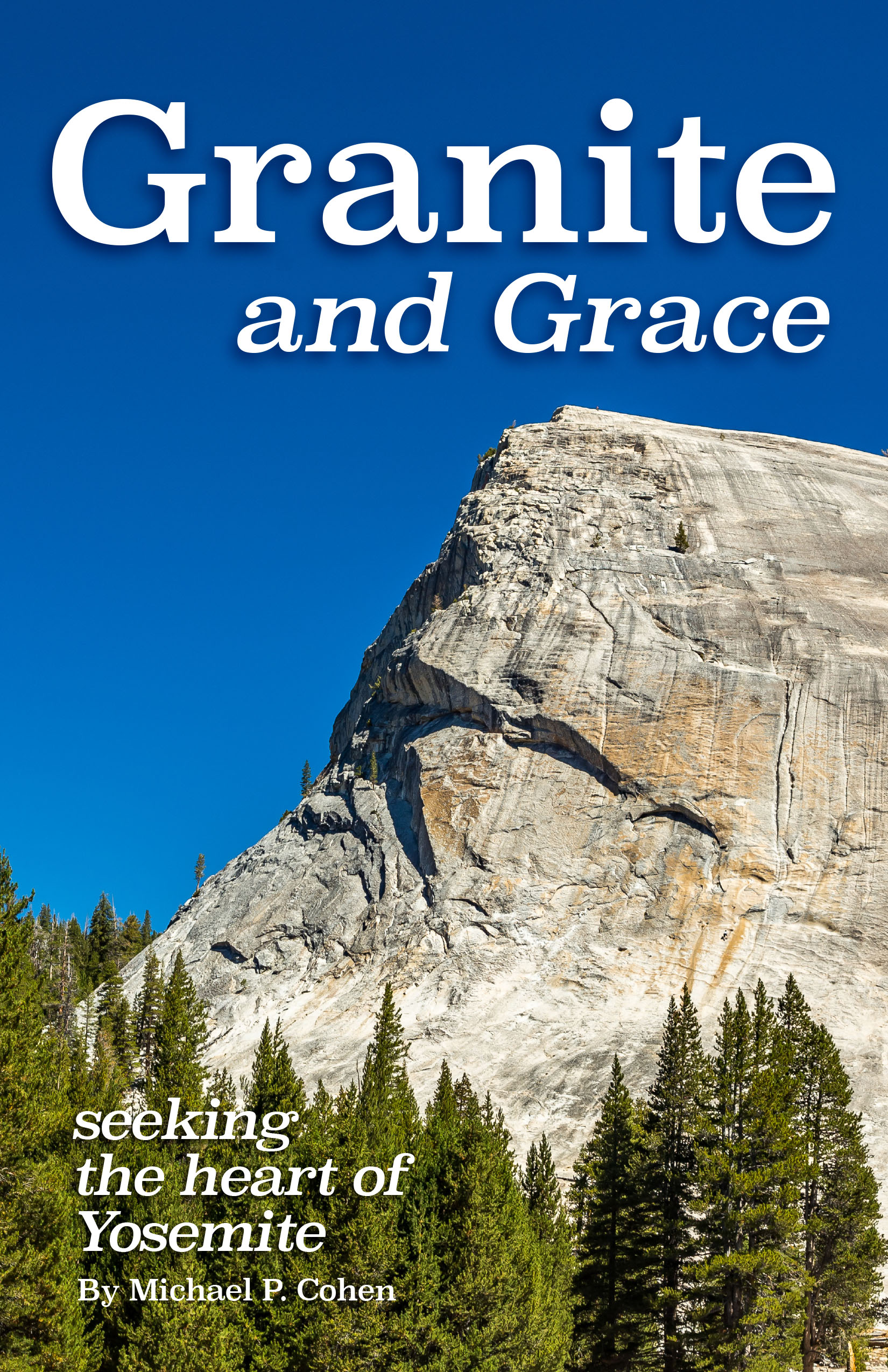

Michael P. Cohen, Granite and Grace: Seeking the Heart of Yosemite (Reno: University of Nevada, 2019), 220 pages. A few hand drawn maps and line drawings at the top of each chapter by Valerie Cohen.

When most people think of Yosemite, they think of the valley with its huge waterfalls and sheer-faced granite cliffs where, at night, you can see the flashlights of climbers’ bivouac in hammocks slung along the rock walls. But there is another side of Yosemite. This part of the park is high above the valley and surrounds Tuolumne Meadows. The top of the park is also granite, mostly sculptured by glaciers. It is here, in a series of essays, that Cohen focuses his study of the rock that made the park so famous. For nearly three decades, Cohen taught at Southern Utah University. During the summer, he and his wife would leave the sandstone of the Colorado River Plateau for June Lake, on the backside of Yosemite. The two of them have been coming to Yosemite since childhood. Early in their life together, Michael worked as a climbing guide in the park while Valerie worked as a summer ranger. Now in his 70s and no longer climbing the steep pitches, Cohen reflects on a lifetime living around Yosemite.

Granite and Grace centers around a series of essays that are often told from the point of view of a walker/hiker/climber in Yosemite. As Cohen recounts walks and climbs, he branches out to discuss various rock formations. Within these essays, he covers the geology of granite, how it was formed under the earth and is often found at the edge of continents. He writes about how the science around granite has changed especially within increase understanding of plate tectonics. He discussed the makeup of granite and why it’s appreciated by builders and climbers for its toughness. I had to laugh in appreciation of Cohen’s fondness for granite as he speaks of eating many meals upon it, but not wanting it as a countertop. (Granite does contain some radioactive minerals and houses built on granite have to be carefully constructed to avoid radon gas buildup). The reader will learn the role of ice in shaping the granite found in Yosemite’s high country. Weaving into his personal quests and the science behind granite, Cohen draws from a variety of literary sources. He quotes authors like John Muir and Jack Kerouac, poets such as Gary Snyder and Robinson Jeffers, and recalls songs from Paul Simon and Jefferson Airplane. While the book is part memoir that mixes in geology and literary interests, at its deepest, it is a philosophical exploration of an individual trying to understand a small section of the world.

In the concluding paragraph of the last chapter before the epilogue, Cohen writes a lyrical paragraph about granite’s “otherness and freedom.” His opening sentence, “I am attracted to granite and intimidated—especially by its textures—precisely because it is not flesh,” sets the stage for reflecting on how the “otherness” of this rock that doesn’t care or care if you care can provide a sense of peace. I was reminded of the last line in Norman McLean’s novella, A River Runs Through It. While Mclean finds peace at being in the river’s waters that gathers all that is, Cohen finds peace in that seemingly solid rock which is totally foreign and indifferent. Both views, I think, are valuable in our understanding the complexity of the human experience.

I recommend this book for anyone wanting to know more about Yosemite (this is not stuff you’ll find in guidebooks). There is something for most everyone in these pages. If you’re curious about geology, there are insights. If you want to know who we relate to the world in which we find ourselves, you’ll find parts that will speak to you.. Cohen is a deep thinker who searches for the precise word to describe his thoughts. In reading the book, if you’re like me, you’ll pull out the dictionary (or google) to look up many of his words. And, if you’re also like me, you’ll want to go back to Yosemite. His description of the Dana Plateau (which was an island above the impact of glaciation) made me realize there are places I still need to explore.

I was given a copy of this book by the author (see below) but was not compelled to write a review. This is the fourth book I’ve read by Cohen.

A Personal Note: My first visit to Yosemite was in 1985, thirty years after Cohen’s first visit. I had flown to San Francisco where my girlfriend at the time was in grad school. We drove to Yosemite for a few days. I was amazed as we snaked up the road that parallels the Merced River. By the time we got into the park, I had used up all my film and had to buy expensive film in a park store to continue photographing the amazing sights. It was between Thanksgiving and Christmas and was snowing. The next morning, while my girlfriend spent the day inside the cozy cabin reading and preparing for exams, I laced up my boots headed out at daybreak. I hiked up toward Nevada Falls. It was amazing (I again ran out of film). Along the way, I met a hiker with a loaded pack. He had skis and crampons strapped to his pack that was filled with winter camping gear and provisions. He was heading up over the top to Tuolumne Meadows where he planned to ski along the highway and down Tioga Pass to Lee Vining. There, he was going to be picked up three days later. I was intrigued. Tuolumne Meadows was beckoning me like Eden.

I have been back to the park a half-dozen times since 1985 and, with one exception, I have always come into the park from the east, into Tuolumne Meadows. When another guy and I completed our hike of the John Muir Trail, Michael Cohen (the author) joined us near Devil Post Pile. As I was living in Cedar City at the time, I had gotten to know Cohen when I audited his class on creative non-fiction. Michael hiked with us for several days as we made our way down Lyell Canyon and into the Meadows. Wanting to avoid the crowds of Yosemite Valley, Michael’s wife Valerie picked him there, while the two of us continued on for another two nights into the valley. When most people think of the park, they think of Yosemite Valley with its huge waterfalls, sheer granite cliffs, and hordes of tourist. Few make it over to Tuolumne Meadows. Cohen’s book will help those who only travel through the valley understand what they missed in the high country.

Michael also appears in another book I reviewed in this blog, Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust: A History of Walking.

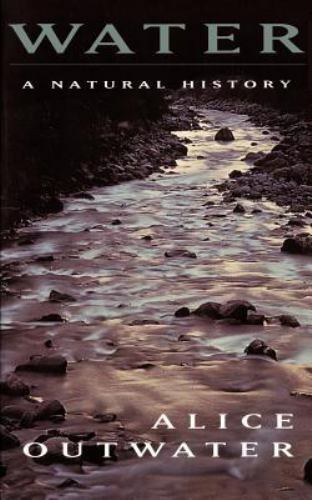

Alice Outwater, Water: A Natural History (New York: Basic Books, 1996) 212 pages with index and notes. Line drawings by Billy Brauer.

In this collection of what seems to be independent essays, the author describes the history and evolution of water in North America. She begins with the fur trade and nature’s engineers, the beaver. In subsequent chapters, she writes about prairie dogs, buffaloes, alligators, freshwater shellfish, as well as the forests and grasslands. She explores the path of rainfall and how its been altered as we have altered the environment. She discusses the role of the toilet and sewer systems. Toward the end of the book (175ff), Outwater brings together all these seemingly diverse ideas as she discusses our attempts to “save the environment.” She points out the fallacy in many environmental efforts. We attempt to preserve an “endangered species… as if they were items in a catalog… [while] missing the larger ecological picture.” (181). At first, I was wondering where Outwater was going with these essays as they seemed to be independent of one another, but by the end of the book, I understood her point. She encourages us to see how the natural work really does work together.

Water: A Natural History is really a history of human impact upon the waters of North America (mainly the United States). Outwater recalls how we have misused our water and are now changing our views and our behavior as we strive to clean up our rivers and streams. She appears optimistic even while acknowledging there is more to be done. And example of her optimism is from seeing how the non-native zebra mussel, which was introduced by an ocean-going ship into the Great Lakes, is taking over the role of native mussels that have been wiped out by human activity. Having lived in the Great Lakes region for a decade, I know her view isn’t shared by many who see the zebra mussel as problematic.

Much of the concluding chapters of this book comes from Outwater’s work as an environmental engineer in the Boston Harbor cleanup project. Her writing is clear and concise. She caused me to ponder much about water and how we depend on it. I would recommend this book to anyone interested in one of things necessary for life—water. And I also find her name, “Outwater” to be appropriate for someone who writes on the topic! This is my second book by Outwater. I had previously reviewed her book, Wild at Heart which also covers many of these same themes.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

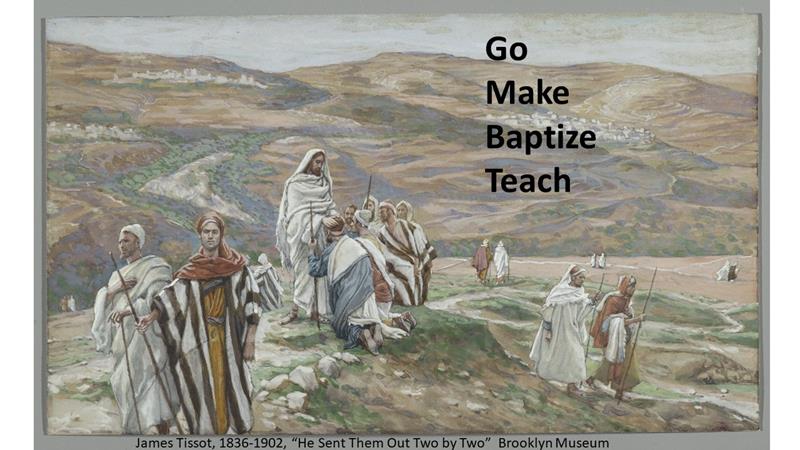

When Jesus sends the disciples, he insists they go light. No extra clothes, no extra gear, no extra food, and no extra cash. They go by themselves, taking only the blessing Jesus bestowed upon them. They are to learn first-hand that Jesus is sufficient—he has given them power over evil as well as the ability to bring healing to those who are sick and to bring to life those who are dead. Going out without possessions, they will be continually reminded that they are dependent upon God and the generosity of others. Furthermore, they would be continually reminded that they are working for Jesus.

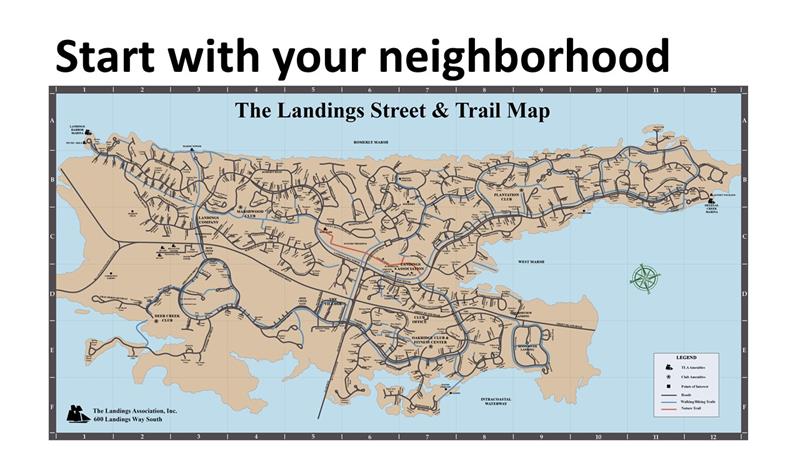

When Jesus sends the disciples, he insists they go light. No extra clothes, no extra gear, no extra food, and no extra cash. They go by themselves, taking only the blessing Jesus bestowed upon them. They are to learn first-hand that Jesus is sufficient—he has given them power over evil as well as the ability to bring healing to those who are sick and to bring to life those who are dead. Going out without possessions, they will be continually reminded that they are dependent upon God and the generosity of others. Furthermore, they would be continually reminded that they are working for Jesus. Jesus advice to the disciples is to start in their own neighborhoods. The mission to the Gentiles will come later; they first must take the message to the Jones and Smiths who live down the street. As they travel, they’re to live modestly and with the people. They are to be gracious and content with what they’re offered. They’re to “be courteous.” They’re not out to bring judgment or to browbeat folks, they’re just to go about helping people and sharing with them the good news that the Savior has come. If they’re not welcomed, they’re not to make big deal about it, they’re just to move on to the next neighborhood, not taking it as a failure. They’re not to mope around showing disappointment.

Jesus advice to the disciples is to start in their own neighborhoods. The mission to the Gentiles will come later; they first must take the message to the Jones and Smiths who live down the street. As they travel, they’re to live modestly and with the people. They are to be gracious and content with what they’re offered. They’re to “be courteous.” They’re not out to bring judgment or to browbeat folks, they’re just to go about helping people and sharing with them the good news that the Savior has come. If they’re not welcomed, they’re not to make big deal about it, they’re just to move on to the next neighborhood, not taking it as a failure. They’re not to mope around showing disappointment.

Another thing we learn that the world isn’t how it should be. We know this is true. If there was any question about it, the last few months dispelled our doubts. But at this point in the First Century, Rome had beaten all its enemies, and those who thought world peace had come. Of course, Jesus sees problems. There are people suffering. Jesus is compassionate. He realizes the struggle many face, especially the poor and slaves. Many are battling demons and the powers of evil. Many are grief-filled, or hurting physically and emotionally. Jesus’ plan is to turn the world upside down, offering grace and hope that can only come from God.

Another thing we learn that the world isn’t how it should be. We know this is true. If there was any question about it, the last few months dispelled our doubts. But at this point in the First Century, Rome had beaten all its enemies, and those who thought world peace had come. Of course, Jesus sees problems. There are people suffering. Jesus is compassionate. He realizes the struggle many face, especially the poor and slaves. Many are battling demons and the powers of evil. Many are grief-filled, or hurting physically and emotionally. Jesus’ plan is to turn the world upside down, offering grace and hope that can only come from God.

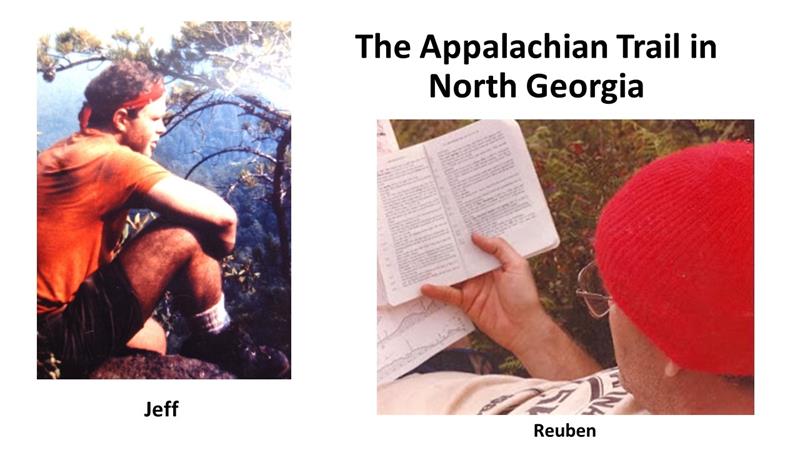

A final truth I want us to consider is that mission involves more than just telling people about Jesus. You know, Reuben and I could have spent all day telling Paul about how much fun we had backpacking and it wouldn’t have made any difference. It was only by helping him go through his gear and showing him how to lighten his load were we able to help. It’s the same with our calling as disciples. We’re not to just share the good news; we’re to demonstrate godly values in our lives and to show others how it can make a difference. That famous saying attributed to Francis of Assisi, “preach the gospel, if necessary, use words,” comes to mind. As the 18th verse reads, “you’ve been treated generously, so live generously.” Doing is just as important as telling, as Jesus makes clear in this passage. He didn’t give the disciples golden words to woo people; he gave them the ability to minister, to heal, and to confront evil.

A final truth I want us to consider is that mission involves more than just telling people about Jesus. You know, Reuben and I could have spent all day telling Paul about how much fun we had backpacking and it wouldn’t have made any difference. It was only by helping him go through his gear and showing him how to lighten his load were we able to help. It’s the same with our calling as disciples. We’re not to just share the good news; we’re to demonstrate godly values in our lives and to show others how it can make a difference. That famous saying attributed to Francis of Assisi, “preach the gospel, if necessary, use words,” comes to mind. As the 18th verse reads, “you’ve been treated generously, so live generously.” Doing is just as important as telling, as Jesus makes clear in this passage. He didn’t give the disciples golden words to woo people; he gave them the ability to minister, to heal, and to confront evil. This is still our goal. Live simply and generously, ministering to the needs of others. In other words, let the love of Jesus flow from your hearts, and be gracious. These days, the world can use a little help. Let’s flood it with grace. Amen.

This is still our goal. Live simply and generously, ministering to the needs of others. In other words, let the love of Jesus flow from your hearts, and be gracious. These days, the world can use a little help. Let’s flood it with grace. Amen.

We’re living in trying times, but there is hope in this passage. In the last verse, after telling us that it’s our responsibility to make and baptize and teach disciples, Jesus reminds us that he will be with us till history comes to an end. Jesus is going to be with us wherever we go in this world to do the gospel’s work. That’s the hope we take with us as we challenge such injustice. We’re not alone. We’ll get through this trying time of pandemic and racial tensions if we can just remember the two essential things Jesus taught: Love God and love your neighbor.

We’re living in trying times, but there is hope in this passage. In the last verse, after telling us that it’s our responsibility to make and baptize and teach disciples, Jesus reminds us that he will be with us till history comes to an end. Jesus is going to be with us wherever we go in this world to do the gospel’s work. That’s the hope we take with us as we challenge such injustice. We’re not alone. We’ll get through this trying time of pandemic and racial tensions if we can just remember the two essential things Jesus taught: Love God and love your neighbor. You know, I love my neighbors, but I also love a good tomato sandwich. During this time of the year, when I have tomatoes on the vine, I eat a tomato sandwich every day. I peel the tomatoes and then slice ‘em thick. They are juicy and messy. I take two slices of wheat bread, cover a side of each with Miracle Whip, grind some pepper over it, then lay on the tomatoes and create a sandwich. If I want to be uptown, I might add a little celery seed or some provolone cheese. Its good eating and I tell you this because our passage can be envisioned as a sandwich.

You know, I love my neighbors, but I also love a good tomato sandwich. During this time of the year, when I have tomatoes on the vine, I eat a tomato sandwich every day. I peel the tomatoes and then slice ‘em thick. They are juicy and messy. I take two slices of wheat bread, cover a side of each with Miracle Whip, grind some pepper over it, then lay on the tomatoes and create a sandwich. If I want to be uptown, I might add a little celery seed or some provolone cheese. Its good eating and I tell you this because our passage can be envisioned as a sandwich. In closing, let me encourage you to do two things. First, go to the Savannah Presbytery website and read our recent statement on racism.

In closing, let me encourage you to do two things. First, go to the Savannah Presbytery website and read our recent statement on racism.

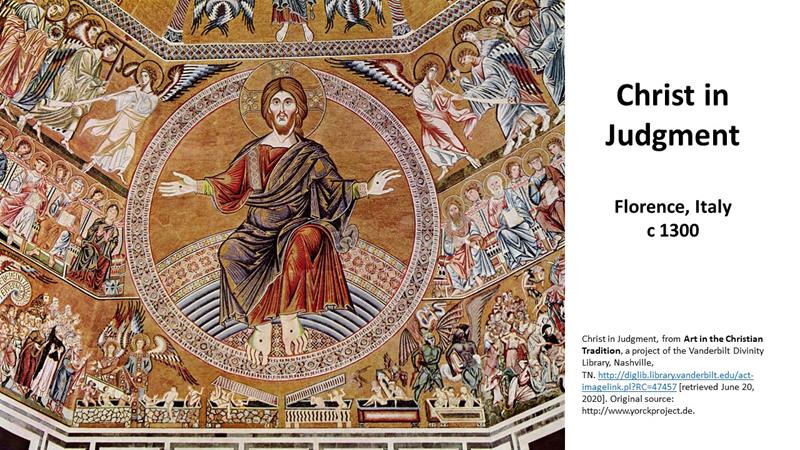

There was an elderly woman who came home from a Bible study one evening and discovered a burglar in her home. In the darken house, she yelled at the intruder, “Stop, Acts 2:38.” The thief turned and she yelled again, “Stop, Acts 2:38.” He froze. He raised his hands as she calmly called the police. After the officer had handcuffed the man, he asked why he’d surrendered to a woman shouting out a Bible verse. “A Bible verse? I thought she had an axe and two 38s”.

There was an elderly woman who came home from a Bible study one evening and discovered a burglar in her home. In the darken house, she yelled at the intruder, “Stop, Acts 2:38.” The thief turned and she yelled again, “Stop, Acts 2:38.” He froze. He raised his hands as she calmly called the police. After the officer had handcuffed the man, he asked why he’d surrendered to a woman shouting out a Bible verse. “A Bible verse? I thought she had an axe and two 38s”. Peter, after his great sermon, that follows the account we’ve just read, called on those within his hearing to “Repent, be baptized, every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven and you will receive the power of the Holy Spirit.” Acts 2:38.

Peter, after his great sermon, that follows the account we’ve just read, called on those within his hearing to “Repent, be baptized, every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven and you will receive the power of the Holy Spirit.” Acts 2:38. oo often, we think we need force to back up our words, or as in the joke, the possibility of force. But Scripture constantly reminds us our hope is not in what we do or what we have, but in what God has done and is doing in Jesus Christ. We see this with Pentecost, when those flames of the Spirit poured out on a motley group. God takes the initiative. Without God, our efforts are in vain.

oo often, we think we need force to back up our words, or as in the joke, the possibility of force. But Scripture constantly reminds us our hope is not in what we do or what we have, but in what God has done and is doing in Jesus Christ. We see this with Pentecost, when those flames of the Spirit poured out on a motley group. God takes the initiative. Without God, our efforts are in vain. These men and women are not the type of people you’d think could change the world. They’re marginalized. And, to be honest, they don’t change the world. That’s part of the point of the story. God’s the primary actor. Without God’s intervention, nothing would have happened. And the same is true in our lives. God can use us; we don’t have to be sophisticated or multi-talented. The disciples were not great leaders or thinkers, government officials or military heroes. What God needs are people who are faithful. These believers displayed their faithfulness. Many of them were faithful even unto death. With God, all things are possible.

These men and women are not the type of people you’d think could change the world. They’re marginalized. And, to be honest, they don’t change the world. That’s part of the point of the story. God’s the primary actor. Without God’s intervention, nothing would have happened. And the same is true in our lives. God can use us; we don’t have to be sophisticated or multi-talented. The disciples were not great leaders or thinkers, government officials or military heroes. What God needs are people who are faithful. These believers displayed their faithfulness. Many of them were faithful even unto death. With God, all things are possible.

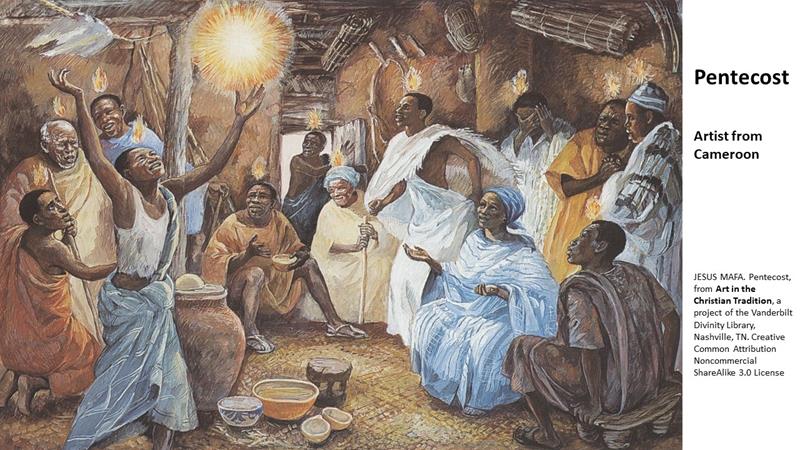

The final aspect of Pentecost for us to consider is how this event serves as a model for God’s intention for the world. Consider the group who’d gathered on this morning. They were all Palestinian Jews. First century Judaism was more multi-cultural than they were. They gather, a homogeneous lot, without an idea as to what will happen. Soon a violent wind destroys the morning calm. Luke describes the coming of the Spirit as a gale blowing into the house. Picture the curtains blowing, as they used to do in the days before air conditioning when a storm was rising. It was frightening. “What’s happening,” they wonder? Luke goes on to say that the wind was like tongues of fire; like a wildfire that gains momentum consuming all that’s around. And those who had gathered begin to speak, in all different kinds of languages.

The final aspect of Pentecost for us to consider is how this event serves as a model for God’s intention for the world. Consider the group who’d gathered on this morning. They were all Palestinian Jews. First century Judaism was more multi-cultural than they were. They gather, a homogeneous lot, without an idea as to what will happen. Soon a violent wind destroys the morning calm. Luke describes the coming of the Spirit as a gale blowing into the house. Picture the curtains blowing, as they used to do in the days before air conditioning when a storm was rising. It was frightening. “What’s happening,” they wonder? Luke goes on to say that the wind was like tongues of fire; like a wildfire that gains momentum consuming all that’s around. And those who had gathered begin to speak, in all different kinds of languages. Friends, we live in an uncertain time. We must place our faith in God as revealed in Jesus Christ, and live humbly and compassionately, showing the world a different way to live with one another. Violence isn’t the answer. Love is. God loves this world and calls on his church to love the world. When we marginalize others, when we turn our heads at injustice, we fail to live up to our calling.

Friends, we live in an uncertain time. We must place our faith in God as revealed in Jesus Christ, and live humbly and compassionately, showing the world a different way to live with one another. Violence isn’t the answer. Love is. God loves this world and calls on his church to love the world. When we marginalize others, when we turn our heads at injustice, we fail to live up to our calling. Let me tell you a story. I was in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia and was walking with other tourists in the business section of the city. Across a four-lane road, coming toward us, was a man and woman. They were arguing. Then the man pulled back and hit the woman with his fist to her head, knocking her down. In shock, we looked at each other. Others had seen it, too, but no one except us-a group of English-speaking tourist-seemed fazed. We were outraged, yet never felt so helpless. If it had been an English-speaking country, we’d all been on the phone with the police. But here, few knew English and we couldn’t speak Mongolian. We needed those tongues of fire!

Let me tell you a story. I was in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia and was walking with other tourists in the business section of the city. Across a four-lane road, coming toward us, was a man and woman. They were arguing. Then the man pulled back and hit the woman with his fist to her head, knocking her down. In shock, we looked at each other. Others had seen it, too, but no one except us-a group of English-speaking tourist-seemed fazed. We were outraged, yet never felt so helpless. If it had been an English-speaking country, we’d all been on the phone with the police. But here, few knew English and we couldn’t speak Mongolian. We needed those tongues of fire! Pentecost shows us that not only does God show up, God gives us the tools needed to do the work for which we’re called. That motley group of disciples are able to preach in the languages of those gathered in Jerusalem. Today, we no longer have to wait for God to show up. God’s Spirit’s with us. Unlike Mongolia, in our country, in our neighborhood, most people understand us. We have no excuse. We must be compassionate toward those suffering from COVID-19. We should grieve the deaths of over 100,000 of our citizens, we need to do our part to keep the virus from spreading further, and we need to speak out against racial injustice. At Pentecost, God gave us a vision of the nations and people being brought together. It’s now our turn. We must help make the vision a reality. Amen.

Pentecost shows us that not only does God show up, God gives us the tools needed to do the work for which we’re called. That motley group of disciples are able to preach in the languages of those gathered in Jerusalem. Today, we no longer have to wait for God to show up. God’s Spirit’s with us. Unlike Mongolia, in our country, in our neighborhood, most people understand us. We have no excuse. We must be compassionate toward those suffering from COVID-19. We should grieve the deaths of over 100,000 of our citizens, we need to do our part to keep the virus from spreading further, and we need to speak out against racial injustice. At Pentecost, God gave us a vision of the nations and people being brought together. It’s now our turn. We must help make the vision a reality. Amen.

Some of you may know the Reverend Proctor Chambless. He’s a retired minister member of the Savannah Presbytery, and has served a number of congregations within our presbytery and across the South. When I came to this presbytery, Proctor was serving an interim position in another presbytery upstate. He wasn’t here. During the first person examined for ordination as a Minister of the Word and Sacrament at Presbytery, someone stood up and said that since Proctor wasn’t present, he was going to ask Proctor’s question. The question: “Do you love Jesus?” The presbytery, as a body, snickered. I realized I wasn’t in on the joke. I asked someone about this and was told that Proctor always asked that question. When Proctor returned, I figured out who he was before I met him. We had another candidate to examine and Proctor stood and asked this question. It’s kind of a fun thing. The rest of us are thinking probing questions to prod the examinee on the fine points of Reformed Theology, as Proctor, with his deep southern drawl, asks the essential question. “Do you love Jesus?” That’s the question Jesus asks Peter three times. And it’s a question we’re all to ask ourselves. Furthermore, as we’re going to see when we delve into this text, there is one way of knowing that we love Jesus. Do we care for others?

Some of you may know the Reverend Proctor Chambless. He’s a retired minister member of the Savannah Presbytery, and has served a number of congregations within our presbytery and across the South. When I came to this presbytery, Proctor was serving an interim position in another presbytery upstate. He wasn’t here. During the first person examined for ordination as a Minister of the Word and Sacrament at Presbytery, someone stood up and said that since Proctor wasn’t present, he was going to ask Proctor’s question. The question: “Do you love Jesus?” The presbytery, as a body, snickered. I realized I wasn’t in on the joke. I asked someone about this and was told that Proctor always asked that question. When Proctor returned, I figured out who he was before I met him. We had another candidate to examine and Proctor stood and asked this question. It’s kind of a fun thing. The rest of us are thinking probing questions to prod the examinee on the fine points of Reformed Theology, as Proctor, with his deep southern drawl, asks the essential question. “Do you love Jesus?” That’s the question Jesus asks Peter three times. And it’s a question we’re all to ask ourselves. Furthermore, as we’re going to see when we delve into this text, there is one way of knowing that we love Jesus. Do we care for others? Jesus uses his full legal name. “Simon, son of John.” Did any of you have parents, or maybe a teacher, who when you were in trouble, would use your full name? “Charles Jeffrey!” I would hear that and immediately knew I had done something wrong. Was Peter in trouble? I don’t think so. But Jesus emphasizes the importance of his questioning. When someone uses your full name, it grabs your attention. Jesus asks Peter if he loves him more than these. We can assume Jesus is pointing over toward the other disciples. We’re told that Peter, in two of the gospels, brags at the Last Supper about how much more he loves Jesus than the others, so much so that he’ll never abandon Jesus.

Jesus uses his full legal name. “Simon, son of John.” Did any of you have parents, or maybe a teacher, who when you were in trouble, would use your full name? “Charles Jeffrey!” I would hear that and immediately knew I had done something wrong. Was Peter in trouble? I don’t think so. But Jesus emphasizes the importance of his questioning. When someone uses your full name, it grabs your attention. Jesus asks Peter if he loves him more than these. We can assume Jesus is pointing over toward the other disciples. We’re told that Peter, in two of the gospels, brags at the Last Supper about how much more he loves Jesus than the others, so much so that he’ll never abandon Jesus. Now, after everything that has happened—the betrayal, the crucifixion, the resurrection—Jesus asks if Peter really does love him and, of course, Peter responds positively. “Yes, Lord, you know that I love you.” Jesus then tells Peter to feed his lambs. This questioning goes on for three times, with just slight variations.

Now, after everything that has happened—the betrayal, the crucifixion, the resurrection—Jesus asks if Peter really does love him and, of course, Peter responds positively. “Yes, Lord, you know that I love you.” Jesus then tells Peter to feed his lambs. This questioning goes on for three times, with just slight variations. We’re not given a sense of just how this prediction of Peter’s death was received, but Peter must have pondered it, for he asks about another of the disciples. Jesus tells Peter a great truth. “Don’t worry about him and his death.” It’s almost as if Jesus is saying, “You have enough troubles. Don’t worry about what God seems to give someone else to worry over.” In other words, accept God’s gift as grace and be thankful.

We’re not given a sense of just how this prediction of Peter’s death was received, but Peter must have pondered it, for he asks about another of the disciples. Jesus tells Peter a great truth. “Don’t worry about him and his death.” It’s almost as if Jesus is saying, “You have enough troubles. Don’t worry about what God seems to give someone else to worry over.” In other words, accept God’s gift as grace and be thankful. Here we are, fifty or so generations Peter.

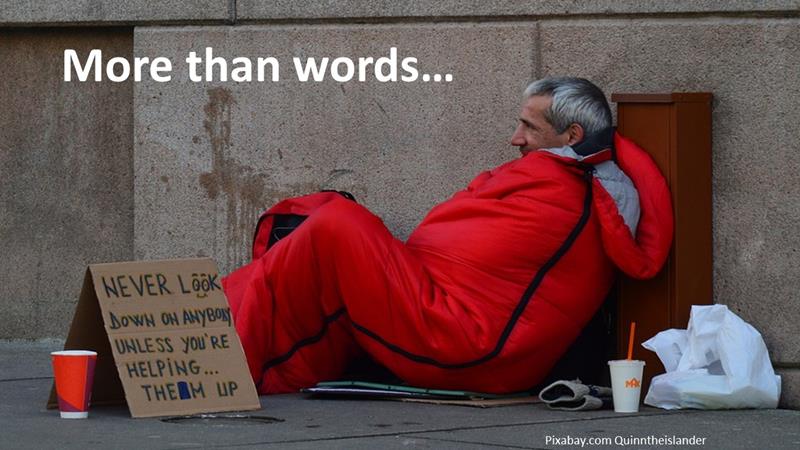

Here we are, fifty or so generations Peter. During these trying times, when we are hiding out in our homes, we might wonder how we can help anyone. There are ways. The Session, at the request of the Mission and Benevolence Committee, has called for a special offering to help care for the homeless in our community. Do what you can to help. The homeless ministries of Savannah are struggling to meet the needs of those who live under the bridges and on the streets.

During these trying times, when we are hiding out in our homes, we might wonder how we can help anyone. There are ways. The Session, at the request of the Mission and Benevolence Committee, has called for a special offering to help care for the homeless in our community. Do what you can to help. The homeless ministries of Savannah are struggling to meet the needs of those who live under the bridges and on the streets.

Nancy Koester, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Spiritual Life (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014), 371 pages, B&W photos, notes.

Nancy Koester, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Spiritual Life (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014), 371 pages, B&W photos, notes. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

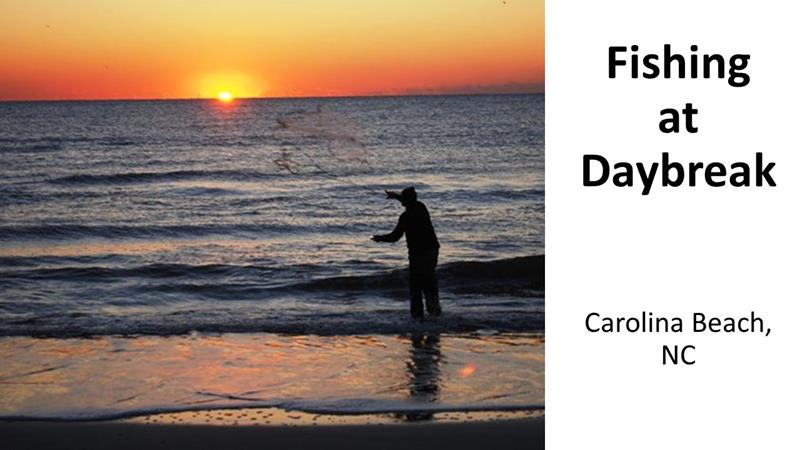

The best fish are fresh from the water. Even greasy bluefish make a great breakfast when grilled over a charcoal fire on the beach. I was probably 10 or 11 when I first had such a treat. We were fishing on Masonboro Island. It was in the fall, when the bluefish run. We got up when it was still pitch dark and chilly. My dad started a charcoal fire, which helped us stay warm. But instead of sitting around the fire, we soon had lines in the dark water, casting out into surf. In darkness, we fished with bait. On the end of the line, we had a rig with a weight and two hooks, each containing a strip of mullet. When the fish hit, we’d yank the rod to set the hook, then reel hard. Soon, if lucky, a flapping fish could be made out from the distant light of the lantern. We’d have to bring the fish into the light in order to safely get out the hook.

The best fish are fresh from the water. Even greasy bluefish make a great breakfast when grilled over a charcoal fire on the beach. I was probably 10 or 11 when I first had such a treat. We were fishing on Masonboro Island. It was in the fall, when the bluefish run. We got up when it was still pitch dark and chilly. My dad started a charcoal fire, which helped us stay warm. But instead of sitting around the fire, we soon had lines in the dark water, casting out into surf. In darkness, we fished with bait. On the end of the line, we had a rig with a weight and two hooks, each containing a strip of mullet. When the fish hit, we’d yank the rod to set the hook, then reel hard. Soon, if lucky, a flapping fish could be made out from the distant light of the lantern. We’d have to bring the fish into the light in order to safely get out the hook. Leaving our fish on sand, we rebait our hooks and again cast out into the surf. Slowly, the sky changes. The stars began to extinguish themselves. A ribbon of light appears on the horizon, and it gradually growed. We began to be able to make out the beach and could see where the waves were breaking. Soon afterwards, the sun would slowly rise, its rays seemingly racing across the water toward me, as if they whose rays were destined just for me.

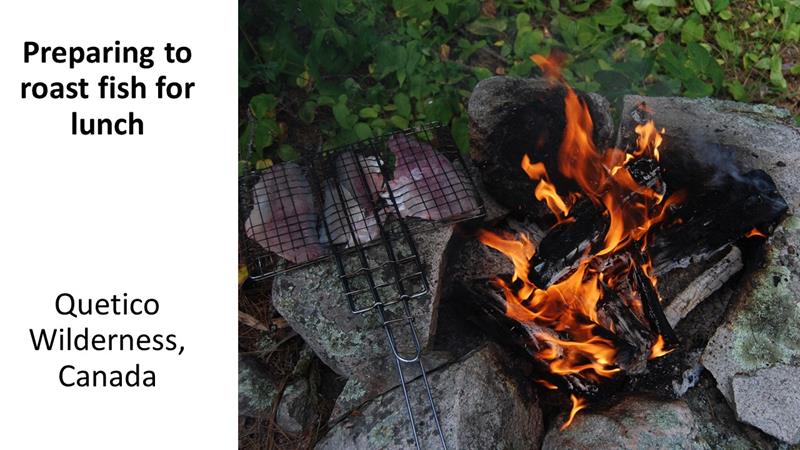

Leaving our fish on sand, we rebait our hooks and again cast out into the surf. Slowly, the sky changes. The stars began to extinguish themselves. A ribbon of light appears on the horizon, and it gradually growed. We began to be able to make out the beach and could see where the waves were breaking. Soon afterwards, the sun would slowly rise, its rays seemingly racing across the water toward me, as if they whose rays were destined just for me. When there was a lull in the action, we’d stop and clean a few fish, washing them off in the surf, and then lay them on a grill over the coals. In a few minutes, we’d be “eatin’ good.” Afterwards, we’d change the rigging on our rods to plugs and spoons and head back to the water’s edge. Good memories of good times.

When there was a lull in the action, we’d stop and clean a few fish, washing them off in the surf, and then lay them on a grill over the coals. In a few minutes, we’d be “eatin’ good.” Afterwards, we’d change the rigging on our rods to plugs and spoons and head back to the water’s edge. Good memories of good times. Perhaps it was because I grew up in a home where fishing ranked just below church attendance in priority that Peter’s statement, “I’m going fishing” seems normal. And to the six disciples with him, it sounds like a plan. They head to the water and fished the night. They had terrible luck. That happens. Some mornings there are no bluefish for breakfast.

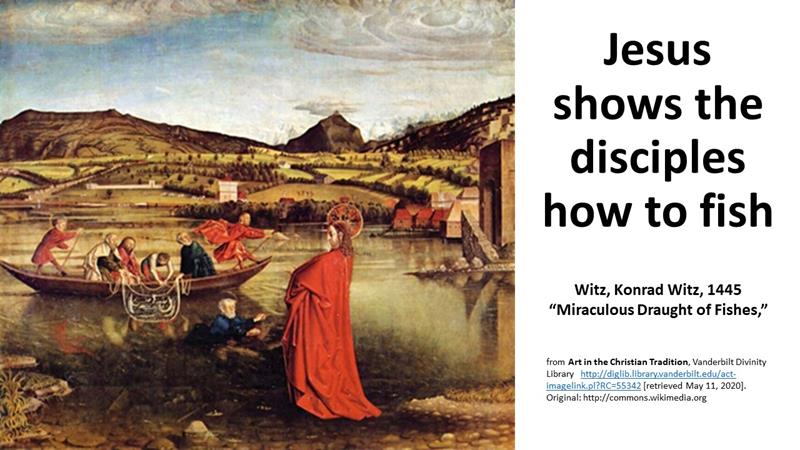

Perhaps it was because I grew up in a home where fishing ranked just below church attendance in priority that Peter’s statement, “I’m going fishing” seems normal. And to the six disciples with him, it sounds like a plan. They head to the water and fished the night. They had terrible luck. That happens. Some mornings there are no bluefish for breakfast. As I’ve emphasized in these sermons on Jesus’ resurrection, the disciples learn a true lesson. They are not in control. Jesus is in control. We often have this image of going to Jesus, but in truth, Jesus first comes to us. In today’s story, Jesus knows where many of his disciples are. They’re by the lakeshore, fishing, because that’s what they know how to do. So, like when he first called them, he returns to call them again. Next week, we’ll look at how Jesus sends out Peter with a mission, but before we go there, I want us to spend some time in this story.

As I’ve emphasized in these sermons on Jesus’ resurrection, the disciples learn a true lesson. They are not in control. Jesus is in control. We often have this image of going to Jesus, but in truth, Jesus first comes to us. In today’s story, Jesus knows where many of his disciples are. They’re by the lakeshore, fishing, because that’s what they know how to do. So, like when he first called them, he returns to call them again. Next week, we’ll look at how Jesus sends out Peter with a mission, but before we go there, I want us to spend some time in this story. On this night, the fishing hadn’t been good. Jesus then does something else that goes against fishermen etiquette. “Why don’t you fish from the other side?” That’s like suggesting a different lure or fly. “Take off that spinner and put on a jitterbug; or get rid of that wooly bugger and put on a popping bug.” But Jesus’ advice pays off as they catch so many fish the net is about to break. Only then does the Beloved Disciple realizes it’s Jesus. Before he can act, Peter throws on some clothes, jumps in and swims toward shore.

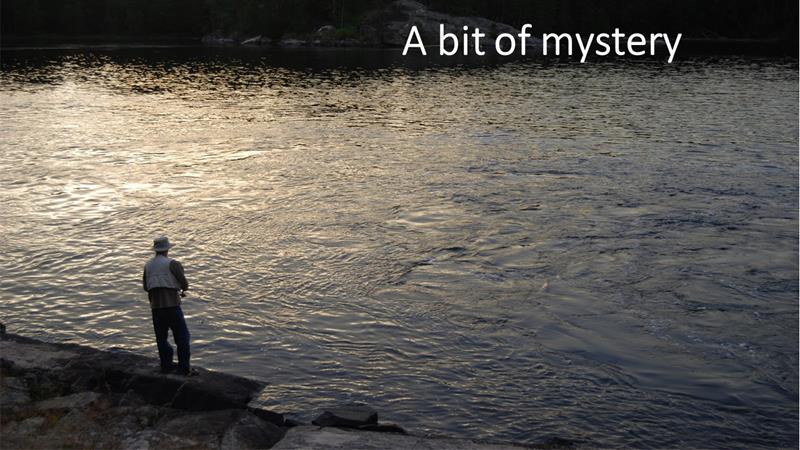

On this night, the fishing hadn’t been good. Jesus then does something else that goes against fishermen etiquette. “Why don’t you fish from the other side?” That’s like suggesting a different lure or fly. “Take off that spinner and put on a jitterbug; or get rid of that wooly bugger and put on a popping bug.” But Jesus’ advice pays off as they catch so many fish the net is about to break. Only then does the Beloved Disciple realizes it’s Jesus. Before he can act, Peter throws on some clothes, jumps in and swims toward shore. Like the other post-resurrection appearances, there’s also bit of mystery. Why do we even have verse twelve? After Jesus calls them in for breakfast, we’re told that no one dared to ask, “Who are you?” They knew it was Jesus, but the text leaves us wondering what’s going on. Furthermore, they don’t recognize Jesus right off. It’s only when they follow his suggestion that they encounter him. There’s probably a lesson in that, too. When we listen to Jesus and do what he says, our relationship grows.

Like the other post-resurrection appearances, there’s also bit of mystery. Why do we even have verse twelve? After Jesus calls them in for breakfast, we’re told that no one dared to ask, “Who are you?” They knew it was Jesus, but the text leaves us wondering what’s going on. Furthermore, they don’t recognize Jesus right off. It’s only when they follow his suggestion that they encounter him. There’s probably a lesson in that, too. When we listen to Jesus and do what he says, our relationship grows. There are three things that happen to the disciples in this passage that we should take to heart. First, Jesus comes to us. Jesus shows up at the most unexpected places. In these stories, he doesn’t show up at church or the synagogue or the temple. Instead, it’s at work, after or before visiting hours. Think about the post-resurrection appearances. Except for meeting the disciples on the road to Emmaus, Jesus always shows up on the shoulders of the day (at daybreak and in the evening). In this case, Jesus arrives as the disciples are finishing up their night shift at a job that wasn’t going to be paying much this day. As followers of Jesus, we must be ready for whenever our Savior decides to pop by. Jesus is not just Lord over Sunday or over religion, he is Lord of all, and can meet us wherever we find ourselves. This is good news in a time that many of us find ourselves prisoners in our own homes! Yes, Jesus can show up even there, you’ll just have to let him in.

There are three things that happen to the disciples in this passage that we should take to heart. First, Jesus comes to us. Jesus shows up at the most unexpected places. In these stories, he doesn’t show up at church or the synagogue or the temple. Instead, it’s at work, after or before visiting hours. Think about the post-resurrection appearances. Except for meeting the disciples on the road to Emmaus, Jesus always shows up on the shoulders of the day (at daybreak and in the evening). In this case, Jesus arrives as the disciples are finishing up their night shift at a job that wasn’t going to be paying much this day. As followers of Jesus, we must be ready for whenever our Savior decides to pop by. Jesus is not just Lord over Sunday or over religion, he is Lord of all, and can meet us wherever we find ourselves. This is good news in a time that many of us find ourselves prisoners in our own homes! Yes, Jesus can show up even there, you’ll just have to let him in. Let me tell you a story to illustrate this. Many of the photos I’ve using today came from a 2008 trip into the Quetico Wilderness in Western Ontario. The guy at the camp stove you see now is Doc Spindler. One morning, he was talking about having pancakes and so proud of himself for prepacking everything he needed. To be helpful, Jim Bruce (who visited us here at SIPC in February and seen in the picture with the full plate) and I went out early that morning, braving the bears as we picked a quart of so of blueberries. We brought them back and Doc was so happy to have blueberries to mix into pancakes. You use what you’re given. Doc knows this. Although a great guy, however, Doc isn’t Jesus. Instead of the baggie with pancake mix, he used a package of meal for frying fish and the blueberry pancakes ended up coming out like goulash. But with a little syrup and butter and an empty stomach, it was still good.

Let me tell you a story to illustrate this. Many of the photos I’ve using today came from a 2008 trip into the Quetico Wilderness in Western Ontario. The guy at the camp stove you see now is Doc Spindler. One morning, he was talking about having pancakes and so proud of himself for prepacking everything he needed. To be helpful, Jim Bruce (who visited us here at SIPC in February and seen in the picture with the full plate) and I went out early that morning, braving the bears as we picked a quart of so of blueberries. We brought them back and Doc was so happy to have blueberries to mix into pancakes. You use what you’re given. Doc knows this. Although a great guy, however, Doc isn’t Jesus. Instead of the baggie with pancake mix, he used a package of meal for frying fish and the blueberry pancakes ended up coming out like goulash. But with a little syrup and butter and an empty stomach, it was still good. Finally, Jesus feeds us. In this case, he fed the disciples a hearty breakfast of fish and bread. But Jesus, who calls all who are weary to accept his yoke, will restore our tired souls and feed our minds and bodies with his presence and comfort.

Finally, Jesus feeds us. In this case, he fed the disciples a hearty breakfast of fish and bread. But Jesus, who calls all who are weary to accept his yoke, will restore our tired souls and feed our minds and bodies with his presence and comfort.