Jeff Garrison

Mayberry and Bluemont Churches

1 Corinthians 15:12-28

April 17, 2022

At the beginning of worship:

In a devotion for Easter a few years ago, Richard Rohr, reminded his readers that “Easter isn’t celebrating a one-time miracle as if it only happened in the body of Jesus and we’re all here to cheer for Jesus.” Sadly, he concludes, that’s what a lot of people think. Rohr places the seeds for Easter in Christmas, with the incarnation.[1] If God can become flesh (that’s incarnation), the resurrection naturally follows. The resurrection is what Easter is all about. Ask yourself, “What difference does the resurrection make for your life?” Remember, the empty tomb which we come to celebrate today is just the beginning.

Before the reading of Scripture:

In the 15th Chapter of First Corinthians, Paul provides the most detailed treatment of the resurrection found in scripture. It’s a long chapter. This morning, I will begin reading in verse 12. Here, Paul begins by pointing to objections being made about the resurrection. For Paul, the foundation of our hope in Jesus Christ is found in the resurrection to life everlasting. Yes, we will all die; we will cease to exist. But the grave is not the end! Later on in this chapter, Paul can ask: “O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?”[2] He can be that bold because he believes, as we proclaim in the Apostles’ Creed, “in the resurrection of the body and in the life everlasting.”

After reading Scripture:

People turn to the church when there is a death because we’re the only place that offers hope for something beyond our frail mortal bodies. In all the work I did on the history of Western Mining Camps, one of the surprising things I learned was how at the time of death, even people who religiously avoided the shadow of the steeple, would be brought back for a funeral.

Funerals in the Old West

The friends of Julia Bulette, Virginia City’s most famous prostitute, sought out the presbyterian minister for her funeral. Mark Twain in Roughing It has a wonderful tale about Buck Fanshaw’s funeral. Fanshaw, a leader of the “bottom-stratum of society” and based on a real-life character who had a relationship with Bulette, died. The local roughs elected Scotty Briggs to “fetch a parson” to “waltz Fanshaw into handsome” (their word for heaven). The dialogue between the minister and Scotty is classic Twain.[3] Although funny, it’s a reminder that at the time of death, we want the comfort only the church can offer: the hope in life everlasting in Jesus Christ.

The resurrection and how we live

But let me suggest that such comfort isn’t just for the dying. It’s also important for how we live our lives. Having faith in the resurrection allows us to be bold.

We must look no further than to John Knox, the great reformer of Scotland, to see boldness fortified by belief in the resurrection. Knox converted to the Protestant faith through the preaching of George Wishart. Knox first heard Wishart in Leith on December 13th, 1545. While Knox had began moving toward the Protestant movement with his study of Scripture, Wishart’s preaching sealed the transformation. Knox immediately became Wishart’s disciple and spent the next five weeks with him. Knox stuck by Wishart, even though he knew he was marked man. In early 1546, less than two months after the two met, Wishart was arrested and burned at the stake in St. Andrews.[4] Knox avoided such a barbecue, but ended up doing hard time as a prisoner, manning oars on a galley ship. Why would someone be so willing to risk their own life unless they really believe it’s worth it?

At death and in times of peril, the church is a symbol of our faith and the hope we have for something we can never fully comprehend in this life, the resurrection.

Exploring the text

Let’s look at our text. In verses 12 through 19, Paul plays the devil’s advocate. If there is no resurrection, it’s a big joke. If there is no resurrection, we are to be pitied. Of course, Paul doesn’t believe that. In verse 20, Paul shifts his argument with a powerful “BUT.” This change of direction wipes out the objections he’d just raised. “But Christ has been raised,” Paul proclaims; this truth makes all the difference in the world!

Adam’s sin

Paul begins by contrasting two men who represent more than themselves. Adam is not just our first-umpteenth great-granddaddy; he stands as the primal man, the representative of us all.[5] The death that comes through sin is something we all share. Interestingly here, Paul does not cite Eve or blame her for the first sin, the eating of the forbidden fruit. In this way, Paul is more enlightened than he is often given credit. Within the rabbinical tradition at the time, as can be seen in the Apocryphal literature, Ben Sirach lays the blame for sin and death on the first woman. After all, Eve was the first to nibble on that sinful fruit.[6] But Paul doesn’t go there. Instead, by using Adam as an archetype for all humanity, he shows that we all share in the blame for sin and in sin’s consequence: death.

Response to Adam: Jesus’ resurrection

However, there is good news. Although death came through a human being, so too has the resurrection come through a human being. Paul lifts the Christmas doctrine of the incarnation. In Jesus Christ, God became flesh! Christ is the first-fruit of the resurrection, a term that probably meant more to Paul’s audience than to us today. For you see, the Jews were to bring the first of the harvest, their first-fruits, to God as an offering of thanksgiving. We tend to give God what is left, not our first-fruit, which probably says a lot more about our spiritual state that we’d honestly like to admit. However, this isn’t about our giving, it’s about God’s gift, for God the Father gave us his first-fruit, in that of his Son.

All this is a part of God’s plan in history, Paul notes. It’s all a part of the great plan to destroy all authorities and powers that defy or challenge God. At the end, there will be nothing to draw our attention from the Almighty. All idols will be destroyed, all that which we fear will be removed, the last of which is death itself. With the removal of that great enemy which has haunted humanity since the beginning, we can worship God without fear or distraction.

Enemies under Jesus’ feet

Kenneth Bailey, in his commentary on First Corinthians, goes into detail about the meaning of Jesus placing all his enemies (the last one being death), under his feet. Bailey suggests that verses 24-27 could be removed and the reader wouldn’t notice. You can try this yourself, at home, just leave the verses out and see how it reads. So why did Paul insert this little segue? It’s to make a political point: Jesus is Lord!

If Jesus is Lord, that means Caesar isn’t Lord. He cites examples from the ancient world in which the ruler’s footstool often had engravings representing the kingdom’s enemies and when the ruler placed his foot upon the stool, he was making a statement about his power. When Christ has finished, there will be no possibilities of his enemies, including death, making a comeback![7]

Example of enemies underfoot from Korea

In the winter of 2000, I had the opportunity to spend a few weeks in Korea: preaching, sightseeing and mountain climbing. I visited the imperial city in Seoul, where the emperor once ruled, his throne built on a hill that allowed him to overlook the city. In 1910, Japan invaded Korea. The Japanese decided it was too dangerous to destroy the ancient throne, so instead they built a modern government building to block the view from the city. When there, a controversy over what to do with this building that was architecturally significant ensued. Many wanted to tear it down, which is what happened, but others wanted to relocate it. One of the more creative ideas, which caused a minor international incident with the Japanese, was to dig a hole and sink the building and then glass over the top. That way, the building would not be destroyed, but the Korean people could have the satisfaction of “walking over” or stomping on the visible representation of 40 years of Japanese occupation.

Enemies not under our feet, but Jesus’

The idea of our enemies being under our feet is still strong in our imaginations, as we can see from Korea. We can only imagine what kind of imagery Ukraine will come up with! Yet, we need to remember that in the eternal realm, we’re not conquerors, Christ is! We’re not the victors; we share in Christ’s victory. The enemies are not under our feet, but his. And they’re not our enemies, they’re his enemies. We might even be surprised to find some of our enemies on Jesus’ side. All things are possible with God. But the important thing isn’t who’s in and out, it’s whether or not we are on Jesus’ side. Consider this, if we are out, we could end up being a footstool.

Conclusion

Friends, we’re mortal and we’re going to die. We know that, even if we sometimes act as if we don’t. As for when or how we’ll die, we don’t know. But we live with hope. We’re told that Jesus is the first fruit of the resurrection. The implication here is that Jesus will not be the only one raised. Jesus’ resurrection is not the exception to the rule. Jesus’ resurrection is the start of something new: all who trust and accept him will live with him eternally.[8]

And because we put our faith in Christ and through him have faith in the resurrection, we can live this life without fear. We can be like John Knox, following George Wishart to the stake. We can be bold on behalf of our Savior. Friends, live fiercely, in the knowledge that in life and in death, we belong to Jesus Christ.[9] Amen.

[1] https://cac.org/the-death-of-death-2019-04-21/

[2] 1 Corinthians 15;55.

[3] Mark Twain, Roughing It (1872), Chapter 47. See also Charles Jeffrey Garrison, “Of Ministers, Funerals, and Humor: Mark Twain of the Comstock,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 38, #3 (Fall 1995).

[4] Jane Dawson, John Knox (New Haven: Yale, 2015), 28-32.

[5] Hans Conzelmann, First Corinthians: Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1975), 268.

[6] Kenneth E. Bailey, Paul Through Mediterranean Eyes: Cultural Studies in 1 Corinthians (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Press, 2011), 443. See Sirach 25:24

[7] Bailey, 447.

[8] William F. Orr and James Arthur Walther, I Corinthians: The Anchor Bible (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1976), 330.

[9] Taken from the opening question of the Heidelberg Catechism.

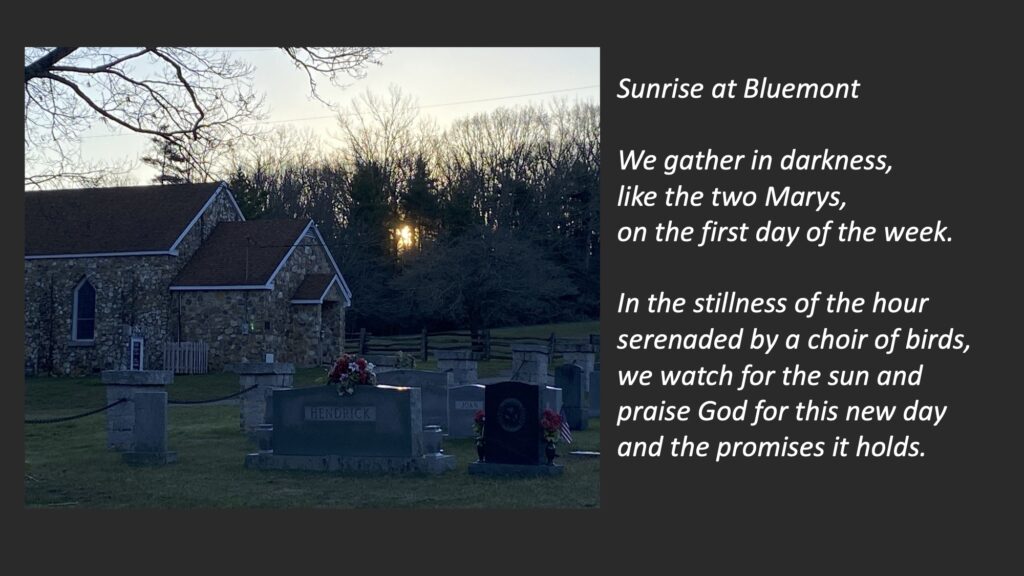

Sunrise over Buffalo Mountain