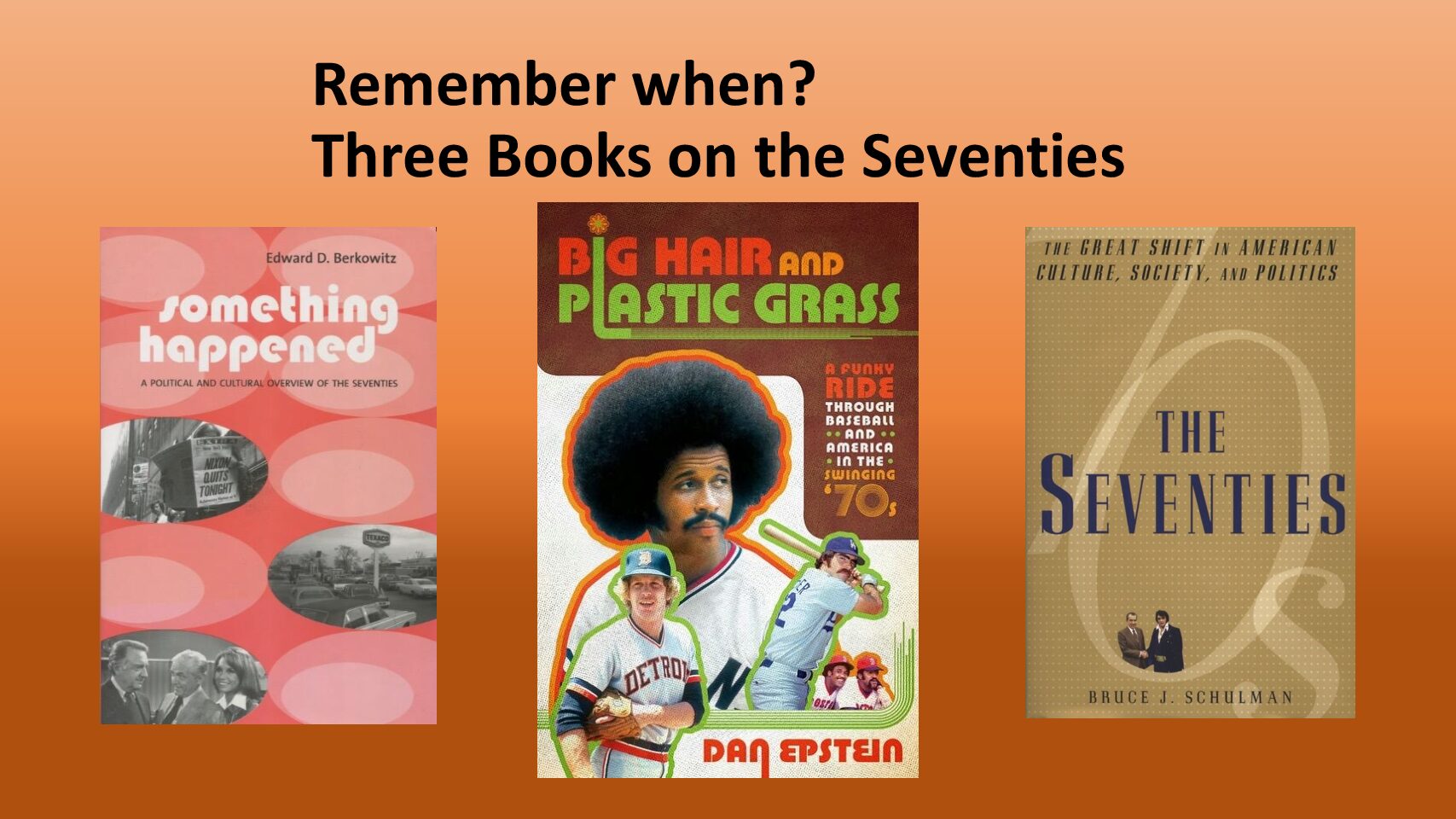

The 1970s was a pivotal decade for me. I became a teenager just two and a half weeks into the decade. By the time it ended, I had graduated from high school and college, began a short-lived marriage, and travelled halfway around the world. These three books describe a lot of what happened in the ‘70s. The first one, about baseball, I recently listened to while driving home from Pittsburgh. I wouldn’t become a fan of Pittsburgh until well into the 1980s, when I moved there to attend school. The other two books I read and wrote the reviews in 2008 and 2014 and are republishing them here.

Dan Epstein, Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging ‘70s

(2010, 2019 Blackstone Audible, read by the author), 12 hours and 54 minutes.

There were lots of crazy things going on in the 70s and this included baseball. Throughout the 60s, baseball remained conservative. As hair grew longer, ball players stayed clean cut with no facial hair. Drugs were shunned. Politics avoided. Oddly, which I didn’t know, the Detroit Tigers played a game while riots were burning much of the city just blocks from the ballpark. In the 70s, baseball caught up with society. I began listening to this book in my drive back from Pittsburgh the other week. It was a good book to listen to, as I had just watched the Pirates drop two games. In the 70s, the Pirates were often in contention, and they bookended the decade with World Series wins (1971 and 1979).

This book is probably not for everyone. The chapters deal with each season during the 70s, with chapters intersperse that deal with multi-year issues such as players hair, artificial grass, tight-fitting polyester uniforms, mascots, and promos that included cheap beer, wet t-shirts contests, and anti-disco events. It was a decade that saw a new dynasty rise and fall in Oakland. They will forever be remembered as the “mustache gang.” as they broke new barriers with facial hair. And then there were the Cincinnati Reds, who also set records with Pete Rose and Johnny Bench.

Baseball and Culture in the 70s

The 70s was a decade that saw many of the greats from the 50s and 60s retire as well as many long-term records broken such as Henry Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s homerun totals. While it was a decade that seemed to overcome many racial issues of the sport with the Pirates at one point having all nine players being of color. But there were still racial issues, especially as older ballplayers were looked over for coaching positions. It was the decade that saw George Steinberger enter the game as he purchased the New York Yankees. It also saw new teams emerge, including the first teams outside the United States as franchises began in Toronto and Montreal. And it was the decade in which players began to have more control over their livelihood and able to negotiate for better salaries and working conditions.

For one with roots in the 70s, there are a lot of good stories that I had vague memories of, and others that I didn’t know, but enjoyed listening to them being told. While I remember Roberto Clemente, it was nice to be reminded of his incredible 1971 World Series (he would die in a plane crash three months later while on a rescue mission for those suffering from an earthquake in Nicaragua). By the late 70s, I was no longer keeping up with baseball (I’d start again during the 80s), but it was nice to learn about Willie Stargell’s bringing together the Pirates for their last World Series in 1979, with “We Are Family” playing in the background.

Statistics

Of course, because this is book about baseball, you have statistics. Every chapter, and most paragraphs, contain numbers. My ears began to gloss over them (or would have glossed over them if I had read the book instead of listening to it). Hits, home runs, stolen bases, earned run averages, wins and loss, the numbers just kept coming and became a bit of a distraction. After a certain point, the numbers began to run together. Nonetheless, I enjoyed the book and the walk down memory lane. While I always admired Clemente, I came to also appreciate Willie Stargell for more than the stars placed in the upper deck of the old Three Rivers Stadium, where he’d launched homeruns.

My recommendation

Throughout the years of the 70s, there were many funny stories that today almost seem unbelievable. Such as 10 cent beer (what would go wrong with that?). Or a wet t-shirt contest in Atlanta. And then there was Doc Ellis pitching for the Pirates. In 1971, he threw what will probably be the only no-hitter ever pitched while high on LDS. And finally, at the end of the decade, a promo offered a discount for turning in a disco record at the turnstile. Late in the game, the vinyls were blown up which destroyed part of the field and led to an inside the park riot. Baseball, which had become respectful in the middle of the century, was a different game in the ‘70s.

A quote about Stargell

QUOTE ON THE 1979 WORLD SERIES: Stargell insisted on giving full credit to his teammates, but his teammates gave it all back to him. “He taught us how to take what comes and then come back,” Dave Parker said. “He taught us how to strike out and walk away calmly, lay the bad down gently, then get up the next time and hit a home run. From him we learned not to get too high on the good days or too low on the bad days, because there are plenty of both in this game…”

Edward D. Berkowitz, Something Happened: A Political and Cultural Overview of the Seventies

(New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 283 pages.

For Berkowitz, the 70s as an era ran from 1973 to Reagan’s inauguration in 1981. He cites ’73 as a beginning because so many things that helped define the era occurred that year: the end of American involvement in Vietnam, an Oil Embargo, and the crisis of a president that included the resignation of the Vice President (Nixon would resign a year later).

Berkowitz does a great job of describing the 70s. He reminded me of all the twist and turns we had in those turbulent years. We had a president who, by visiting China, changed the history of the world. I don’t think I realized how close we were to National Health Insurance in the early 70s. Sadly, this idea that died with Watergate and the economic downturn in ’74. And then we had a whole series of scandals. While it may have started Nixon and Agnew, they weren’t nearly as colorful as Wilbur Mills and his strippers.

From optimism to pessimism

The sixties were an optimistic decade; the seventies were pessimistic. In the 70s, according to Bruce Schulman, America was “made over.” Our “economic outlook, political ideology, cultural assumption and fundamental arrangements changed.” It was an era of declining productivity and extreme inflation. It was the era when much of the United States industrial strength started to slip and countries like Japan made great strides in their own productivity.

politics in the 70s

Politically, Berkowitz divides the seventies into political eras: the fall of Nixon, the Ford years, and the Carter years. Reading the book, I felt sorry for Carter. he inherited many problems. Berkowitz also points out Carter’s attempts at transparency made it harder for him to get things through Congress. Furthermore, Congress had new powers inherited from a weakened executive branch following Watergate. Carter was also the first post-World War II president not to have a period of economic growth. Then, just when it seemed his luck couldn’t get any worst, it did. His administration ended with Three Mile Island and the Iranian hostage crisis. Berkowitz notes that the problems Carter inherited and faced may have been beyond any politician ability to handle, but that Carter’s moralizing issues didn’t help and probably only made things worst.

According to Berkowitz (and others like Thomas Wolfe, whom he likes to quote), the 70s was the decade that everyone else began to demand rights. Women’s rights were at the forefront. 1970 saw the release of a new brand of cigarettes that focused on women. Virginia Slims came packaged with the logo, “You’ve come a long way, baby.” Much of the decade was also spent arguing over the ERA amendment. I hadn’t realized that the ERA passed Congress with the support not only of the left, but with right-winged senators like Strom Thurmond and Barry Goldwater. Berkowitz goes into detail on reasons why it failed. One reason was the economic downturn, which made people afraid of change. The other two major reasons were the political savvy of those against it, and the ERA debate framed around the abortion issue that moved to the forefront at the end of the decade.

Demanding of “rights”

In addition to women’s right, the 70s saw the rise of the gay movement, disability rights and rights of immigrants. In many ways, all the new groups demanding their rights paralleled a shift from the Civil Rights era, which spoke of doing what was good for all America, to a focus on more individual concerns. The 70s is seen as the “ME” decade, which helps explain the rise of Reagan in the 80s.

Growing up in the South in the 70s, I was shocked that Berkowitz discussed the integration of Boston’s public schools and spent little time talking about the integration of the schools in the elsewhere. Interestingly, the ruling which started busing wasn’t in Boston but in North Carolina (Swan vs Charlotte Mecklenburg, 1971). Three years later, this ruling was applied in Boston. As a Southerner who’s lived much of his adult life up north, I am still shocked at how segregated schools remain in th north. It seems strange that in upscale neighborhoods around northern cities, one can still find school districts that are mostly white.

Cultural changes

Berkowitz does a better job on describing the political changes in the s70s than the culture changes. Culturally, he explores only movies and TV in depth. Although he acknowledges significant authors like John Updike, he does not explore the role they played in defining an era. In movies, he focuses mostly on “blockbusters,” a new way of marketing movies in an era that was seeing declines at the theater. As for TV, the 70s were the golden years as they didn’t have competition from cable and other forms of media. He discusses not only sitcoms, but also news programs and sports.

Outside of a few brief mentions, Berkowitz does not discuss the role of music. Maybe it was because I spent most of the decade as a teenager, that I think that music defined the era. It was the era when “album stations” bucked the top-40 trend and migrated to FM. There, the airways were filled with the likes Bruce Springsteen, Pink Floyd, Fleetwood Mac, Steely Dan and southern rock. The last years of the decade was also, sad to say, the era of disco.

My recommendation

I enjoyed reading this book and recommend it; I just wished Berkowitz had gone further. He does a wonderful job discussing American politics. One final criticism, he overlooks lots of major world changes that were occurring, especially in Africa. Maybe the book should have been called a political history of the 70s in America

Bruce J. Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics

(Free Press, 2001), 352 pages.

I have a confession to make. I may need to do some serious penance. Reading this book, I realize in the 70s, I might have been a chauvinistic, misogynistic, homophobic racist. At the time, I just thought I hated disco and liked rock-n-roll. Mr. Shulman points to the errors in my thinking, suggesting those of us who shunned disco were guilty of a host of society’s evil (73-75). Or maybe I should revert to my redneck anti-elite ways and ask, “What do you expect from a professor in tweed from the Northeast?” Sadly, this makes me sound like Richard Nixon who hated the Northeast elite (24). Bruce Shulman, a disco loving Yankee, teaches at Boston University.

Despite what I said in my opening comment, I mostly enjoyed this book. I disagree with Shulman’s comments on disco and on how he looked disdainfully on the South. But if you can overlook his biases, he provides a good cultural and political history to the decade.

The 70s is often seen as a lost decade, squeezed between the optimistic 60s and the opportunistic 80s. Interestingly, as Shulman recalls, the 60s began with the Kennedy Camelot and ended with the widowed queen of Camelot (Jackie) marrying a rich Greek tycoon, twice her age (4). Shulman strives to interpret several wide cultural shifts occurring between 1969 and 1984. In this work, he explores music, books, television, movies, economics, and politics.

changes in the 70s

Several things happened during this decade. America lost a broad cultural consensus as the era of special interest groups gained prominence. Many of these groups were based on ethnic heritage. There a continual interest in African American culture held over from the 60s (the mini-series “Roots” premiered in the decade). Interest also included Hispanics, Italians, and Irish. The 70s also saw the rise of women’s interests with the ERA. As America began to gray, the elderly became a political force. Tip O’Neil, the Speaker of the House, was first referred to Social Security as the third rail in American politics. You touch it and die. Following up on the Stonewall Riots in the late ’60s, gay rights also gained ground.

In addition, there were shifts in regions. Shulman refers to the decade as the “Southernization of America” (256). Three were also religious shifts. Although religion became more important, it also became more personal and less able to lift a common vision for society. There were also changes in the American economy. The era gave rise to the “rustbelt” as factories in the northern part of the country closed. The inflation of the late 70s caused Americans to use more credit (why put off buying when it will cost more tomorrow).

Economic changes and the rise of the conservative movement

Also, due to regulation changes, Americans began to look at savings differently. Investing become more important than savings. Inflation ate up savings. And finally, the era saw the end of the old liberalism in American politics. No longer was the government seen as a force for the good with an obligation to help those unable to help themselves. Now, voices bemoaned any government involvement. Shulman discusses the tie between government involvement and civil rights in the 60s and how it took the decade for a new conservative collation to rise out of the old. Racial prejudices slid into the background as new conservatives found other issues to excite their causes.

my recommandation

Although I took offense at Shulman’s comments on those who disliked disco (as evident by my sarcasm), there is a lot to ponder on the role changes in religion, region, and race made to America during the decade. However, the nature of this book requires a certain amount of subjectivism, and one could draw different conclusions. That said, this is a good book for a trip down memory lane.

Jesse Cole, Find Your Yellow Tux: How to be Successful by Standing Out (Lioncrest Publishing, 2018), 303 pages, some photos.

Jesse Cole, Find Your Yellow Tux: How to be Successful by Standing Out (Lioncrest Publishing, 2018), 303 pages, some photos.

David Halberstam, Summer of ‘49, (1989, New York: HarperPerennial, 2002), 354 pages, with a bibliography, index, and some black and white photographs.

David Halberstam, Summer of ‘49, (1989, New York: HarperPerennial, 2002), 354 pages, with a bibliography, index, and some black and white photographs.