I am trying to catch up on reading reviews. Below are four reviews that contain fiction, poetry, philosophy, and history. I will start with the lighter books and move on to the more heavy ones. There’s something here for everyone!

Aaron McAlexander, This Old Store

(Stonebridge Press, 2014), 95 pages including photos and maps.

There really is a place called Mayberry. It’s located along the Blue Ridge Parkway in Southwestern Virginia, twenty-some miles from Mt. Airy, NC. There was never much of a town here, just a few businesses and some farmers. Until the 1930s, there was a Post Office here. The store, where the Post Office resides, is still in business. The other reminder of the community that once existed is Mayberry Presbyterian Church. Aaron McAlexander, along with his late uncle, John Hassell Yeatts, have done their best to preserve the stories of this community. This is the fourth book I’ve read by McAlexander. It’s an easy read and a joy.

Throughout the countryside in these parts, there are lots of old boarded up stories. Many were two story stores, like Mayberry Trading Post. Most have been closed for decades. The Mayberry Store, which was built in 1892, remains open mainly because it is adjacent to the Blue Ridge Parkway. Today the store sells snacks, crafts, and souvenirs, along with jars of canned local treats from jams to chowchow.

This was once a community center. People picked up their mail in this old building, in addition to obtaining kerosene for their lanterns and later gasoline for their car or tractor. Hardware and tools along with that which they couldn’t produce themselves could be purchased at the store. The store would also trade for locally produced goods, from apples to chestnuts, which the storekeeper hauled to Mt. Airy or Stuart, Virginia to sell. While the storekeeper never sold alcoholic drinks, there would often be a bootlegger around who would have a bottle or two hidden nearby so those who wanted a nip could be satisfied. On slow days, checkers would be played.

Over the years, the store has changed hands many time (it’s been for sale for the last few years and from the scuttlebutt I recently heard, may be about ready to be sold again). McAlexander outlines these changes along with recalling stories from his mother and grandparents to his own stories of growing up in the area in the 1940s and 50s.

Other reviews of McAlexander books I’ve read: The Last One to Leave Mayberry, Shine On Mayberry Moon, Greasy Bend: Ode to a Mountain Road.

###

Ivan Doig, The Bartender’s Tale

Narrated by David Aaron Baker, 14 hours, 47 minutes; (2012, audiobooks, 2013)

It has been a while since I read Doig. Almost a quarter century ago, when I was living in the Great Basin of the American West, I discovered Doig and read two of his memoirs: House in Sky: Landscapes of a Western Mind and Heart Earth. Living in an area where there were still sheepherders, Doig’s writings felt familiar. This is the first fiction I’ve read (actually listened to) by him and, God willing, it won’t be the last.

The book is told through the eyes of a child. This allows the author to lead us, in Rusty’s mind, down some wrong paths as a boy’s mind will often do. Is she my mother? What will happen if my father falls in love? You’ll have to read the book to learn the answers to those question and others that I ask.

The story begins in the early 1950s, when Rusty was six years old and being raised by an aunt with a couple of older boys in Arizona. He’s looking forward to school just so he can have time away from these taunting nephews. Then, like a good western, an outsider rides into town to save him. He is reunited with his father, Tom Harry, whom he had only seen occasionally. His father lives in Gros Ventre, Montana, where he runs the Medicine Lodge Saloon.

The novel then jumps ahead to the summer of 1960. Rusty is now twelve years old. This is a summer of discovery. Rusty meets Zoe, a new girl in town whose parents have purchased the Top Spot, the local diner. The two of them make quite a pair spying on everyone and trying out new characters as if they’re in theater. Throughout the summer, as everyone wonders if Kennedy will be the new President, there is a string of characters that make their way into town. One is Delano, an oral historian who wants to learn about the Fort Peck Dam project from Tom, who ran a bar there during the Great Depression. Delano is also interested in language patterns, which helps provide insight into the catchy phrases often thrown around by those visiting the bar. Also swinging into the Medicine Bar is Proxy, a former dancer in Fort Peck. In tow is her trouble daughter, Francine. Is Francine Rusty’s half-sister? Or his sister? Can Francine run one of the best-known saloons in Montana?

There is a lot packed into that summer of 1960, as Doig slowly fills in the details of Rusty’s inquisitive mind. Doig captures the western dialect, which helps create a delightful come-of-age story. He captures the life of the sheepherders along with working into the story a Class D League baseball team which he describes as being one step up from a picnic softball game. There is also some fishing. Doig captures the beauty of place as he describes Montana and the Medicine Bar.

Quote from their road trip from Arizona to Montana:

“My father always said, when stopping on a road trip in a place to pee, “nice joint you have here, even if it was as gloomy as a funeral parlor. I supposed I learned something of professional courtesy from these stops.”

###

Raymond Carver, All of Us: The Collected Poems

(1996, New York: Vintage Contemporaries, 2000), 386 pages including index, appendixes, plus Introduction and Editor’s Preface

I have only recently become acquainted with the writings of Raymond Carver who died at the age of 50 in 1988. He’s perhaps best known for his short stories, but I decided to sample a collection of his poetry. This collection was gathered and published after his death. While I was familiar with the poetry of Tess Gallagher before reading his volume, I did not know that she was Carver’s last wife. She provides both the Introduction to this work along with an extensive essay in the appendixes that served as an introduction to the last collection of Carver’s poetry.

The book begins with earlier poems which are often raw and sometimes vulgar. Some reflect the views of an alcoholic and of loss relationships. Other poems in this section come from the author’s travels, especially in Europe. Often, in these poems, he weaves in history with his own experiences. Other travels take him into the wilderness of the American West, and on fishing trips. One poem that stood out to me was “To My Daughter,” where he warns her that alcoholism runs in the family and warning her not to drink like she’d seen her parents do.

I found the poems in the last half of the book, written after he had quit drinking, to be more filled with wonder and gratitude. Here there are even more poems set around the Pacific Northwest. Fishing often comes up. Mixed into this section are many poems by Anton Chekhov. Sprinkled throughout the book are quotes and poems from other authors. Carver also brings other authors into his poetry such as Franz Kafka in “The Moon, The Train.” As the reader comes to the “first” end of the collection, the author knows he’s living on borrowed time. I had a sense of grace reading these poems.

But just because I reached the end of the collection didn’t mean I was out of poems to read, as the first appendix contained a group of “uncollected poems” from No Heroics, Please. His wife’s essay at the end is also worth reading as it sheds much light onto their life together and the last group of poems in this collection.

This is a large collection of poems. I spent a month and a half reading through them, often before bed, sometimes reading a poem several times. For those interested in poetry, this volume appears to me to be a “must read.” Yes, some of the poems especially in the first part of the book can be quite raw, but so is life for many people. As one continues to read, one will also find grace and hope and beauty.

###

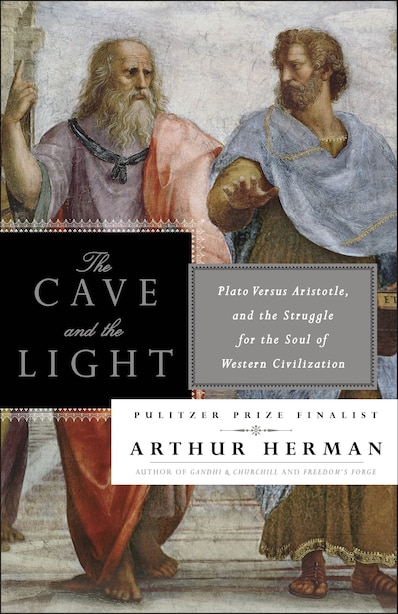

Arthur Herman, The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Artistole and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization

(New York: Random House, 2014), 676 pages including notes, bibliography and index, or 25 hours and 26 minutes on Audible.

I started listening to this book on Audible but became so engrossed into Herman’s survey of Western thought that I ended up buying the book so I could go back and read and study sections of it. This is a massive undertaking. Herman begins by describing Raphael’s painting, “The School of Athens” which is in the Vatican. Over the next few hundred pages, he will expand upon the various philosophers in the painting. He’s concentrates primarily on Plato and Aristotle, who are depicted in two camps on the canvas. On Plato’s side is Socrates, Pythagoras, Speusippus, Zenocrates, Plotinus, Epicurus, the Arab scholar, Avernoes, and Heraclitus. In Aristotle’s camp are Eudemus, Theophrastus, Ptolemy, Euclid, and Stabo. From these two camps come a creative tension between the idealist Plato and the more practical Aristotle that has driven Western thought for the past 2500 years.

Herman takes the reader on a journey that begins in Greece and moves on to Alexander and across Europe. He discusses the influence of each of the philosophers on the Roman world, medieval Christianity, into the renaissance, reformation, enlightenments and on into the 19th and 20th Century. He discusses how these two schools of thought shaped not only philosophy and religion, but physical and biological science, government, and economics. I compare reading this book to retaking the year of Western Civilization required in college when I was a student in the late 1970s.

However, the book does not read like a textbook. Herman often draws on illustrations from art and for popular culture to make a point. And a few times, his writing seems to become “creative” as when he writes as to draw us back into a particular situation such as Michelangelo’s stroll to the Sistine Chapel to paint, a cart rumbling down a cobbled road to the guillotine during the French Revolution, or Alexander von Humboldt encounter with a jaguar in the South American jungles.

Herman’s thesis is that for a society to do well, it needs the creative tension that comes from Platonic idealism and Aristotelian materialism. When one side is over-emphasized, bad things happen. Plato leads to tyranny and Aristotle to stagnation. But when the two are in competition, society flourishes. While Herman could be critical of Hegel, there is a certain Hegelian logic in his thesis.

I really enjoyed this book even though at times I felt he had to stretch things to keep everything lined up between Plato and Aristotle. I wish he had spent more time with Scottish Common-sense philosophy and with the work of Edmund Burke, but when you are trying to pack 2500 years into one volume, you can’t have everything.

This is the second book I read by Arthur Herman. Several years ago, I read and enjoyed How the Scots Built the Modern World.

###