.”

In the spring of 2018, my sister, my father, and I took a trip to the Dry Tortugas. I’m sure many of you read the article I had about the trip in The Skinnie.

In the spring of 2018, my sister, my father, and I took a trip to the Dry Tortugas. I’m sure many of you read the article I had about the trip in The Skinnie. If you’re going to have a fort with a substantial garrison on an island without fresh water, you must find a way to overcome that limitation. The engineers who designed Fort Jefferson came up with a unique way to address the lack of water. They built a series of cisterns under the walls of the fort and designed a system to funnel rainwater into the cisterns where they provided water for later use. The fort could hold nearly two million gallons of water. It was thought there would be enough water and provisions within the walls for the fort to survive a yearlong siege.

If you’re going to have a fort with a substantial garrison on an island without fresh water, you must find a way to overcome that limitation. The engineers who designed Fort Jefferson came up with a unique way to address the lack of water. They built a series of cisterns under the walls of the fort and designed a system to funnel rainwater into the cisterns where they provided water for later use. The fort could hold nearly two million gallons of water. It was thought there would be enough water and provisions within the walls for the fort to survive a yearlong siege. But the plans of men and women often fail. This massive fort, built with millions of bricks and packed dirt, was so heavy that of the 136 cisterns, all but three cracked and allowed saltwater to infiltrate. They became useless.

But the plans of men and women often fail. This massive fort, built with millions of bricks and packed dirt, was so heavy that of the 136 cisterns, all but three cracked and allowed saltwater to infiltrate. They became useless. The cracked cistern image shows Israel’s condition after chasing after non-existent gods. As humans, we all need water. An image of God’s providence found throughout Scripture is that of living water nourishing us.

The cracked cistern image shows Israel’s condition after chasing after non-existent gods. As humans, we all need water. An image of God’s providence found throughout Scripture is that of living water nourishing us.

Friends, we don’t want to be cracked pots. We want to be vessels holding abundant living water that will quench our thirst, and can be shared to others, to quench theirs. Amen.

Friends, we don’t want to be cracked pots. We want to be vessels holding abundant living water that will quench our thirst, and can be shared to others, to quench theirs. Amen. Jeff Garrison

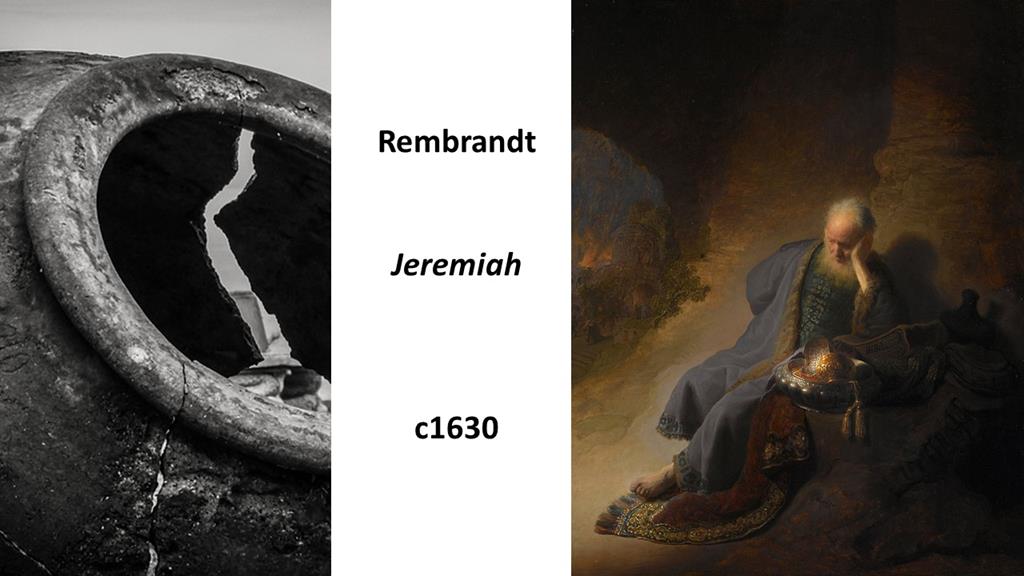

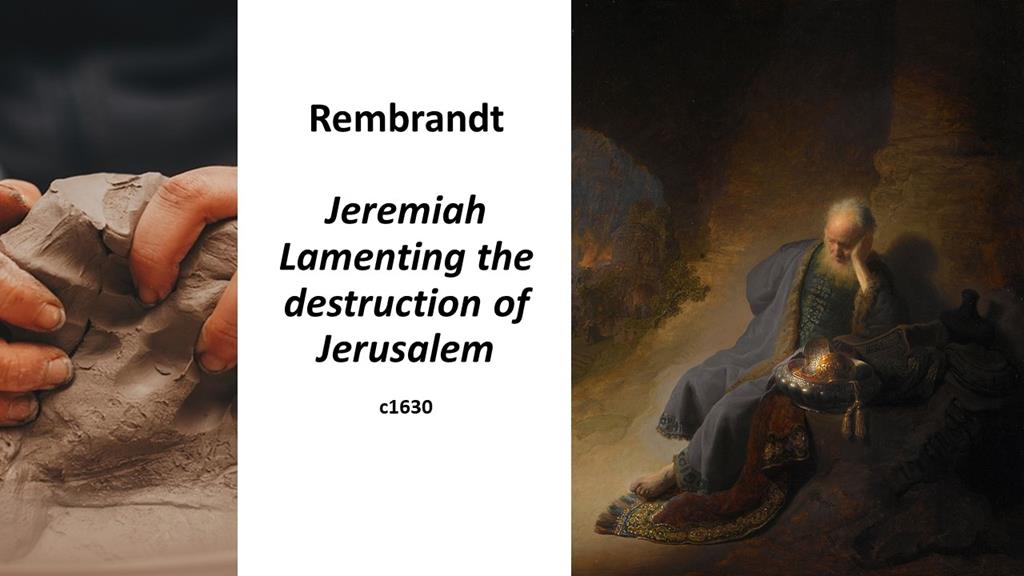

Jeff Garrison The prophet Jeremiah lived in interesting times. He was one of the longest serving prophets in Israel’s history, his calling coming as the Assyrians were losing power. It was a time of optimism in Jerusalem because they had existed as a vassal state under Assyria for over a century. It appeared they might be free once again, as in the years of Kings David and Solomon. Furthermore, Josiah, one of Judah’s few good kings, was implementing religious reforms. But then Josiah is killed in battle against Egypt.

The prophet Jeremiah lived in interesting times. He was one of the longest serving prophets in Israel’s history, his calling coming as the Assyrians were losing power. It was a time of optimism in Jerusalem because they had existed as a vassal state under Assyria for over a century. It appeared they might be free once again, as in the years of Kings David and Solomon. Furthermore, Josiah, one of Judah’s few good kings, was implementing religious reforms. But then Josiah is killed in battle against Egypt. We, too, are living in interesting times. Things are scary in our world: rogue nations having the bomb, individuals going berserk and killing people, terrorists creating political instability, and huge storms leaving behind chaos and destruction. The news often leaves us fearful and angry. And since we often don’t have answers for the problems we face, we blame others. Ben Sasse, a Senator from Nebraska, suggests one of the few things uniting us is our contempt for those of whom we assign blame. “At least,” we say, “we’re not like them.”

We, too, are living in interesting times. Things are scary in our world: rogue nations having the bomb, individuals going berserk and killing people, terrorists creating political instability, and huge storms leaving behind chaos and destruction. The news often leaves us fearful and angry. And since we often don’t have answers for the problems we face, we blame others. Ben Sasse, a Senator from Nebraska, suggests one of the few things uniting us is our contempt for those of whom we assign blame. “At least,” we say, “we’re not like them.”

Jeremiah was a bullfrog,

Jeremiah was a bullfrog, Back in early May, Gary Witbeck and I took a trip into the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. On our second night, we were camping on a platform at a place called “Big Water.” It’s the headwaters for the Suwanee River. As the sun set and evening descended, we watched alligators battle over territory (or maybe they were fighting over mates, or were flirting, we couldn’t tell the difference). While the gators fought, in the background a chorus of frogs sang. Their song would come in waves, starting up the river and working its way down and then back up. The frogs were in perfect harmony. You couldn’t tell one frog’s croak from another. It was quite beautiful.

Back in early May, Gary Witbeck and I took a trip into the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. On our second night, we were camping on a platform at a place called “Big Water.” It’s the headwaters for the Suwanee River. As the sun set and evening descended, we watched alligators battle over territory (or maybe they were fighting over mates, or were flirting, we couldn’t tell the difference). While the gators fought, in the background a chorus of frogs sang. Their song would come in waves, starting up the river and working its way down and then back up. The frogs were in perfect harmony. You couldn’t tell one frog’s croak from another. It was quite beautiful. But this is where the song gets it wrong. The one singing, claims to be a friend of Jeremiah, enjoying drinking his wine. But the Jeremiah of the Old Testament, was often lonely. He didn’t have many friends bellying up to him at the bar. Like a bullfrog, he cried out the message from God that he’s been given, and message that no one wanted to hear, so he was often alone and vulnerable. But he was faithful, and when we consider eternity, that makes all the difference in the world.

But this is where the song gets it wrong. The one singing, claims to be a friend of Jeremiah, enjoying drinking his wine. But the Jeremiah of the Old Testament, was often lonely. He didn’t have many friends bellying up to him at the bar. Like a bullfrog, he cried out the message from God that he’s been given, and message that no one wanted to hear, so he was often alone and vulnerable. But he was faithful, and when we consider eternity, that makes all the difference in the world. You’ll notice in the text that Jeremiah didn’t have a choice in all this. He was chosen by God before the foundation of the earth. Yesterday morning, in the Men’s Bible Study, we were reading Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, where are reminded that God calls us through Jesus Christ to do the work which has been prepared for us.

You’ll notice in the text that Jeremiah didn’t have a choice in all this. He was chosen by God before the foundation of the earth. Yesterday morning, in the Men’s Bible Study, we were reading Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, where are reminded that God calls us through Jesus Christ to do the work which has been prepared for us. Of course, like Jeremiah, we can beg off. Jeremiah said, “I’m just a boy.” Looking around, we might say, “we’re too old.” But God has heard that one, too. Remember Abraham and Sara? How old were they?

Of course, like Jeremiah, we can beg off. Jeremiah said, “I’m just a boy.” Looking around, we might say, “we’re too old.” But God has heard that one, too. Remember Abraham and Sara? How old were they? Jeremiah has been appointed for a mission. Likewise, the church has been appointed for a mission. We’re all called by God to follow Jesus and to point to him as our hope in a world that often seems hopeless.

Jeremiah has been appointed for a mission. Likewise, the church has been appointed for a mission. We’re all called by God to follow Jesus and to point to him as our hope in a world that often seems hopeless. Over the next six weeks, as we work through this series, we’ll be using images of potters. Our image today is a clump of clay, being kneaded like bread dough. The technical term for doing this to clay is “wedged.” The potter takes the clay and stretches and pushes it like a baker works dough. In doing this, all the air pockets are worked out so that the clay is easier to shape on the wheel and afterwards, when firing, the pot won’t have air pockets that’ll explode and destroy the vessel.

Over the next six weeks, as we work through this series, we’ll be using images of potters. Our image today is a clump of clay, being kneaded like bread dough. The technical term for doing this to clay is “wedged.” The potter takes the clay and stretches and pushes it like a baker works dough. In doing this, all the air pockets are worked out so that the clay is easier to shape on the wheel and afterwards, when firing, the pot won’t have air pockets that’ll explode and destroy the vessel. Paul, writing to the Ephesians, encouraged them to put away all bitterness, wrath, anger, wrangling, slander and malice. Such behavior is to be wedged out of us, like air is wedged out of the clay, so that we might be kind to one another, tenderhearted, and forgiving.

Paul, writing to the Ephesians, encouraged them to put away all bitterness, wrath, anger, wrangling, slander and malice. Such behavior is to be wedged out of us, like air is wedged out of the clay, so that we might be kind to one another, tenderhearted, and forgiving. Dorian is gone. It was more a “non-event” here. I ended up not evacuating even though I continued to watch the Weather Channel to see if things might change. But the storm stayed well off the Georgia coast. We received only a little wind and rain. I actually thought we had received very little rain, barely over an inch. Then I looked at the gauge again, 30 minutes later, and it was empty! The bottom of the gauge had sprung a leak. So I have no idea who much water we received. Our neighborhood also maintained power until we were on the backside of the storm. We lost it yesterday morning about 7:30 AM. I had to go out and dig into my camping equipment to fetch a coffee peculator. Since Hurricane Matthew (where I cooked on a camp stove on the front porch), we had replaced the electric stove top with gas. So, yesterday morning, I fixed corned beef hash, poached eggs, and coffee for breakfast, as you can see in the photo.

Dorian is gone. It was more a “non-event” here. I ended up not evacuating even though I continued to watch the Weather Channel to see if things might change. But the storm stayed well off the Georgia coast. We received only a little wind and rain. I actually thought we had received very little rain, barely over an inch. Then I looked at the gauge again, 30 minutes later, and it was empty! The bottom of the gauge had sprung a leak. So I have no idea who much water we received. Our neighborhood also maintained power until we were on the backside of the storm. We lost it yesterday morning about 7:30 AM. I had to go out and dig into my camping equipment to fetch a coffee peculator. Since Hurricane Matthew (where I cooked on a camp stove on the front porch), we had replaced the electric stove top with gas. So, yesterday morning, I fixed corned beef hash, poached eggs, and coffee for breakfast, as you can see in the photo.

This photo was taken at Delegal Creek last night as the sunset. Hurricane Dorian is several hundred miles south at this point. Today, as I write this, we have had a few bands of rain with wind, but nothing too bad. The storm should brush by us late this afternoon or in the evening, but will be staying off shore. Prayers to those in the Bahamas who suffered so greatly, and for those in the Carolinas who may experience more of this storm’s fury.

This photo was taken at Delegal Creek last night as the sunset. Hurricane Dorian is several hundred miles south at this point. Today, as I write this, we have had a few bands of rain with wind, but nothing too bad. The storm should brush by us late this afternoon or in the evening, but will be staying off shore. Prayers to those in the Bahamas who suffered so greatly, and for those in the Carolinas who may experience more of this storm’s fury.

At the end of the sixth grade at Bradley Creek Elementary School, there was a graduation banquet. It was held in the evening, which made it special, and in the cafeteria, which wasn’t so special. I’m sure we had macaroni and cheese. We always had mac and cheese. There must have been a rule that you couldn’t open the cafeteria without mac and cheese. But this was a special meal, so maybe there was a slice of ham or a piece of chicken and a piece of cake that was larger than the one inch cubes they fed us at lunch.

At the end of the sixth grade at Bradley Creek Elementary School, there was a graduation banquet. It was held in the evening, which made it special, and in the cafeteria, which wasn’t so special. I’m sure we had macaroni and cheese. We always had mac and cheese. There must have been a rule that you couldn’t open the cafeteria without mac and cheese. But this was a special meal, so maybe there was a slice of ham or a piece of chicken and a piece of cake that was larger than the one inch cubes they fed us at lunch. In the bulletin, I titled this sermon “Humility and Hospitality.” The problem with coming up with a title a few weeks before writing a sermon is that you often have no idea where the sermon is heading. I later decided that a better title might be Banquet Etiquette. But as I continued to study and ponder, I decided to put a question mark at the end. Yes, Jesus expects us to be humble and not pretentious. Such advice will also keep us from being in an embarrassing position. Yes, on the surface, this is about etiquette. But is this what Jesus is driving? Is this Jesus’ attempt to be the Emily Post of the first century? Or is there a deeper message here?

In the bulletin, I titled this sermon “Humility and Hospitality.” The problem with coming up with a title a few weeks before writing a sermon is that you often have no idea where the sermon is heading. I later decided that a better title might be Banquet Etiquette. But as I continued to study and ponder, I decided to put a question mark at the end. Yes, Jesus expects us to be humble and not pretentious. Such advice will also keep us from being in an embarrassing position. Yes, on the surface, this is about etiquette. But is this what Jesus is driving? Is this Jesus’ attempt to be the Emily Post of the first century? Or is there a deeper message here? Remember what I said about the Sabbath, before reading this passage? That it was a foretaste of the eternal kingdom. And this section of Luke’s gospel is filled with parables that focus on the kingdom.

Remember what I said about the Sabbath, before reading this passage? That it was a foretaste of the eternal kingdom. And this section of Luke’s gospel is filled with parables that focus on the kingdom. The surface meaning may have to do with avoiding embarrassment. A deeper meaning might be that we should humble ourselves. One of the challenges that Jesus had was his disciples wanting to grab key positions in the coming kingdom.

The surface meaning may have to do with avoiding embarrassment. A deeper meaning might be that we should humble ourselves. One of the challenges that Jesus had was his disciples wanting to grab key positions in the coming kingdom. But there is another way to look at this parable, which I had not considered until I read a blog post by a pastor in Iowa earlier this week.

But there is another way to look at this parable, which I had not considered until I read a blog post by a pastor in Iowa earlier this week. Instead of Jesus wanting us to show humility in the hopes that we might be called up to the head table (as you could read this passage), maybe Jesus is telling us to meet others where we find ourselves. Show hospitality to those less fortunate. If our only goal was to sit at the head table, we could easily display false humility to gain such a blessing.

Instead of Jesus wanting us to show humility in the hopes that we might be called up to the head table (as you could read this passage), maybe Jesus is telling us to meet others where we find ourselves. Show hospitality to those less fortunate. If our only goal was to sit at the head table, we could easily display false humility to gain such a blessing.  But Jesus wants us to long for the kingdom, which isn’t going to be made up of exclusively of those who look, and act like us. Jesus’ vision is for a world where believers cherish their friendship and fellowship with all people. It’s about us showing goodness to those who have no way to repay us for what we can do for them. Ponder what this kind of world might look like.

But Jesus wants us to long for the kingdom, which isn’t going to be made up of exclusively of those who look, and act like us. Jesus’ vision is for a world where believers cherish their friendship and fellowship with all people. It’s about us showing goodness to those who have no way to repay us for what we can do for them. Ponder what this kind of world might look like. You know, none of us know what this week will bring as Dorian churns up the waters. When Hurricane Matthew hit in 2016, I spent a few days in Dublin, GA. There’s a great hot dog shop there, not far from the courthouse, where I found myself drawn at lunchtime. There were the regulars, but there was also those of us in exile: from Savannah, from Hilton Head, from Brunswick and Saint Simons. The place was packed. Friendships were made as we were forced to share tables. Stories were told of shared experiences such as being in gridlock on the highway. There was a lot laughter. I image that’s how the kingdom will be. So, if we evacuate this week, and you find yourself in a strange land for a few days, don’t see it as a burden. Instead, take it as an opportunity to sample the kingdom. That’s what Jesus would have you do. Let us pray:

You know, none of us know what this week will bring as Dorian churns up the waters. When Hurricane Matthew hit in 2016, I spent a few days in Dublin, GA. There’s a great hot dog shop there, not far from the courthouse, where I found myself drawn at lunchtime. There were the regulars, but there was also those of us in exile: from Savannah, from Hilton Head, from Brunswick and Saint Simons. The place was packed. Friendships were made as we were forced to share tables. Stories were told of shared experiences such as being in gridlock on the highway. There was a lot laughter. I image that’s how the kingdom will be. So, if we evacuate this week, and you find yourself in a strange land for a few days, don’t see it as a burden. Instead, take it as an opportunity to sample the kingdom. That’s what Jesus would have you do. Let us pray: Zach Powers, First Cosmic Velocity (New York: Putman, 2019), 340 pages.

Zach Powers, First Cosmic Velocity (New York: Putman, 2019), 340 pages.

Why do we exist? What is our purpose in life? The Westminster Confession says we’re to enjoy and glorify God. That’s succinct. In Rick Warren’s best seller, The Purpose Driven Life, he expands this into five purposes. First, we are to love God. God wants us to open our lives up so that we might experience and be overwhelmed by divine love and in turn we might show our love to God. We call this worship. Our second purpose is that we’re created to belong to God’s family, which we know as the church. Within this new family, we are to be nurtured and to mature. This morning, I want us to consider our third purpose: to become like God’s Son. A big word for this is sanctification. We’re to become Christ-like. The fourth and fifth purposes are that we’re shaped to serve God and are made for a God-given mission.

Why do we exist? What is our purpose in life? The Westminster Confession says we’re to enjoy and glorify God. That’s succinct. In Rick Warren’s best seller, The Purpose Driven Life, he expands this into five purposes. First, we are to love God. God wants us to open our lives up so that we might experience and be overwhelmed by divine love and in turn we might show our love to God. We call this worship. Our second purpose is that we’re created to belong to God’s family, which we know as the church. Within this new family, we are to be nurtured and to mature. This morning, I want us to consider our third purpose: to become like God’s Son. A big word for this is sanctification. We’re to become Christ-like. The fourth and fifth purposes are that we’re shaped to serve God and are made for a God-given mission.

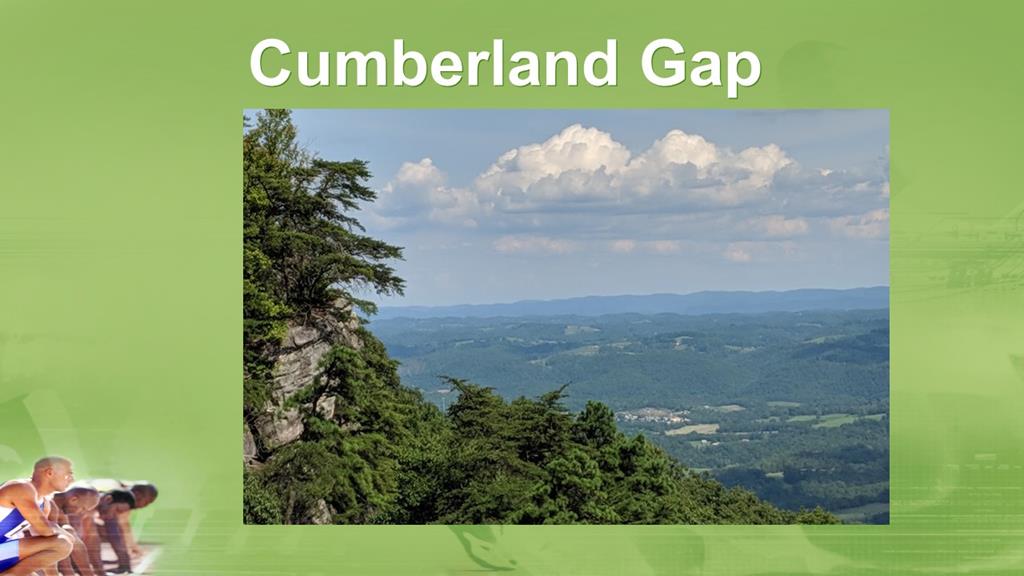

Last weekend, Donna and I were in Cumberland Gap, a significant place in American history even through it is mostly overlooked these days. This gap was the easiest place for settlers from the Carolinas to Southern Pennsylvania to make their way across the Appalachian Mountains. Today, we breeze through those mountains on engineered roads, but in the late 18th Century, those mountains stood like barricades, keeping people out. Then along came Daniel Boone, who built the Wilderness Road through the mountains and for the next hundred years, it was the easiest way to get into Kentucky and Tennessee and further west. It felt good to be there, riding bikes over the same terrain that Boone cut the road that began western migration. I’ve always liked Daniel Boone.

Last weekend, Donna and I were in Cumberland Gap, a significant place in American history even through it is mostly overlooked these days. This gap was the easiest place for settlers from the Carolinas to Southern Pennsylvania to make their way across the Appalachian Mountains. Today, we breeze through those mountains on engineered roads, but in the late 18th Century, those mountains stood like barricades, keeping people out. Then along came Daniel Boone, who built the Wilderness Road through the mountains and for the next hundred years, it was the easiest way to get into Kentucky and Tennessee and further west. It felt good to be there, riding bikes over the same terrain that Boone cut the road that began western migration. I’ve always liked Daniel Boone. My first lunch box had a photo of Fess Parker who played Daniel Boone in the TV show that was popular back during my childhood years. And you bet I watched it. When I was in the second grade, we had an opportunity to buy books from a flyer sent home from the school. It was fundraiser designed to raise money for the school and help get books into the hands of children. My parents allowed me to buy a book. I looked through that catalog and knew right away that the book I wanted. It was a biography, written on a child’s level, of Daniel Boone. On the day that it came, I looked through the book, but found many words I did not know so I took it to my mom, and she helped me read. One of the words that I seemed to have a hard time learning was “enemy.” I just couldn’t get it out. I had a mental block against this word and had to ask several times what the word was. Hard to imagine ever being that innocent, isn’t it?

My first lunch box had a photo of Fess Parker who played Daniel Boone in the TV show that was popular back during my childhood years. And you bet I watched it. When I was in the second grade, we had an opportunity to buy books from a flyer sent home from the school. It was fundraiser designed to raise money for the school and help get books into the hands of children. My parents allowed me to buy a book. I looked through that catalog and knew right away that the book I wanted. It was a biography, written on a child’s level, of Daniel Boone. On the day that it came, I looked through the book, but found many words I did not know so I took it to my mom, and she helped me read. One of the words that I seemed to have a hard time learning was “enemy.” I just couldn’t get it out. I had a mental block against this word and had to ask several times what the word was. Hard to imagine ever being that innocent, isn’t it?

How might we become more Christ-like? As I’ve already covered, the writer of Hebrews first suggests we strive to unburden ourselves of sin. As a runner, anything that holds us back can be a burden; so we should make sure we are not overwhelmed. We free ourselves of burdens so that we might run faster. Secondly, we’re to persevere. We are not perfect: there will be times we’ll trip, there will be times we fall, but like a good athlete, we brush ourselves off and continue. We must pace ourselves for it’s a life-long race. We don’t give up for we are after the prize. When our time here is up, we want to stand boldly before God’s throne.

How might we become more Christ-like? As I’ve already covered, the writer of Hebrews first suggests we strive to unburden ourselves of sin. As a runner, anything that holds us back can be a burden; so we should make sure we are not overwhelmed. We free ourselves of burdens so that we might run faster. Secondly, we’re to persevere. We are not perfect: there will be times we’ll trip, there will be times we fall, but like a good athlete, we brush ourselves off and continue. We must pace ourselves for it’s a life-long race. We don’t give up for we are after the prize. When our time here is up, we want to stand boldly before God’s throne.