Meeting the author

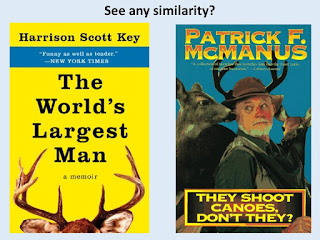

Roughly nine years ago, I attended a reading by a local author at the Book Lady’s Bookstore in Savannah, Georgia. I heard about the reading through Facebook. The book sounded interesting. At the appointed time, I left the slow life of the island for the hustle of the city and the struggle for parking places. Upon entering the bookstore, I was excited to see a stack of yellow paperbacks with deer antlers stacked by the register. “Hot dang,” I said to no one in particular, “Patrick McManus has a new book out.”

Then I saw the author’s name, Harrison Scott Key: the dude doing the reading… The air left my sails. Who was he? Key’s book utilized the same color scheme as had McManus. The antlers had me all excited..

Then the reading started. Harrison began by handing out PBRs. (That’s Pabst Blue Ribbon, in case you don’t know, the cheap beer from college days that’s now back in fashion). Harrison wasn’t taking any chances with his audience. Lubing us up, he soon had us laughing. By the time he was half way through the reading, I knew I would be buying his book. I thoroughly enjoyed it, pushing aside two other books that I was reading. His book was as good those written by McManus .

A few years later, I was at the party for Key’s second book reveal. It was held in the gardens at the Ships of the Seas museum in Savannah. He had definitely outgrown the “Book Lady Bookstore” as there were several hundred in attendance including Key’s three daughters. Not only did he sign my book, one of his daughters drew me a picture on the title page. Since I no longer live near Savannah, I was unable to be at his last book kickoff. It’s also his only book that’s not signed! Below, in addition to reviewing Key’s recent book, I included reviews of his first two books which I posted in earlier blogs.

Harrison Scott Key, How to Stay Married: The Most Insane Love Story Ever Told

(New York: Avid Reader Press, a division of Simon and Schuster, 2023), 307 pages, no images.

I finished the book a month ago and spent a lot of time thinking about it. How to Stay Married is an incredibly honest book. Key is honest about his desire to remain married despite his wife Lauren’s infidelity. He’s honest about mistakes he made. And he’s honest about his wife’s baggage. As for the latter, I might offer one more suggestion to Key, if he wants to stay married long-term, “Don’t write the book!” But it’s too late for that advice and Key has given us his story in a way that shows how messy our lives can be.

How to Stay Married can be very painful. It hits at places I’ve been in my life. It forced me to realize I haven’t always done everything, I should do to make the best out of relationships. Yet, the book is very funny. Key is a modern-day Mark Twain (and some of his insights into the Old Testament are very Twainesque). It’s an insightful book into human relationships, the church, scripture, and how our families influence our lives.

The Key’s move to Savannah when Harrison accepted a position at Savannah College of Art and Design. In time, they have three daughters, become active in Independent Presbyterian Church, and live in a quaint and comfortable home in a pleasant neighborhood. They become friends with neighbors and their children play with other kids. Unsuspectingly, Chad and Lauren have an affair. Chad is married and the father to some of the neighborhood kids. Both families have (or had) cookouts together. Key, who changes the names of key actors in the story, portrays this man in a comically plain manner. He wonders what his wife ever saw in such a boring ordinary person.

Lauren wants out. Harrison wants them to work on their marriage and fears what will happen to their children.

Harrison seeks help from the pastor of his church, whom he names “Hairshirt.” He tells him his situation, in the hope to learn how he offer suggestions to save his marriage. The pastor, not hearing Harrison’s plea, says his wife will have to confess and repent or be excommunication. This shocks Harrison, who imagines pitchforks being brought out. He wants to reconcile with his wife, not a witch trial. The pastor is from the Presbyterian Church in America, a very conservative branch of Presbyterianism. Harrison names him “Hairshirt” (think of those strict ascetic self-flagellating medieval monks). Afterwards, they leave the church and find a new church home. In addition to encourage the reader to fight for a marriage, the book could also be used as an example of how not to provide pastoral care.

While Harrison is estranged (at first just moving to separate rooms and later his wife moving to an apartment), he reads the Bible and provides interesting commentary on it. He spends time searching his and his wife’s past. His wife was from a broken home. Her father, also a Presbyterian Church in America pastor, abandoned his wife when Lauren was a child. Further turmoil came from their marriage. With Lauren’s mother dying of cancer, they move up their date in the hope she’d be able to be present. But she dies before the wedding. Their marriage begins in a rocky manner, but eventually things leveled out, or so he thought.

Later in the story, after Lauren moves out, she realizes what she’s throwing away. She calls Harrison, who rushes over to her apartment and packs up her stuff. They also find places Lauren can live to keep Chad from seeking her out. By the book’s end, Harrison and Lauren are slowly rebuilding their marriage.

As I said earlier, this is an insightful and extremely honest book. We see all sides of the main characters, good and bad. At times, I thought Harrison’s character was overly virtuous, but I had to admire the effort he made to save the covenant of his marriage. Thinking back 40 years, I wondered what would have happened had I been so determined. Harrison reminds us that marriage is often difficult and requires work. It would have been easy for him to have thrown in the towel and found someone else. While tempted, but he stood fasted and remained open for reconciliation because he loved his wife and wanted the best for his children.

I am glad I read this book and recommend it to others.

Harrison Scott Key, The World’s Largest Man: a memoir

(New York: Harper, 2015), 336 pages plus 15 bonus pages including an essay by the author on memoirs along with additional information about the author.

The World’s Largest Man is about Key’s father and his own quest to become a father. When Key was a child in elementary school, his father moved the family from Memphis, where you went to church to learn about the dangers of premarital sex). They moved to Mississipp

\i (where you went to church to engage in such sex). (19). According to Key, Mississippi is where crazy people believe what can’t be shot should be baptized (16), and children often learn child-birth before long division. (37) Here, Key was taught the ways of the woods.

One early adventure was dove hunting at daybreak in which he realized that problem with the proverb about the early rising bird getting the worm. They also get murdered. (32) Some readers may be offended by Key’s frankness concerning sex. In a few occasions he hints at the involvement of livestock. I wasn’t overly shocked as I once had a boss from Mississippi named Ron. One night after a few beers where he told us about a boy from his school… I’ve been through Mississippi, but Ron’s stories had always reminded me there was no need to linger. Key has reminded me again of the wisdom of passing through and keeping your windows rolled up.

Key keeps the humorous zingers coming as he tells about deer hunting, fighting at school, his first love, football and baseball. He also shares about his father’s tough discipline and his mother’s love. At times, as the reader, I felt contempt for his father. And then, at other times, I couldn’t help but admire him. Key’s old man went out of his way to help children. He continued coaching little league baseball and football long after his boys had grown up and moved on. Key always felt he was not living up to his father’s standards (something most boys feel, or at least I did).

After high school, there is a gap and Key picks up his story when he is in grad school and is married. He worries what his new bride will think of his family and there are some funny episodes around her first visits to Mississippi for holidays. Once they have children, he sees another side of his father. His old man loves grandchildren. Eventually, Key is able to encourage his parents to move to Savannah where he is a professor at SCAD (Savannah College of Art and Design). A month later, his father dies of a heart attack.

In the second part of the book, we see Key’s struggling to be a man and protecting his wife and three daughters. Having grown up around guns, he marries a woman who wasn’t a “gun person. He leaves his guns with his parents. One night, he arms himself with a serrated kitchen knife to check out a possible bad guy. As Key says, “it would have come in handy had he come across an angry Bundt cake.” (273) After his father drops off his old shotgun and they experience a break-in, he obtains shells for the shotgun. But then, he realizes it was a foolish idea, He adds motion sensor lights outside of his house and an alarm system.

The last part of the book may not carry the humor of the earlier part of the book, but it has an honest feel as Key struggles to learn what it means to be good husband and a good father. There is a tenderness to how he writes about his family and his aging father. Key recalls the old truism from the country that things can kill you can also make you feel alive (238), but a few pages later he acknowledges that what really makes us alive is love. (246). This is a book written in love, which is why I recommend it. McManus has some good competition as does other Mississippi writers such as Willie Morris.

I also liked the supplemental information provided at the end of the book. These include tips about writing about one’s family, an essay on memoirs (a term Key detests), more biographical information, and his top ten list of funny writers of which I’ve only read four (Charles Portis, Douglas Adams, Flannery O’Connor and Mark Twain). Key acknowledge at the front of the book that he had changed many of the names (since most of them have guns).

Harrison Scott Key, Congratulations, Who Are You Again? A Memoir

(New York: Harpers, 2018) , 347 pages including five appendices and no illustrations except an ink figure of a dog drawn by Beetle, the author’s daughter, while I waited for him to sign my book.

Over the years I have enjoyed reading memoirs by authors as I learn how they approach the craft and gleam advice for myself. Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life, Eudora Welty,’s One’s Writer’s Beginning, Robert Laxalt’s, Travels with My Royal: A Memoir of the Writing Life, and Dee Brown’s When the Century was Young are books that come to mind.

I’ve also read many “how-to” books by authors who tell us how to approach the craft. Without looking at my shelf, I can recall Stephen King, “On Writing; William Zinsser, On Writing Well; Ray Bradbury, Zen and the Art of Writing; and John McPhee, Draft #4. All these authors of memoirs and how-to books have an impressive list of publications under their belt when they sat down to give advice on writing. Harrison Scott Key decided he’d write his how-to memoir immediately following the publication of his first book. But then, his first book won the Thurber Prize.

I enjoyed reading Congratulations, Who Are You Again? even though I am not sure I would have called this a memoir. I’m not sure what it is.

Part of the book reads like a “how-to” manual for becoming famous and having a best seller. Another part of the book is the author’s quest to find discover his life’s purpose as he charges through much of his 20s and 30s like Don Quixote. Part of this books appears to be a sure-fire way to receive a summons to divorce court. Another part of this book is Mr. Key’s depository for lists. And just in case you didn’t have your fill of lists within the text, Key fills his appendices with lists. What is it about all these lists? I was wondering why he didn’t include a grocery list, but concluded that maybe his wife, out of gratitude for now having more than one toilet in the house, has volunteered to shop for the family.

My hunch is that Mr Key’s lists are actually passwords. What a better way to keep them close at hand than to have a book he can pull off his shelf and quickly recall his password for Facebook or Twitter or maybe even First Chatham Bank. And, one final “what is it…” What is it about depressed people and pelicans? Key speaks of his interest in these “freakish and ungainly” birds while depressed. Personally, I find pelicans graceful. A former professor of mine, Donald McCullough, while dealing with depression, published a book titled The Wisdom of Pelicans. Like my former professor, I find pelicans graceful, not freakish. I’m not sure what’s wrong with Mr. Key. Maybe I should give up watching pelican’s fish, but that sounds too depressing.

That said, this is a funny book. And writing a funny book is one of Mr. Key’s life goals. He’s now achieved this goal twice, first with The World’s Largest Man, and now with Congratulations. Although Key acknowledges his indebtedness to a host of authors, he never mentioned the fabulous 1940 movie, “Sullivan’s Travels,” staring Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake. In “Sullivan’s Travels,” McCrea plays a movie producer who wants to make a movie about the seriousness of the Great Depression in order to move people to respond in compassion. But after a misfortune, he has an epiphany and realizes people also need to laugh. Sullivan learns this wisdom after at the end of the film. Key comes this conclusion on page 49.

My third complaint about Key’s writing (my first complaint was his lists, my second was his rude remarks about pelicans) is his overuse of misdirects. Key describes the great things that follow his things such as being published. Following such good news, Key rambles on about all the invitations to TV and radio shows to make an appearance. He seems to have a healthy crush on NPR’s Terry Gross. Others ask him to give keynote speeches. He’s also mugged by admirers on Savannah’s streets.

Just when the reader is about to believe there is a god who awards hard work, the reader is redirected into what really happened. Usually nothing. The exception is an actual mugging on Savannah’s streets. Actually, Key never wrote about being mugged, but it could happen. These redirects were funny the first 57 times this reader fell for this comic technique, but the 58th time was just too much. As I was coming to the end of the book, I thought that if there was one more redirect, I’d rip the book apart and toss it out the window. Thankfully, being near the end, I was reading lists and it’s pretty hard to redirect a reader from a grocery to a household chore list. I never knew lists could be funny.

Complaints aside, I thoroughly enjoyed this book and laughed a lot. My biggest take-away from Mr. Key is that writing is like giving birth. I’ve heard that before, but Key attaches his unique twist that refreshes this platitude: “Writing is like giving birth, and it is, it is just like giving birth, in the Middle Ages, when all the babies died.” (114). Writing is hard work, and such hard work in this case produces a book that the reader can easily read and enjoy.

And one final comment for clarification. I am not the minister who accosted Keys in a restaurant asking to be included in his next book. Such a request is foolish for if Keys says the things he does about his wife and children, whom he obviously adores, what would he say about a coveting minister. Of course, the minister did find himself in the book, only he’s not identified.