While I only completed two books in May (compared to five in April), I am posting three reviews. I finally set out to complete Taylor Branch’s trilogy about the Civil Rights movement in America. I have one more volume to go!

Jim Shea, Get Up and Ride: A Humorous True Story of Two Friends Cycling the Great Allegheny Passage and C&O Canal

(2020), 189 pages with some maps and photos.

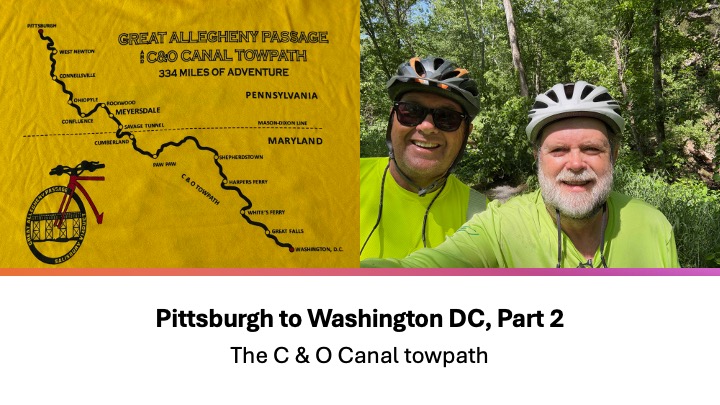

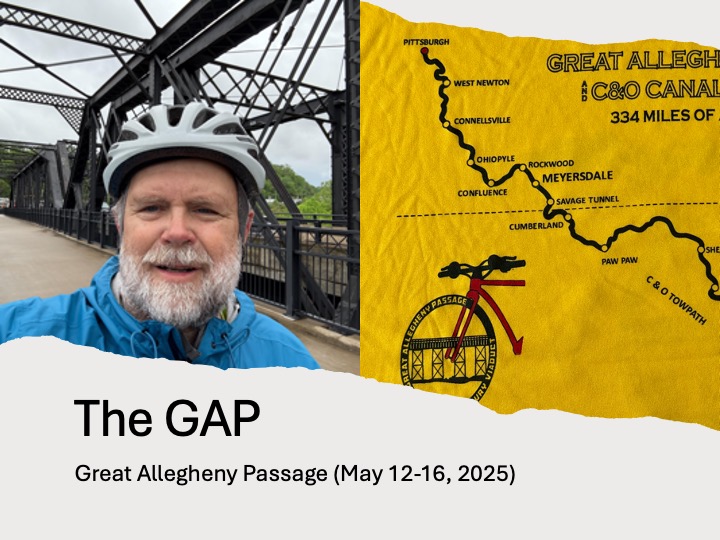

Somehow Facebook knows my brother and I are planning to peddle from Pittsburgh to Washington, D. C. in late May. I learned of this book in which two brothers-in-law did the same trip in 2010 from a Facebook advertisement.

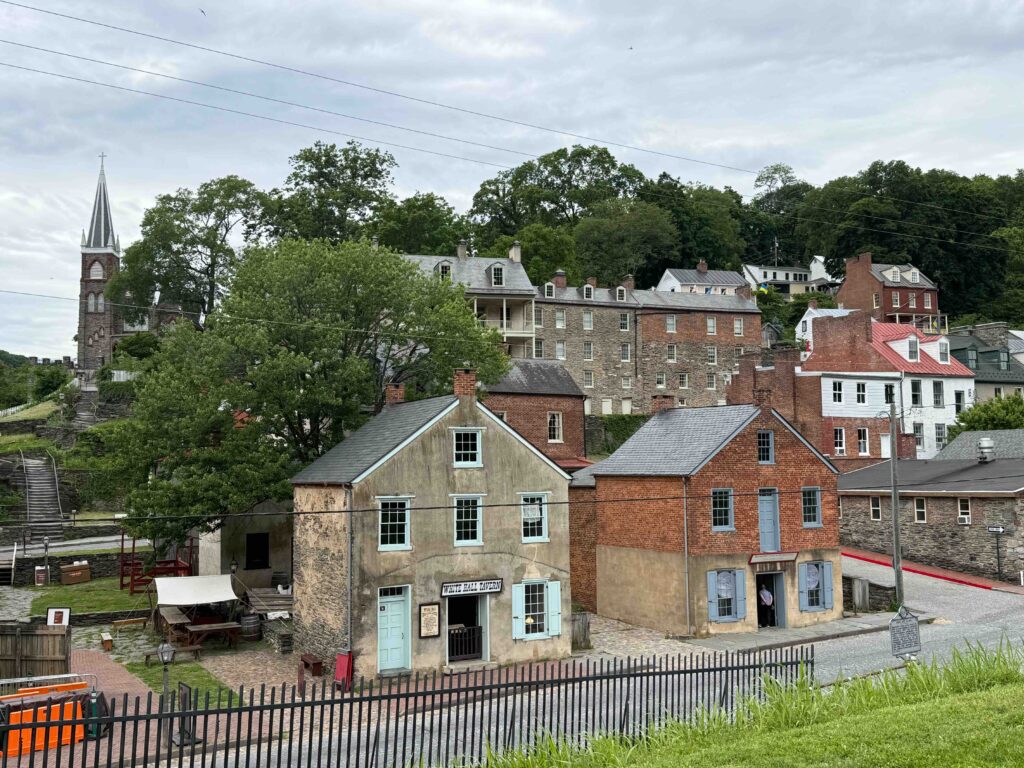

Two brothers-in-law. One teaches and has his summers off. The other finds himself between jobs. They decided to do the trip they’d been talking about for a few years. This book is easy to read and humorous, although much of the humor reminded me of listening in at a restaurant to conversation of a family unknown to me. This is not Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods or the writings of J. Marteen Troost traveling in the South Seas. But I did laugh and their stories helped me envision my own planned trips. I just hope the weather is as good for us as it was for them. (It wasn’t as I showed in my blog: Part 1 and Part 2). I can handle one day of rain, but it would be a bummer to have a week of rain!

Most of the humor of the book come from the experiences of Jim and Marty before they set off to peddle to Washington. We learn about how they often vacation together (after all, their wives are sisters). While one is from Pittsburgh (and still lives in the Steel City), the other is from just outside Washington but now (or at the time of their trip), also lives in the Pittsburgh area. One is an avid bicyclist, and the other is kind of along for the ride. While there are a few humorous things which happened during their ride, most of the laughs come from how they relate within the two families.

The author of the book speaks of not reading much as if that means he won’t sound like a Hemingway or Steinbeck. At least he can make light of himself, but I would suggest that he read more and learn about how humor works. Bill Bryson’s short adventures on the Appalachian Trail, A Walk in the Woods, which he turned into an international best seller might be a good place to start.

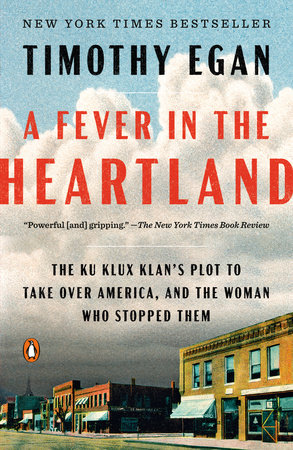

Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-65

(New York, Simon & Schuster, 1998), 746 pages including index, notes, and one set of black and white photographs.

This is the second volume of Taylor Branch’s massive undertaking of chronicling the Civil Rights Movement during the life of Martin Luther King, Jr. Unlike the first volume (review below), this is less of a biography of King than recapping what happened in these three pivotal years to the Civil Rights movement. This included the Burmingham Church Bombings, the death of voter registration workers in Mississippi, and significant Civil Rights work in Mississippi, St. Augustine (Florida), and Selma Alabama. In the background there is the death of John Kennedy and America’s deepening involvement in Vietnam.

In a way, reading this book is like reading the newspapers for three years. At times, it seems Branch jumps around, but the movement was in such flux with events happening in multiple places at the same time.

The book also takes us inside both political parties in 1964, as they struggled with what to do with the Civil Rights movement. The Democratic candidate, Lyndon Johnson, had just passed the 1964 Civil Rights act, shifting African Americans further away from the party of Lincoln, who’d freed the slaves. Furthermore, the Republican candidate Goldwater tried to avoid discussion on Civil Rights, there were those within the party who used the movement to steal away Democrats who were unhappy with their party’s move toward supporting the movement. This was the campaign in which Strom Thurmond would become a Republican and Jackie Robinson would condemn his Republican party as being the party of “white men only.” Robinson would later leave the GOP.

Much is made of the FBI’s role with both King and other Civil Rights leaders. They helped solve the murders of Civil Rights leaders, but they also kept close eyes on the leaders of the movement, watching for communist connections. Through wiretaps, they learned of King’s infidelities an even used this to encourage King to commit suicide. They attempted to thwart King’s reception of the Noble Peace Prize, which he later received. They also called in Cardinal Spellman to give him the dirt on King to block a papal visit. While Spellman supposedly took the information to Rome, the meeting papal meeting still occurred partly due to the intervention of Rabbi Abraham Heschel. Like the first book in the series, King isn’t seen as totally a saint or sinner, but a man who struggled with depression and his own humanity.

Branch spends considerable time providing a background on the Nation of Islam and the conflict between its founder, Elijah Muhammad and Malcom X. The Nation of Islam created a vision of separation of the races and violence toward their enemies, which contrasted to King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference vision of a beloved community. The book begins with a deadly police encounter after a Nation of Islam meeting in South Central Los Angeles in 1962. Toward the end of the book, the Nation kills Malcom X after he left the Nation for a purer form of Islam. His view of religion had become less racially focused, and he softened his stance toward King’s nonviolent resistance.

This book also shows the tension within churches over supporting Civil Rights. Not all African American churches supported the Civil Rights movement, with some seeing it too dangerous. After all, there were many firebombed churches in the American South during the early 1960s. Northern Episcopal bishops struggled with what to say as they didn’t want to be seen as challenging their southern colleagues. This led to the wives of some bishops taking up the clause. One of the interesting stories was the wife of a Massachusetts bishop and mother of the state’s governor, Mary Peabody, who was arrested and jailed for protesting in St. Augustine.

I recommend this book to anyone wanting to better understand the Civil Rights movement in America. I don’t plan to wait another 19 years before I read Branch’s third volume. The final volume holds interest in me as I remember some of the events which happened.

This review is from 2006, after reading the first book in Branch’s series:

Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63

(New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 1064 pages including index, notes, and two sets of black and white photographs.

This book is an enormous undertaking, for both the author and the reader. The author provides the reader a biography of the Reverend Martin Luther King’s work through 1963, a view into the early years of the Civil Rights movement, as well as showing how the movement was affected by national and international events. This is the first of three massive volumes by Taylor Branch that spans the years of King’s ministry, from his ordination in 1954 to his death in 1968.

This volume also provides some detail about King’s family history and his earlier life through graduate school at Boston University. I decided to read this book after hearing Branch speak in Birmingham AL in June. It’s like reading a Russian novel with a multitude of characters and over 900 pages of text. However, it was worth the effort as I got an inside look as to what was going on in the world during the first six years of my life.

Branch does not bestow sainthood, nor does he throw stones. The greatness of Martin Luther King comes through as well as his shortcomings. He demonstrates King’s brilliance in the Montgomery Bus Campaign as well as in Birmingham. He also shows the times King struggled: his battles within his denomination, the National Baptist; King’s struggles with the NAACP; as well as his infidelities.

The FBI also had mixed review. Agents stood up to Southern law enforcement officers, insisting that the rights of African Americans be protected. They often warned Civil Rights leaders of threats and dangers they faced. However, once King refused to heed the FBI’s warnings that two of his associates were communists, the agency at Hoover’s insistence, set out to break King. Hoover’s inflexible can be seen as he reprimanded an agent for suggesting that King’s associates are not communists.

The Kennedy’s (John and Robert) also have mixed reviews. John Kennedy’s Civil Rights Speech (and on the night that Medgar Evers would be killed in Mississippi) is brilliant. Kennedy drew upon Biblical themes, labeling Civil Rights struggle a moral issue “as old as the Scriptures.” Yet the Kennedy brothers appear to base most of their decisions based on political reasons and not moral ones. This allows King to sometimes push Kennedy at his weakness, hinting that he has or can get the support of Nelson Rockefeller (a Republican).

Although we think today of the Democrat Party being the party of African Americans, this wasn’t necessarily the case in the 50s and early 60s. Many black leaders, especially within the National Baptist Convention leadership, identified themselves as Republicans, with Lincoln’s party.

Many of the black entertainers played in the movement. King was regularly in contact with Harry Belafonte, but also gains connections to Sammy Davis Jr., Lena Horne, Jackie Robinson, James Baldwin and others. The author also goes to great lengths to put the Civil Rights movement into context based on the Cold War politics. Both Eisenhower and Kennedy found themselves in embarrassing positions as they spoke out for democracy overseas while blacks within the United States were being denied rights.

The book ends in 1963, a watershed year for Civil Rights. King leads the massive and peaceful March on Washington. Medgar Evans and John Kennedy are both assassinated. And before the year is out, King has an hour-long chat with the President, Lyndon Johnson, a Southerner, who would see to it that the Voting Rights Acts become law.

As a white boy from the South, this book was eye opening. I found myself laughing that the same people who today bemoan the lack of prayer in the public sphere were arresting blacks for praying on the courthouse steps. The treatment of peaceful protesters was often horrible. There were obvious constitutional violations such as Wallace and the Alabama legislature raising the minimum bail for minor crimes in Birmingham 10-fold (to $2500) to punish those marching for Civil Rights.

I was also pleasantly surprised at behind-the-scenes connections between King and Billy Graham. Graham’s staff even provided logistical suggestions for King. King’s commitment to non-violence and his dependence upon the methods of Gandhi are evident. Finally, I found myself wondering if the segregationists like Bull O’Conner of Birmingham shouldn’t be partly responsible for the rise in crime among African American youth. They relished throwing those fighting for basic rights into jail, breaking a fear and taboo of jail. The taboo of being in jail has long kept youth from getting into trouble and was something the movement had to overcome to get mass arrest to challenge the system. In doing so, jail no longer was an experience to be ashamed off and with Pandora’s Box open, jail was no longer a determent to other criminal behavior.

I recommend this book if you have a commitment to digging deep into the Civil Rights movement. Branch is a wonderful researcher, and his use of FBI tapes and other sources give us a behind the scenes look at both what was happening within the Civil Rights movement as well as at the White House. However, there are so many details. For those wanting just an overview of the Civil Rights movement, this book may be a bit much. As for me, I’m looking forward to digging into the other two books of this trilogy: A Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963-65 and At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-68.