Jeff Garrison

Beaumont and Mayberry Churches

January 10, 2021

Hebrews 2

c2021

Introduction at the beginning of Worship

A lot has changed in our world since last Sunday when I announced we’d be exploring the book of Hebrews for the next few months. After the events in our nation on Wednesday, this is still a good book for us to explore.

I suggested last week the overarching message in this book is that it’s all about Jesus. As a Christian, our allegiance is to him alone. Jesus trumps Presidents, political positions, and even your favorite sports team. If Jesus is foremost in our lives, it makes a difference in how we act. I will come back to this in my sermon, but I want to state up front that its blasphemy to suggest that Jesus is with you if you’re willfully breaking the law, destroying property, and endangering lives.

Last week we explored the first chapter of Hebrews, where the author informs us that God is speaking in a new manner, through a Son. Then, the author makes the case that Jesus is superior to all the angels. It was important for Christ’s relationship with the angels to be established so that the author could make his next point, which we will get to in today’s passage.

Insights into Hebrews

Let me say a bit more about the Book of Hebrews. It’s a mystery. We don’t know who wrote it nor do we know its intended audience. A traditional letter would have given us such insights. Instead, from what can be induced from the text, it appears it was written to a congregation of Jewish Christians who are discouraged and may be considering returning to their former religious practices. In other words, they’re drifting away.

In the second and third century, it was suggested that Paul was the author, but even then, there were those who said that he couldn’t have been author.[1] However, the author of Hebrews, or the Preacher as I’ll refer to him, was familiar with Pauline theology.[2]

Parabola of Salvation[3]

Both Paul and Hebrews outlines a parabola of salvation. You see this most clearly in the second chapter of Paul’s Letter to the Philippians, where he cites the “Christ Hymn.” To summarize: Christ being the very nature of God, didn’t consider equality with God something to be used for his advantage. He humbles himself, taking on the role of a servant, becoming obedient even unto death, and for this reason he is now exalted and given the name above all names.

Hebrews has a similar outline. Christ starts in heaven (he was at creation as we saw last week). He lowers himself to our level (lower than the angels) and now because of his faithfulness, he is at the right hand of God the Father and is to be worshipped above all.

After the reading of the Scriptures

I have known several families who have adopted children from overseas: from China, Russia, and Vietnam. Today, there is less such activity, but back in the 90s, a lot of people were adding to their family through such adoptions. The parents would have to leave the United States and travel overseas. In many cases, they had to stay in the country for several weeks. There was paperwork. They had to be investigated. They had to demonstrate their abilities to support and care for the child. Only then were they able to take the child home with them, where they raised the child as their own.

Our adoption

While I would never suggest you think of these parents as Jesus, even though the ones I know are believers, I tell you this story as an analogy to the flow that the preacher in Hebrews uses to show the salvific work of Jesus Christ. He comes from heaven, from the throne of God, and assumes a position lower than the angels. Psalm 8 is quoted here, where we’re reminded that we’re created a little lower than angels.[4]

Like these parents who made the trip to adopt a child, Jesus makes the descent from heaven to earth to adopt us (the descendants of Abraham). He destroys the power of death and breaks the power of the devil. Now he can serve as our “high priest,” (which is a recurring them within this book[5]).

Because Jesus knows the troubles we face; he can help us in our trials and tribulations.

Now, if we look back to the beginning of this chapter, we’re reminded of the task at hand for the Preacher of Hebrews. He tells his audience not to drift away, but to pay attention. It’s all about Jesus. Our only hope is in the work God is doing in the world.

A Peek at the Work of the Trinity

In the first four verses, the Preacher references the activity of all three persons of the Trinity. While he’s talking about what Jesus has done through the incarnation, by coming in the flesh, he links this to God the Father, who sends the Son. Following the Son’s work, the Holy Spirit steps up to provide us with the gifts we need. While it doesn’t say so here at the beginning, later in the book, we’ll see that the purpose of our calling is to participate in God’s ongoing work in the world.[6]

Jesus’ work

But to be able to do our work in the world, Jesus has to first do his work. And Jesus’ work is to save. But we should ask “save us from what?” The end of this chapter tells us that Jesus saves us from the fear of death and the bondage of the devil.[7]

Furthermore, it’s telling what we’re not saved from. We’re never told that Jesus saves us from hardship or pain or disappointment. Instead, because Jesus experienced all those things, he’s in a position to help us.

You know, if you were lost out in the woods, who would you want as your companion? Would you want the smartest person in the world or one who has lived in the wild? I think most of us would pick the later. We’d want firsthand knowledge. Jesus is like that; he knows what we’re facing.

Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen

There is a wonderful spiritual titled Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen… It’s slave music. The lyrics cry the blues. There’s troubles and sorrows and pains. The singer longs for glory in heaven. That’s where he or she finds hope. But there is one line in the fourth verse of Mahaila Jackson’s arrangement of this spiritual that I want you to hear… It goes, “Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen. Well, no, nobody knows but Jesus.”

Nobody knows, but Jesus. He knows our troubles. He knows what we endure because he’s also endured it.

The Events at our Capitol on Wednesday

Now let me say something about the idea of Jesus’ saving. As it was with many of you, Wednesday afternoon, I was sad watching the invasion of our national Capitol. But I was even more offended by a few who carried signs invoking Jesus’ name and at least one person waving a Christian flag.

One of the signs read “Jesus Saves.” I found myself wondering what such a statement means in riot. And furthermore, I wondered what such a sign said to those watching the event? If a non-Christian witnessed that event, would they see the sign and think, “Oh gee, I got to get right with Jesus.” I don’t think so. Instead, it probably helped inoculate them against the faith. “I don’t want to be one of them!” they’d think.

Jesus and Insurrections

We need to remember that in his earthly ministry, Jesus refused to take part in an insurrection. He told Peter to put away his sword. He didn’t call on the angels to take him off the cross. He was willing to endure everything we might endure, this passage suggests, so he could have empathy with our situation.

As Christians, we do not get to co-opt Jesus to our side. To suggest Jesus is only on our side of an issue is to commit blasphemy. When it comes down to it, what is important is not that Jesus is on our side but that we’re on Jesus’ side. We don’t get to pick Jesus, we can only be chosen by Jesus.

Where Goodness Still Grows

This week I finished reading a good book. Where Goodness Still Grows, by Amy Peterson, is a critique of how parts of the evangelical church have shifted away from a Biblical foundation. Having grown up in such a setting, she draws on her life’s experiences. One of the stories she tells is an attempt by her and her husband to help a troubled young woman whom they allowed to live in their home for a year. She was disappointed that this woman only attended church with them once or twice. She writes:

“Again and again I had to confess to God how much I wanted to save her—to make everything right for her. Again and again God reminded me that saving people was God’s job. My job was to open the doors of my home and my heart.[8]

This part of the book of Hebrews is steeped in theology. But the Preacher of this sermon, that we know as the Book of Hebrews, will later bring his argument back to what we should be doing because of what God through Jesus Christ has done for us.[9] Yes, Jesus saves. We do not save! However, our lives must be lived in a manner that points to Jesus and helps people to understand what God has done in his life, death, resurrection and ascension.

If you’re like those to whom this message was originally addressed, drifting away from the faith, you need to catch, once again the vision God has for us and for our world. For there is only one way, as is pointed out in verses two and three, to keep from having to the pay the penalty of our transgressions and disobedience. That way is through Jesus Christ. Amen.

Pastoral Prayer

God of the ages, you have watched nations and empires rise and fall. You have witnessed our attempts to do what we think is right and good, only to fail and to hurt others and dishonor you. We want to be in charge. We fail to realize that history is in your hands.

Those of us who claim to follow Jesus are outraged by the violent attacks on nation’s Capitol, along with many of our state Capitols. Yet, we know there have been times we’ve failed to live up to your standard. Forgive us and help us to avoid hateful and inciteful rhetoric in our speech. Give us the understanding to seek the truth in all things, the boldness to stand for justice, and the humility to be gracious to those with whom we disagree.

We are concerned for the well-being of those who serve in Congress as well as members of their staff, and the police officers who are charged with keeping them safe. We pray for our nation as we move through this rocky transfer of power. We ask that the violence stop, that rational minds prevail, and that those who hold political offices might use their position of authority to offer hope during this dark time in which there is so much distrust and fear.

Amidst the trouble we’re facing is the pandemic. The numbers of those who have died and those who are in the hospital are no longer forefront in our eyes as we focus on our nation’s political trouble. But the numbers continue to rise, even in our community. We pray, O God, for this to end, for the vaccine to become available more quickly, and for all of us to do what we can to protect others. Comfort the many who grieve over the death of love-ones. Bring healing to those who suffer from this disease and all other illnesses. Give solace to our stressed and overworked health-care workers. Keep those on the front lines of this pandemic safe.

With all the uncertainty, our economy continues to suffer. After months of job growth, we lost jobs last month as more industries suffer from the effects of the pandemic. Be with those who are struggling economically and help us all, Lord, to compassionately do what we can to help our neighbors in need.

Yet, despite the troubles we face, we are grateful for your love and for the beauty that surrounds us. We have been blessed this week with incredible sunrises and sunsets. We give you thanks for friends and family and for Jesus, who adopts us into his family. We are blessed by the church. Help us, O God, to count our blessings and to live gratefully and graciously. This we pray in the name of Jesus Christ… Amen.

[1] While the letter was accepted into the canon as Pauline, there were those from an early date, such as Origen, who accepted the letter into the canon, but didn’t think Paul was the author. See Luke Timothy Johnson, Hebrews (Louisville, KY: WJKP, 2006), 3-4.

[2] The idea of referring to the author of the book belongs to Thomas G. Long, Hebrews (Louisville, KY, JKP, 1997).

[3] Long, 26-28.

[4] While the author of Hebrews only says, “someone testified somewhere”, the quote is from Psalm 8:4-6.

[5] Starting with Hebrews 4:14 and continuing for the next six chapters, the author discusses the role of the high priest.

[6] See especially Hebrews 13.

[7] Hebrews 2:14.

[8] Amy Peterson, Where Goodness Still Grows: Reclaiming Virtue in an Age of Hypocrisy (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2020), 61.

[9] Chapter 12 and 13 focuses on following Jesus’ example and serving in a manner that is pleasing to God. Throughout the book, the author mentions the need of us to persevere in the faith. See 2:1-4, 6:1-12, 10:19-39.

Jeff Garrison

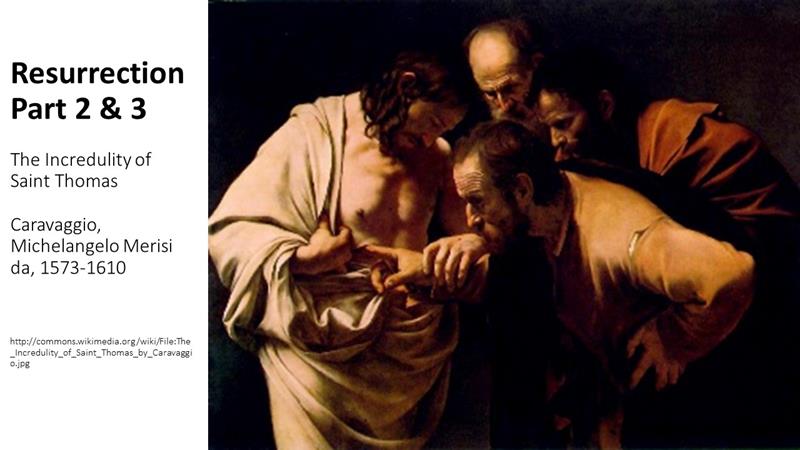

Jeff Garrison Like Thomas, I also have doubts. I was just not willing to speak up. Can this really be Jesus? After all, his body was so broken when they pulled him off the cross. Yet, he’s now in front of us. Jesus insists that Thomas, who doubted when they said Jesus had risen from the dead, stick his finger into his wound. I’m watching. Thomas is reluctant, but Jesus grabs his wrist and pulls his hand toward the wound. Can this really be the same Jesus, that just a little over a week ago, hung on a cross? And is he the same Jesus we followed throughout Galilee? Will people believe us when we tell what we’ve experienced? I no longer understand what is happening, but I know that nothing will ever be the same.

Like Thomas, I also have doubts. I was just not willing to speak up. Can this really be Jesus? After all, his body was so broken when they pulled him off the cross. Yet, he’s now in front of us. Jesus insists that Thomas, who doubted when they said Jesus had risen from the dead, stick his finger into his wound. I’m watching. Thomas is reluctant, but Jesus grabs his wrist and pulls his hand toward the wound. Can this really be the same Jesus, that just a little over a week ago, hung on a cross? And is he the same Jesus we followed throughout Galilee? Will people believe us when we tell what we’ve experienced? I no longer understand what is happening, but I know that nothing will ever be the same.

What a week it. From the Parade to the cross and now on the evening of the first day of a new week, the disciples gather in secret. The doors are locked. Everyone is exhausted. Fright and fatigue show on their faces. After three years, they only have each other. And now there’s a rumor going around, started by Mary Magdalene, that Jesus is alive. Some think it possible, but others believe it’s just idle tale?”

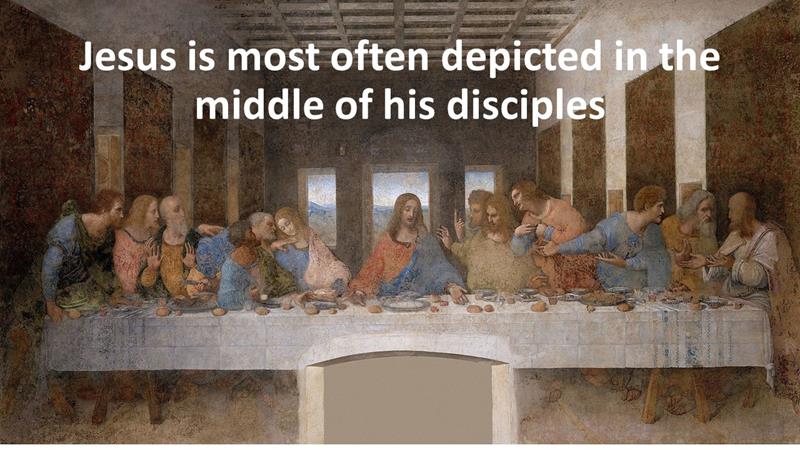

What a week it. From the Parade to the cross and now on the evening of the first day of a new week, the disciples gather in secret. The doors are locked. Everyone is exhausted. Fright and fatigue show on their faces. After three years, they only have each other. And now there’s a rumor going around, started by Mary Magdalene, that Jesus is alive. Some think it possible, but others believe it’s just idle tale?” And then suddenly, as the sun sinks in the West, Jesus appears. How did he get through the locked doors? But here he is, when he belongs, in the middle of the middle of the gathered disciples. Jesus was the one who unites the disciples. He’s always in the middle. He was even in the middle of those crucified on Friday. The middle is where Jesus belongs.

And then suddenly, as the sun sinks in the West, Jesus appears. How did he get through the locked doors? But here he is, when he belongs, in the middle of the middle of the gathered disciples. Jesus was the one who unites the disciples. He’s always in the middle. He was even in the middle of those crucified on Friday. The middle is where Jesus belongs. We could argue that this is the climax of John’s gospel. “My Lord and my God,” acknowledges that Jesus is more than the Messiah. We get a whiff of this in Matthew’s gospel where we’re told the women at the tomb worshipped Jesus.

We could argue that this is the climax of John’s gospel. “My Lord and my God,” acknowledges that Jesus is more than the Messiah. We get a whiff of this in Matthew’s gospel where we’re told the women at the tomb worshipped Jesus. What all this means to us, today, two millenniums after the resurrection? Jesus’ last words in this passage are interesting. It’s a blessing on us. “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe,” Jesus says. Did you hear that? He’s talking about you and me; he’s blessing those of us who have not had an opportunity to stick our fingers into his wounds. Instead of seeing, we believe due to the presence of the Holy Spirit and the testimony of others who have felt Jesus’ presence in their lives. And because we have faith in Jesus Christ, we’re to listen to his teachings and to live lives that strive to glorify him. That’s the challenge we have, as individuals, to listen to Jesus and to live faithful.

What all this means to us, today, two millenniums after the resurrection? Jesus’ last words in this passage are interesting. It’s a blessing on us. “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe,” Jesus says. Did you hear that? He’s talking about you and me; he’s blessing those of us who have not had an opportunity to stick our fingers into his wounds. Instead of seeing, we believe due to the presence of the Holy Spirit and the testimony of others who have felt Jesus’ presence in their lives. And because we have faith in Jesus Christ, we’re to listen to his teachings and to live lives that strive to glorify him. That’s the challenge we have, as individuals, to listen to Jesus and to live faithful. Furthermore, as a community of believers, we’re able to offer forgive sins. That’s quite a task. You know, there are a lot of good things that the church does in the community that other groups can also do, and in some cases these groups can even do it better than the church. But there is one thing that no other group can do. The government can’t do it, civic clubs can’t do it, political parties can’t do it—and that’s forgive sins. As God, Jesus has this power and he grants it to his church. For this reason, the church is an essential business. But the church isn’t a building; the church is wherever God’s people are at, which now, hopefully, is in the safety of our homes.

Furthermore, as a community of believers, we’re able to offer forgive sins. That’s quite a task. You know, there are a lot of good things that the church does in the community that other groups can also do, and in some cases these groups can even do it better than the church. But there is one thing that no other group can do. The government can’t do it, civic clubs can’t do it, political parties can’t do it—and that’s forgive sins. As God, Jesus has this power and he grants it to his church. For this reason, the church is an essential business. But the church isn’t a building; the church is wherever God’s people are at, which now, hopefully, is in the safety of our homes.

If you read the entirety of Matthew 22 (and with the extra time we may be having on hand as everything is being cancelled because of the Coronavirus, it’s not a bad idea), you’d witness a masterful campaign to trap Jesus. But Jesus isn’t so easy to catch. He’s kind of like Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign in the spring of 1862. Jackson faced much larger armies who wanted to trap and do him in.

If you read the entirety of Matthew 22 (and with the extra time we may be having on hand as everything is being cancelled because of the Coronavirus, it’s not a bad idea), you’d witness a masterful campaign to trap Jesus. But Jesus isn’t so easy to catch. He’s kind of like Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign in the spring of 1862. Jackson faced much larger armies who wanted to trap and do him in. What’s happened is that unlikely groups join together to challenge Jesus. The old cliché, “politics make strange bedfellows,” rings true. Groups who wouldn’t normally give each other the time of day have come together to take on Jesus. They sense that Jesus is challenging the existing order. You have a few Herodians, who are Jews who believe they’re be better off cooperating with the Romans. They take their name from Herod, who had Jewish blood but worked for the Empire. And you have the Pharisees; a group of seriously committed religious leaders who believe in the resurrection. Theologically, they’re most like Jesus, but Jesus constantly challenges them and exposes their hypocrisy.

What’s happened is that unlikely groups join together to challenge Jesus. The old cliché, “politics make strange bedfellows,” rings true. Groups who wouldn’t normally give each other the time of day have come together to take on Jesus. They sense that Jesus is challenging the existing order. You have a few Herodians, who are Jews who believe they’re be better off cooperating with the Romans. They take their name from Herod, who had Jewish blood but worked for the Empire. And you have the Pharisees; a group of seriously committed religious leaders who believe in the resurrection. Theologically, they’re most like Jesus, but Jesus constantly challenges them and exposes their hypocrisy. What we read this morning could be described as one movement in a tag-team wrestling match. The Herodians and the Pharisees team up on Jesus.

What we read this morning could be described as one movement in a tag-team wrestling match. The Herodians and the Pharisees team up on Jesus. So what is Jesus telling us in this passage? Do you remember those big posters that use to sit out in front of the Post Office and government buildings with Uncle Sam pointing his finger and saying: “I want you!” I believe we could easily surmise this text into a big poster of God saying: “I want you!”

So what is Jesus telling us in this passage? Do you remember those big posters that use to sit out in front of the Post Office and government buildings with Uncle Sam pointing his finger and saying: “I want you!” I believe we could easily surmise this text into a big poster of God saying: “I want you!” “Tell me,” they ask, “Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” Jesus has to be careful. Last week you heard Deanie preach about the revolutionary act of Jesus cleaning the temple. Now they want Jesus to make a revolutionary statement against the civil authorities. If Jesus says they should not pay taxes, the Herodians could have him arrested for treason. But then, if he says to pay the taxes, the Pharisees can attack him for not being a patriotic Jew.

“Tell me,” they ask, “Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” Jesus has to be careful. Last week you heard Deanie preach about the revolutionary act of Jesus cleaning the temple. Now they want Jesus to make a revolutionary statement against the civil authorities. If Jesus says they should not pay taxes, the Herodians could have him arrested for treason. But then, if he says to pay the taxes, the Pharisees can attack him for not being a patriotic Jew. Jesus asks them for a coin. Unlike us, he didn’t have to worry about where that’s coin has been or picking up some a virus from its surface. However, Jesus still has to be careful. The disciples, we know, had a common purse and he could have gone there to fetch a coin, but then the Pharisees might have charged him with toting around an engraved image of the emperor.

Jesus asks them for a coin. Unlike us, he didn’t have to worry about where that’s coin has been or picking up some a virus from its surface. However, Jesus still has to be careful. The disciples, we know, had a common purse and he could have gone there to fetch a coin, but then the Pharisees might have charged him with toting around an engraved image of the emperor. Give to God what is God’s. This phrase is often overlooked. We tend to get hung up on what is Caesar’s and what is ours. We get hung up on the petty details and we miss the important question. What does it mean for us to give ourselves to God?

Give to God what is God’s. This phrase is often overlooked. We tend to get hung up on what is Caesar’s and what is ours. We get hung up on the petty details and we miss the important question. What does it mean for us to give ourselves to God? Earlier I mentioned Stonewall Jackson, whose biography I’m currently reading. But let me tell you two other Civil War stories, they’re both short, and demonstrate this point. At the Battle of Shiloh in the spring of 1862, Albert Sidney Johnson led the Confederate troops as they overwhelmed the Union forces near Pittsburg Landing along the Tennessee River. It was a bloody day and the Union lines were broken in places. During a lull in the first day of battle, Johnson, seeing a number of wounded Union soldiers in need, ordered his surgeon to set up an aid station and to tend to their needs. According to Shelby Foote in his novel about the battle, his surgeon, Dr. Yandell protested. Johnson cut him off saying “These men were our enemies a moment ago. They are our prisoners now. Take care of them.” A few minutes later, a stray bullet struck Johnson’s leg and without medical aid, he quickly bled to death.

Earlier I mentioned Stonewall Jackson, whose biography I’m currently reading. But let me tell you two other Civil War stories, they’re both short, and demonstrate this point. At the Battle of Shiloh in the spring of 1862, Albert Sidney Johnson led the Confederate troops as they overwhelmed the Union forces near Pittsburg Landing along the Tennessee River. It was a bloody day and the Union lines were broken in places. During a lull in the first day of battle, Johnson, seeing a number of wounded Union soldiers in need, ordered his surgeon to set up an aid station and to tend to their needs. According to Shelby Foote in his novel about the battle, his surgeon, Dr. Yandell protested. Johnson cut him off saying “These men were our enemies a moment ago. They are our prisoners now. Take care of them.” A few minutes later, a stray bullet struck Johnson’s leg and without medical aid, he quickly bled to death. A second story comes from the city of Wilmington during the Civil War. In 1862, a blockade runner that had come in from the Caribbean brought Yellow Fever to the town. Those who could fled to the country, but several of the pastors and the leading citizens of the town stayed behind, feeling it was their Christian obligation to help out the victims. Over 400 people died of Yellow Fever that fall, including many of those who intentionally stayed to care for the dying.

A second story comes from the city of Wilmington during the Civil War. In 1862, a blockade runner that had come in from the Caribbean brought Yellow Fever to the town. Those who could fled to the country, but several of the pastors and the leading citizens of the town stayed behind, feeling it was their Christian obligation to help out the victims. Over 400 people died of Yellow Fever that fall, including many of those who intentionally stayed to care for the dying. Give to God what is God’s, is the message here. So yes, we should pay our income tax. And when you write that check this April, we might remember that giving Caesar his due can be a lot easier than giving to God what is his. For our whole life belongs to God. But then, God’s given us life and in Jesus Christ has redeemed us to be his people. That’s a debt we can’t repay, nor is such repayment expected. As the old hymn goes, “Jesus paid it all.”

Give to God what is God’s, is the message here. So yes, we should pay our income tax. And when you write that check this April, we might remember that giving Caesar his due can be a lot easier than giving to God what is his. For our whole life belongs to God. But then, God’s given us life and in Jesus Christ has redeemed us to be his people. That’s a debt we can’t repay, nor is such repayment expected. As the old hymn goes, “Jesus paid it all.”