I am going to do something different and post an old article from a peer review journal. I became interested in A. B. Earle and his west coast revivals while I was writing my dissertation. Afterwards, I spent much time searching out sources of his travels to complete this narrative This involved spending lots of time looking at microfilm of old newspapers. The article was published in the American Baptist Quarterly, volume XXV, #3 (Fall 2006). I apologize for the length of the article. Save yourself some time and skip the footnotes!

Bringing in Sheaves: The Western Revivals of the Reverend A. B. Earle, 1866-1867 Charles Jeffrey Garrison

“Away with it! Away with him! Away with the evidence!” Over and over, the Reverend A. B. Earle slightly changed the phrase to emphasize Jesus’ continual rejection by the Pharisees. Each story recalled accentuated the danger of not accepting Christ, the implication being that those who rejected him had lost their chance at salvation. Basing his sermon titled “The Unpardonable Sin” on Matthew 12:32, Earle described the sin as continually saying “‘no, no, no’ to the offers of mercy until you are a sinner let alone or given up by the Holy Spirit.”

In setting out his argument, Earle asked and answered four questions:

- What is the unpardonable sin?

- Who commits the unpardonable sin?

- How does this sin show itself after it has been committed?

- Why can this sin not be forgiven?

This sermon encouraged his listeners to act, not wait, for there is an eternal urgency for them to accept Christ as their Savior. After making his case, Earle draws the sermon to close, telling a story from the Civil War the nation had recently experienced, emotionally tugging upon the hearts of his listeners.

According to the story, a soldier had a wound that required a surgeon to amputate a limb near the joint where it attached to the torso. It appeared the surgery had gone well, but then he began bleeding. The surgeon was called over and he found the open vein and sewed it up stopping the bleeding. This happens several times. Earle, a good storyteller, provided detail to build suspense. After having stopped the blood on several occasions, blood then began to flow even more freely. A nurse, placing his thumb over a large artery, called again for the surgeon. This time, the surgeon discovered he couldn’t sew up the vein without the nurse removing his thumb. The artery was so large if the thumb was removed, the soldier would die immediately. The soldier was given the news and arrangements made for him to prepare for death. He dictated letters to loved ones and made arrangements for his death. When he was done, he thanked the nurse and told him he could remove his thumb. The nurse then faced a severe trial for he knew he could not go on holding the artery forever, but also knew that as soon as he removed his thumb, the man would quickly bleed to death.

“I think I feel very much as this nurse did,” Earle told those gathered, “fearing, as I do, that with many in this congregation the crisis has come when you are to decide where you will spend eternity.” Then after a few more remarks, he asked those who intend to serve God to rise. Earle preached this sermon throughout his revivals on the West Coast during 1866 and 1867 and credited it with bringing “no less than five thousand souls… to embrace Christ.” [1]

For nine months during 1866 and 1867, the Pacific Coast of the United States buzzed with excitement about the Reverend A. B. Earle, a popular preacher from the East. During this time, Earle traveled up and down the coast, from San Francisco to Portland and inland into the mining districts, leading revivals. Because many of those in the West had roots in New England and New York, they were familiar with revivalism and turned out in large numbers to hear this celebrated preacher. This paper examines the work of the Reverend A. B. Earle in the American West in the years following the Civil War. During this time he was one of the two most popular evangelists in the United States, the other being William Boardman.[2]

In order to understand Earle’s revival methods, one must first have an understanding of the context with which he worked and from which he came. First, this paper will review the role revivalism played in the Northeastern United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Then, it will review Earle’s life and ministry prior to accepting the invitation to preach throughout the West. Next, it will discuss Earle’s work in the American West, looking at both where he labored as well as the style of his revivals. Finally, the paper will examine impact of Earle’s revivals.

The Context of Revivalism in American

Shortly after the turn of the nineteenth century, America entered a second period of intense revivalism. Starting on the frontier, with a rural communion meeting in Bourbon County, Kentucky, these revivals spread throughout the young nation.[3] On the frontier, these revivals helped bring a new generation, one that had moved away from the established churches in the East, back into the fold. But the frontier genesis of the Second Great Awakening quickly shifted to the cities under the leadership of evangelists such as Charles Grandison Finney. Instead of bringing religion to settlers who had moved away from organized churches, Finney brought religion to individuals living in the shadows of church steeples. Finney and others like him adopted several new techniques to cultivate the revivals and ensure their success. In advance of his revivals, Finney organized prayer meetings to prepare the hearts of those involved. He also employed every available means to advertise the meetings. The printed word excited the young nation and Finney printed handbills and posters as well as utilizing newspapers to his advantage. Finney also arranged for special music which drew crowds, held special services for women who were allowed more freedom in his meetings, scheduled them when most people were free to attend, cultivated lay leadership and worked across denominational lines. Converts from Finney’s revivals provided leadership for Abolitionism and other reform movements, even though Finney himself did not support legislating morals. Instead, he focused on evangelizing individuals in the hope conversions would lead to a change of heart and behavior that would eventually transform a nation.[4]

In the aftermath of the Second Great Awakening, America witnessed an explosion of lay-led, religious-based organizations focusing on single issues such as Abolition, temperance, labor reform and Sunday School promotion. Even though the excitement of the Second Great Awakening ebbed during the mid-1830s, these groups flourished, bringing religion into the public sphere. [5]

The next major nationwide revival began in the September 1857 when Jeremiah Calvin Lanphier, a former businessman and lay leader in the New York City’s Fulton Street Dutch Reformed Church began holding prayer services at lunchtime for businessmen in the financial district of the city.[6] The telegraph and newspapers spread the excitement throughout the nation. This “national Pentecost,” as Timothy Smith called the revival, led many to hope that an “America baptized in the Holy Spirit” could “destroy the evils of slavery, poverty and greed.”[7] Although Smith may overstate the goals of the revival, it impacted the entire nation, with a number of its converts playing a major role in the nation’s religious history for the next half century.[8]

The revival that began in 1857 marks several shifts in American religious history. While earlier revivals provided opportunities for women to participate, the mid-century revivals began during a resurgence of masculine Christianity. At his first businessmen prayer meeting, Lanphier asked a woman to leave because he felt her attendance would discourage men from attending. However, as with the earlier revivals, women soon played a role, and church membership statistics for the period indicate that more women than men made a formal commitment to join a congregation.[9] The mid-century revivals were known for their civility. Order was a primary concern in these revivals and revivalists were proud of the business-like attitude of the services. Of course, this does not mean that feelings or emotions played no role in the revivals. Prayer, testimony and hymns, which had gained popularity in churches during the first half of the nineteenth century, were all employed to set the stage for conversions. [10]

One major difference in the revivals of the late 1850s, when compared to earlier revivals, is the lack of a groundswell of ethical concerns following the revival. Converts from earlier revivals provided volunteers for the “benevolent empire.” The only volunteer association to come into national prominence following the 1857-58 revivals was the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), which had been imported from England in 1851. Kathryn Teresa Long’s in-depth study of the revival found no other social or ethical impact from the revival. Instead, she discovered evidence to the contrary, that revival leaders sought to privatize religion and avoided topics such as slavery that might offend businessmen with interest in the South.[11] Supporting Long’s thesis that the revival encouraged a conservative and privatized faith, Sandra Sizer’s study suggests that the conservative and businesslike pre-Civil War revivals were a forerunner to Moody’s revivals later in the century.

Even though the revivals of 1857-58 were more businesslike than the Second Great Awakening, there were also more radical shifts taking place in American religion during this same era. Perfectionism, or the second blessing as it was commonly called, played a limited role in these revivals.[12] This radically Arminian concept maintained that one could, through prayer, overcome sinfulness and thereby obtain a perfect state while on Earth. The doctrine was a precursor to the holiness movements that would occur toward the end of the century. The Reverend A. B. Earle, during this period, began to seek a “second blessing” or, as he called it, “the rest of faith.” He would experience this “rest,” according to his autobiography, at Cape Cod, on November 2, 1863 at 5 P.M. Earle refused to call this a “sinless perfection,” preferring to describe it as a “rest of faith” in the “fullness of Christ’s love.”[13] From available sermons, it appears he downplayed this experience in his evangelistic preaching. Even though Earle considered this an important experience for himself, he never made it an issue in his preaching which allowed him to work with a variety of denominations, including those that eschewed such beliefs.[14]

Revivals in California

As historian Kevin Starr notes, during the first year of the Gold Rush, almost half of the ships anchoring in San Francisco Bay were from New England ports. These ships contained men who had grown up with revivalism, some of whom shared New England’s messianic hope to be the “founding race” of California. Joseph Augustine Benton, a graduate of Yale and founder of First Church Sacramento, in his Thanksgiving sermon of 1850, visualized California in the same way his Puritan ancestors saw New England. California, with all its abundance, was to be “America’s City on a Hill by whose example the Orient would be brought to Christ.”[15] A common assumption among early religious leaders was that gold in California had been hidden by God until the region was firmly in the hands of the United States so that the state’s wealth could bless America.[16] However, even with such an optimistic outlook, the clergy who came to California during the state’s early years found themselves with an impossible task. Although churches in cities like San Francisco and Sacramento flourished, there were still large sections of the population shunning organized religion. But religious leaders continually tried to “civilize” California, which included bringing one of their own, the Reverend A. B. Earle, to lead the first concentrated set of revivals throughout the region.

Some religious leaders on the West Coast understood the challenges they faced in California. An 1865 editorial in The Pacific, a religious newspaper published in San Francisco,[17] called for a new type of evangelism for California. The editorial compared attempts to build permanent churches in mining camps to that of building a church for Mississippi raftmen along the banks of the river. Neither were stable communities. The editorialist went on to encourage all denominations to work together for the common goal of evangelizing the Pacific Coast and to avoid competition which wasted resources. Often, several denominations strove to build the first church in a town, a policy that often resulted in a surplus of churches once the initial mining boom was over. The Pacific, aware that the challenges they faced in the West were complicated by efforts of the Eastern denominations to rebuild churches destroyed in the South during the Civil War, called for unity in establishing a Western theological seminary to educate clergy for the West Coast. Furthermore, the newspaper called for a unified revivalistic campaign, a “new Great Awakening,” that would strengthen California’s churches as earlier awakenings strengthened the church in the East.[18]

Revivals and revivalistic preaching were not unheard of in California. During the early days of the Gold Rush, Methodist pastor and revivalist William Taylor conducted a street preaching campaign in San Francisco. Taylor would return to the East where he played a role in the 1857-58 revivals. Like the circuit riders in the Eastern Frontier, Taylor traveled throughout the state preaching wherever he could find an audience, from saloons to wharves, and ministering to those in need. Taylor was especially noted for his work in hospitals. From 1848 to 1856, Taylor worked in California, impressing those who heard him.[19] The Awakening of 1858-59, which rocked the rest of the nation and especially the Northeast, was felt to a lesser degree, in California.[20] In 1859, the brother of Charles Finney moved to California. Although not a revivalist like Charles, George Finney spent his time organizing new Congregational Churches and promoting temperance.[21] In the 1860s, Protestant Churches in many communities, heeding the call by the Evangelical Alliance, joined together for a week of evening prayer services each January.[22] Many revivals were felt locally such as the one at the Methodist Church in Santa Clara in 1863 when more than a hundred joined the church.[23] The mining community of Columbia, California experienced a period of revival arising from the 1866 New Year’s prayer services.[24]

California did not experience the horrors of the Civil War, but like the rest of the nation, they were relieved at the war’s conclusion. Many saw the war as an “Apocalyptic contest.” Those on the Northern side identified their cause with the establishment of the Kingdom of God. At the end of the war, there was great hope the evangelical cause would continue to advance.[25] Although there were Southern sympathizers in California, the state was strongly Union and mourned the death of President Abraham Lincoln. In California, as with the rest of the country, memorial services were held in honor of the slain president who was revered for holding the union together and removing the stigma of slavery from the nation.[26] The optimism at the war’s end and the recent religious interest demonstrated during the Lincoln memorial services set the stage for the revival.

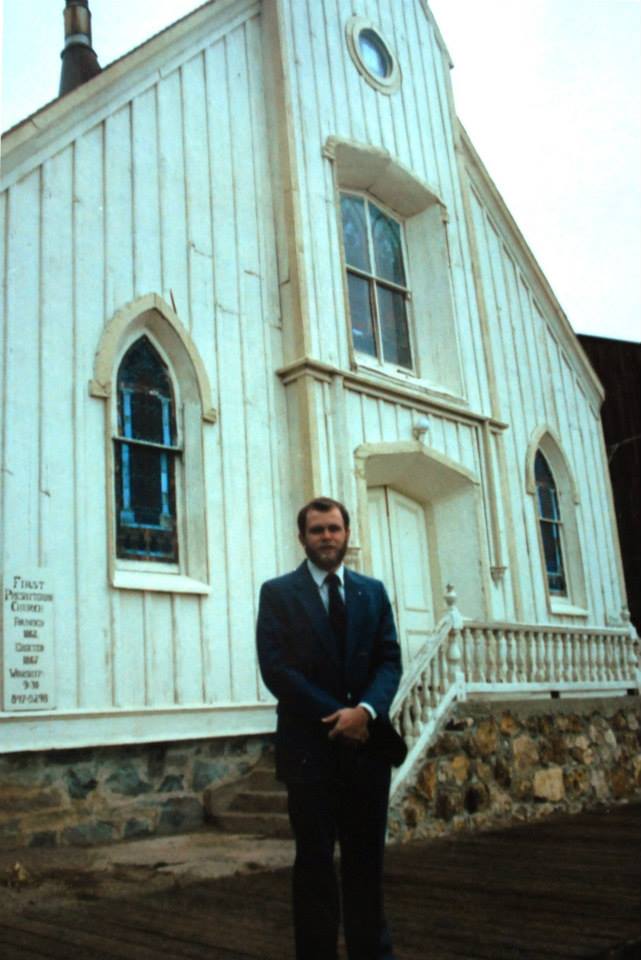

The first concentrated attempt at a unified revival in California by the Protestant Churches occurred shortly after the Civil War when, in July 1866, the San Francisco Ministerial Union invited the Reverend Absalom B. Earle to labor on the Pacific Coast. The Ministerial Union selected another nationally known evangelist, the Rev. E. P. Hammond, known as a children’s evangelist, as their second choice.[27] In preparation for the expected arrival of a well-known revivalist, ministers were encouraged to preach repentance. The Ministerial Union also instituted a daily inter-denominational prayer meeting held at Calvary Presbyterian Church during the noon hour, obviously borrowing on the success of such meetings during the 1857-58 revivals. On August 30, 1866, The Pacific reported that Reverend Earle had accepted the invitation and noted his plans to visit San Francisco.[28] Earle believed “that Christians of every name should work together” for the “Redeemer’s cause.”[29] His emphasis on “union revivals” was what the ministerial society hoped to see on the West Coast.

A. B. Earle

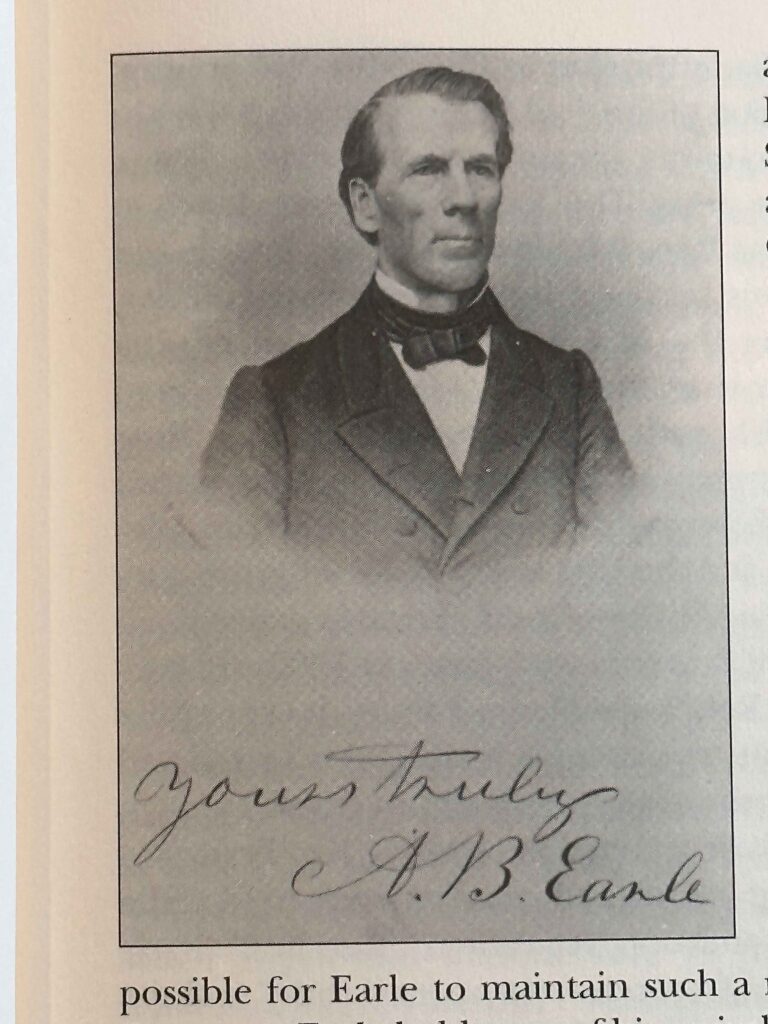

Absalom B. Earle was born in Charleston, New York. On November 13, 1830, at the age of 18, he preached his first sermon in the small upstate town of Truxton. His text was Matthew 28:20, “Lo, I am with you always.” Two yoked Baptist Churches soon called him as their pastor. Later, Earle would develop an evangelistic talent and leave the pastorate for what became known as the sawdust trail. Following Finney’s example, Earle devoted his work to “union revivals.” By his own admission, after 50 years of ministry, he had conducted over 800 series of revival meetings representing twenty-two denominations.[30] In addition, Earle wrote an autobiography and a spiritual autobiography as well as a collection of devotions for individual and family worship and edited a revival hymnal.[31]

Earle’s preaching style was generally praised for his lack of sensationalism, but Earle had a stock of stories designed to tug at the hearts of his listeners. In his autobiography, Earle devoted a chapter to two such “incidents.” Both cases involved a young girl who died. The first story is about a girl dying, but who hung on to life until her mother promised to accept Jesus as her Savior. The girl then died in peace and was with her Lord while her mother worked on her father’s soul. In the second story, the daughter of a skeptic had died. The broken father could only say as they closed the casket, “I’ll never hear her call me father again.” After the service, Earle told the man that he wasn’t so sure that he wouldn’t hear her call him again, that she was now “walking those ‘golden streets,’ and perhaps is this moment saying, ‘I wish my dear father was up here—it is so beautiful.’” After some thought, he proclaimed his intention to “seek Jesus.” According to Earle, the man later set out “preaching the glorious gospel of the blessed God; and little Josephine, who is waiting ‘across the river,’ may again call him ‘father.’”[32]

Like other revivalists, Earle utilized music to set the stage for the revivals, urging anyone interested in promoting revivals to “have the best singing you can in all your meetings.” In a sermon titled “Faith,” Earle referred to 2 Chronicles 20:21-22 and reminded his hearers that “one of the greatest victories ever won by Jehoshaphat was won by singing.” He further noted that “God blessed his people when they sung his praises.”[33] After a lull in the first two decades of the nineteenth century, hymn writing revived in the 1820s and continued to increase as the decades passed. With time, hymns became more passionate. Like the later revivals of Moody and Sankey, Earle published his own collection of revival hymns in 1865 which he used to reinforce his revival efforts. [34]

Earle on the Pacific Slope

Earle’s leadership of revivals in California, Oregon and Nevada are documented in his own autobiography, Bringing in Sheaves, as well through on-going reports in the religious newspaper The Pacific. Although these sources are not a critical account of Earle’s revivals, and report on the activities of Earle only with glowing terms, they provide a framework for understanding the scope of his work. Additional accounts of the revivals can be found in local newspapers, especially during the time of his revivals. In recreating the following story, the author of this paper draws from all three sources.

Earle and his wife left New York City on September 11, 1866. The night before their departure, a prayer service for safe travels and success was held at Strong Place Church in Brooklyn. The Earle’s arrived in San Francisco in early October and he immediately began to preach in churches throughout the city.[35] The first Sunday afternoon he preached at the Stone Church (Congregational). On Monday afternoon and evening he preached at the Presbyterian Church on Howard Street and Tuesday afternoon and evening at First Baptist Church. According to Earle, “the harvest had already commenced,” upon his arrival in the city.[36] Mid-day prayer meetings had been on-going since July in anticipation of his arrival.

Earle spent five weeks in San Francisco preaching twice a day and three times on Sunday. The luxury of preaching the same series of sermons over and over again allowed him to enter the pulpit nearly 20,000 occasions in fifty years of ministry.[37] Such practice, without regular pastoral responsibilities, made it possible for Earle to maintain such a rigorous schedule. While in San Francisco, Earle held most of his revival meetings in Pratt Hall, although a few services were held in Union Hall. It was decided to rent these facilities, at a cost of $15,000, since they had a larger capacity than any church in the city. Services were generally held at 3 and 7:30 P.M.[38]

In addition to his regular preaching, Earle conducted special Saturday afternoon meetings for children. These were held in various churches around the city in order to allow more children to attend. In one such service, held at First Congregational Church, 200 youth expressed their “desire to become children of God,” and a number of children from the Blind Asylum said they wanted to “see Jesus.”[39]

One of the leading San Francisco newspapers, Alta California, reported, in the middle of Earle’s work in the city, a revival, “such as has never before been experienced on this coast, is now in process.” The detail in which Earle covers the revivals in San Francisco and others throughout the West in his autobiography indicates the success he felt while laboring in the region. [40] Earle closed his work in San Francisco on November 11, 1866. On that day, he preached at Pratt’s Hall at 3 P.M. and at Union Hall at 7:30 P.M. After his departure, the daily noon prayer meetings continued. Although the attendance was lower, the spirit of the meetings had greatly improved, according to reports. [41]

After leaving San Francisco, Earle traveled to Columbia and Sonora, sister towns in the southern portion of the gold mining region. For eight days Earle preached in these two towns, spending the afternoon in one community and the night at the other. This was his first experience in the mining camps and Earle was favorably impressed. He had feared miners would be apathetic to his message, but to his surprise discovered a religious hunger among the miners.[42] Although the mining industry played an important role in these two towns, the boom had already past and a more stable society had emerged. In the three years before Earle’s visit, the community of Columbia had enjoyed two periods of revival. In 1864, the Reverend William Mulford Martin, pastor of the Presbyterian Church, led the first revival following the construction of a new church building.[43] The second revival began with all churches celebrating the Week of Prayer in early January 1866 and continued through late March. The Rev. David Henry Palmer, pastor of the Presbyterian Church, had been instrumental in leading this revival and had left Columbia for New York shortly before Earle’s arrival. [44]

After Columbia and Sonora, Earle traveled back to the San Francisco Bay and spent ten days preaching in Oakland. Services were held at the Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist and Congregational Churches.[45] Earle later reported that the “windows of heaven were opened wide,” and the revival was especially successful among school students. The Pacific’saccount of this revival supports Earle, noting most of the large numbers of people indicating their desire to become a Christian were young.[46]

Next on Earle’s itinerary was Stockton, California, a city situated on the banks of the San Joaquin River. A physician and a leading citizen of the community there who had, according to Earle, “long been an infidel,” was moved by the “love between the denominations” and converted. He renounced his former beliefs and appealed to others who didn’t believe to embrace Christ.[47] Afterwards, Earle headed north to California’s capital, Sacramento, where he described “the spiritual rain” as “more abundant and powerful than the natural.” The winter rainy season had begun, discouraging travel from outlying areas. Although the weather was an obstacle, the revival was successful enough for Earle to extend his stay in the capital city for an additional week.[48] As in other communities, the four main established churches—Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian and Congregational—worked in harmony. In all, he labored twenty days in the city, closing the revival on the sixth of January.[49]

After Sacramento, Earle traveled west to the town of Petaluma, where he preached to overflowing crowds at Hinshaw’s Hall, the largest facility in the city.[50] During part of the revival, a traveling theater group had rented the hall and the revival services were moved into a local church. However, after the first night, in which only eight people attended the play, the theater postponed the show. According to Earle’s autobiography and the local newspaper, the revivals were successful with many prominent citizens converting and dedicating themselves to the Christian life. Included in the list of converts were the Honorable J.B. Southard, Judge of the Seventh Judicial District, and two actors of the traveling theater companies whose performances had been postponed. Following the revival, 120 persons united with the three churches involved.[51]

Late in his life, the Rev. William Pond, pastor of the Congregational Church in Petaluma, recalled Earle’s revivals and gave a contrasting opinion as to their success. According to Pond, only a few of those who joined the three churches remained “staunch” in their faith. The Methodist minister confessed to him, three months after the revival, that all his “converts” had fallen away. During this same time, the Baptist congregation had dismissed their pastor and in its aftermath declined in strength. Seeing no long term results, Pond said he “believed most heartily in evangelistic effort, but not of that sort in which hypnotism masquerades as the very Spirit of God.”[52] Most reports of Earle’s ministry were positive; however, as we will later see, William Pond was not his only critic.

Following Petaluma, Earle traveled south, by steamboat and railroad, to San Jose. During his travels, a fellow passenger discouraged him, saying that the smallest church in San Jose would be large enough for the all the people interested in attending a revival. Rejoicing afterwards, he noted that soon no church in the city could accommodate the crowds.[53] The revival began on the 23rd of January in the Methodist Episcopal Church and after six days moved to the Presbyterian Church. In the thirteen days Earle ministered in the city, he recorded the names of 250 who participated in “the joy of salvation, either new or restored, during the meetings.” All churches set aside Tuesday, January 29th as a day of fasting and prayer. Even the public schools closed. [54] In his autobiography, Earle relates many incidents of conversion, but also tells of one man who rejected the call of Christ in San Jose. The man was an innkeeper and felt he couldn’t convert because he would have to close his bar and would, thereby, deprive his family of support. However, Earle noted another innkeeper who answered the call and closed down his bar that same evening. While in San Jose, Earle was reunited with old friends from New York who were also converted. On another occasion, while working in San Jose, a teacher who denied the divinity of Christ came to his room and the two spoke about his beliefs. The man left, unconvinced, but promising that he would not “grieve the Spirit by disobeying his voice.” Earle noted that the man felt safe in making such a promise and, in three days, rose at a meeting and admitted his sinfulness and his need for an “Almighty Savior.” A few days later, full of confidence in Christ, he spoke before a meeting. One of the fruits of the San Jose revival came after Earle had returned to the East. A Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) was established and Earle was made an honorary member. Following the revivals, the First Presbyterian Church in San Jose received sixty-eight new members.[55]

Santa Clara, a city a few miles west of San Jose, was Earle’s next stop. He preached seven days in the city. As had become his custom, a day of fasting and prayer was observed. All the meetings were held in the Methodist Church although at one meeting it was noted there were twenty-four ministers present from seven different denominations, some having traveled forty to sixty miles to hear the Reverend Earle. The Pacific noted that approximately 150 signed his “register” as “recipients of grace,” while Earle reported 200 unconverted men, women and children rose in this last meeting asking for prayers.[56]

After Santa Clara, Earle moved inland to the Marysville, a city founded at the junction of the Feather and Yuba Rivers. The rainy season continued and the city, a hub for mining activity, probably had more miners present due to the difficulty of work “diggings.” Though the city was thought to have been hostile to religion, several churches started the revival before Earle’s arrival on Saturday, February 16. That evening Earle preached the first of his sermons at the Presbyterian Church where most of the union meetings in Maryville were held. Wednesday, February 20th, was set aside as a day of prayer and many businesses closed for the services. The meetings were often crowded, at times so much so that those wanting to go forward were unable to make their ways down the aisles. Earle planned to spend just a week in Marysville, and then move on to Carson City, Nevada, but was persuaded to stay longer. He agreed to stay another week provided the people of Marysville would “devote the week to Christ.” In all, he labored in the city for 17 days.[57] On Sunday evening, March 4th, he preached “The Unpardonable Sin” sermon, one that was becoming famous on the West Coast, at the Marysville Theater. An estimated 1200 people crowded into the theater to hear him. The gallery was packed. Some left fearing it might collapse under such weight.[58] It was reported that 350 people in Marysville were converted under Earle’s preaching and that a total of 240 had united with the Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and Episcopal Churches.[59]

In a rather detailed article on the revival, in the Marysville Daily Appeal, the editor credited Earle’s success to the laying aside of political and sectarian differences and his ability to unite various churches and minister toward a common goal. It was noted that ministers and laymen who had never met in religious worship had been united and, “if they allow the ‘old Adam’ to revive in their hearts, will never again meet for such purposes.” A correspondent confessed he attended Earle’s revivals not because of his eloquence or captivating gifts, but because he was sincere, earnest, and is “happy and wishes others to be happy.”[60]

Earle was not a hell-fired preacher. In one of his published sermons, “Joy Restored,” based on Psalm 51:12, “Restore unto me the joy of thy salvation,” Earle tells about an incident early in his ministry in which he preached a series of five sermons to two congregations in New York State. “The fifth was prepared with a scorpion in the lash; it was a severe one, and the last harsh sermon I have preached,” Earle noted. After the sermon, which he describes as powerless, Earle and one of the ministers united in prayer, admitting that their hearts were not filled with love. Then, Earle returned to the pulpit and preached a sermon with “no lash, nothing harsh about it,” and witnessed the congregation break down and confess and commit themselves to the work of revival.[61] Even though this sermon was about the duty of every Christians to enjoy Christ love, Earle’s message had revivalistic overtones. “[W]hen a Christian carries about a sad, dejected countenance, he misrepresents religion,” Earle argued. Further, he noted, when a church becomes cold, it will “never do her duty to her members, nor take care of young converts.”[62]

Leaving Marysville behind, Earle changed his plans. Instead of going to Nevada, he headed to Placerville where he began the revival in the Presbyterian Church. It was said that the church was “filled with people more curious to see and hear him than from any immediate concern for their eternal welfare.” When the invitation was issued at the end of one meeting, many wives came forward to request prayers for their husbands.[63] A pastor from Placerville wrote Earle saying, “The people of our city will feel under a lasting obligation to you, and will, at least during the present generation, keep your memory green.”[64]

Earle left Placerville for Oregon, accepting the invitation from ministers and businessmen of Oregon to come before Spring when the mining population would scatter throughout the countryside. In mid-March, Earle boarded the Steamer Ajax for Portland. Methodist Episcopal congregations in the upper Willamette Valley had recently experienced a revival although there is no indication these revivals were connected to Earle’s “Union Revivals,” that followed. On the trip to Oregon, the steamer stopped at Astoria, located at the mouth of the Columbia River, to pick up firewood and water. A local man, who had been ministering in absence of an ordained minister, came aboard the ship and requested Earle to preach for there were no ministers within 100 miles. Earle obliged and preached in a local hall while the ship was refueled.[65]

According to a letter from the Congregational, Methodist and Baptist pastors of Portland, which appeared in the Pacific Christian Advocate, Earle spent approximately three weeks in Oregon. Most of his work was to be done in Salem and Portland with two days set aside for Oregon City. These pastors called on all to attend his meetings.[66] As elsewhere, Earle’s work in Portland stirred interest in religion. The Oregonian, a Portland newspaper, reported: “It is remarkable that, go where you will, on the street, into business houses, down upon the wharf, among families, everywhere, the subject of ‘Rev. Mr. Earle’ and the revival meetings is sure to be broached and discussed. The talk is not confined to church-going people.”[67] Evening services were held in the Presbyterian Church and were so crowded that many in attendance had to stand. At one service, the opportunity for individuals to give their testimony was presented and over 200 people spoke. On Sunday, the meetings moved to the Courthouse. In Salem, the state capital, Governor Woods used his office to encourage the revivals and it was said that people traveled up to forty miles to hear the Rev. Earle. The meetings in Salem were held in the University Chapel. It was the largest room in town, but insufficient to hold all who wanted to hear Earle.[68]

Leaving Oregon behind, Earle took a steamer south to San Francisco and then traveled inland, across the Sierra Nevada, to the Comstock, the great mining center in the young state of Nevada. The Rev. William Mulford Martin, formerly the pastor of the Presbyterian Church in Columbia and now pastor in Virginia City, had invited Earle to Nevada.[69] Earle was already known in the Silver State from reports of his preaching throughout the California mining camps. A week before his arrival, the Territorial Enterprise, a leading newspaper in Virginia City, reported;

Rev. Mr. Earle—This talented gentleman, of whose eloquence we have heard so much, is expected to arrive here this week from Oregon, in case the steamers make their trip in the usual time. He will meet with a hearty welcome in the city. On Monday afternoon the ministers of Virginia and Gold Hill will meet at the residence of Rev. Mr. Martin, #75 South B. Street, at 2 o’clock, for the purpose of making arrangements in regard to the time of holding services in the various churches.[70]

The revival began in the Presbyterian Church on Sunday morning, May 5, 1867. Alf Doten, editor of the Gold Hill News, attended the meeting and made the following observations about Earle in his journal:

About 60, tall, good appearance—hair mostly gray—earnest and impressive manner—common & not flowery, but truthful language—familiar & common style of similes—Appeals to home feelings & proclivities of hearers—none of your ranting sensational revivalist—Calculated to lead all who are in darkness to truth and light.[71]

Earle’s revivals in Virginia City continued through May 23rd. For the first week, he preached in the new Presbyterian Church on “C” Street. The services were moved during the second week to the Methodist Episcopal Church at the corner of “D” and Taylor Street. The final week of services was held back in the Presbyterian Church. The climax of the revival came during the second week at the Methodist Episcopal Church when Earle preached the “Unpardonable Sin” sermon to an overcrowded church. Reporting on the meeting, The Trespass, a Virginia City newspaper wrote:

[N]o effort for excitement, no strange, startling statements; but the simple, conclusive setting forth of the subject brought the whole mass, almost without an exception, to their feet, a most solemn testimony of a fixed purpose to cherish the interest each felt in his personal salvation.[72]

Alf Doten, who had earlier expressed approval of Earle’s style of preaching, was critical of the “Unpardonable Sin” sermon. In his journals, Doten wrote:

This [the unpardonable sin] he makes out to be people not coming forward & becoming converts to his, Earle’s, teaching and “accepting Christ”—All who “reject Christ” he says cannot be pardoned by God & will consequently go to hell—In view of the fact he has thus far made not two hundred converts in this City out of a population of 10,000, it would seem that an extremely small proportion have any chance of getting into heaven—His views on the subject are decidedly limited.[73]

Doten again attacked Earle in a letter, writing:

The Rev. A. B. Earle’s revival conquest of the West [was] somewhat checked by the common sense of Virginia City, which finds it hard to believe that only Christians can enter Heaven and still harder to believe that the only way to Christ is through Earle.[74]

Four days later, Dote notes in his journal that the Presbyterian Church was “literally packed full,” crowded with more people than he’d seen before with aisles full, the entry full and people even sitting around the altar. Doten called Earle’s sermon on Samuel meeting Rebecca at the well “pretty good.” [75] However, a few days earlier, Doten attended a revival meeting at the Episcopal Church where he noted there was a good house but the sermon was “not much.”[76]

Even though Doten gave Earle mixed reviews, the churches in Virginia City considered themselves blessed with the three largest—the Presbyterian, Methodist and Episcopal—sharing equally in the fruits of the revival.[77] The Presbyterian Church received 24 new members the Sunday after Earle’s departure and another 14 new members in June. Rev. Martin of the Presbyterian Church and Rev. Wickes of the Methodist Church continued nightly preaching for a period of time after Earle’s departure.[78]

After three weeks in the mining metropolis of Virginia City, Earle moved to Carson City, the capital of Nevada. As a guest of Governor Henry G. Blasdel, Earle remained in Carson City for 12 days. After his first meeting on Thursday, May 23, preaching to a full house at the Presbyterian Church, Earle informed those gathered that he needed rest and would not preach again until Sunday. He had been preaching several times daily, with never more than two days of rest, since the seventh of October. On Sunday, May 26, Earle preached in the Methodist Church at 11 A.M. and 7:30 P.M. The Presbyterian Church canceled services so their members could join in the revival. Later in the week the meetings moved back to the Presbyterian Church, at 3 and 7:30 P.M., and then back to the Methodist for the final service on 4th of June.[79] Two weeks later, the Reverend A. F. White of the Presbyterian Church received 30 new members. A total of 48 new members were added to the roll of the Carson City Presbyterian Church in 1867.[80] The effects of Earle’s ministry were certainly felt.

In a sermon preached on the occasion of his 50th anniversary of ordination, Earle recalled an event from his ministry in Carson City. A Welshman, who had heard of Earle’s preaching, traveled twenty-five miles to meet him. Two decades earlier, in Wales, this man heard a sermon which had impressed him, but had not changed his life. Upon meeting Earle, he “gave himself to Christ and went to work for others.” Earle noted that he had only been “permitted to reap what the Welsh minister had sowed.”[81]

After Carson City, Earle canceled plans for a trip to Austin, in central Nevada, due to fatigue.[82] He decided to move toward the coast and quickly wrap up his revivals in order to sail back East as soon as possible. He crossed the Sierras, into California, and commenced work in the twin towns of Nevada City and Grass Valley. These two towns, only four miles apart, were mining centers. In Earle’s biography, he placed his work in Nevada City first and then Grass Valley, but newspaper accounts reverse the chronology.[83] Grass Valley was a hard rock mining district with gold ore imbedded in quartz. It was said of the town that “everyone talked quartz, ate quartz and drank quarts.”[84] The local newspaper welcomed Earle to a promising field of labor, one in which many “consider themselves fire-proof.” The reporter hoped Earle could move “some of their flinty hearts.” In another article, the columnist compared Earle to Goldsmith’s description of a minister in Deserted Village, “fools who came to scoff remained to pray.” While in Grass Valley, Earle held afternoon meetings in the Congregational Church and evening meetings in the Methodist Church. The crowds were so thick that many “anxious listeners” gathered around the church’s windows to hear and see Earle.[85] After leaving the area, it was reported that the Congregational Church in Grass Valley had added 12 new members. A month later they added another 16 new members. In Nevada City, the Congregational Church had increased by 28 with 10 more considering making a commitment. The Methodist Church added 44 members and “quite a number of converts joined the Baptist Church.”[86]

The final city on Earle’s Pacific Coast tour was Santa Cruz, a coastal resort town south of San Francisco known as “the Newport of the Pacific.” Earle was only able to stay a few days in the city, working with the Congregational and Methodist Churches.[87] Upon leaving Santa Cruz, Earle made quick preaching stops in San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland, before boarding a steamer for the East Coast. According to a letter he wrote to The Pacific, Earle had preached five hundred sermons and worked with eleven different denominations in his nine-month journey through California, Oregon and Nevada.[88]

On board the ship bound for Panama, the Reverend A. B. Earle and his wife were joined by the Rev. William M. Martin and wife, from Virginia City. Martin had recently resigned as pastor of the church and left the Pacific Coast due to his wife’s health.[89]

The Impact of Earle’s Revivals

The Protestant Church on the Pacific Coast never enjoyed the influence it had on the Northeast; nonetheless, the revivals of A. B. Earle were successful. The Reverend William Martin of Virginia City may have overstated it a bit when he reported to the Presbyterian Home Mission Society that “the Pacific is blossoming like the rose.”[90] Yet most if not all churches that participated in the revivals grew, if only for a short while. At the end of 1867, the California Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church reported 1,200 new members, an increase of more than twenty-five percent. “This must be largely attributed to the labors of the Rev. A. B. Earle,” the annual report noted.[91] In an editorial late in the year, The Pacificreported an encouraging increase in moral and religious life in mining communities.[92] Due to pressure upon the owners, mines in Nevada began closing on the Sabbath for a short while and four years later a Virginia City newspaper recalled Earle’s revivals as an important religious event in the life of the community.[93]

A detailed study of those joining First Presbyterian Church in Virginia City provides a portrait of Earle’s work in the city. In the six weeks following Earle’s revivals, the Presbyterian congregation received forty new members, a significant number for a small congregation. Nine members joined by baptism indicating they had no previous church experience. Twenty-two individuals joined by making a profession of faith. These individuals would not have been active in a church with which they could have transferred their membership. Only nine individuals joined the church by transferring their membership from another congregation and most of these were from one extended family. Interestingly, in an overwhelmingly male community, twenty of those joining the church, half of the total, were women. Of those who joined the Presbyterian Church, half had moved out of state by the 1870 census, a statistic that demonstrates the transient nature of mining communities. However, many of those who joined were active into the 1880s and two remained members well into the twentieth century.[94]

Church membership gains within a mining community were short-lived. “Neither sinners nor the godly would remain in the towns to reap what they had sown, according to Ralph Mann’s history of Grass Valley and Nevada City.”[95] Mining communities were transient by nature. Even larger communities with long producing mines, such as in Grass Valley and on the Comstock, experienced a frequent turnover in population.[96] This mobilization created problems for churches depending on a stable population base. “Get in, get rich, and get out,” had been the mining philosophy since the beginning of the gold rush in 1849.[97] This mobility created problems for ministers used to a stable population with whom to labor.

Two other problems are often cited as hindrances to church work in the West during the mid-19th century. One was the lack of women. However, as the Virginia City congregation demonstrated, women were drawn to Earle’s revivals. Even though there may not have been as many women, as a percentage of the population, as compared to the East, women were present and active in the churches. A second hindrance cited has been the youthfulness of most residents of the West. Certainly, the West was younger than the rest of the nation, and many of these single young men interested in adventure were either drawn into the saloons or willing to experiment with new forms of religion.[98] However, it was the prevailing opinion in the nineteenth century that the ideal time for conversion was when a man or woman was young, still in their teens. [99] If the population was youthful, by this belief, they should have been more receptive to Earle’s preaching. But the truth is that, by the time Earle revivals began, the West was aging. Miners who had headed to California in their late teens would have been in their thirties by the mid-1860s, far past the ideal age for conversion according to nineteenth century wisdom.

Finances were another concern for western churches. Earle, however, didn’t experience this problem. Alf Doten, the newspaper editor from Gold Hill, Nevada recorded what he called “profits” from Earle’s revival. According to Doten, Earle raised “$6,000 from Marysville, $6,500 from Placerville, a probable $3,000 from Virginia City and proportional amounts from other towns and cities.”[100] From previous comments, we can see that Doten didn’t approve of Earle’s work and felt the “profits” were excessive. Even if he exaggerated Earle’s income, the offerings at the revivals had to be considerable to pay the cost of some of the halls used for the revivals. As has already been shown, the rent in San Francisco was fifteen thousand dollars, an enormous sum in 1866. Although Earle didn’t record his “revival profits,” he did note that the citizens of Virginia City gave him a thirty-pound brick of silver upon his departure. The Wells Fargo & Company shipped it back east for him, free of charge.[101] Interestingly, Alf Doten noted in his journals that Earle received two “big bricks of bullion,” one from Virginia City and another from Gold Hill.[102] Whether these were used to cover the cost of the revivals or considered by Earle as salary is unclear. Near the end of his ministry, Earle calculated his average income at three dollars a sermon, a sum averaging $1,188 a year.[103]

Throughout Earle’s West Coast travels, newspaper reporters continually remarked that Earle was not a raging sensationalist as they’d expected. As one columnist in Sacramento put it, “his words were plain, homely Saxon—intelligible to children; his imagination, which some thought deficient, was powerful grasping subtle spiritual truths.”[104] Another reporter in Petaluma wrote, “His language is plain, and his rhetoric far from perfect, but he rivets attention and seems to enforce conviction by his very earnestness.”[105] The sermons Earle included in his autobiography, “The Unpardonable Sin” and “Joy Restored,” which have already been reviewed, show two approaches Earle used in the pulpit. The first emphasized the urgency of the gospel while the second lifted up the benefits of Christian living. Like the revivals of 1858, the revivals Earle conduct had none of the excesses of the Cane River revivals early in the Second Great Awakening that had raised the eyebrows of many Protestant ministers in the East. Earle’s simple style endeared him to many of the ministers he worked with and his autobiography contains many letters of thanks from those with whom he’d labored.[106]

It appears that Earle concentrated his efforts on reaching the Anglo-population. Newspaper reports as well as his own accounts of the revivals do not mention any efforts to reach other ethnic and racial groups. Earle’s revivals mirror the 1857-58 revivals, strengthening the Anglo-Protestant majority, even though their majority status would be short-lived.[107] By not taking this into account, the Protestant leaders in California set themselves up to fail for the West experienced religious and ethnic plurality before the rest of the nation.

Toward the end of the 1857-58 revival, an editorial in the New York Observer asked “what fruits the revival should yield?” The newspaper reported the revival had converted thousands in the city and tens of thousands across the country, but noted that was small when compared to the “vast multitude” who are unchanged. Therefore, the editorialist suggested that things would not change much. A few criminal converts wouldn’t make a dent in crime, nor would there be less fraud on Wall Street, he assumed.[108] The same could be said for Earle’s West Coast revivals. He emphasized the necessity for individual reforms without challenging the social evils of the West such as prostitution, slavery among Chinese, gambling, as well as widespread business fraud, especially in mining stocks. Instead, Earle focused his ministry on preaching to individuals with hopes that those changed by the gospel would, in turn, change society. High expectations and naiveté concerning reality are hallmarks of Western history, according to Patricia Nelson Limerick.[109] Protestant leadership in the West demonstrated both. The Pacific Coast never became the bastion of Protestantism as those who had invited Earle had hoped. The revivals by the Reverend A. B. Earle strengthened the Anglo-Protestant Churches in the short term, but the seeds for a changing religious landscape had already been sown. By the end of the nineteenth century the Golden State had the feel of a “new burned over district” as various new religious groups flooded the American West and reaped their harvests.[110]

[1] The Reverend A. B. Earle, Bringing in Sheaves (Boston: James H. Earle, 1872), 128-144.. Earle preached this sermon throughout his revivals on the West Coast. In his autobiography, Earle indicated the sermon was preached at October 14, 1866 at the Union Hall in San Francisco. Interestingly, a transcription of that sermon in The Pacific (San Francisco: 1 November 1866) does not have the Civil War story at the end. Instead, Earle ended by drawing upon the story of Moses’ response in the wilderness when serpents attacked the people of Israel. The two different published versions of the same sermon probably illustrate Earle’s continual reworking of sermons that he preached over and over again.

[2]Timothy L. Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Abingdon, 1957; repr., Baltimore, John Hopkins Press University, 1980), 141.

[3] Paul K. Conkin, Cane Ridge: America’s Pentecost (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990).

[4] William G. McLoughlin, Revivals, Awakening, and Reform (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 128-120. Also see Keith J. Hardman, Charles Grandison Finney: Revivalist and Reformer (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1987).

[5] Sandra S. Sizer, Gospel Hymns and Social Religion: The Rhetoric of Nineteenth Century Revivalism (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978), 85. The years 1830-1860 were known as the “Sentimental Years” due to the organization of benevolence societies that, according to William Warren Sweet, were the “legitimate children of revivalism.” See William Warren Sweet, Revivalism in America: It’s Origin, Growth, and Influence (New York: Abingdon, 1944), 159

[6] Kathryn Teresa Long, The Revival of 1857-58: Interpreting an American Religious Awakening (New York: Oxford, 1998), 13. For additional description of this awakening, see Hardman, Charles Grandison Finney, 430-433.

[7] Smith, Revivalism,, 62. It should be noted that the revival was popular in the South and although many hoped for an end to slavery, the revivals themselves tended to be conservative and its leaders discouraged the discussion of divisive issues. See Richard J. Carwardine, Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 294 and Long, The Revival of 1857-58, 125.

[8] Those converted or influenced by the revivals include D. L. Moody; Lottie Moon (later to be a Baptist missionary to China), Charles Briggs (later to be a renounced “liberal” professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York City); and Charles Crittenton (a wealthy owner of a drug company who became a revivalist later in his life and funded rescue homes for wayward women). See Long, Revival of 1857-58, 127-132. Others having their careers boosted by in the revival included Methodist John S. Inskip (later to be a leader in the holiness movement), Alfred Cookman, Reuben A. Torry and J. Wilbur Chapman. See Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform, 74. Another lesser-known convert of the revival was David Henry Palmer, a college student converted in Rochester, New York. After college, Palmer attended Auburn Theological Seminary and became the first Presbyterian pastor in Virginia City, Nevada. See Charles Jeffrey Garrison, “David Henry Palmer: A Pastoral Baptism in Western Mining Camps, American Presbyterians: Journal of Presbyterian History, Vol. 72, No. 3 (Fall 1994), 181-2

[9] Long, Revivals of 1857-58, 44-45, 105, 71.

[10] Sizer, Gospel Hymns and Social Religion, 112-113.

[11] Long, Revival of 1857-58, 61, 87, 104, 111, 118 & 125.

[12] Timothy Smith, in his 1957 study of the mid-century revivals, suggests that perfectionism, as well as the holiness and ethical concerns played a more significant role. Smith uses Earle as an example the role perfectionism played in the mid-century revival. See Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform, 139. Later studies have challenged Smith’s conclusions. See Long, The Revival of 1857-58, 4.

[13] Rev. A. B. Earle, The Rest of Faith (Boston: James H. Earle, 1881), 62, 76-81. Other historians have dated Earle’s sanctification during the 1858-9 revivals. See Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform, 139.

[14] Presbyterian and Reformed Churches, in particular, had a difficult time accepting this doctrine. The two warring Presbyterian factions, the Old and New School, were united in opposition to perfectionism. See George Mardsen, The Evangelical Mind and the New School Presbyterian Experience (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970), 80-81.

[15] Kevin Starr, Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (New York, Oxford University Press, 1973; rptr, Santa Barbara: Peregrine Smith, 1981), 71-72, 85-86.

[16] The idea that California’s gold was hidden until the state was securely in American hands was taught not only by mainline Protestants. The famous Unitarian preacher, Thomas Starr King also preached God’s providence in bringing California into the Union. See Edward Arthur Wicher, The Presbyterian Church in California, 1849-1927 (New York: Frederick H. Hitchcock, 1927), 28 and Starr, Americans and the California Dream, 103-104.

[17] The Pacific began publishing on 1 August 1851 as a joint effort of Congregational and New School Presbyterians. The goal of the newspaper was to encourage the work of Protestant Churches on the West Coast. See P. Mark Fackler and Charles H. Lippy, editors, Popular Religious Magazines of the United States (Westport, Connecticut: Gleenwood Press, 1975), 373-380.

[18]”Evangelization on the Pacific Coast: Mistaken Policy,” The Pacific, San Francisco: 17 August 1865; The Pacific, 7 September 1865; ”The Possible Results of Revivals in California,” Ibid, 23 March 1865.

[19]Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform, 74, 118-119. For a description of Taylor’s activities in California, see Starr, 78-82.

[20] Starr, 73, Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp, Religion and Society in Frontier California (New Haven: Yale, 1994), 94-95.

[21] “Welcome Home, A Sermon preached in Memory of Rev. Geo. W. Finney at the 1st Congregational Church, Oakland, 18 April 1865,” The Pacific 27 April 1865.

[22]Smith, 142. “The Week of Prayer at the New Year,” The Pacific, 13 December 1866. See also Charles Jeffrey Garrison, “How the Devil Temps Us to Go Aside from Christ:’ The History of First Presbyterian Church of Virginia City, 1862-1867.” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring 1993), 22; and “David Henry Palmer: A Pastoral Baptism in Western Mining Camps, American Presbyterians: Journal of Presbyterian History, Vol. 72, No. 3 (Fall 1994), 181-2.

[23] “Revival in Santa Clara,” The Pacific, 20 November 1863.

[24] For a summary of this revival, See Garrison, “David Henry Palmer”, 182.

[25] See George M. Mardsen, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 11-13, and James H. Moorhead, American Apocalypse: Yankee Protestants and the Civil War, 1860-1869 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), 56.

[26]For a study of Lincoln memorial sermons, including two from California, see David B. Cheesebrough, “‘God Has Made No Mistake:’ The Response of Presbyterian Preachers in the North to the Assassination of Lincoln” American Presbyterian: Journal of Presbyterian History 71:4(Winter 1993), 223-232. Many of the Lincoln memorial sermons were published. West Coast examples include the Reverend J. D. Strong, “Discourse on the Death of Abraham Lincoln” published by the Larkin Street Presbyterian Church of San Francisco and the Reverend C. C. Wallace, “Funeral Address, On the Occasion of the Funeral Obsequies in Memory of Abraham Lincoln by the Placerville Tri-Weekly News. Copies of the above sermons from a box titled “Presbyterian Church in California” Box 3, Pacific School of Religion, Berkeley, California.

[27]”Meeting of the S. F. Ministerial Union,” The Pacific, 12 July 1866. The Rev. E. P. Hammond, the “children’s evangelist’s” would later spend eight weeks in San Francisco in 1875, drawing large crowds. See Douglas Firth Anderson, “San Francisco Evangelicalism: Regional Religious Identity, and the Revivalism of D. L. Moody,” Fides et Historia: Official Publication of the Conference on Faith and History, vol. 15 (Spring/Summer 1983), 47-8.

[28]”Meeting of the S. F. Ministerial Union,” The Pacific, 12 July 1866; “Religious Intelligence,” The Pacific, San Francisco, CA, 30 August 1866.

[29]Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 239.

[30]Rev. A. B. Earle, D.D., Work of an Evangelist: Review of Fifty Years, (Boston: James H. Earle, Publisher, 1881), 9, 12 & 14.

[31] Earle’s autobiography, Bringing in Sheaves, spiritual autobiography The Rest of Faith, and hymnal titled Revival Hymns are quoted elsewhere in this paper. The book of devotions was titled The Morning Hour (Boston: James H. Earle, nd).

[32] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 81-88.

[33] Ibid, 28. The Reverend A. B. Earle, D.D., “Faith” The Evangelistic Cyclopedia: A New Century Handbook of Evangelism. (New York: George H. Doran, 1922, 306.

[34] Sizer, Gospel Hymns, 23, 39 & 20; A. B. Earle, collector, Revival Hymns (1865; Boston: James H. Earle, 1870), title page. At the 1870 edition, 30,000 copies of this little hymnal had been published. The hymnal measured only 3 inches by 5 inches and contained 109 hymns.

[35] Ibid, 285. Most likely, Earle traveled to California through Panama, taking a steamer from New York to Panama, crossing the isthmus, and then taking a steamer up the Pacific Coast to San Francisco.

[36] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 289.

[37] Ibid, 293; Earle, Work of an Evangelist, 23, 19.

[38] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 289.

[39] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 293. See also Alta California (San Francisco), 20 October 1866 and 10 November 1866; “Union Meeting for Children,” The Pacific, 25 October 1866.

[40] “Religious Revival,” Alta California, 19 October 1866. Earle’s autobiography, Bringing in Sheaves, published in 1872, contains over 90 pages dedicated to his nine month experience in the American West.

[41] Alta California, 11 November 1866. See also The Pacific, 15 November 1866. “The Daily Prayer Meeting,” The Pacific, 22 November 1866.

[42] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 295-297.

[43] A brief description of the revival is found in a letter from Henry Kendall in the Sheldon Jackson’s Scrapbook (35a), Manuscript Collections, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia. A quote on this clip can be found in Garrison, “How the Devil Tempts Us to Go Aside from Christ, 19. See also the Toulumne Courier (Columbia, CA) 20 February and 5 March 1864.

[44] For a detail examination of this revival, see Garrison, “David Henry Palmer,” 182. The Pacific, 18 October 1866.

[45]Sandra Sizer Frankiel suggests Laurentine Hamilton, pastor of First Presbyterian Church, Oakland, was thumbing his nose at revivalism during Earle’s tenure on the West Coast. The Presbytery of San Jose defrocked Hamilton in 1869, after he challenged orthodox views on immortality and eternal punishment. However, since Presbyterians were supportive of Earle’s work, it seems more likely he either kept his views to himself or developed his unorthodox thoughts after these revivals. See Sandra Sizer Frankiel, California Spiritual Frontiers: Religious Alternatives in Anglo-Protestantism, 1850-1910 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 32-37.

[46] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 297-299; The Pacific, 20 December 1866.

[47] Ibid, 299.

[48] Ibid,, 302-303.

[49] The Pacific, 17 January 1867. It is interesting that Earle’s preaching in Sacramento was over Christmas and New Years. No mention of these holidays are in Earle’s or The Pacific’s accounts of the revival.

[50] Petaluma Journal and Argus (Petaluma, California), 17 January 1867.

[51] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 305; “Thinking and Acting,” Petaluma Journal and Argus 24 January 1867. William C. Pond, Gospel Pioneering: Reminiscences of Early Congregationalism in California, 1833-1920 (Oberlin, Ohio: The News Printing Company, 1921), 96-97. According to The Pacific, 7 February 1867, 36 persons joined the Congregational Church in Petaluma.

[52] Pond, Gospel Pioneering, 97.

[53] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 307.

[54] “The Revival in San Jose” The Pacific 21 February 1867: Ibid, 7 February 1867.

[55] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves 307-310; The Pacific, 28 February 1867.

[56] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 311-312; “Revival in Santa Clara,” The Pacific, 7 March 1867.

[57] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 312; Marysville Daily Appeal (Marysville, California), 17 February 1867. Earle refers to the city’s hostility to religion in Bringing in Sheaves, 312. The beginning of the revival was reported in the Marysville Daily Appeal 3 February 1867. It was later suggested that 100 persons were converted before Earle’s arrival. Ibid, 6 March 1867. Ibid, 19 February 1867; 24 February 1867. The Reverend William Wallace Brier organized the Presbyterian Church in Marysville in 1850. See Earl Ramey, “The Beginning of Marysville, Part III,” California Historical Society Quarterly, 15:1 (1936), 47. Marysville Daily Appeal, 21 February 1867, 24 February 1867. Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 315.

[58] “A Large Meeting,” The Pacific, 14 March 1867; Marysville Daily Appeal, 5 March 1867.

[59] “Marysville Religious Items,” The Pacific 11 April 1867. This same article indicated 84 had sought admission with the Presbyterian Church and 70 had been accepted into membership with 23 baptisms. 20 individuals were baptized at the Baptist Church a week after Earle departed. Marysville Daily Appeal, 10 March 1867. Before Earle’s arrival, the Methodist Church had already received 38 new members. Ibid, 12 February 1867.

[60] “The Revival,” Ibid, 26 February 1867.

[61] Earle, Bringing In Sheaves, 74, 75-76.

[62] Ibid, 63 and 65, 74.

[63] “Revival in Placerville,” The Pacific 21 March 1867.

[64] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 317.

[65] The Pacific, 21 March 1867; “Notes from the Pacific Coast,” The Christian Advocate, (New York) 7 February 1867. Interestingly, The Christian Advocate, which was a newspaper of the northern Methodist Episcopal Church, did not report on Earle’s revivals in the American West from August 1866 through July 1867; Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 319.

[66] “Rev. Mr. Earle,” The Pacific, 18 April 1867.

[67] As quoted in Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 320-321.

[68] Ibid, 322, 327; Territorial Enterprise (Virginia City, Nevada) 28 April 1867.

[69] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 331; First Presbyterian Church of Virginia City, “Minutes of Session” 22 April 1867. Manuscript Collections, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia.

[70] Territorial Enterprise, 28 April 1867.

[71] Walter Van Tilburg Clark ed., The Journals of Alf Doten, 1849-1903 (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1973), 925. (Hereafter cited as Doten).

[72] As quoted in Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 335.

[73] Doten, 926.

[74] Doten, 927.

[75] Doten, 928-929. Doten must have confused Samuel for Abraham’s servant who met Rebekah at the well. See Genesis 24:15.

[76] Doten, 927.

[77] Editorial Visits” The Pacific, 11 July 1867. This article stated that Virginia City also had a Baptist congregation meeting in the Courthouse and two colored [sic] churches meeting in their own buildings. No mention was made of these three churches benefiting from Earle’s labor.

[78] “First Presbyterian Church of Virginia City, “Minutes of Session.” 27 May 1867, 9 June 1867; Departure of Rev. Mr. Earle,” Territorial Enterprise, 23 May 1867.

[79] The Daily Appeal (Carson City, Nevada) 22 May 1867; 24 May 1867; 26 May, 28 May 1867; 7 June 1867.

[80] “First Presbyterian Church of Carson City, Nevada—75th Anniversary Celebration Program,” 7 June 1936. A copy of this program is in the Manuscript Collection of the Presbyterian Historical Society in Montreat, North Carolina.

[81] Earle, “Revival Like A Harvest,” Work of an Evangelist, 41-42.

[82] William M. Martin, “Nevada” Presbyterian Monthly October 1867.

[83] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 341-344. Grass Valley Union (Grass Valley, California) 2 June 1867, 25 June 1867; The Pacific 4 July 1867, 11 July 1867.

[84] Ralph Mann, After the Gold Rush: Society in Grass Valley and Nevada City, California, 1849-1870. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1982), 131.

[85] “Rev. Mr. Earle,” Grass Valley Union, 25, 29, and 22 June 1867.

[86] “Religious Intelligence,” The Pacific 11 July 1867, 25 July 1867.

[87] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 344; “Revival of Religion,” The Pacific 18 July 1867.

[88] Ibid, 245-246; “To the San Francisco Ministerial Union,” The Pacific 1 August 1867.

[89] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 349; Minutes of Session, First Presbyterian Church of Virginia City, 9 August 1867. According to this entry, Martin had informed the Session of his resignation on 14 July 1867.

[90] William M. Martin, Presbyterian Monthly (October 1867).

[91] C. V. Anthony, A.M., D.D., Fifty Years of Methodism: A History of the Methodist Episcopal Church Within the Bounds of the California Annual Conference from 1847 to 1897 (San Francisco: Methodist Book Concern, 1901), 282.

[92] “Editorial Visits,” The Pacific 24 October 1867.

[93] “The Observance of the Sabbath in Nevada,” Ibid, 15 August 1867. The closing of mines did not continue for very long. During most of its history, mines on the Comstock ran seven days a week. Even when they were closed, the miners had to do their shopping and laundry on Sunday: Territorial Enterprise, 18 April 1871.

[94] Data for those joining the Presbyterian Church in Virginia City obtained from Session Minutes and the 1870 census. For a complete breakdown of those joining the church in the aftermath of Earle’s revivals, see Charles Jeffrey Garrison, “Presbyterians and Miners: The Church’s Response to the Comstock Lode,” Doctor of Ministry Dissertation, San Francisco Theological Seminary, San Anselmo, CA (2002), 219-220.

[95] Mann, After the Gold Rush, 38.

[96] For a summary of population trends, see Marion S. Goldman, Gold Diggers and Silver Miners: Prostitution and Social Life on the Comstock Lode (Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, 1981), 15-16.

[97] Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987), 100.

[98]See Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp, Religion and Society in Frontier California (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

[99] Thomas R. Cole, The Journey of Life: A Cultural History of Aging in America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 80-82.

[100] Doten, 927. On financial concerns of churches see Maffly-Kipp, Religion and Society in Frontier California 98.

[101] Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 335-336.

[102] Doten, 929

[103] Earle, Work of an Evangelist, 20. Earle’s salary was above most ministers of the era. One report which sought information from 1,000 ministers found that three fourths of all ministers made less than $1,000 a year, most making $350-$750. See “Ministers’ Salaries,” The Pacific 5 September 1867.

[104] “The Revival in Sacramento,” The Pacific 17 January 1867.

[105] “Revival,” Petaluma Journal and Argus 17 January 1867.

[106] See Earle, Bringing in Sheaves, 156-165, 178-183.

[107] Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest, 290. In one incident during the 1857-58 revivals, a freed African-American man was excluded from a New York revival. See Long, The Revival of 1857-58, 106. Although it may have occurred in isolated instances, the reports of Earle’s revivals never mention any work among Orientals or African Americans. Both groups lived and had churches in California and Nevada.

[108] “What Fruits the Revival Should Yield? New York Observer, (April 12, 1858), as quoted by Long, The Revival of 1857-58, 102.

[109] Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest, 29.

[110] Maffy-Kipp, Religion and Society in Frontier California, 183.