“We’ve lost a good friend, Jeff,” Terry said. It was late in the spring of 2010. I stopped by to see my Uncle Frank on his farm just north of Carthage. Terry, Frank’s oldest son, heard I was around and dropped by to see me.

I’d forgotten my cousin knew Charlie. Terry runs a company which rakes and ships straw from longleaf pines over the East Coast. Charlie’s wife had inherited a track of land, and my cousin harvested the straw off it. Terry told me about the old homestead near Cowpen Landing on the Northeast Cape Fear. Although I’d heard about the place, I’d never been there. My cousin told me the old house had fallen in, but the chimney still stood upright. Charlie had pointed out an indention in the brick where his mother-in-law sharpened the blade of her butcher knife. She ran the blade along the course brick till the blade was sharp. Then she would walk out to the smokehouse to cut off a slap of meat for dinner. Over the years, the metal of the knives carved into the brick.

I met Charlie at the Holsum Bakery. I hired on the summer I was nineteen, between my freshman and sophomore years of college. Charlie would have been almost sixty then. He spent most of life working for the bakery. You could always count on him to lighten things up with a good joke and you knew that any joke he told would be clean. Charlie worked hard but laughed even harder.

One afternoon, there wasn’t much to do as we’d run out of flour and the railcar, which was scheduled to be delivered that morning, had been delayed. We sat out near the loading dock where we could look down the tracks. Charlie came by and told us of growing up next to the railroad tracks, out north of the Green Swamp, east of Wilmington.

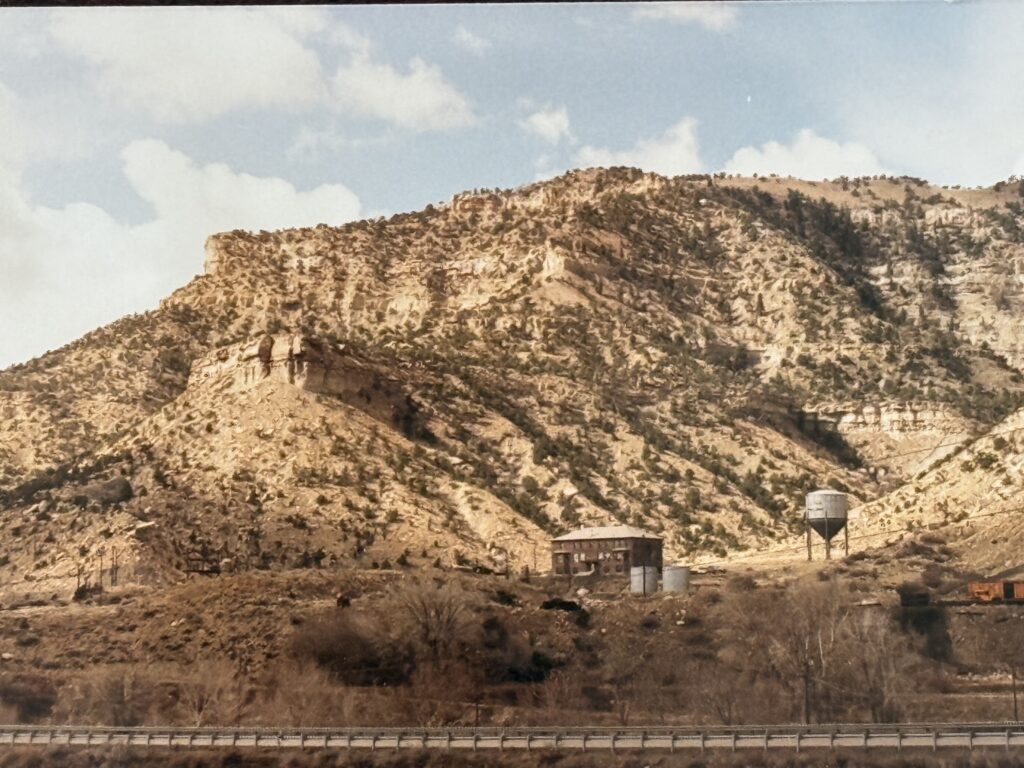

His daddy had been a section foreman for the Atlantic Coastline, maintaining the rails and water tower along a section of the mainline between Delco and Bolton. It may not look like much to those who speed by these days on the four-lane highway, US 74-76, but it’s a magical place. The land is as flat as a pancake and grows some of the most interesting plants on earth including the Venus flytrap. In some high sandy areas, higher by only inches, stately longleaf pines, and huge live oaks grow. In wetter areas, tupelo or black gum grow, often capped with mistletoe. And on the edge of swamps, often standing in water, are cypress, their sparse limbs dangled in Spanish moss. On cleared land in these parts, farmers raised tobacco and grew peanuts, along with strawberries and blueberries.

This is black-water country, water darkened by the tannic acid produced by the tupelo and cypress. Often, in the evenings when the air cools, fog develops over the waters, making it even more mysterious.

“Charlie,” I asked, “have you seen the lights?”

Just down the tracks from where Charlie grew up had been Maco Station. There, just a couple years after the Civil War, at a time the line was known as the Wilmington and Manchester Railroad, a brakeman named Joe Baldwin rode in a caboose. His car decoupled from the rest of the train and started to slow down. When Joe realized what happened, he grabbed a lantern and ran out on the back deck of the car. There, he swung his lantern back and forth, a universal sign on the railroad for trains to stop. He knew the schedule. Another train followed them.

Joe hoped to signal the engineer in time. But in the foggy swampland, the engineer didn’t see the signal until it was too late. The engine collided into Joe’s caboose, destroying it. Joe died; his head severed from his body. As they cleaned up from the accident, they never found the head and Joe’s body was buried without it. Most just assumed the head had rolled down the embankment and into the black waters filled with cottonmouths and an occasional alligator.

Shortly after Joe’s death, people started reporting a strange light moving in the swamps near the Maco sidings. Some suggested it was Joe’s lantern swinging along the tracks. A legend developed that Old Joe still looked for his head. People often went to these parts to walk the tracks to see the lights, but the tracks were removed in the late 1970s and not long afterwards, the highway expanded, and the lights fades away.

Charlie had seen the light, but he didn’t believe it to be Joe’s lantern. If I remember correctly, he brought into one popular theory that the lights were caused by swamp gas.

Living by the railroad tracks, hearing that lonesome cry from the engine pierce through the night as freight rolled toward the port in Wilmington must have been sealed in Charlie’s memory. But that lonesome wail can also bring sadness, as Charlie shared with us.

A year into the Great Depression, when Charlie was still just a boy, finishing up grade school, the lonesome wail wasn’t heard as much. There was so little freight moving that the railroad laid off every other section foreman. Charlie’s dad lost his job. The next day, Charlie went with his dad into Wilmington to look for work. But there were none to be found. Coming back home, late in the day, discouraged, they noticed smoke over the distant pines. As they got closer, they realized their house was totally engulfed in flames. The family lost everything.

Charlie’s life was forever changed. He went to live with family in Wilmington, where he worked hard and earned a little until the war came and he joined the Navy.

You’d think that after such hardships, Charlie would have been bitter. But there wasn’t a bitter bone in his body. He was one of the most joyous and positive individuals I’ve known. He wasn’t a bellyacher. Even when he had good reason to complain, he just shrugged it off.

About a year before I left the bakery, I was called into the General Manager’s office. I wasn’t sure what was up. When I entered, Charlie was there, along with the general manager, plant manager, and the president, who owned the bakery with his brother. It was obvious, they had been talking for some time to Charlie. At this point, Charlie’s responsibility included sanitation, receiving, and building maintenance. I was a production supervisor.

In the past six months, we had several problems in sanitation and receiving. When I entered, they informed me changes were being made. They assigned me Charlie’s responsibilities. Thankfully, they kept Charlie employed. He would continue to handle building maintenance but even there would report to me. It seemed strange for Charlie was nearly three times my age. I felt sorry for him, but he never showed any bitterness toward me.

Thinking about Charlie, I’m left to wonder why some people endure tragedy and disappointment and yet can still be joyful. He continued to maintain a positive attitude. In Charlie’s case, this partly had to do with his faith. Charlie knew he was loved by God. He found joy in creation, in life, in laughter, and in good friends.

My cousin met Charlie long after I had left the bakery “Charlie thought a lot of you,” Terry said. “He was always asking about you.”

Two weeks before Easter, 2010, and a month before Terry and I talked, Charlie died at the age 91. Hearing of his death, it seemed as if a part of my past died with him. Charlie was the one person from my time at the bakery whom I would occasionally see. After he retired, Charlie found a home in the church in which I grew up. Whenever I visited my parents, I would attend church on Sunday. Afterwards, Charlie and I would talk about old times.

Oh, how I wish I could talk to him again.

I haven’t yet been able to find any photos of Charlie. I wrote this in 2010, but edited and significantly expanded it for this post.

More Bakery Stories:

Coming of Age in a Bakery: Linda and the Summer of ’76