As I work on Part 3 of my first transcontinental rail trip which I took in 1989, I brushed off this old piece I wrote about a short trip I took in 1985. The plan was to meet up with friends and head out for a two week hike along the Appalachian Trail. At this time, my only experience of trains had been in kindergarten, on Tweetsie (in the NC mountains which featured an attack by hostile natives and a hold-up by Butch Cassidy wannabes ), at 6 Flags, and in Japan.

I wait, my backpack resting against my thigh, and look up the tracks for the lights of Southern Crescent. The night air is heavy, warm and moist. The clock on the platform reads 1:30. We’re told the train is 30 minutes late. I tell Paula, a friend who drove me down to Gastonia, that she can go home if she wants. But she, like many of the others who have brought friends and family to the tracks, waits. We make small talk, mostly about my plans to hike for the next two weeks.

Finally, a light is seen in the distance, growing brighter. The locomotives blow by. It feels as if train will skip us. Then the metal wheels squeal and the train comes to a stop. An attendant steps off, sits out a step. Those of us waiting make a line and begin to climb aboard. I give Paula a quick hug and thank her again for the ride, shoulder my back and board. A minute later, the whistle blows, the attendant picks up the step. As he boards the train as the cars jerk and continue their southbound run through the night. Next stop, Spartanburg, but I’ll be asleep by then.

I stow my pack overhead and take a seat next to a man who’s already fast asleep. A few minutes later the conductor comes by and collects the $30 for my ticket. Back then, before internet and computers, you could still board and pay. I lean back my seat and close my eyes, attempting to sleep to the swaying of the car and the clicking of the wheels. Although tired, I’m also excited. I haven’t been on a train in the United States since I was a kindergartener. Then, my class rode the Seaboard Coastline from Southern Pines to Vass. Or Cameron? All I remember is that it was a mail train. We were treated to a tour the mail car where postal workers sorted the mail as it came aboard at each stop.

Tonight, I’ll ride a couple hundred miles through the Piedmont, from Gastonia to just north of Atlanta. I watch as we race through small towns, the lights of the crossbars and the stoplights blinking on deserted main streets. Finally, I finally fall asleep.

A few minutes later I wake up shivering. The AC is running full blast. The car feels like an ice box. I grab my sleeping bag from my pack, unzip it and wrap it around me for warmth and fall back asleep. A couple hours later, the attendant shakes me, informing me that my stop is next.

The guy next to me is awake and he asks if the lounge car is serving coffee yet. Not until 6 AM, he’s told. I stuff my sleeping bag into its bag and secure it back to my pack. Then I sit back down to wait.

I chat a bit with the guy beside me. He boarded the train in New York and is going home to Mississippi. He’s curious as to what I’m doing on the train with a backpack. I tell him that I’ll be meeting friends in Gainesville. And we’re heading up into the mountains to the beginning of the Appalachian Trail. He, too, grew up in the South. Like many African Americans of his age, he had to leave if he wanted decent work.

As he tells his story, I recall a photograph a friend of mine from the early-60s. Phil worked for the Charlotte Observer then. He caught on film the faces of three black boys looking out of the window of a northbound train. He titled it, “Chicken Bone Special,” based on the nickname the Southern Crescent at the time. The name came from how hardworking families from the Deep South, with little money in their pockets, headed north for work with a basket of fried chicken to tide them over.

The sky is pink when I step off the train at Gainesville. A sense of loneliness and abandonment washes over me as the train resumes its journey toward Atlanta, then Birmingham, Tuscaloosa, Hattiesburg and on to New Orleans.

I can tell right away that this isn’t the best part of town. The rails run between industrial buildings, many abandoned, with their dark windows reflecting the morning light. Those who got off the train with me are all met by friends and family. Soon, I’m the only one left. A cab driver asks if I want a ride. I tell him that I’d be meeting friends later in the morning. I ask if he knows where I can get some breakfast. He points to a diner down the street. I head off in that direction.

Entering, I’m aware of the stares, as drop my pack on one side of a booth and sit in the other. Most of those eating appears to have just gotten off their shift in one of the industrial plants by the tracks.

I order a big breakfast: poached eggs, corn beef hash, toast and coffee. As I eat, I pull out A Breakfast of Champions, by Kurt Vonnegut and begin to read. I stay, long after finishing my breakfast, drinking coffee and reading. It’ll be noon before Reuben, and his brother Bill, will arrive and pick me up at the train station. There’s plenty of time to kill.

I sit in the diner for a good 90 minutes, wanting the sun to get up above the horizon. Then I leave to see the town, walking away from the tracks. When I find a small neighborhood park, I place my pack against a tree, using it as a backrest, and sit, continuing to read. Later, as the stores open, I check out a couple of antique shops. It’s a safe hobby. I’m surely don’t plan to buy anything to add to my pack that already weighs 50 pounds.

I head back to the train station an hour early, thinking I can find a bench there to sit and read. But before I get to the station, I hear Rueben call my name from the passenger seat of a station wagon. He’d hired the janitor at his law office to drive him and his brother in his wife’s station wagon. I dump my pack in the back and crawl in the backseat next to Bill.

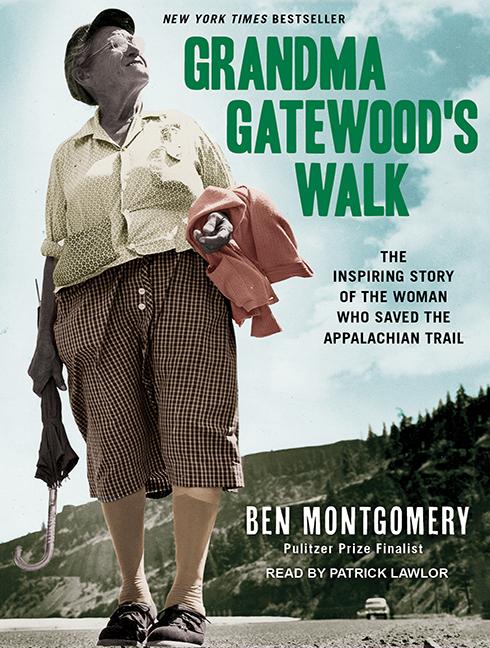

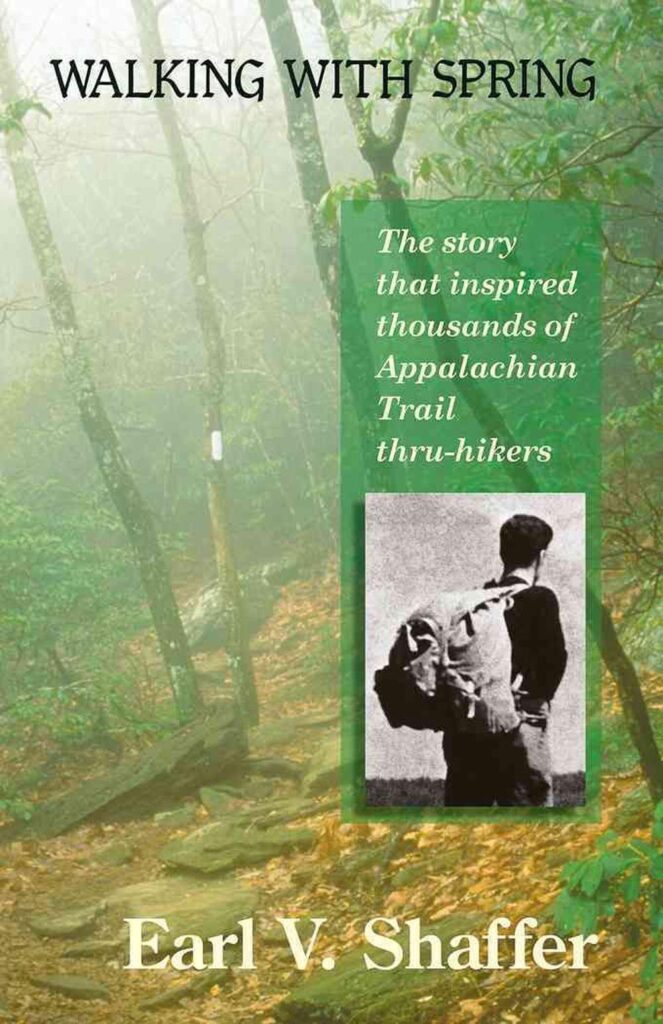

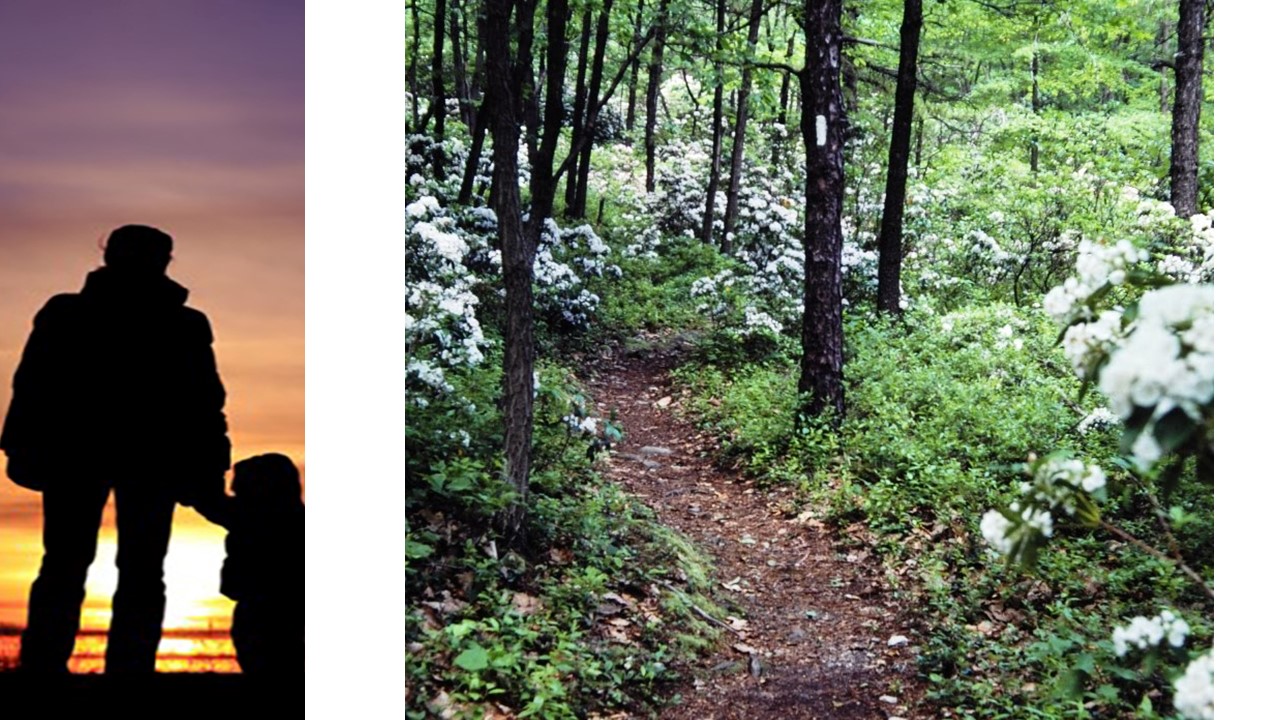

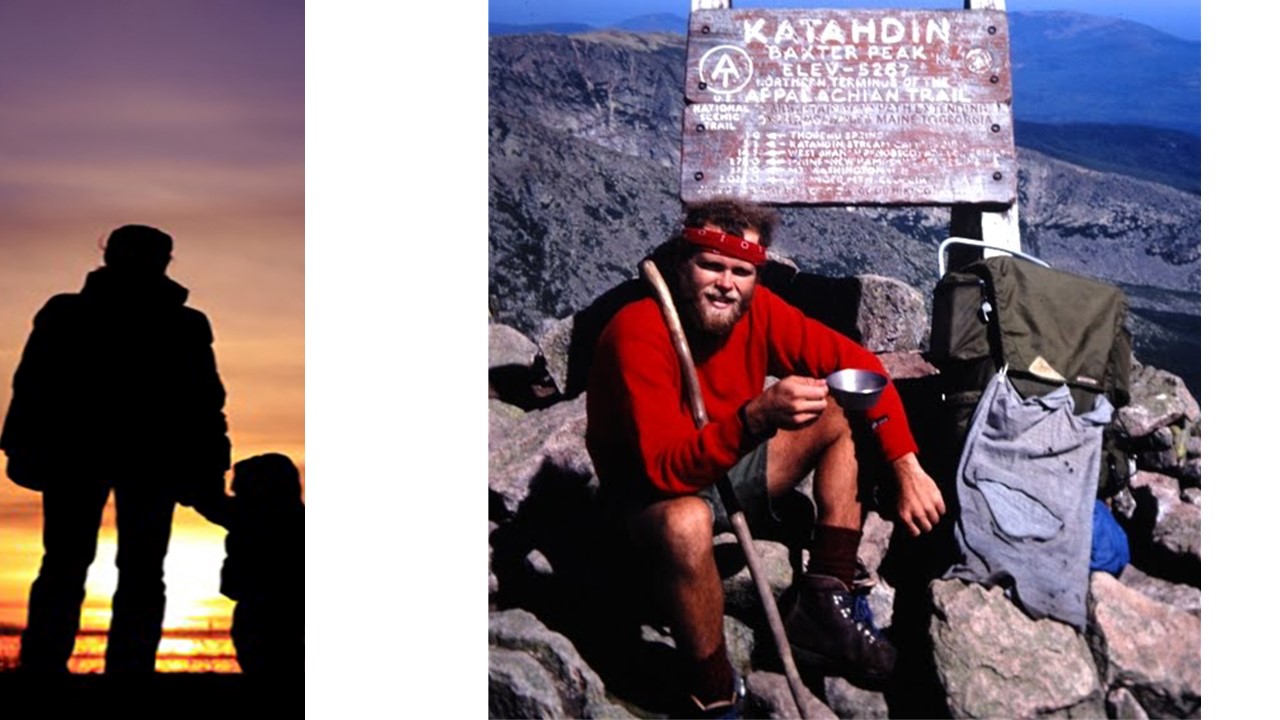

We make a short stop for burgers and then drive toward Amicalola Falls. The Appalachian Trail begins at the top of Springer Mountain, but it requires a hike to get to Springer. We skip the falls, as we take a Forest Service Road which drops us off a couple miles from the peak of Springer Mountain. We unload and say goodbye to our chauffeur, shoulder our packs and head off into the woods. I don’t stop till we get to the bronze plaque bolted on rock, identifying the summit. There, we stop long enough to take a few photos, and then head north, following the white blazes toward Maine.

Reuben and I are out for two weeks. We’re heading to Fontana Dam at the beginning of the Smoky Mountains. Bill, his brother, will hike with us the first week. He’ll get off the trail just south of the North Carolina border, where his wife will pick him up. She’ll also bring our resupply. This was Bill’s first trip, and it would be a tough one. For years afterwards, Reuben relished telling how, after he got off the trail, Bill called their mother and told her how Reuben, her other son, tried to kill him.

This passage is about us looking deeply and getting our priorities right. There are three connected proverbial thoughts here, which Jesus uses to encourage his listeners to evaluate their lives and to see where they are placing their trust. First, we’re not to trust worldly treasures for they have a way of disappearing. A fine wardrobe can be destroyed by moths, objects crafted out of metal can rust, and what’s to stop someone from stealing them when we’re not looking. Notice, however, Jesus doesn’t say that having nice things is bad. He just says we can’t trust them to always be there and that the problem with such niceties is that when we place too much trust in them, we risk not trusting God. Ultimately, our treasurers are going to fail us.

This passage is about us looking deeply and getting our priorities right. There are three connected proverbial thoughts here, which Jesus uses to encourage his listeners to evaluate their lives and to see where they are placing their trust. First, we’re not to trust worldly treasures for they have a way of disappearing. A fine wardrobe can be destroyed by moths, objects crafted out of metal can rust, and what’s to stop someone from stealing them when we’re not looking. Notice, however, Jesus doesn’t say that having nice things is bad. He just says we can’t trust them to always be there and that the problem with such niceties is that when we place too much trust in them, we risk not trusting God. Ultimately, our treasurers are going to fail us. The second proverbial through is about a “healthy eye.” My father just had cataract surgery this week and was telling me on Friday about how bright the colors are now that his eye is healthier. But Jesus isn’t making a pitch for eye surgery. Jesus listeners would have known right away what he was talking about when he mentioned an unhealthy or evil eye. They understood that an evil eye referred to an envious, grudging or miserly spirit, while a good eye connotes a generous and compassionate attitude toward life. One of my professors from seminary, in his commentary on Matthew, says it’s as if Jesus’ says: “Just as a blind person’s life is darkened because of an eye malfunction, so the miser’s life is darkened by his failure to deal generously with others.”

The second proverbial through is about a “healthy eye.” My father just had cataract surgery this week and was telling me on Friday about how bright the colors are now that his eye is healthier. But Jesus isn’t making a pitch for eye surgery. Jesus listeners would have known right away what he was talking about when he mentioned an unhealthy or evil eye. They understood that an evil eye referred to an envious, grudging or miserly spirit, while a good eye connotes a generous and compassionate attitude toward life. One of my professors from seminary, in his commentary on Matthew, says it’s as if Jesus’ says: “Just as a blind person’s life is darkened because of an eye malfunction, so the miser’s life is darkened by his failure to deal generously with others.” The next statement by Jesus concerns serving two masters. A slave would be run ragged if he had to answer to two masters. Likewise, if we try to serve both God and money, we find ourselves with two masters and the latter, money, makes a harsh master. There can never be enough. We need to place our priorities in order. We need to stick with God.

The next statement by Jesus concerns serving two masters. A slave would be run ragged if he had to answer to two masters. Likewise, if we try to serve both God and money, we find ourselves with two masters and the latter, money, makes a harsh master. There can never be enough. We need to place our priorities in order. We need to stick with God. It sounds too simple. “Store up your treasures in heaven; don’t worry about things here on earth.” Easier said than done, right? We all worry about having enough for tomorrow—and the day and the year and the decade that follows. We must admit that our prayers for daily bread seem unnecessary when we have a pantry full of food. When we have too much, it’s hard to depend upon God.

It sounds too simple. “Store up your treasures in heaven; don’t worry about things here on earth.” Easier said than done, right? We all worry about having enough for tomorrow—and the day and the year and the decade that follows. We must admit that our prayers for daily bread seem unnecessary when we have a pantry full of food. When we have too much, it’s hard to depend upon God. How might we learn not to store up our treasures here on earth? First, “Enjoy things, but don’t cherish them.” God created this world good and wants us to enjoy life and the blessings provided, but God gets angry when we see such blessings as being ours or being worthy of our worship. Second, “Share things joyfully, not reluctantly.” If it bugs you to share something you have with someone who needs it, you should then know that item has gotten a hold on you. It’s an earthly treasure, an idol. Finally, “Think as a pilgrim, not a settler.” “The world is not my home, I’m just passin’ thru,” the old gospel song goes.

How might we learn not to store up our treasures here on earth? First, “Enjoy things, but don’t cherish them.” God created this world good and wants us to enjoy life and the blessings provided, but God gets angry when we see such blessings as being ours or being worthy of our worship. Second, “Share things joyfully, not reluctantly.” If it bugs you to share something you have with someone who needs it, you should then know that item has gotten a hold on you. It’s an earthly treasure, an idol. Finally, “Think as a pilgrim, not a settler.” “The world is not my home, I’m just passin’ thru,” the old gospel song goes. Look inside yourself and use these thoughts to evaluate what you have: Enjoy, Share, and think like a pilgrim. A pilgrim is like a backpacker. Remember, you don’t want your pack to weigh you down. Amen.

Look inside yourself and use these thoughts to evaluate what you have: Enjoy, Share, and think like a pilgrim. A pilgrim is like a backpacker. Remember, you don’t want your pack to weigh you down. Amen.