This was originally posted in my other blog and written in January 2012, shortly after making this trip.

The air is crisp and Orion has dropped into the western sky as we make our way into the Flagstaff train station. The waiting room is nearly filled with passengers and baggage awaiting the eastbound arrival of the Southwest Chief. It’s 5:15 AM and we’re fifteen minutes before the train is supposed to arrive. I’ve parked the rental car in the city lot across the tracks, placed the keys in the drop box and took a seat on the old wood benches. The train is running fifteen minutes late. Outside one of Warren Buffet’s Burlington Northern Santa Fe trains of containers race through town, on its way to Los Angeles and then to a ship to where ever. A few minutes later another train approaches from the west, heading east, with containers that probably originated somewhere in Asia, most-likely China. At 5:41, the time the train was to have departed Flagstaff, but we learn it’ll be another twenty minutes before it arrives.

At six, everyone begins collecting their luggage. The station agent instructs those in coaches to head to the right and those with sleeper car accommodations to go left. We make our way to the 430 car where an attendant takes our tickets, helps us aboard and directs us to our assigned berths. “The diner opens in 20 minutes,” we’re informed. At 6:10, the engineer blows his horn, signaling that it’s time to go. A few seconds later, the train begins to move into the darkness of the Southwest. In my compartment, I stare out into the dark sky as we leave the city. I nod off for a few seconds, but it’s hard to get back to sleep, so mostly I look out the window. To the southeast the sky is just a bit lighter and fewer of the stars can be seen. Slowly a thin red line is seen on the horizon and it gradually grows into a band of red. I make out the shape of what few trees grow in this country, the utility poles and lines of fence posts. As it becomes lighter, I notice I can tell the difference between the types of brush.

A little before 7 AM, I head to the dining car for breakfast. The train pulls into Winslow, stopping only for a minute to let off and pick up passengers. I’ve been through this town several times and have yet to see “a girl in a flatbed Ford.” The waitress, a young Hispanic woman with a bright smile, brings coffee and informs us of the day’s special. I decide to have the omelet made with three eggs, spinach, onions and tomatoes with a side of grits and cinnamon raisin toast. It’s a filling breakfast and the chef liberally sprinkled oregano on the omelet, giving it a nice spicy taste. While at breakfast, the sun breaks the horizon and its rays immediately light up the desert floor. Along the interstate, silver trailers pulled by semis reflect the light. Fence posts and utility poles cast long shadows. As the sun rises, the shadows are reeled in. We pass numerous freight trains, mostly hauling containers, but there’s one with piggy back trailers, and unit train of coal cars, another with closed hoppers hauling grain and another of tankers, hauling chemicals.

Before I realize it, the train has cut through the Petrified Forest National Park and is running along the Pesrco River as it makes its way to the New Mexico border. Although Interstate 40 parallels this section of track, it was originally Route 66, the highway made famous by Steinbeck in his Depression era novel, The Grapes of Wrath. When I was in school in Pittsburgh, I met a retired dentist who told me about his family’s trip out west in 1923. The man was in his 80s at the time I knew him, but was only about ten when his dad, who was a physician, decided to take off the entire summer. He packed up the family in a large car he described as looking like something off the Beverly Hillbillies set. As this was before road trips were popular and motels and service stations dotted the landscape; the family had to provide for themselves. They mostly camped at night and cooked their own food (carrying tents and a stove). He said that from the time they left Kansas City until they arrived in Los Angeles, the only paved roads were in towns. They had to serve as their own mechanics, too, often fixing half-dozen or so flats a day. As they boiled under the hot sun of the Southwest, they complained to their dad as to why they were driving while others were zooming past their car, riding comfortably in the sleek trains along the Atkinson, Topeka and Santa Fe Route.

The train I’m on was the descendant of the Santa Fe Super Chief, which was introduced in the 1930s. At its time, the Super Chief was luxury on rail, featuring all Pullman sleeper cars powered by diesel engines. This was the train of Hollywood Stars and would later give the framework for the movie “Silver Streak,” which although it used a different name, followed the Santa Fe’s route between LA and Chicago and featured the comic antics of the young Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder.

We reach Gallup at 9 AM. From the sounds of the announcement, it sounds like the train crew is having problems with folks getting off the train to smoke and holding up operations. Gallup is just a quick stop to drop off and pick up passengers, but many have jumped onto the platform where they can legally smoke. The conductor wants to make up time and he tells people to only get off the train at scheduled stops. Since Amtrak went non-smoking twenty-some years ago, they have encouraged people who need to puff to take advantage of longer stops where they service the train. The next such stop is Albuquerque.

After Gallup, we climb. The wheels of the train squeak in the curves as they scrape against the side of the rails. To our north is a mesa that rises several hundred feet, the red Navajo sandstone is rich in the morning sun. To our south are lava fields, with the broken black rock only rising maybe fifty feet. Occasionally, in valley of sage is an ancient cottonwood, its huge trunk sprouting hundreds of scrawny limbs that twist every-which-way. This is Native American country. There are traditional southwest adobe housings along with many trailer and manufactured homes. Also, along what was once Route 66, are the ruins of motels and restaurants and trinket shops. For a hundred miles or so out of Gallup, the tracks parallel Interstate 40, alternating between being just north or south of the freeway. About fifty miles out of Albuquerque, the tracks drop to the southeast, before heading north along the upper waters of the Rio Grande. For the next three hundred miles, the tracks head north, paralleling Interstate 25.

During the morning, my daughter practices her violin and plays with the keyboard on her ipad to figure out the notes to a favorite song. I spend my time writing in a journal, looking out the window and reading Janisse Ray’s book, Drifting into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River. No one is in a hurry.

Our reservation for lunch in the dining car is at 12:30 PM. The nice thing about a sleeper is that all meals are included, which means I eat more than I should. I have a veggie burger, made out of black beans. It’s pretty good. Included are chips, ice tea and desert. I have a cup of raspberry sorbet.

We arrive in Albuquerque on-time, having made up nearly thirty minutes. Albuquerque is a long stop, nearly forty minutes, as the conductors and engineers change (the car attendants and dining car attendants remain the same the entire trip) and the train’s locomotives are fueled while the water tanks in the passenger cars are filled. During the stop here, I get out and walk up and down the tracks. On the edge of the tracks are Native American vendors selling jewelry and woven rugs and hats. We leave Albuquerque at 12:10, right on time. As we leave the city, the tracks take us through back yards that all seem to contain a wood-fired adobe beehive oven (something I’d always wanted). The houses all have satellite dishes. Some are traditional southwest looking homes, but many are not.

The Lamy station is the transfer point for those whose destination is Santa Fe. Ironically, although the famous town became the name of a railroad, the main line never made it to Santa Fe. The mountains were too steep to put the tracks into the town, so the town of Lamy was built. A short-line still branch off the mainline here, but those passengers desiring to get to Santa Fe, there is a bus. The train snakes through steep cuts in the pale orange sandstone as we leave Lamy. At times, the walls are so close to the tracks that if a window was open, one could reach out and touch the rock. Our progress is slow as the grade is steep as we move into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, climbing up the Glorieta Mesa. According to the timetable, it’ll take us nearly two hours to cover the 65 miles between Lamy and Las Vegas. The snow is also deeper, pinion and gamble oaks are now mixed in with the juniper. The late summer blooms on the rabbit brush is now brown.

Once we reach the Glorieta sidings, the track isn’t quite as steep and the train picks up speed. The westbound Southwest Chief passes us; it’ll be in LA tomorrow morning. I head to the lounge/observation car where I spend the afternoon, looking at the scenery (here I can see both sides of the tracks) while writing and talking to fellow passengers. We parallel Interstate 25; when the tracks are level we make good time and when they are steep, we slow down. Here, on top of the mesa, there are fewer cuts into the rocks and as the train snakes, we can see the engines up front and the coach cars on the back end.

Las Vegas, New Mexico isn’t as glitzy as its named counterpart in Nevada. But it’s an older town along the Santa Fe Trail. Next to the typical mission style train station Castendada, an old hotel and “Harvey House.” In the days before dining cars, the trains would stop here and the folks at the “Harvey House” were assigned the task of feeding the entire train as quickly as possible in order that they could get back on the road. Leaving Las Vegas at 3:15, the tracks carry us along high plateau, mostly grasslands with the occasional windmill and ranch house. The sun is now dropping in the southwestern sky as the magic hour approaches. In the winter, the sun seems to hang on a little longer and everything is bathed in soft light. The brown grass turns golden. Yesterday, at this time, we were driving across Southern Utah and Northern Arizona, through the polygamous towns of Hillsdale and Colorado City as we were heading to Flagstaff to catch the train. Canaan Mountain, in its various bands of colored sandstone, was beautiful in the low light. Today’s landscape isn’t quite as dramatic but it’s still beautiful as the sun casts warm hues across the plateau. The sun finally gives up and drops behind the mountains a few minutes before we arrive in Raton.

Raton is a longer stop and I get off the train and walk up and down the platform. It’s colder, now that the sun has set and we’re in higher elevation. In the summer, thousands of Boy Scouts get off here in order to visit the Philmont Scout Ranch, for a week or two of hiking in the Desert Mountains of the Southwest. I’m told that having a large scout group on the train can be a trying experience for the rest of the travelers, but we don’t have to worry about it as its winter. I’ve taken this route once before, during the summer of 1993, but since I had a sleeper, I was spared the experience as the scouts onboard were all in coach. When we leave Raton, we’re on some of the steepest track in the country. We’re five cars behind the locomotives, yet can hear them groan as they work hard to pull us up the grade. At times it seems we’re going no faster than I can walk. The track is so steep that a marble dropped on the floor would race to the back of the car. It takes nearly an hour to go from Raton, New Mexico to Trinidad, Colorado, a distance of only 24 miles. At the summit, the tracks are at 7588 feet, the highest point along the Santa Fe line. We rush through the Raton Tunnel and then begin our descent. But even the downhill is steep and curvy and the engineer maintains a slow descent. Its pitch dark by the time we reach Trinidad.

Our dinner reservations are at 6 PM and since we don’t have enough for a full table, we are seated with a solo traveler who introduces himself as “Dave, a hillbilly from West Virginia.” He’s quite a talker, telling about working in the coal mines as a kid and then leaving the state and doing various jobs around the country including working behind the scenes in the movies. He’d gotten on in Santa Fe and is heading back to his home country where he’s planning on retiring. For dinner, I have a chipotle beef tip with apricot sauce, roasted vegetables, rice and a salad. I’m not a big beef person, unless the meat has been spiced up some. This was delicious! After dinner, the train stopped in La Junita, Colorado. We’re fifteen minutes early. Since the engineers and conductors change here; we have nearly a 30 minute break. But it’s cold, 14 degrees, so after walking the length of the train a few times, I seek the shelter of the car, where our attendant is busy putting down the beds. I’d talked to him earlier today. He’s been an attendant for Amtrak for 35 years. He started working with them during the summer, when he was a grad student working on a photojournalism degree. He stayed with it, taking on average three six-day trips a month (a trip from LA to Chicago with a layover day and then back to LA is considered a 6 day trip).

Through this section, I have a good data signal and spend the next hour updating my facebook page and reading and commenting on blogs. We stop briefly in Lamar, to let off and receive passengers. As we leave, I put away my laptop and pull the covers over me. Outside, it’s cold and snowy. The stars are bright and Orion and his dog seem to be just outside my window. We pass a number of grain elevators and enter the Central Time Zone. It’s now 10:30 PM and I call it a night.

I sleep well, waking up only once, at 5:15 AM. We’re at Topeka, then. The station is on the other side of the train, and from my window I look out at a rather sizable rail yard. Freight trains are being assembled. The lights are so much that I can barely see the stars, but I pick out what I think are the two bright stars that make up the arrow in the archer’s bow, but then realize I shouldn’t be seeing that constellation this time of the year and that it must be Cygnus the Swan. As we begin to move out, I fall back asleep. At 7 AM, the announcer comes on and says we’re in Kansas City, a fifteen minute stop. I pull on a gym suit and walk outside for fresh air. When the engine whistles and the conductor calls “all aboard,” I jump back onboard and go to the diner for breakfast. This morning I take it easy, enjoying a bowl of steel cut oatmeal along with some fruit and toast and, of course, coffee. We’re seated with a woman from Royal Oak, Michigan, who has been visiting family in Kansas. She’ll be on the same train we’ll take out of Chicago, although she’ll have two and a half more hours of travel, arriving at her station at midnight (if the train is on time). As we eat, we cross the Missouri River. A unit train of grain hoppers passes us, heading west. There is no snow here in the Midwest, just brown fields and bare trees. The tracks cut through the northwest corner of Missouri and the southeast corner of Iowa, as we race along through farmland and wooded areas and the occasional town. Broom sledge, brown and dry, line the tracks thought much of this section. We stop in La Plata, Missouri. This is a small station and we have to make two stops, one to let off the sleeping car passengers and again to let off those riding in the coaches on the back end of the train. Over half of the passengers appear to be Amish in their traditional dress.

As we approach Fort Madison, Iowa, along the Mississippi River, we pass the factory where they make the large electrical windmills. Hundreds of blades are stored around the buildings and some of them are on secured to flat rail cars, awaiting shipment. Fort Madison is a “smoke stop” and I get off to get some fresh air (there seems to be only one smoker in our car and he walks far away from the train to light up). I walk around a bit, but we are only stopped for a few minutes before the engineer blows the whistle and the “all aboard” call is made. It’s okay because they have already called the 11:45 AM dining reservations (it’s only 11:15). We’re about 10 minutes behind schedule, but all bets are on that we’ll make that back up as we race into Chicago. In the dining car, as we pull out of the station, the tracks parallel the Mississippi River. A paddle-wheeled riverboat is tied up at the docks and I pose to get a shot when we go by, but just before we get there a pair of orange, black and yellow Burlington Northern Santa Fe locomotives on the next track blocks my view. It’s a unit of cars filled with automobiles. Soon, the tracks make a right hand bend and we’re on the trestle over the Mississippi and into Illinois, the final state of our journey. This is farm country. The dirt is black and the fields of corn and soybeans are fallow in the winter. Along the edges of the fields are farm houses and barns.

For lunch, I have the chef’s special. I am not normally a big macaroni and cheese fan, but his mac and cheese includes cauliflower, corn, garlic and chipotle sauce. It was good and has a spicy bite to it. The meal is especially filling since it includes a salad and a dinner roll. When we leave, we say goodbye to the dining staff as they’ve treated us well this trip.

Our first stop in Illinois is Galesburg, a railroad town. Tracks merge here before heading into Chicago. At the station, many of the Amish get off the train along with a few other passengers. Next to the station is the Galesburg Rail Museum. Someday I need to make a stop here. On display is a Burlington Route steamer with a couple of Pullman cars. There have been a number of old steam locomotives on display in the various towns we’ve traveled through. In this part, they’re always the over-sized Burlington Route or CB&Q (Chicago, Burlington and Quincy) steamers designed for fast transportation across the plains. On the other side of Kansas City, they’re Atkinson, Topeka & Santa Fe locomotives, most of which are smaller and better on the curves. Riding through this country of farms and small cities, we see the backyard of America, filled with clothes lines and swing sets. Many of the streets that run out from the tracks have wooden two-storied box-shaped homes and are lined with trees. But it doesn’t quite look right as there is no snow on the ground, which is usual for January.

We pull into Chicago’s Union Station on time, at 3 PM. We’ve covered 1699 miles in 33 hours, having traveled through deserts and mountain, through reservations and many small towns and a few larger cities, crossed the great rivers and the rich farmland of America’s heartland!

With a three hour layover, we head to the Great Room. It’s still decorated for Christmas. We camp out on the wooden bench seats. As I finish reading Ray’s book, Drifting into Darien, a police officer stops to ask what I’m reading. I try to explain the book and he asks if it’s like the book they made into a movie with Brad Pitts about two boys and their father a Lutheran minister in Montana. “You mean, A River Runs Through It?” I ask. “That’s it,” he says. I correct him saying that the dad wasn’t Lutheran but Presbyterian and explain the differences between the books. Although I am enjoying Ray’s writing, it’s nothing like MacLean’s masterpiece. I tell him a bit about Ray and her writing about nature in the South. He acknowledges the number of great southern writers and notes the rising number of southern crime fiction authors. I admit I haven’t read much in that genre unless Carl Haaisen’s writing could be classified in the genre. I’m surprised that he knows Haaisen, and he asks if I’ve read Thomas Cook. I haven’t and he tells me about a crime fiction book Cook wrote that’s sent in Birmingham, during the days of Bull O’Conner. As we talk, he seems to know a lot about Cook and the setting and I ask if he knows Cook and he admits that he’s talked to him a number of times, saying that he plays in the crime fiction genre. When I ask if he’s published anything, he acknowledges that he’s shopping a novel, but has a non-fiction book in print titled Just the Facts: True Tales of Cops and Criminals.

At five, an hour before departure, we head into the crowded waiting room. I talk a bit with an Amish man who’s just travelled here from central Pennsylvania to see a couple families off to Mexico. At 5:30, the make the first call for the Wolverine, the train that’ll take us to Kalamazoo and home. We board, climbing up iced-over stairs. The train is crowded. We start slowly, going through the maze of tracks south of Chicago, before circling around the south shore of Lake Michigan. It’s a short trip, just two and a half hours (plus another hour due to the change of time zones). At Niles, I call my friends where I’d left my truck. They tell me they’ll be there at the station. It’ll be nice to be home as I hear it’s been snowing. At 9:30, right on time, the train stops in Kalamazoo and we carefully make our way down the icy steps. After a thirty minute drive, our trip will be over.

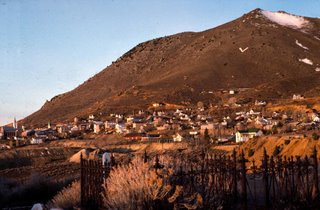

People turn to the church when there is a death because we can offer hope for something beyond our frail mortal bodies. In all the work I did on the history of Western Mining Camps, one of the surprising things I learned was how at the time of death, even people who religiously avoided the shadow of the steeple, would be brought back for a funeral. The friends of Julia Bulette, Virginia City’s most famous prostitute, sought out the Presbyterian minister for her funeral. Mark Twain in Roughing It has a wonderful tale about Buck Fanshaw’s funeral. Fanshaw, a leader of the “bottom-stratum of society” and based on a real-life character who had a relationship with Bulette, died. The local roughs elected Scotty Briggs to “fetch a parson” to “waltz Fanshaw into handsome” (their word for heaven). The dialogue between the minister and Scotty is classic Twain.

People turn to the church when there is a death because we can offer hope for something beyond our frail mortal bodies. In all the work I did on the history of Western Mining Camps, one of the surprising things I learned was how at the time of death, even people who religiously avoided the shadow of the steeple, would be brought back for a funeral. The friends of Julia Bulette, Virginia City’s most famous prostitute, sought out the Presbyterian minister for her funeral. Mark Twain in Roughing It has a wonderful tale about Buck Fanshaw’s funeral. Fanshaw, a leader of the “bottom-stratum of society” and based on a real-life character who had a relationship with Bulette, died. The local roughs elected Scotty Briggs to “fetch a parson” to “waltz Fanshaw into handsome” (their word for heaven). The dialogue between the minister and Scotty is classic Twain.

At death and in times of peril, the church is a symbol of our faith and the hope we have for something we can never fully comprehend in this life, the resurrection.

At death and in times of peril, the church is a symbol of our faith and the hope we have for something we can never fully comprehend in this life, the resurrection.

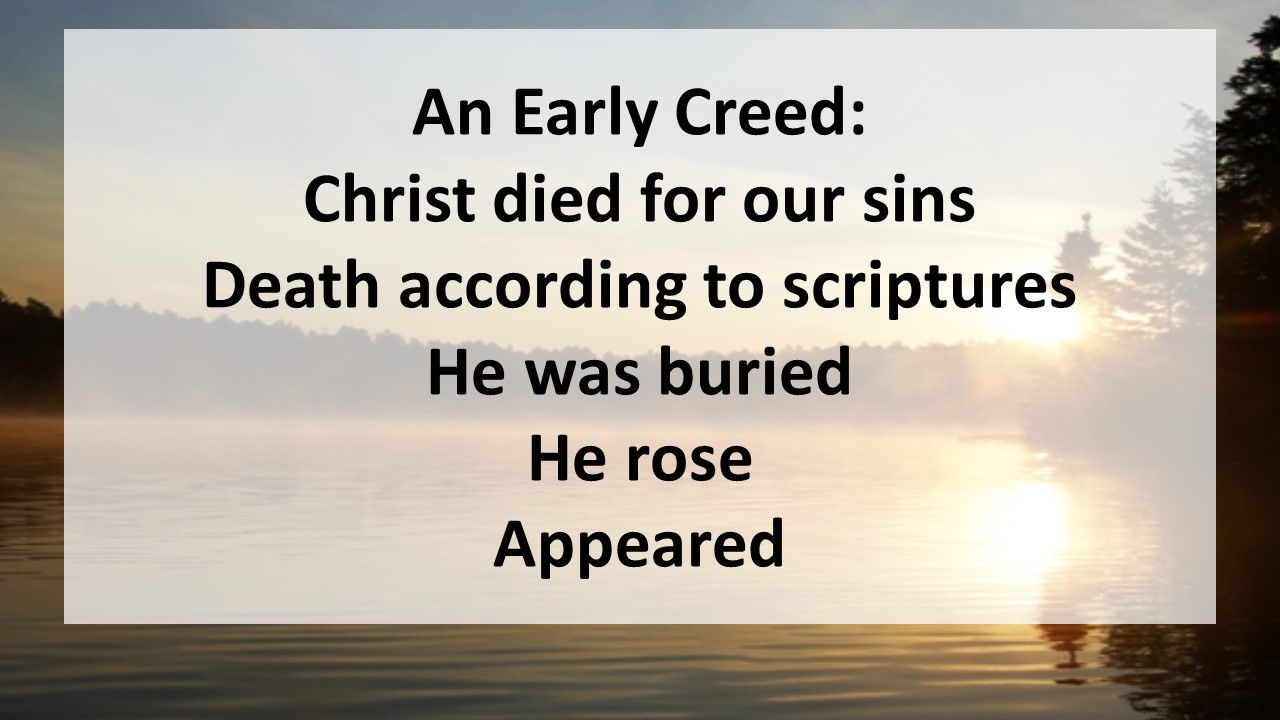

However, there is good news. Although death came through a human being, so too has the resurrection come through a human being. Paul lifts the Christmas doctrine of the incarnation. In Jesus Christ, God became flesh! Christ is the first-fruit of the resurrection, a term that probably meant more to Paul’s audience than to us today. For you see, the Jews were to bring the first of the harvest, their first-fruits, to God as an offering of thanksgiving. We tend to give God what is left, not our first-fruit, which probably says a lot more about our spiritual state that we’d honestly like to admit. However, this isn’t about our giving, it’s about God’s gift, for God the Father gave us his first-fruit, in that of his Son.

However, there is good news. Although death came through a human being, so too has the resurrection come through a human being. Paul lifts the Christmas doctrine of the incarnation. In Jesus Christ, God became flesh! Christ is the first-fruit of the resurrection, a term that probably meant more to Paul’s audience than to us today. For you see, the Jews were to bring the first of the harvest, their first-fruits, to God as an offering of thanksgiving. We tend to give God what is left, not our first-fruit, which probably says a lot more about our spiritual state that we’d honestly like to admit. However, this isn’t about our giving, it’s about God’s gift, for God the Father gave us his first-fruit, in that of his Son. All this is a part of God’s plan in history, Paul notes. It’s all a part of the great plan to destroy all authorities and powers that defy or challenge God. At the end, there will be nothing to draw our attention from the Almighty. All idols will be destroyed, all that which we fear will be removed, the last of which is death itself. With the removal of that great enemy which has haunted the human race since the beginning, we can worship God without fear or distraction.

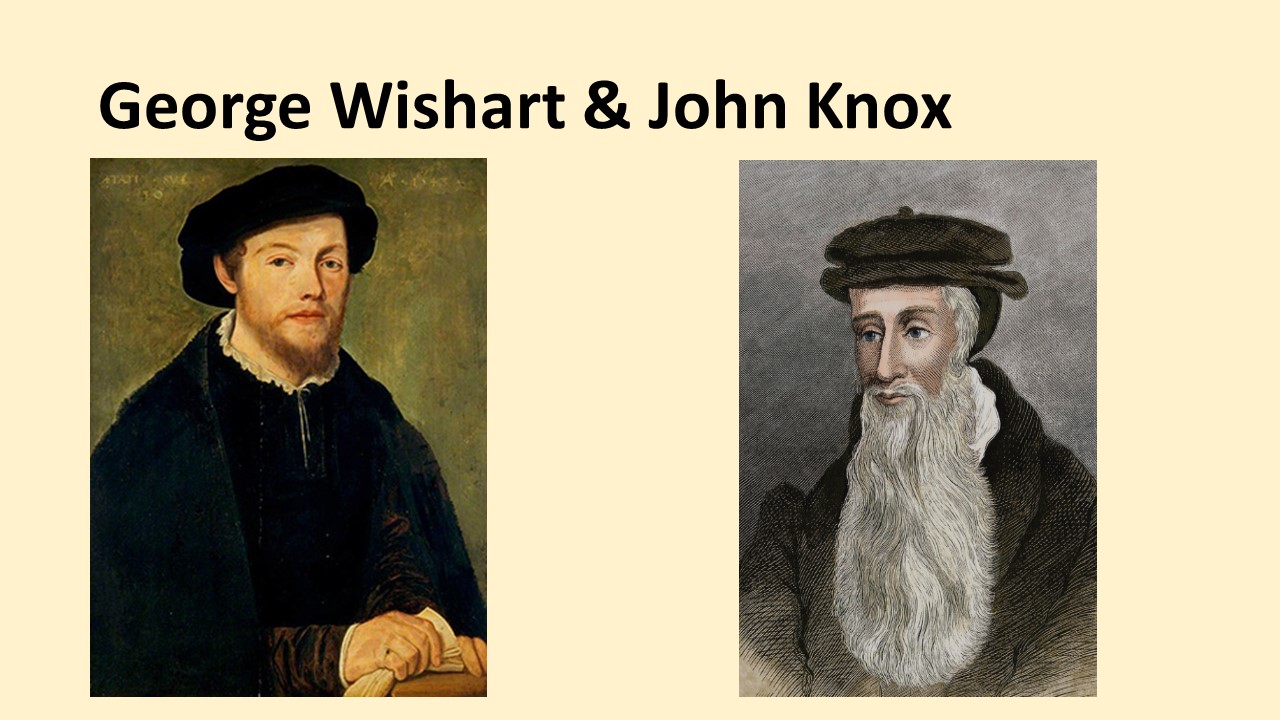

All this is a part of God’s plan in history, Paul notes. It’s all a part of the great plan to destroy all authorities and powers that defy or challenge God. At the end, there will be nothing to draw our attention from the Almighty. All idols will be destroyed, all that which we fear will be removed, the last of which is death itself. With the removal of that great enemy which has haunted the human race since the beginning, we can worship God without fear or distraction. Kenneth Bailey, in his commentary on First Corinthians, goes into detail about the meaning of Jesus placing all his enemies (the last one being death), under his feet. Bailey suggests that verses 24-27 could be removed and the reader wouldn’t notice. You can try this yourself, at home, just leave the verses out and see how it reads. So why did Paul insert this little segue? It’s to make a political point: Jesus is Lord! If Jesus is Lord, that means Caesar isn’t Lord. He cites examples from the ancient world in which the ruler’s footstool often had engravings representing the kingdom’s enemies and when the ruler placed his foot upon the stool, he was making a statement about his power. When Christ has finished, there will be no possibilities of his enemies, including death, making a comeback!

Kenneth Bailey, in his commentary on First Corinthians, goes into detail about the meaning of Jesus placing all his enemies (the last one being death), under his feet. Bailey suggests that verses 24-27 could be removed and the reader wouldn’t notice. You can try this yourself, at home, just leave the verses out and see how it reads. So why did Paul insert this little segue? It’s to make a political point: Jesus is Lord! If Jesus is Lord, that means Caesar isn’t Lord. He cites examples from the ancient world in which the ruler’s footstool often had engravings representing the kingdom’s enemies and when the ruler placed his foot upon the stool, he was making a statement about his power. When Christ has finished, there will be no possibilities of his enemies, including death, making a comeback! In the winter of 2000, I had the opportunity to spend a few weeks in Korea: preaching, sightseeing and mountain climbing. I visited the imperial city in Seoul, where the emperor once ruled, his throne built on a hill that allowed him to overlook the city. In 1910, Japan invaded Korea. The Japanese decided it was too dangerous to destroy the ancient throne, so instead they built a modern government building to block the view from the city. I learned there had been a great controversy over what to do with this building that was architecturally significant. Many wanted to tear it down, which is what happened, but others wanted to relocate it. One of the more creative ideas, which caused a minor international incident with the Japanese, was to dig a hole and sink the building and then glass over the top. That way, the building would not be destroyed, but the Korean people could have the satisfaction of “walking over” or stomping on the visible representation of 40 years of Japanese occupation.

In the winter of 2000, I had the opportunity to spend a few weeks in Korea: preaching, sightseeing and mountain climbing. I visited the imperial city in Seoul, where the emperor once ruled, his throne built on a hill that allowed him to overlook the city. In 1910, Japan invaded Korea. The Japanese decided it was too dangerous to destroy the ancient throne, so instead they built a modern government building to block the view from the city. I learned there had been a great controversy over what to do with this building that was architecturally significant. Many wanted to tear it down, which is what happened, but others wanted to relocate it. One of the more creative ideas, which caused a minor international incident with the Japanese, was to dig a hole and sink the building and then glass over the top. That way, the building would not be destroyed, but the Korean people could have the satisfaction of “walking over” or stomping on the visible representation of 40 years of Japanese occupation.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

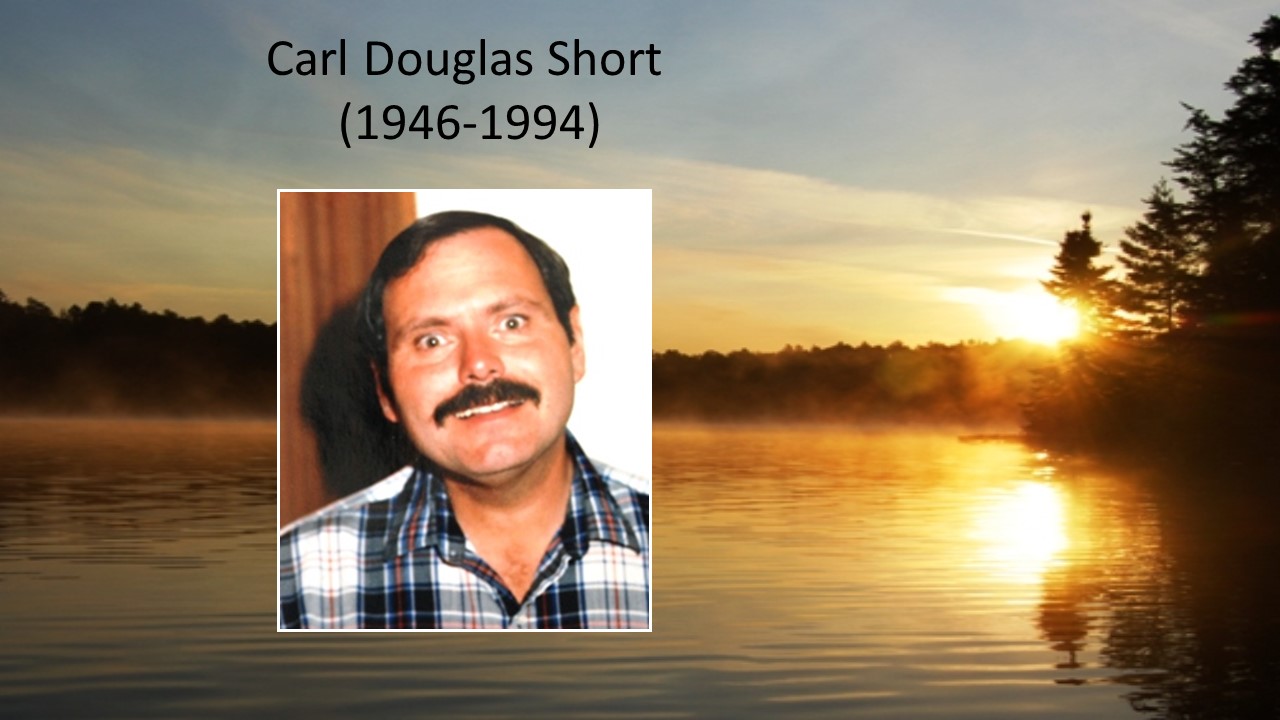

His name was Carl Douglas and he had lived in Virginia City when I was a student pastor there. In the five or so years in between, I’d lost track of Doug, but I had been with him when the doctor had given him the bad news that he had cancer. When I last talked to him, it was in remission, but had come back with a vengeance. I’d been praying for this friend, without knowing it, for months. And now I was sitting across from his estranged sister. Unlike her, I had only good memories of her brother. New Year’s Eve 1988 was one. It was a Saturday and we both had plans for the evening, but when I was in the church practicing my sermon I heard water running and after checking found there was a busted pipe in the heating system, underneath the organ. Doug came right down and we spent a couple of hours fixing the pipe so that we might have heat for Sunday. That was only one example. He was known of his kindness, for being quick to offer a hand to those in need.

His name was Carl Douglas and he had lived in Virginia City when I was a student pastor there. In the five or so years in between, I’d lost track of Doug, but I had been with him when the doctor had given him the bad news that he had cancer. When I last talked to him, it was in remission, but had come back with a vengeance. I’d been praying for this friend, without knowing it, for months. And now I was sitting across from his estranged sister. Unlike her, I had only good memories of her brother. New Year’s Eve 1988 was one. It was a Saturday and we both had plans for the evening, but when I was in the church practicing my sermon I heard water running and after checking found there was a busted pipe in the heating system, underneath the organ. Doug came right down and we spent a couple of hours fixing the pipe so that we might have heat for Sunday. That was only one example. He was known of his kindness, for being quick to offer a hand to those in need. few months after the funeral, Elvira arranged to move back to Nebraska. When I think about all this, I’m amazed. I see God’s hand at work. What was the probability Elvira would end up in a church in a distant city where the pastor knew her son? There was actually a good chance her son could have died and she’d never seen him or even been able to attend the funeral, or even know of his death. Thankfully, she was able to see him and attend his funeral. God enjoys working to bring about surprises and joy!

few months after the funeral, Elvira arranged to move back to Nebraska. When I think about all this, I’m amazed. I see God’s hand at work. What was the probability Elvira would end up in a church in a distant city where the pastor knew her son? There was actually a good chance her son could have died and she’d never seen him or even been able to attend the funeral, or even know of his death. Thankfully, she was able to see him and attend his funeral. God enjoys working to bring about surprises and joy!

N. T. Wright, an insightful theologian from the British Anglican community says this:

N. T. Wright, an insightful theologian from the British Anglican community says this: In other words, because of the resurrection, we’re now invited to live as God intends as we join God in his work of transforming the world—a transformation that begins with the open tomb on Easter morning. Everything will be changed. Jesus has defeated death and inaugurates the reclamation of the earth for God’s purpose.

In other words, because of the resurrection, we’re now invited to live as God intends as we join God in his work of transforming the world—a transformation that begins with the open tomb on Easter morning. Everything will be changed. Jesus has defeated death and inaugurates the reclamation of the earth for God’s purpose. Will we believe? Will we allow ourselves to be transformed? God is working miracles in this world. I shared one such miracle at the beginning of the sermon. God wants to reconcile the world, not just to himself, but between mother and son, brothers and sisters, friends and enemies. Will we accept God’s invitation to proclaim the good news? Will we accept the invitation to hop up on the bandwagon and follow Jesus, out of the grave and into life? Let us pray:

Will we believe? Will we allow ourselves to be transformed? God is working miracles in this world. I shared one such miracle at the beginning of the sermon. God wants to reconcile the world, not just to himself, but between mother and son, brothers and sisters, friends and enemies. Will we accept God’s invitation to proclaim the good news? Will we accept the invitation to hop up on the bandwagon and follow Jesus, out of the grave and into life? Let us pray:

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison  Do you think the Pharisees might have been picking on Jesus for the wrong reason? They get all over him for harvesting grain on the Sabbath, but don’t say anything about the fact Jesus and his disciples are in someone else’s grain field? Think about this for a moment as I go off on a tangent.

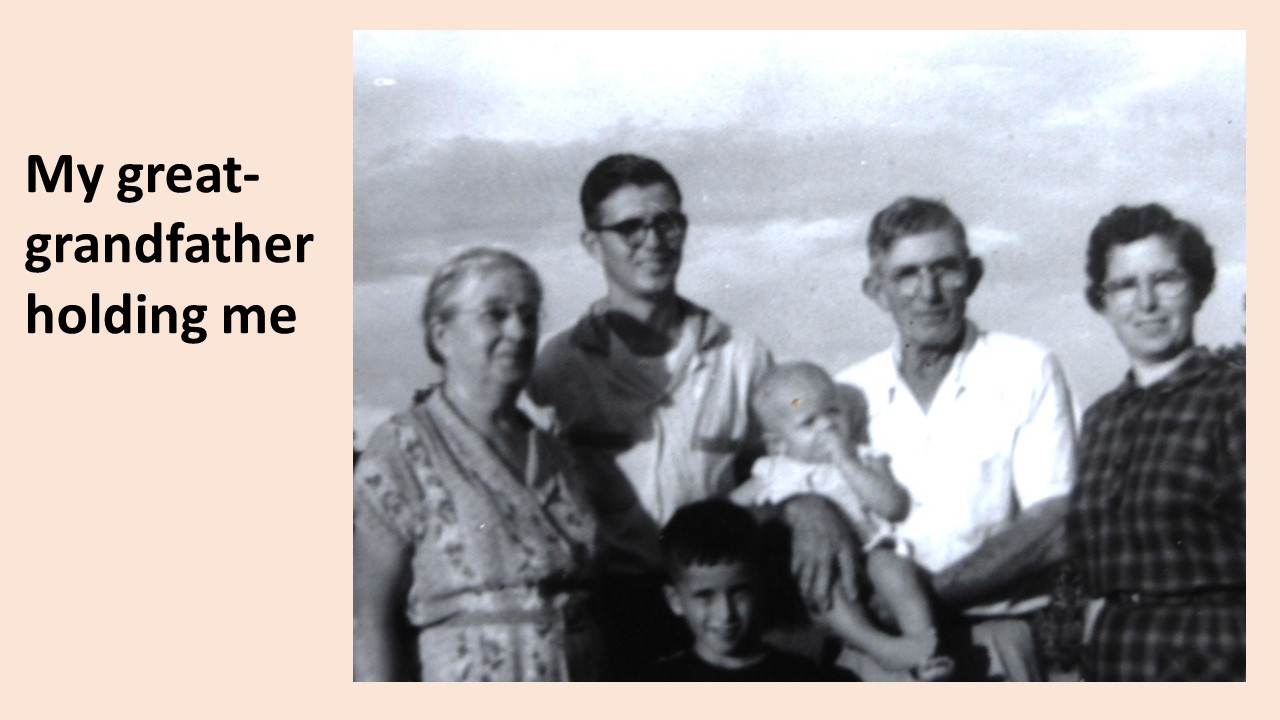

Do you think the Pharisees might have been picking on Jesus for the wrong reason? They get all over him for harvesting grain on the Sabbath, but don’t say anything about the fact Jesus and his disciples are in someone else’s grain field? Think about this for a moment as I go off on a tangent. I inherited my Presbyterianism from my great-granddaddy McKenzie. He was a strong church leader who served as an elder at Culdee Presbyterian Church for over 40 years. It was the church his father and grandfather help establish in those dark days following the War Between the States. Like most churches in the day, it emphasized the fear of God and the preacher regularly reminded the congregation about God’s judgment.

I inherited my Presbyterianism from my great-granddaddy McKenzie. He was a strong church leader who served as an elder at Culdee Presbyterian Church for over 40 years. It was the church his father and grandfather help establish in those dark days following the War Between the States. Like most churches in the day, it emphasized the fear of God and the preacher regularly reminded the congregation about God’s judgment. This brings me back to the subject of Jesus and the disciples munching in some farmer’s field on the Sabbath. The reason the Pharisees didn’t get on Jesus for his disciples harvesting food that didn’t belong to them was that Jewish law allowed one to pluck grain with their hands from their neighbor’s field. According to Deuteronomy, we’re told:

This brings me back to the subject of Jesus and the disciples munching in some farmer’s field on the Sabbath. The reason the Pharisees didn’t get on Jesus for his disciples harvesting food that didn’t belong to them was that Jewish law allowed one to pluck grain with their hands from their neighbor’s field. According to Deuteronomy, we’re told: Jesus is doing something knew. Our passage begins with an illustration about patching coats and wineskins. This is probably not something any of us have experienced for we either replace our coats or take them to the tailor on Montgomery Cross. And our wine is aged in barrels and tends to come to us in bottles. But back in the first century, you had to patch your coats, and skins were used to hold wine. So you made sure the cloth you used to patch something was preshrunk and that your wineskins were new so that it would stretch and not bust open during the fermenting process.

Jesus is doing something knew. Our passage begins with an illustration about patching coats and wineskins. This is probably not something any of us have experienced for we either replace our coats or take them to the tailor on Montgomery Cross. And our wine is aged in barrels and tends to come to us in bottles. But back in the first century, you had to patch your coats, and skins were used to hold wine. So you made sure the cloth you used to patch something was preshrunk and that your wineskins were new so that it would stretch and not bust open during the fermenting process. As the Sabbath is made for us, we should consider how it was understood in the early church. Paul tells the Romans that some think one day is better than another while others think all days are equal, and in Colossians he says we shouldn’t let ourselves be judged over the Sabbath.

As the Sabbath is made for us, we should consider how it was understood in the early church. Paul tells the Romans that some think one day is better than another while others think all days are equal, and in Colossians he says we shouldn’t let ourselves be judged over the Sabbath. The Sabbath Command is a reminder that we are not able to run ragged 24/7. We need rest, both daily (which is why night was created), and for an extended period at least once a week. The Sabbath is a day we can put our employment concerns aside, and just enjoy the creation God has given us. It’s a day we can enjoy the families that God has given us. It’s a day we can catch our breath and look around and give thanks.

The Sabbath Command is a reminder that we are not able to run ragged 24/7. We need rest, both daily (which is why night was created), and for an extended period at least once a week. The Sabbath is a day we can put our employment concerns aside, and just enjoy the creation God has given us. It’s a day we can enjoy the families that God has given us. It’s a day we can catch our breath and look around and give thanks. When I was a small child we lived on a parcel next to my great-grandparents farm. On occasion, we ate Sunday dinner with them. First thing my great-grandma did when she got home from church was make biscuits. Much of the dinner was already prepared but the biscuits had to be fresh. First, she’d take some kindling and light a fire in her wood burning stove. Don’t get the idea that we were hillbillies because my great-grandma had a perfectly good gas range sitting in her kitchen, it’s just that she preferred the wood burning stove for most of her cooking. After her death in the summer of ’64, the wood burning range was taken out, but before then I have good memories, as a five or six year old, gathering up chucks of stove wood my great-granddaddy had split. As the oven heated up, my great-grandma mixed up some flour, salt, and baking soda, cut in some lard, then added buttermilk. She’d knead the gluey glob till it was smooth, rolled it out, and cut out the biscuits. Soon a heavenly scent filled the room.

When I was a small child we lived on a parcel next to my great-grandparents farm. On occasion, we ate Sunday dinner with them. First thing my great-grandma did when she got home from church was make biscuits. Much of the dinner was already prepared but the biscuits had to be fresh. First, she’d take some kindling and light a fire in her wood burning stove. Don’t get the idea that we were hillbillies because my great-grandma had a perfectly good gas range sitting in her kitchen, it’s just that she preferred the wood burning stove for most of her cooking. After her death in the summer of ’64, the wood burning range was taken out, but before then I have good memories, as a five or six year old, gathering up chucks of stove wood my great-granddaddy had split. As the oven heated up, my great-grandma mixed up some flour, salt, and baking soda, cut in some lard, then added buttermilk. She’d knead the gluey glob till it was smooth, rolled it out, and cut out the biscuits. Soon a heavenly scent filled the room. When the meal was over, if it was meal without pie, my great-granddaddy would get up and go to the pantry and come back with a jar of molasses or honey. He’d drop a big plop of butter in his plate, pour on the sweetener, and mix it up real good with his folk. Then, throwing away all manners, he’d sop it up with the left-over biscuits. It was good. Afterwards, we kids would run out and play while the adults retired to either the back porch or, if in winter, the parlor. When we’d come back in an hour or so later, they’d all be napping.

When the meal was over, if it was meal without pie, my great-granddaddy would get up and go to the pantry and come back with a jar of molasses or honey. He’d drop a big plop of butter in his plate, pour on the sweetener, and mix it up real good with his folk. Then, throwing away all manners, he’d sop it up with the left-over biscuits. It was good. Afterwards, we kids would run out and play while the adults retired to either the back porch or, if in winter, the parlor. When we’d come back in an hour or so later, they’d all be napping. Jesus in this story doesn’t negate the Sabbath. He just encourages us to use it as it was created, for our benefit. Take a deep breath. Receive the Sabbath as a gift from a gracious God. Amen.

Jesus in this story doesn’t negate the Sabbath. He just encourages us to use it as it was created, for our benefit. Take a deep breath. Receive the Sabbath as a gift from a gracious God. Amen. Arthur C. Brooks, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America for the Culture of Contempt (HarperCollins, 2019), 243 pages, index and notes.

Arthur C. Brooks, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America for the Culture of Contempt (HarperCollins, 2019), 243 pages, index and notes.

Our Lenten series encourages us to slow down, take a deep breath, and reconnect to an unhurried God. How might this passage encourage us to make such connections?

Our Lenten series encourages us to slow down, take a deep breath, and reconnect to an unhurried God. How might this passage encourage us to make such connections?

This list reminds us that, like the seasons, there is a cycle to our lives. If Solomon had lived by the ocean, he might have added the tides. The cycles of life are all around us, but some are experienced more frequently than others. If we accept God’s sovereignty, there is no need for us to constantly be distraught over life’s ebbing and waning. We are freed to enjoy what we can while trusting and having faith that things won’t always be bad.

This list reminds us that, like the seasons, there is a cycle to our lives. If Solomon had lived by the ocean, he might have added the tides. The cycles of life are all around us, but some are experienced more frequently than others. If we accept God’s sovereignty, there is no need for us to constantly be distraught over life’s ebbing and waning. We are freed to enjoy what we can while trusting and having faith that things won’t always be bad.

In his acknowledgements at the beginning of his book on aging which I read this past week, Parker Palmer, a spiritual author from the Quaker tradition, writes:

In his acknowledgements at the beginning of his book on aging which I read this past week, Parker Palmer, a spiritual author from the Quaker tradition, writes:

We can’t control when the cycles of life happen, but we can control how we respond to them. Receive them as a gift, as grace. Amen.

We can’t control when the cycles of life happen, but we can control how we respond to them. Receive them as a gift, as grace. Amen.