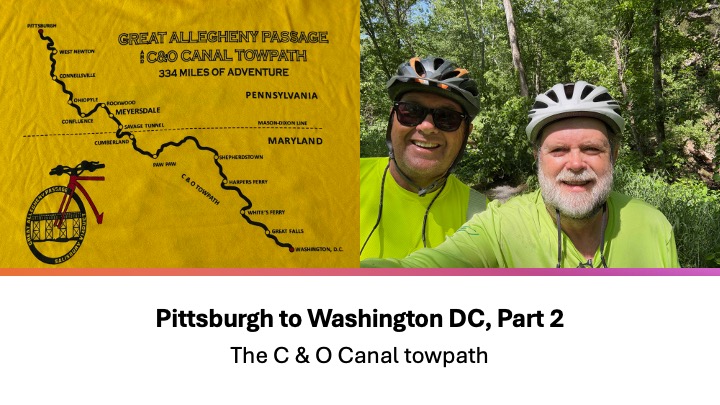

For Part 1, click here.

My brother becomes a hero

A couple of miles from the Paw Paw tunnel, we came around a bend and noticed bicycles thrown on the ground and several people kneeling over one of them. I peddled faster, thinking someone was hurt. When we pulled up, we saw Max and three women cyclists. No one was hurt, but one of the bikes had been taken apart. She’d had a flat. Max, seeing the stuff on the ground from the bike, said he threw up his hands and said, “there’s some engineers just behind me who can help.” At dinner the evening before, Max and Warren discussed various metals used in bicycles. From the discussion he learned my brother was a mechanical engineer. For some reason, he thought I was one, too. The women greeted us like saviors. When I shook my head at not being an engineer and pointed to my brother, they dropped interest in me and lauded praise on his arrival.

Warren to the rescue

We spent the next 30 minutes trying to get the bike back together. They had removed the entire back sockets and de-railer. While Warren and the woman with the broken bike worked finding what goes where, Max and I talked to the other women. They were all serious cyclists. When asked what they do when there’s a problem, they pointed to the woman whose bike was torn apart. “We call her husband. He’s a serious racer and knows everything about bikes and can walk us through what needs to happen.” Sadly, for them, we were in an area without cell service.

Once the bike was back together, we had the owner get on it and ride it a ways, making sure everything worked. It did. We ran into them again, late in the afternoon at the bicycle shop in Hancock. This was after 30 some miles of riding. One of the employees went through the bike and confirmed everything was back as it should be. The only issue was the tire pressure was a little low, but that’s to be expected with those emergency pumps which go on bicycles.

As they rode away, my brother joked about telling his wife how he had satisfied three women this morning.

Saturday, Cumberland to Hancock (61 miles of which we rode roughly 40)

This was to be the big day, 61 miles. The only problem was knowing there was a section of trail washed away in the floods about ten miles away. The National Park Service said there was no acceptable detour. We also learned from the bike shop that the road around this section was narrow, curvy, and unsafe to ride because of tractor trailers. So that morning, we arranged a shuttle for us and for Max, whom we’d talked to at breakfast. We had them drop us off at Paw Paw, cutting out about 25 miles of trail and the section that had been washed out.

Paw Paw Tunnel

The highlight of the day was the Paw Paw tunnel, an engineering marvel for the early 19th Century. We entered the tunnel just a mile or two from where the shuttle dropped us off. Bricks lined the walls of the tunnel. Bicycles (and mules in the day) travel on a wooden walkway that was so unleveled and bumpy we quickly heeded the warning to walk and not ride our bikes. Besides, the railing was only three foot tall, making it easy to tumble over if your bike fell. I attached the light to my handlebars and began the dark cool journey through the 3118-foot tunnel.

Little Orleans

The trail appeared better than we expected. While there were places with mud and many trees had fallen, requiring us to dismount and lift our bikes over them, it wasn’t as bad as some of the other places we’d heard of. We ate lunch at the Devil’s Alley Campground. When we came to Little Orleans, we left the trail and headed to Billy’s Place for ice cream. The place was a bar that served food. They advertised in large letters, “Beer, Boats, Bait.” In smaller letters the sign mentioned food, groceries, and shuttles. While we’d just had lunch, the burgers they’d fixed for a man and his wife we met outside of the establishment were enticing.

It didn’t take long this day before my left foot became sore. Over the past couple of days, the soreness would manifest itself late in the afternoon. The evening before I realized the area around the Achilles tendon had swelled. This slowed my pace and made me want to take more frequent stops, sometimes even walking my bicycle.

The Western Maryland Trail begins at Little Orleans. While this path parallels the C&O canal, it’s high above the river and is paved. This old rail bed, which we’d ridden on from Connellsville on the GAP, was a welcome relief to the mud of the C&O. It was nice to bel able to ride on pavement, even though we still had trees to pull over. We rode it all the way to Hancock, except for one detour for about a mile onto the C&O as there is a tunnel that hasn’t yet opened. About three miles outside of Hancock, we came upon a group of trail workers from the Maryland Parks clearing trees which had fallen during the recent storms.

Arriving back in Hancock

We arrived at Hancock at 5 PM, riding to the Presbyterian Church where I had left my car on Tuesday. We loaded our bikes and drove to Motel 8, where I had made reservations. On Monday night, I had stayed at the Potomac River Hotel, which looked like a bedbug haven. While it seemed to be free of bugs, the hotel had the ambiance of the 1940s. About half the lights were missing bulbs and the bathroom was small and the tub dirty. After discussing it, we decided to try the only other hotel in town. At least the bathroom was clean and larger, but the floors between the bed were soft and I wondered if one of us would fall through.

After cleaning up, we met Max at the Potomac River Grill, across from the hotel of the same name. The food was excellent, and the place crowed. It appears to be owned by the same folks at the hotel. At least they’re doing something right. I had a wonderful burger with a salad and a Stella beer.

After we got back to the hotel, Warren called his daughter, a physical therapist. She had me do a few moves and said she didn’t think my tendon was torn, but thought my tendon and muscles were angry and I may be suffering from Achilles tendinitis. She also recommended taking it easy, icing my ankle after walking or biking, taking ibuprofen for the swelling, and stretching in the morning. While riding, she suggested that while riding not to use toe-caps and to move my foot forward on the peddle so that I weight would be more on the arch of the foot.

Sunday morning, May 18

As Super 8s don’t provide breakfast, we drove to the IHOP on the east side of town, near the interstate. Coming back, I noticed some of the most creative line painting on a highway I’ve ever seen. Obviously, the Maryland line painters believe in drinking on the job!

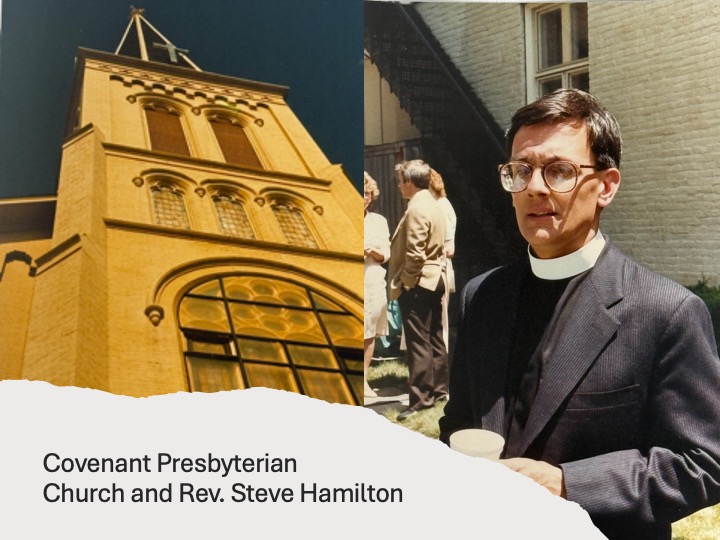

Then we worshipped with the good people at Hancock Presbyterian Church. I met Pastor Terry on Tuesday, when I left my car in the church’s parking lot. The 1845 sanctuary reminded me of the church where I was ordained as a Presbyterian minister, the United Church of Ellicottville in New York. Both brick sanctuaries featured high ceilings and a square design with cathedral style windows. While the United Church (formerly First Presbyterian) served as a stop on the Underground Railroad, the Hancock Church suffered damage during the Civil War when Stonewall Jackson’s men shelled the town.

This morning the service honored the church’s graduates and featured a musical trio (soloist, keyboard, and bass) from Fredrick called “Solid Ground.” They lead the congregation in singing and sang several songs themselves. Afterwards, the congregation had a wonderful potluck lunch which they do once a month. If you’re ever in Hancock on the potluck Sunday, don’t miss it!

Fort Frederick

Taking my niece’s advice, I decided not to ride on Sunday, which had been scheduled for our shortest day on the C&O, only 27 miles. Instead, I drove to Fort Frederick. The British governor had the rock-walled fort built during the French and Indian Wars to protect the frontier. In the American Revolutionary War, the fort housed British POWs. It never experienced the tragedy of a battle. Overtime, much of the fort had fell into disrepair, but the CCCs rebuilt it in the 1930s. Today, it’s a Maryland State Park. I toured the fort and reconnected with Warren as the C&O passes by the site of the fort. Then I moved on to Williamsport waterfront, where I waited to pick up Warren later in the afternoon. Williamsport features an aqueduct, where the canal (and its water) crossed a local creek, which was amazing to see.

That night, we stayed at a Hampton Inn in Hagerstown. For dinner, I had a pecan chicken salad and sausage chili at Bob Evans, which was across the street from the hotel.

Monday, May 19. A free day of touring the area

We had planned a day off, since I had a car in the area and was wanting to see the Antietam battlefield. Leaving early, we first drove to the nation’s first Washington Monument along South Mountain. This monument was built in 1827 by the people of Boonsboro, Maryland. In 1862, the people living in the valley used the site to watch the battle of South Mountain and Antietam. I first visited the monument in 1987, while hiking the Appalachian Trail. In our few minutes at the site, I met several section hikers on the trail.

After the Washington Monument, we headed to Point of the Rocks, to look at the C&O trail. We had seen Facebook posts of riders who became bogged in mud between Brunswick and Point of the Rocks and, talking with a bike shop owner, learned several had busted their de-railers by trying to ride through the muck. Then we drove along roads which parallel the trail, across from Harper’s Ferry and then across the Potomac to Shepherdstown, the oldest community in West Virginia. We had lunch in this quaint town at Marie’s Taqueria, where I had three delicious fish tacos.

Antietam

After lunch, we headed to the Antietam battlefield, first stopping at the visitor’s center to watch a movie introducing us to the battle and exploring the museum. September 17, 1862 is the bloodiest day in American history. While more died at Gettysburg, that battle lasted three full days. Lee had assembled his troops between the town of Sharpsburg (some still refer to the battle as Sharpsburg) and Antietam Creek. Fighting began that early that morning in a cornfield north of town. It continued in several different locations over the next twelve hours, before coming to an end. Strategically, the north won the battle. They forced the South to retreat into Virginia. But the price was heavy on both armies. The significantly larger northern army lost more soldiers than the south. Dinner for the evening was picked up at a grocery store that had a hot food and a large salad bar.

Tuesday, May 20 (36 miles)

With the reports of muddy and nearly impossible sections of the trail, we decided a new plan. We would start where we planned in Williamsport and ride as far east as possible before the mud became too deep. Leaving Williamsport, we peddled east. The two days’ rest made my ankle and Achilles feel better. I also stopped wearing my toe clips and moved my foot further up on my pedals. I wouldn’t have problems with my ankle until later in the afternoon.

As I was leaving Williamsport, I came up on a man walking his dog. “On your left,” I yelled, to warn him of my passing. He jumped, looked around at me, and started cussing me out. Here, I had tried to be polite and not scare him and instead, I both scared and upset him.

At first, our only challenge was stopping every little bit to pull our bikes over trees. This area is filled with history as we passed where Lee and his army were held up by a flooded Potomac as they retreated from Gettysburg, a year after Antietam. After about 7 miles, the path started to become muddier. After another half mile, we decided to turn around and head back to my car. On our way, just after we passed a huge down tree, in which we’d each be on a different side of the tree and hand bikes over, we met a park service crew cutting fallen trees. The last half of the ride back to my car was much easier.

Afternoon ride

Then we headed to Brunswick. We had hoped to peddle here today, but knowing there were sections of the trail out, we set out and road east to Point of the Rocks, stopping for lunch on the trail about halfway to our destination. Our thoughts were that this would give us only 48 miles to Washington on Wednesday. I appreciated seeing this site in the afternoon. The day before, still early in the morning, had the sun behind the unique train station.

Point of Rocks

The original Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) tracks tracks ended at Point of Rocks, Maryland . Here, the railroad and the canal locked in legal wrangling over right away. It was eventually settled, with the railroad building a tunnel, which allowed them to move the lines westward. The railroad also began building a line eastward, to serve Washington DC. In the 1870s, where the two tracks converged, forming a wye, they built a station. Today, the station closed and owned and used by railroad. The Maryland commuter rail that runs into DC boards just west of the old station.

I waited to catch a photo of the station with a train that was slowly approaching. The train was going slow and I could have easily jumped aboard as a hobo, but then I noticed that this unit train on open containers marked with the symbol of Republic Trash Service. Dirty water poured from the containers and a rotten smell filled the air. The stench encouraged me not to take up hoboing.

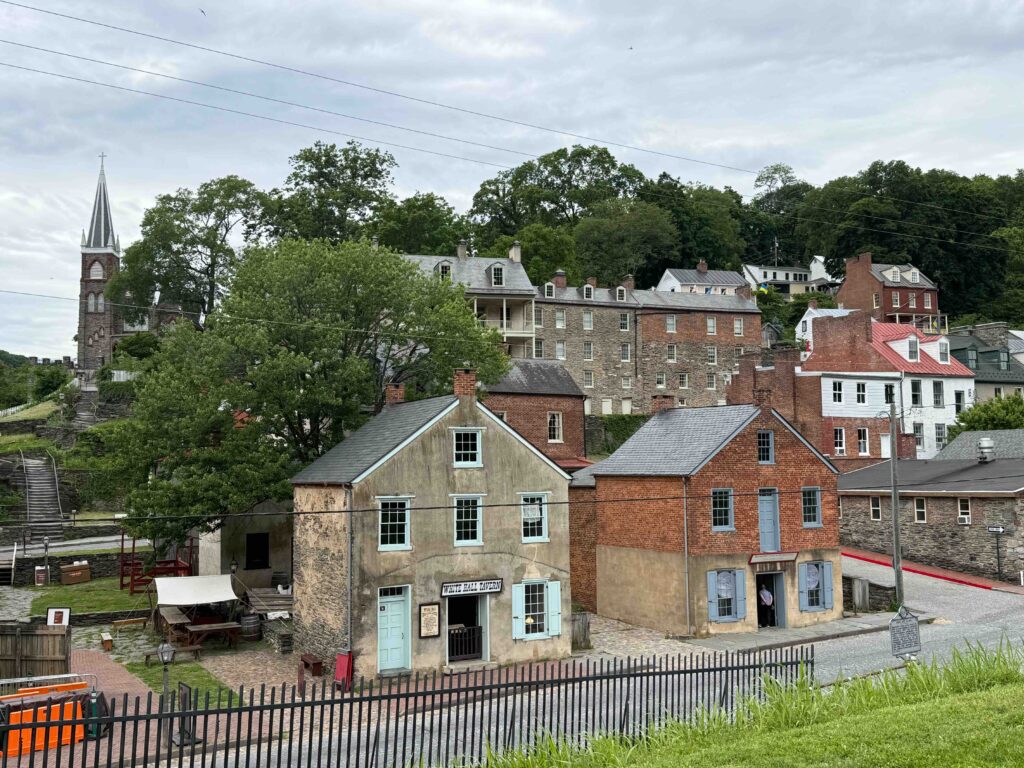

Harpers Ferry

After riding back to Brunswick, we continued west on the trail to Harpers Ferry. This also washed out but was temporarily patched with gravel. In 1987, the afternoon before visiting the Washington Monument, I had hiked along part of this section who also serves as the Appalachian Trail. Across from Harper’s Ferry, we locked our bikes up and walked across a pedestrian bridge. My Achilles ached and I mostly hobbled along. We explored a little of the Lower part of Harpers Ferry. Then we rode back to my car, loaded up our bikes and headed to our hotel, where I could ice my ankle. With only two hotel options in Brunswick and no B&B available, Warren had booked us in the closest hotel to the trail, a Travelodge, 1.7 miles away from the C&O. To reach this hotel on bicycles required a hard climb (as did the other hotel which was further away).

Hotel in Brunswick

We feared the hotel might be a repeat of the Super 8 night, but it was quite nice. It seemed odd to have a hotel like this off a major road or interstate, but we quickly surmised the hotel primarily customer to be the railroad. They even had a lounge only for CSX employees and featured a 1950s style dinner that was open 24 hours a day. A local taxi company shuttled train crews back and forth to the railroad.

A great ending dinner

That evening, we decided to forgo the diner and try the Potomac Street Grill near the railroad tracks. They advertised both American and Middle Eastern dishes. It was a good decision. I had a delicious combo shawarma platter, with both chicken and lamb, a wonderful mediterranean salad, and a local beer for $24.

Wednesday, May 21, 2025 zero miles on bike/350 in the car

The night before, we watched the news and weather channels for what the next day would bring. Everyone was saying 100% chance of rain, with rains heavy in the morning and again later in the afternoon. It poured as we walked over to the diner for breakfast. We decided to quit. Having already had gaps in our travels along the C&O, we could come back and do the C&O again. Besides, my Achilles hurt.

Our plan had been to ride into DC, stay with my brother’s sister and brother-in-law, then the next day, Warren would bring me back to my car and we’d head home. Now, we’d both be home a day early.

We left Brunswick at nine, in the pouring rain, hoping to miss the worse of the traffic. As we approached DC, the rain slowed to a drizzle. We stopped at Great Falls to witness the power of the Potomac at high water levels. Amazing rapids! A few minutes after leaving the rapids, we arrived at Hitch’s home, where we transferred my brother’s bike to his car. A few minutes later, we took off on our separate paths. For me, it rained most of the way home.

Ankle Update

I was checked out on Tuesday. While I didn’t tear any tendons, I have angered a few. The recommendation is that I not do any bike riding or long walks for a few weeks while it heals. In addition, I will do a few weeks of physical therapy to strengthen the muscles in my ankles.